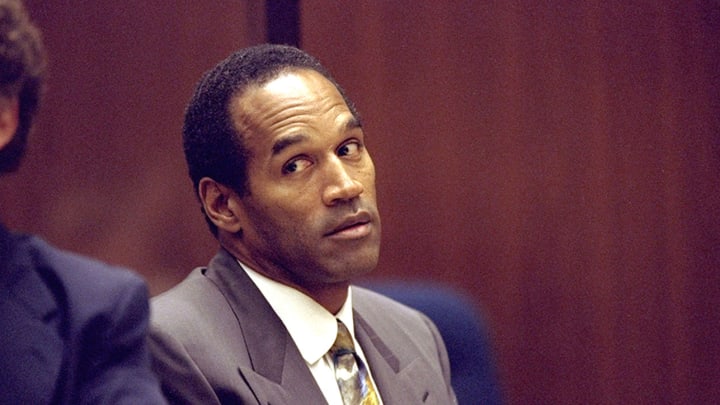

How Far Have We Really Come From O.J.?

Ezra Edelman’s five-part documentary that aired on ESPN last week, O.J.: Made in America, is remarkable as a case study in myriad issues, including but not limited to race, poverty and criminal justice. But what jumped out to me was one particular interview with Simpson filmed several years before his wife Nicole Brown’s murder, and what it says about the athletes we think we know.

In 1989 Roy Firestone, host of ESPN’s long-running interview program Up Close, landed a sitdown with a retired Simpson following an alleged incident of domestic violence on Simpson’s part that had made news. Those watching at the time might have wondered how hard Firestone would hit Simpson on the allegations (for which no arrest was made). They didn’t have to wait long to find out. “When you live your life so publicly, and really almost with such ease, it’s hard to believe that there could ever be any rocky time,” Firestone says, his face growing into an expression of concern. “The reason I’m bringing that to light now is not dredge it up again, but more or less to talk about how things can get distorted to such a point that you are portrayed as a bad guy.”

The rest of the interview, and much of the documentary as a whole, illustrates a single, important theme surrounding Simpson and his history of violence: No one knew. Or at least, no one wanted to know. Not his closest friends who doted on him, nor the media contingent that followed him. Certainly the general public who adored him had no idea that Simpson had been regularly battering his wife up until her murder. Only those closest to Brown had any inkling. O.J. was among the most visible celebrities of the day—no black man before had accomplished half as much in the field of television and film following a pro football career—and he was loved.

Here's the obvious next question: Could it happen now? In the age of social media, when faults are laid bare and reputations routinely damaged by a stranger’s smartphone or a grainy surveillance video, could we all be still duped by a talented athlete, grinning pitchman and congenial actor? Simpson had the benefit of a sports media that put a premium on discretion and lacked the capacity or necessity for urgency. As a result, he was able to lead a highly scripted life in the press, and he took full advantage, because he understood the power of personality in sports well before technology caught up with demand. “The public has to identify with the athlete,” Simpson said during his playing career, in another interview excerpted in the documentary. “You can be in awe of the athlete, but you want to feel a part of that person.”

This is the basis of much of popular sports journalism: the desire to go beyond the player and be in touch with the person. But that often comes with a willing suspension of disbelief. Writers and television producers spend hours, days or even weeks with an athlete for stories that endeavor to summate a life. We cling to narratives and hold back suspicion; we want to get up close andpersonal. Sports Illustrated all but invented this type of athletic coverage, and in its archives from the 1990s and early 2000s you’ll find glowing celebrations of Mark McGuire and Sammy Sosa, Lance Armstrong and Marion Jones and Alex Rodriguez, that look naïve in hindsight.

So what’s changed?

For starters, today we feel closer to our athletes than we ever have been, and perhaps than we ever wanted to be. Women snapchat selfies alongside sleeping NFL players after sexual conquests; Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat give us endless seemingly unfiltered glimpses into the daily lives of players; and athletes are caught battering women on incontrovertible video. Journalists who soft-pedal athletes’ faults or aid in celebrity redemption tours face harsh and immediate backlash from a community of readers wielding a louder voice than ever before. The veil of old media that shielded the real Simpson from the world is gone, right?

Well, not exactly. Not if you watched or read recent coverage of Floyd Mayweather or Greg Hardy. Too often we speak about such athletes as though they’re fighting back from some adversity or hardship, ignoring the pain they’ve been alleged to have inflicted on others. But it’s not hard to understand the reporter empathetic to superstar athletes if you’ve spent any time with the athletes. Many of them are capable of the sort of charisma Simpson was known for. In interviews last week, Firestone said he’d been “conned” by Simpson the way everybody else had. Said one journalist interviewed for the doc, who profiled Simpson: “Being O.J.’d is the confusion that you feel after you’ve been in his presence. I don’t think he was not guilty, but I was in touch with the fact that I wanted to think he was not guilty.”

ESPN’s Adam Schefter, after interviewing the often gregarious and charming Hardy following accusations of domestic violence, told The Dan Patrick Show, “I found him to be a changed kind of guy.” Schefter later said he regretted the comment. His colleague Michelle Beadle slammed her own network for being a vessel for Hardy’s redemption story.

At issue is a machinery surrounding pro athletes that often prejudices those of us who sit on the fringes from thinking objectively. We like football, and we like to see the best football players on the field, so the natural (and dangerous) inclination is to forgive off-field faults. Stephen A. Smith defended this point of view in April 2015 when discussing his own buddy-buddy coverage of Mayweather, a convicted domestic abuser: “Once the court of law has dealt with them, in whatever way they choose, we ultimately get back to why they are relevant in the first place. They are relevant because as fighters they are great and people want to see them.”

Yes, technology has evolved, but the circle of people shielding athletes’ true identities has expanded, and access is at an all-time low.

Beyond that, there’s a great deal of money to be made for a great many people when athletes like Hardy and Mayweather are deemed worthy of forgiveness. Just ask Denise White, founder of sports representation firm EAG Management, who has gained fame for being a crisis manager for athletes. White’s small army of representatives regularly exchange access to athletes with reporters for well-defined parameters about what can and can’t be asked of her clients in interviews. An upcoming movie about her life and work starring Jennifer Aniston is titled The Fixer.

Many agencies that represent athletes in contract negotiations also hire social media gurus who monitor their players’ posts and delete them at will, sometimes successfully before the backlash to an ill-advised post kicks in. Yes, technology has evolved and new platforms have emerged, but the distance between the athlete and the public has not narrowed, because the circle of people shielding their true identities has expanded, and true, unfettered access is at an all-time low.

• MORE OPINION: Klemko on why early retirements aren’t a threat to football

If you wanted to talk to Washington third-string quarterback Robert Griffin III last year, you had to get around a team media relations assistant barking “No interviews.” When I traveled across the southeast last year reporting on the 20-year-old locker-room incident between Peyton Manning and University of Tennessee trainer Jamie Naughright, it was Ari Fleischer—former press secretary for President George W. Bush—who served as gatekeeper for all communication with the Mannings. Another former White House press secretary, Joe Lockhart, went from the halls of power under President Bill Clinton to the office down the hall from NFL commissioner Roger Goodell in 2016, to help deal with the numerous crises dogging the league at any given moment. And few in the industry would call Fleischer’s and Lockhart’s postings a step down. That’s how big the stakes are in sports today, and how important the management of the image and the message has become.

These layers upon layers of Teflon, and our inability or unwillingness as an industry to penetrate them, help shield athletes and sports leaders—guilty and not guilty—from facing accusations in an open forum. And occasionally the protective bubble marginalizes and suppresses victims of all kinds.

Two decades after Simpson’s fall from grace we’re forced to ask ourselves once again: How much do we really know?

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.