What Benton Harbor Needed Was Elliot Uzelac

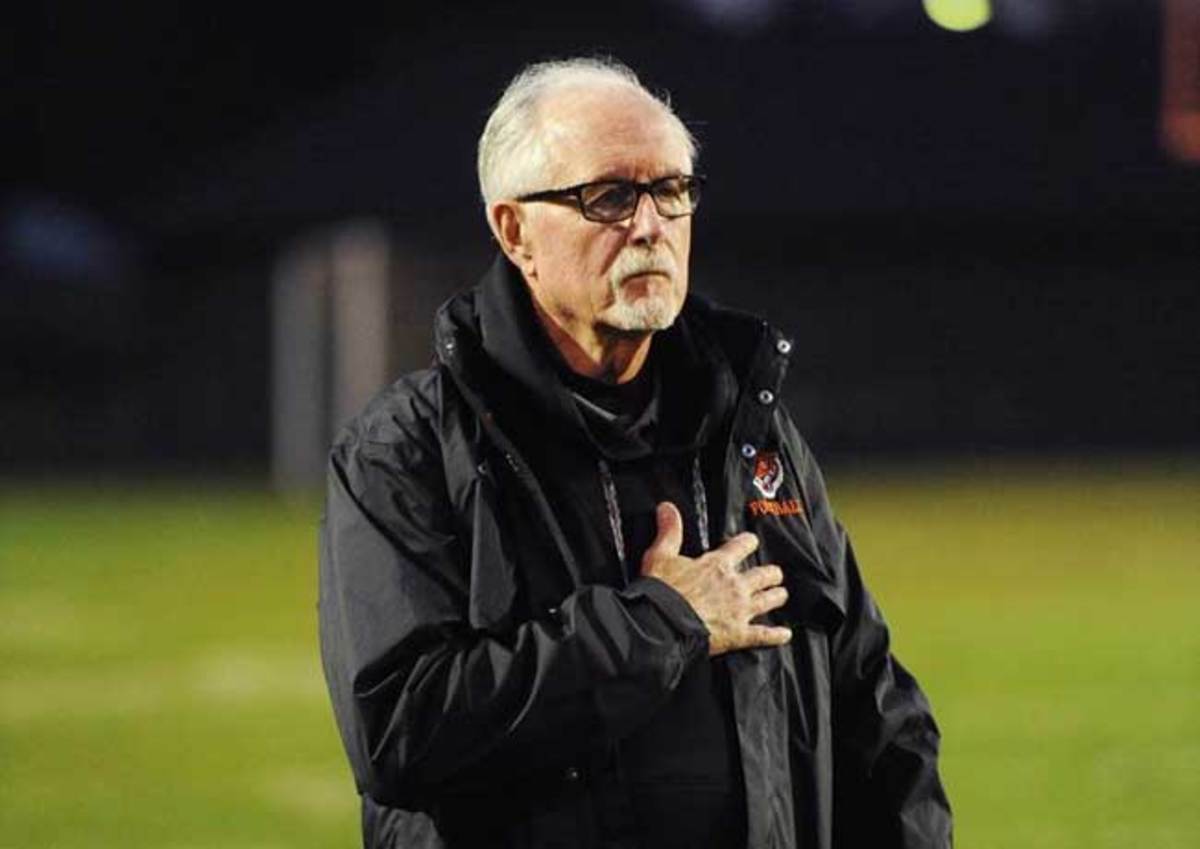

BENTON HARBOR, Mich. — Elliot Uzelac took over this moribund football program at a struggling school in a worse-off town with clear goals. The boys would pass their classes. They would commit their weekday afternoons to practice. And they would make the playoffs. He even wrote that word—playoffs—on a chalkboard during his first team meeting, underlining it three times for emphasis. Never mind the fact this team had won four games in eight years.

Incredulous, a few players pulled out their smartphones and Googled this crazy man with white hair and a gruff voice. Before them stood a football lifer who had once coached under Bo Schembechler and Bill Belichick, a 74-year-old who had once been the head coach of Division I college programs.

After mapping out the team’s future, Uzelac met with each player individually. Most were concerned about their after-school jobs, which in the past had prevented them from attending practices. Some were their family’s breadwinners, which shocked the coach. With the help of a school board member, Uzelac arranged job alternatives and reinforced his expectations for being a member of the team. Ruth Harvey, a longtime equipment manager, was a fly on the wall for most of these meetings and heard one boy tell his new coach, “Don’t worry, I’m quitting this job, because I believe in you. I want to change my life.”

Harvey left the room, went to her car in the cracked-earth parking lot and wept into her hands. “That man is here for a reason,” she says of Uzelac, who politely declined the salary that accompanied the least desirable coaching job in the state of Michigan. “He was sent here. God has truly blessed us.”

It’s a feeling that has spread throughout this tiny outpost on the shore of Lake Michigan—and not just because the Tigers had their first winning season in 25 years and earned their first playoff berth in school history.

* * *

Elliot Uzelac wants the story of the 2015 Benton Harbor Tigers to be about the kids, not their coach. But without him there never would have been about 2,500 people cramming into an underused high school stadium last Friday night to watch the Tigers win their first playoff game in school history, a 28-7 victory over Dowagiac High.

Before Uzelac’s arrival, the team had endured two consecutive 0-9 seasons and gone through five head coaches in three years. “You had teammates fighting each other or yelling at the coaches after mistakes on the field,” says Percy Brown, a junior fullback.

Uzelac grew up in Gary, Ind., and played college football at Western Michigan in the early 1960s, about an hour’s drive east of Benton Harbor. Every autumn from 1965 to 2010, he coached football somewhere in America. He worked as an assistant for Bill Belichick’s Browns; he was the head coach at Western Michigan and Navy; he was the offensive coordinator at Bowling Green, Ohio State, Colorado, Kentucky, Minnesota and Georgetown; he worked as an assistant at Indiana, Maryland and Michigan, where he grew close with Schembechler, adopting his practice structure and motivation methods for struggling students.

“He was almost like a father to me,” Uzelac of Schembechler.

Uzelac was no stranger to the local football scene, either. From 2006 to 2010 he coached at St. Joseph High, in the town across the river from Benton Harbor. He stepped down in 2011 to spend more time with his grandchildren.

Two years into his retirement, Uzelac underwent a cardiac ablation procedure to correct a problem with his heart’s rhythm. (He’d had open-heart surgery when he was a 50-year-old assistant at Ohio State.) By January 2015 he was at full strength, and his wife, Wendy, noticed how bored he’d become just hanging around the house. So last winter, as they drove from Michigan to visit family in Alabama, Wendy floated the idea of getting back into coaching, wondering aloud if her husband might make an impact at the school across the river from St. Joseph, where they lived.

Uzelac, of course, was familiar with Benton Harbor as an opposing coach. He remembers scouting an away game in 2007, some two hours away from the school, and seeing only six fans on the Tigers’ side of the field. He always had a soft spot for Benton Harbor and would instruct his offense to hold back after securing a safe lead.

As he and Wendy kept driving south, Uzelac kept thinking about his hometown in Indiana, about when it was thriving, and about its decline when industry dissipated and crime rose. The story of Gary, Indiana, he realized, was also the story of Benton Harbor.

“The big question my wife and I talked about was, Why would we want to do this?” Uzelac says. “This community has been in hard times in every way possible, and that’s why we’re here. Because I know if I can start turning young men around, and they do better, then they can come back and help the community do better.

“I called the athletic director, and he said they had an opening.”

* * *

There have been unforeseen challenges, and conversations the coach never imagined having.

On Oct. 25, two days after the Tigers improved to 5-4 and secured a trip to the playoffs with an overtime victory over Portage Northern, police responded to a shooting in broad daylight outside the Blossom Acres Apartments. Karlos Kelly, a 17-year-old junior at Benton Harbor High, had died at the scene from a shotgun blast to the chest.

Security footage from the HUD-funded complex of humble two-story homes confirmed what witnesses had recounted: that three teens—later identified as 18-year-olds Daquantaries “Quan” Williams, Seddrick Williams and Anthony Walker—allegedly drove into the gated complex and put on orange ski masks. They engaged Kelly in conversation before one of them exited the car and shot him. Police have not disclosed a possible motive.

Kelly was known to all of the boys on Benton Harbor’s football team, having played with them in middle school. He was also the cousin of several players. What was supposed to be a Sunday spent watching Michigan’s playoff selection show on television was instead spent in mourning.

Brown, the junior fullback, learned of the shooting on Facebook and visited the scene an hour later. There was already a crowd gathered around the spot where the body had fallen—and where a teddy bear, flowers, candles, and empty bottles of Grey Goose, Courvoisier and Remy Martin would be left as a memorial.

“I saw some of my closest friends crying,” Brown says. “A couple people were mad and ready to avenge.”

Jeremy Burrell, a junior tailback, was Kelly’s cousin on his mother’s side. He stopped hanging out with Kelly and his crew after middle school, he says, “because they were always on a different page.” But that night, Burrell and his mother, Tamala Davis, visited with Kelly’s family and watched the evening news in silence.

“They were in the streets,” Burrell says of Kelly and his cousin’s cohort. “They’d come to school sometimes but get suspended a lot. When we beat Portage Northern, he rushed the field with the rest of the students. He said, ‘Hey Cuz, look out for me next year. I’m coming out to play.’ I believed him, kind of. A lot of his friends I used to hang with kept on saying that.”

The day after Kelly died, Benton Harbor principal Reinaldo Tripplett brought in grief counselors. Uzelac still hosted his daily sixth-period film session with the entire team—a new addition to the class schedule, which the coach had insisted upon—but first addressed the tragedy.

“This is a black community, and you’re young black men,” he told them. “You have a lot of obstacles, and you have to learn to say no. You have to learn to keep yourself out of bad situations. Ask yourself this question: Do you want to be dead a year from now because you made one wrong decision?”

That the players hung on his every word showed how close this team had become.

The group of coaches Uzelac assembled, some of them former players at St. Joseph High, had never met teenagers who were so closed off. Coaching was often mistaken for criticism, and players often responded with indifference, backlash, or some combination of both. “They just didn’t trust people because they’ve been treated so poorly,” says Kris Hickman, who directs the scout team.

During the first game of the season, one of the team’s hardest hitters, a 220-pound middle linebacker, snapped at a coach who tried to correct a botched assignment. Says Brown: “Coach brought it up the next day and said, ‘Look around. Someone isn’t here. If he’s not trying to accept coaching, there’s no reason for him to be here.’ ”

Soon after, Uzelac asked the starting quarterback—perhaps the best athlete in the school—to hand in his equipment after missing numerous practices without an excuse. Though he couldn’t play because of an injury, he was still expected to show up just like everyone else.

“We couldn’t have that kind of atmosphere,” says defensive coordinator Jerry Diorio, who played for Uzelac at Michigan and went on to a successful high school coaching career. “We needed to raise the bar. We needed to get them to do the things we knew they were capable of doing.”

After the Tigers won their first game in three seasons, a Week 2 victory over Central High of Battle Creek, several students tried to join the team. But they hadn’t put in the work, and Uzelac thought a scenario in which a late addition supplanted an original member of the starting lineup would send the wrong message. Still, Uzelac had his doubts about turning some boys away and kicking others off the team.

“Coach U sometimes feels bad because he doesn’t seem to think he can reach enough of these young men,” Diorio says. “But he’s wrong. He’s reaching more people than he knows.”

* * *

In 1862, fruit growers from Berrien County sought an easier path to Lake Michigan without having to rely upon business relationships with St. Joseph. So they cut a canal leading to a new village outside St. Joseph’s city limits, which drained the previously inhibiting marshlands. Benton Harbor became a major hub in the Midwestern fruit trade, and later, an auto-manufacturing stronghold. Population peaked at 19,136 in the 1960 U.S. census.

Three years later, in July 1963, Illinois congressman Barratt O’Hara, who was born in Berrien County in 1882, pulled from his office wall a framed photo of the 1899 Benton Harbor High School football team featuring several African-American players. He stood before the U.S. House of Representatives during integration talks and told the story behind the photo, according to the Benton Harbor News Palladium, “to emphasize the point that color was no issue or bar to football players on the team of which he was a member.”

In 1966, Benton Harbor was besieged by riots in response to the fatal shooting of an African-American by a white man. The National Guard was dispatched, as the Chicago Tribune put it, to quell “a crowd of negro youths.” The riots, coupled with the decline of the auto industry, initiated the flow of white families moving from Benton Harbor to St. Joseph.

“St. Joseph served as a convenient jump-over to a better school district,” says John Armstrong, a local historian, architect and author whose family was a part of the white exodus from Benton Harbor. “The riots freaked people out. My parents said we moved because of the crime. I heard people talking about crime and theft, but I never saw it. That was a catalyst, real or imagined.”

Simmering racial tensions came to a head in May 1991, when the body of Eric McGinnis, a 16-year-old African-American from Benton Harbor, was found in the St. Joseph River, which separates the two towns. The dubious circumstances surrounding his death are the subject of a book by bestselling author Alex Kotlowitz, The Other Side of the River, which contextualizes the relationship between Benton Harbor and St. Joseph as microcosm of de facto segregation in America. In 2003, after two more black men died during attempted police apprehensions in Benton Harbor, the city again erupted in violence and looting. Twelve years later, 84% of the current police force is white, according to Marcus Muhammad, a candidate for mayor and the restorative justice manager at the high school.

Few, if any, of the football players at Benton Harbor High know the story of Eric McGinnis; The Other Side of the River isn’t exactly required reading in English class. The extent of their knowledge of a racial divide comes from warnings handed down from parents and older siblings. Says Brown: “People say, If you go across the bridge, you’ll end up in the St. Joe River. I don’t buy into it.”

The players’ weekly forays to the Buffalo Wild Wings in St. Joseph go on without incident, but the contrast between the two river communities is impossible to ignore. Benton Harbor is nearly 90% black, with a median household income around $17,000; St. Joseph is nearly 90% white, with a median household income around $50,000.

“We are one of the poorest cities in state of Michigan, with the highest rate of convicted felons and the highest foreclosure rate,” Muhammad says. “The average family here survives on about $200 a week.”

Almost a decade ago, Michigan introduced the Schools of Choice policy, which effectively allows students to apply for public schooling in districts where they don’t live. It was devastating for Benton Harbor: eight years ago there were about 1,500 students enrolled, now there are about 600.

The process for transferring isn’t as simple as opting in or out of the district. Students must apply to other schools, which often turn down applicants based on behavioral histories. Over the past five years Benton Harbor has academically performed in the bottom 5% of Michigan public schools. Its football players regularly face former middle school classmates now on opposing teams.

Uzelac knew all of this when he offered to take the Benton Harbor job last winter, a hiring that wasn’t made official until July 21 because of an undisclosed police investigation into the superintendent. By then, most high school coaches across the country had begun offseason workouts with returning players. After his hiring, the nearby teen center, which once served as the school’s athletic complex but had fallen into disrepair, underwent a makeover in a matter of weeks. Friends of Uzelac’s from across the river lined up with discounts or flat-out donations of services and supplies—new lockers for the varsity team; new equipment for the weight room; furniture and carpeting for the coaches’ office. In the past, such help has been rare, though Benton Harbor alum Joique Bell, the Detroit Lions back, hosts a summer footbal camp in the town and donates cleats to the team.

“Coach Uzelac will not talk about this, but he has a unique way of being able to pull resources together,” says Maurice Burton, a Michigan state trooper and a 1976 graduate of Benton Harbor. “He’s been around a long time, and he was able to get some of the fundamental things the kids needed to compete.”

* * *

At the beginning of the season, Percy Brown saw the writing on the wall, so he started writing in the team’s Facebook chat. There were about 40 boys still on the team after the coaches asked the quarterback and middle linebacker to leave, and the guys still weren’t quite getting it. They lamented the two departures in a group chat that has helped chronicle the season. (Many of the boys don’t own cell phones, so Facebook is one of the few practical ways to communicate.)

“If the coach is just yelling at y’all,” Brown wrote, “say ‘Alright, yes coach,’ because he’s going to make us run or you’re going to be cut.”

This was new territory. Before 2015, adversarial player-coach relationships were the norm. Some players skipped practices but kept their starting jobs. Others showed up to practice, but would sit and watch with their helmets off if they felt like it.

“I’m not gonna lie—I used to be sitting down and watching practice,” Brown says. “And I was the starting running back.”

Before Uzelac took over, players needed to maintain only the county requisite GPA in order to play. Now they have bi-weekly grade assessments that must be filled out by teachers; struggling students also have access to tutors.

Brown and Burrell, junior running backs, are two of the players who’ve made big improvements.

“When the school year started they all wanted A’s,” says Dustin Slivensky, an English teacher. “I’m like, Are you sick? They were the squirrely kids in ninth grade, 10th grade, so I’m thinking, Who are these children? I’ve just seen such a huge turnaround with the players in every aspect. They don’t get caught in the hallway without a pass. The guys who were involved with the drama with girlfriends last year now say, ‘We don’t have time for this anymore.’ ”

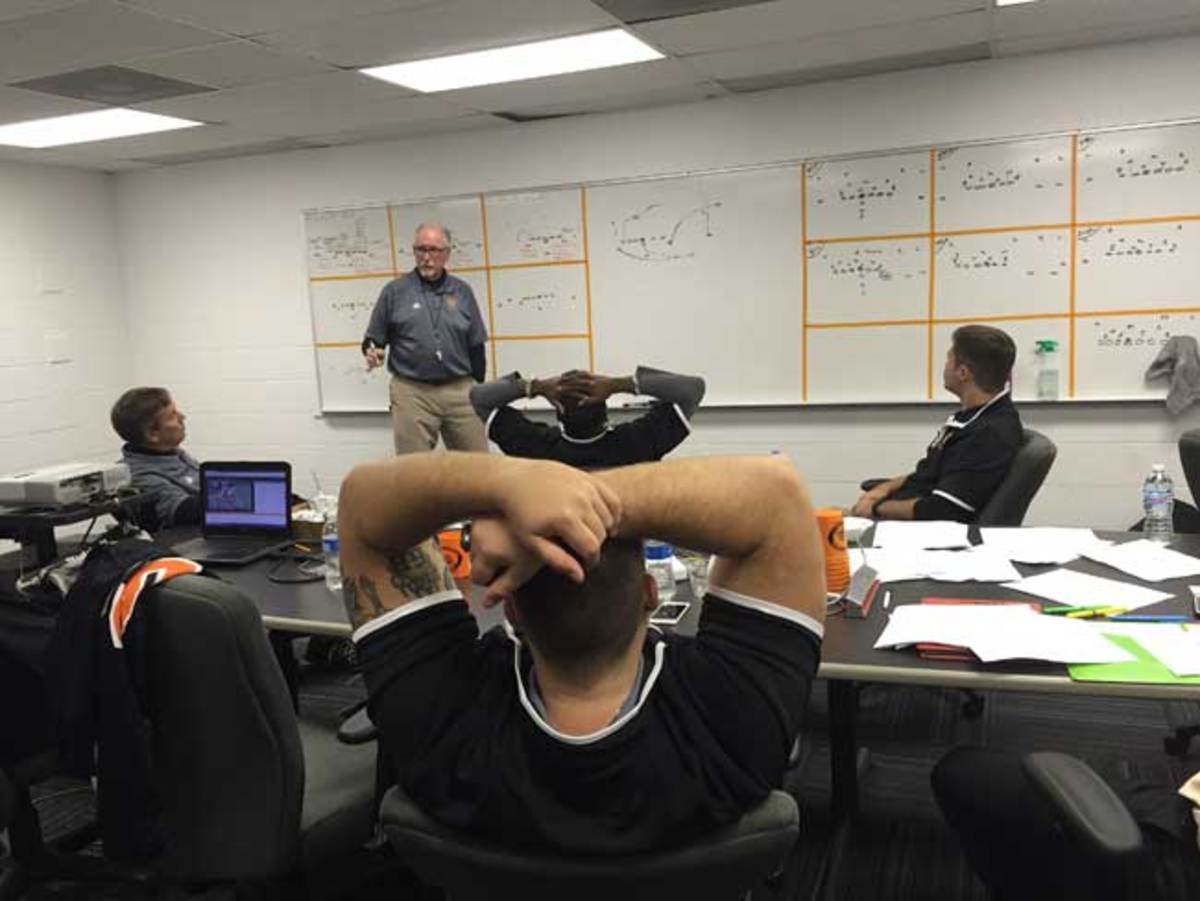

Football itself has become a class, a way of teaching players how to study. Uzelac, defensive coordinator Diorio, offensive line coach Matt Mattox and defensive backs coach Devonte Jones lead hour-long sessions during sixth period. The Tigers study the upcoming opponent and correct their own mistakes. Uzelac highlights alignments and tendencies on the game film with a laser pointer, occasionally deviating from the script to point out his nine-year old grandson Charlie celebrating touchdowns by awkwardly jumping up and down. “See,” Uzelac will say, “white men can’t jump!”

Last Thursday’s film session focused on Dowagiac, the Tigers’ first-round playoff opponent. Burrell, the team’s leading rusher with nearly 1,000 yards, didn’t practice with a strained quad—an injury that put the status of the running game in limbo.

Though Brown and Burrell are indistinguishable from certain angles, given their nearly identical fade haircuts and chiseled 6-0 frames, they’re different types of backs. Burrell has the extra gear and agility necessary to get around corners; Brown thrives between the guards, delivers punishing blows and almost always falls forward. But the difference between the two was far from Uzelac’s chief concern.

The win over Portage Northern to earn a playoff berth had brought the football team regional and national media attention. Television cameras filmed their every move at practice, and there would be a pep rally on Friday afternoon before the night’s game. That last bit of news set off an alarm for Uzelac.

As an assistant on Bill Belichick’s 1992 Cleveland Browns staff, Uzelac made it a mission to absorb the young head coach’s philosophy and practices. “You knew he was going to have the success he would eventually have,” says Uzelac, who also coached with Belichick’s father, Steve, at Navy. “There was no stone unturned. Every single thing was handled in great detail. And he hated distractions.”

Channeling Bill Belichick, Uzelac wrapped Thursday’s practice with a warning.

“We’re grateful and blessed to have the media here,” he said. “But you have to act like you’ve been here before. What’s important to you is tomorrow night, playing like you’re capable of playing and winning this game.

“I don’t care if we have a pep rally, we’re not going. You know me—you know I ain’t going to no damn pep rally.”

* * *

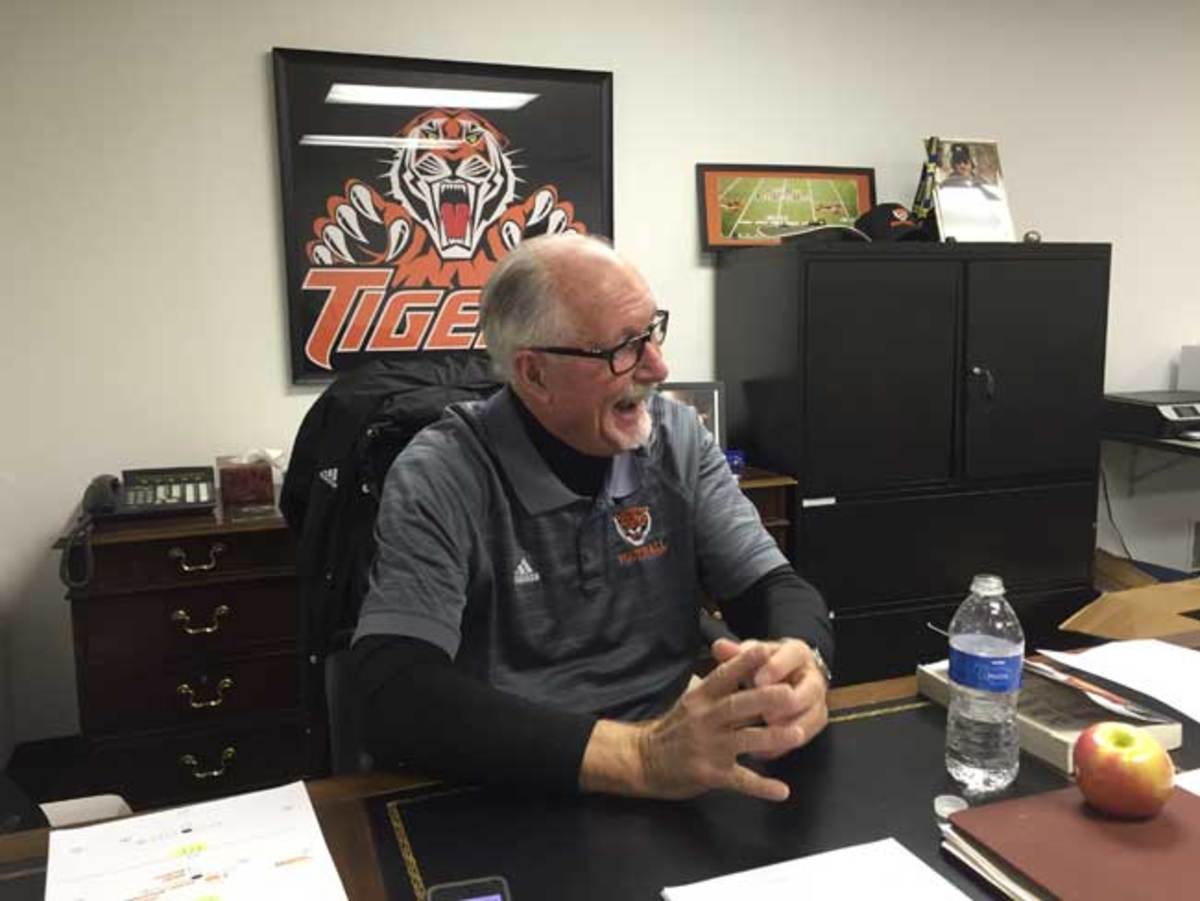

On Friday afternoon, a local doctor clears Jeremy Burrell to play, which the coaches find out as they’re discussing last-minute tweaks to the game plan in an office outfitted with a desk for the head coach, a conference table and a large whiteboard covered with play diagrams.

It occurs to someone that Dowagiac could run the halfback-toss pass it has showed twice this season. Four Benton Harbor defensive coaches bat around ideas for preparing for it, but Uzelac has the final word. “It won’t be a big play, but they’ll gain some yards,” he says. “That ’backer has to cover it. That’s the only way. Now let me get some sleep.”

Uzelac then props his feet up on the desk and leans back toward an autographed portrait of Bo Schembechler, his former boss at Michigan. Thirty seconds later, a thought stirs him awake: “Tell me who you’ve got playing Tiger again.”

In another room, Burrell finds it hard to sit still. He’s excited to be playing, but has a lot on his mind: his deceased cousin; his father, Jeremy Burrell Sr., who is serving a 32-year sentence at Baraga Correctional Facility for an attempted murder in 2007; his mother, Tamala Davis, who is working a training shift tonight at a local eatery and might not be able to leave in time to make the game.

Davis gave birth to Jeremy as a high school sophomore and was kicked out of school a year later for fighting. She spent the next decade in an out of jail for similar offenses. In November 2014 she was sentenced to 60 days in jail—through the holiday season—after an altercation in which she says a gun was pulled on her. Her children told her she was a different person when she was drinking. “I’d never been away from my kids for a holiday,” she says. “The things that my kids told me, they’ll make any parent change.”

At 5 p.m., the team puts on brand-new all-black Adidas uniforms and gathers in the locker room for a pregame speech pumped with emotion.

“We’re gonna be more physical than they think they are,” Uzelac says. “That’s number one. Number two: mental errors. Don’t make mental errors. Number three: No turnovers. Number four: No penalties. Be smart. I don’t care what happens on that field—you don’t retaliate. Be smart. Ya got me?”

Yes sir!

“Play with Tiger pride,” he continues. “Play like you have played when we beat teams who everybody said we couldn’t beat—and everybody is saying the same damn thing again. You will beat this damn team if you play with pride and the four things I just talked about. You understand me?”

Yes sir!

“It’s our ride. They’re in the way. Don’t let them stop the ride.”

Yes sir!

“Let’s go out there and kick some ass.”

There is a moment of silence for Karlos Kelly, the murdered student, before the opening kickoff. Then Benton Harbor launches a clinic on how to execute the spread running game. Burrell and Brown alternately take handoffs from junior quarterback Tim Bell for big chunks, until Brown powers into the end zone from four yards out to open the scoring. Late in the first half, Dowagiac muffs a punt that is recovered by junior receiver JuQuan Bennett, leading to a 20-yard touchdown pass by Bell that puts the Tigers up 14-0.

In the stands, boosters hawk $1 programs, exclaiming, “Buy a piece of history!” Former players who’ve graduated can be overheard reminiscing about the success they would have had under Uzelac. Yet at the same time, principal Reinaldo Tripplett is dismayed to hear pockets of resentment for all the attention a white coach is receiving for turning around the football program. “I don’t care what color he is,” Tripplett says. “We are blessed.”

Late in the third quarter, Dowagiac gets desperate. Down by two touchdowns, the Chieftains attempt a dive up the middle on fourth-and-1 and fail to convert, with Brown playing a lead role in the defensive surge.

Still dressed in her work uniform, Tamala Davis arrives in time to watch the fourth quarter and see the Tigers close out their 28-7 win in victory formation. Burrell and Brown combined for 210 yards. And Dowagiac did in fact try that halfback-toss pass, but the defensive end snuffed it before the runner could get the throw off.

A day later, the coaches are in the teen center to watch the game film with players and begin preparing for undefeated Zeeland West in the district title game. Win or lose, Uzelac vows to return next season. There will be more kids coming out for the team, more tutors to help them study, and better football at Benton Harbor. It won’t be boring, and at least one life has already been changed for the better.

“Honestly, they’ve given me more than I have given them,” Uzelac says of his players. “I’ve never had more fun working with a group of young men than I am right now.”