A Bully Comes to Town

The Delicate Moron returns after a two-week hiatus because of NFL free agency and the start of March Madness…

Part 1: A Man, the Arena, and His First KISS of Fate

Part 2:A Quixotic Bit of Foolery

Part 3:Judgment Play

Part 4: ‘A Very Attractive Man of Great Sexual Power’

Part 5:Arena Dreams: In Search of 26 Riders

Part 6:As a Realist, You Should Know Anything Can Happen

PART 7

April 5, 2016

It was the kind of win the KISS could pin their hopes on. They had obliterated Jacksonville in such convincing fashion that two years of futility seemed to vanish instantly. The question of whether they were any good, or the same old lousy KISS, had been answered. They felt like they had the makings of a champion.

On the team’s first day back to work, everyone’s confidence was infectious. Joe Windham, the team’s president and CEO, paced the front of the room, practically giddy with excitement. He clutched his smartphone at a distance so he could read the good news without needing reading glasses. The team had barely settled in when he began speaking with the energy of an infomercial pitchman.

“Season tickets, bought and upgrades. Lotta buzz; Facebook, 900% increase in posts! 10 minutes of talk on sports radio!”

He looked up after each bullet point, wanting their importance to sink in. Joe wrapped up his speech by saying that Gene and Paul were very pleased.

To learn that the rock star owners were proud made the men swell with pride. They looked at each other in amazement, impressed by those simple words more than any social media metric or sales figure.

Coach O then took the floor to address his team. He congratulated them on the win, but cautioned that it wasn’t perfect. The pass rush needed to be better, he said. As good as they had played, a lot of lucky breaks went our way. Without Jacksonville’s three missed extra points, two fumbles and one kickoff that clanged off the uprights back to the KISS, they were talking about a whole different game. Their next opponent, he warned, would not be as forgiving.

The Arizona Rattlers were a perennially successful team that, in the ever-changing landscape of the AFL, somehow maintained great talent year after year. They had won three championships in a row, from 2012 to 2014, and narrowly missed out on a fourth, due to a controversial fumble in the end zone that gave San Jose a 70-67 win in 2015. Omarr Smith had been San Jose’s assistant head coach that year, and a lot of the guys in this room had been there with him. They knew the Rattlers all too well. The very mention of their name darkened the room and struck fear, jealousy and hatred into even the most grizzled of L.A. veterans. It was widely believed throughout the entire KISS organization that Arizona paid their players under the table. Of course, that could have been just a bitter way to explain why the KISS had never beaten the Rattlers before. (Months after I left the team, I asked Arizona’s head coach/GM, Kevin Guy about this. He said, “Teams that make these accusations are usually teams that don’t put the work in, and they build in these excuses on why they’re getting their a---- beat.”)

The entire room watched the tape of Arizona’s 80-28 destruction of the Portland Steel as if it were news footage of a natural disaster. Everything Arizona did looked devastatingly easy. Of course, playing Portland helped. That entire team was a disaster.

Arizona waltzed seemingly nonstop into Portland’s end zone, where the old red and black PDX Thunder could still be seen underneath the new blue and silver logo of the Portland Steel, which didn’t cover enough of the carpet to erase the old name. The AFL, which had repossessed the franchise a few months before when a contract dispute went awry, was making the barest of investment on this team and it showed. Rather than let them fold, they were now run by the league so there’d be enough teams to play the season, and seemingly to give teams like Arizona someone to beat up.

“At a certain point, it’s gonna be us and them to get to the Arena Bowl,” Coach O said matter-of-factly. “In my opinion, it’s us and them, and then Philly, as the best teams in this league.”

He switched gears and reluctantly brought up another matter.

“Food vouchers,” he said. “You’ll get four. If you need more, I can get four more. So, pretty much, you’ll get eight. After that it’s five bucks a ticket.”

“We win a game and we gotta buy our food?” BC asked in disbelief.

“Last week, there were a lot of unused tickets,” Coach O said. “Like 50, 60 tickets. They pay for that and they get pissed.”

It was cheap and indefensible. Everyone knew it. Even Omarr, who looked embarrassed to bring it up.

As we sat down in our position meeting, the mood was still positive. I noticed a new man in our group. Dan Buckner, or Buck, had just been cut by Arizona and brought in on a two-day waiver. He was a big-bodied receiver who’d spent a lot of time with the Cardinals in the NFL. He watched us without a word as we took our seats.

We were reviewing the tape from the Jacksonville game. Midway through, we saw Nate Stanley put a touch pass into the hands of Brandon Collins.

“I don’t think that’s a very good play,” said BC, suddenly.

“We went two for two on that play,” said Nate, shocked.

“S---, didn’t you catch it?” asked Coach O, turning to BC.

BC paused a moment, then a grin grew in the corner of his mouth

Laughter rippled across the room.

Another highlight showed Amarri Jackson take a vicious shot to the hip. He crumpled to the turf and was slow to get up.

“That’s them thin a-- fragile legs,” said D-Mo.

“I’m hurting now,” said Amarri.

We all turned toward Amarri and nodded, concurring like doctors.

“Nah,” he said, rubbing his wounded hip, “for real.”

Then he smiled, giving the appearance that he was having the time of his life despite the pain. The room burst into a second eruption of laughter.

Buck’s eyes darted around the room. At certain times he focused on the plays, but other times he seemed to catalogue everything: friends and foes, strengths and weaknesses. He was always alert. He would laugh when the others laughed, but just a beat later, as if he were learning our jokes along with our plays.

After the highlights were done, Coach O turned to Buck and asked him point blank, “What we can expect to see from Arizona?”

Buck laid out what he thought Arizona would run, how they would react to certain plays, how they would try to cover the KISS. Everyone listened with rapt attention.

After Coach O released us, and after the players left the room, I asked the obvious question: “Did you bring Buck in here just because he was in Arizona?”

O shook his head.

“No, I know they’re system better than he would. Remember I coached there.”

That didn’t make sense, I thought to myself, why ask him about Arizona then?

“One last thing,” I said, switching gears, “when am I going to suit up?”

He thought for a second.

“Tomorrow,” he said.

I swelled with fear and pride. This was it. Finally, I’d taste the field. Eager to get more reps in before the big day, I quickly got taped up in the trainer’s room and wandered out early to the field. The JUGS machine was already firing bullets to a queue of receivers. I slotted myself in behind Buck and introduced myself.

“I’m the writer,” I said.

“Everybody told me you was the all-star,” Buck said, coldly.

So that’s how it’s gonna go, I thought. I was not his friend that day, I was someone whose spot he had to take. I was both confused and delighted that no one ever believed me at first. Secretly, I hoped it was because I actually looked like a football player.

As the team whipped through its day, I kept an eye on Buck. Plugged in at both receiver and Jack linebacker, he was a dynamic two-way player who could take a hit just as easily as he could dish one out; his versatility was his value. He was what the team was missing while Terrance Smith remained sidelined by injury. He was tall and powerful, with good hands and a bit of a mean streak. He looked like could play at any level.

The team’s trainer, Jesse Geffon, was nearby, watching receiver Mike Willie rehab an injury. Before this job with the KISS, Jesse had spent time as a trainer with Cirque du Soleil—a perfect primer for the circus of the AFL.

“Is this league a catch-all,” I asked, “like a bin for unused talent?”

He nodded, amused by my obvious question. It was as if I’d asked him if the grass was really green.

“The skill players in this league could all play at the next level, but there’re only so many spots. It’s the O line and the D line where you see a major difference in talent. Look at sixty-three,” Jesse said, pointing to a new two-day waiver man who was trying to break in on the defensive line. “Perfect example. He’s going to have to really impress. There’s only four down linemen, so he’ll have to replace one of the starters.”

He was pointing at Manny Wright, a college national champion at USC, a Super Bowl winner with the Giants, and now here on a waiver, hoping to take someone’s job. I watched Manny for a beat. He breathed hard between plays. His bright yellow Batman cleats gleamed in the So Cal sun and sweat streamed down his forehead. He took in water and held his hands on his hips before crouching back down for the next play. He looked exhausted.

“Are guys always on a tryout here?” I asked.

“Every day, it’s that kind of league,” Jesse said.

After practice, the team went to the weight room. On my way to join them, I ran into Manny. I was intrigued by his story, but one question fascinated me: What was a Super Bowl winner doing here? I introduced myself again, but he remembered me from our open tryout in February. Behind us, hip-hop and clanging iron poured from the open door of the gym as the KISS grinded through a workout.

“So, why the KISS” I asked.

He shook his head, still sweating from practice.

“I just want my son to see me play,” he said. “Because it’s local. When I played in the Super Bowl, he was 1, so he didn’t get to see me play. But he’s seen me run, and he’s like, ‘Damn dad, you’re fast, but you’re fat. You’re skinny-fat.’ So I just want him to see me play. And maybe bring something back to L.A.”

The simple nobility of his answer surprised me. I thought of his son listening to his dad tell him stories that must have sounded impossible.

“How much longer will you give the game?” I asked.

“Maybe just two or three more years.”

“Do you want to go back to the NFL?” I asked.

“Nah. I’ve played at every level, so…”

He shrugged. What else did he have to prove?

Manny and I made our way inside. Coach Donnelly barked at the men as they went through their routines. I tried to lift with everyone. I did well, but met my limits on the dead lift, where I maxed out at 320 pounds. Watching me struggle through my fourth rep, Donnelly stopped me.

“That’s it, Neal. You’ll hurt yourself.”

Funny, that had never stopped me before.

* * *

April 6, 2016

Almost no one gets up in the morning wanting to be hit or looking to hit someone else. Some 10,000 years of civilization have protected us from that dog-eat-dog brutality. Our laws favor the cleverest among us, not the strongest. But that’s not true for our modern-day gladiators. Violent collisions are an everyday part of a football player’s job. (Except, of course, for kickers and quarterbacks.)

I woke up with the realization that I was going to be on the receiving end of these encounters. I was oddly excited by the idea. Finally, I thought, a chance to mix it up. I wondered what it would be like. A car accident? Would I stumble around, dazed, trying to piece my world back together? Would I pop up immediately, trash-talk the man who’d leveled me and say in a thin-Eastwoodese, “Is that all you got?” Or would it be like a fight? I’d only been in three of those—they were all in high school against boys my own age, but much shorter. I couldn’t really count those hormonal haymakers as fights though. Still, I consoled myself with the thought that I was 2-0-1, my only tie coming when my dad wandered into the pre-fight mob pretending to be a concerned stranger.

“Hey, Neal, isn’t that your old man?” a kid asked me.

“No, my dad’s a Navy SEAL. I’ve never seen that guy before.”

Truth was, I had no idea what to expect. This was going to be something totally different. As I sat down in the morning meeting, the team was excited too. Not about hitting me (although that’s a possibility), but still high off their big win over Jacksonville. They chattered brightly and ate bacon and hash browns off paper plates, convinced they were destined to be champions. The room grew quiet when Coach O walked in.

“Practice hasn’t been very good,” he said. “We’re not gonna win on Saturday, considering who’s coming to town. You don’t come and compete, you don’t win championships … We’re talking about a whole different ballgame. You got a bully coming to town, you can’t be no punk.”

Again, Coach O took the air out of the room. The players’ smiles faded away, leaving just a grim determination to prove themselves on the field.

Can’t be no punk. I rolled the thought around in my mind. They seemed like words to live by.

As the rest of the team dressed for the day’s work, I asked Jay, the equipment manager, for pads, a helmet and a jersey.

“I don’t know if we have anything that small,” he said.

“That’s clever,” I replied, with a tight smile.

With a smirk, Jay handed me a used black helmet, shoulder pads and an extra large jersey, number 80, which I had no hope of filling out. He buckled the pads onto my shoulders, and with a series of strap pulls and snaps, I was locked in. I slipped my jersey over my pads, and what had been too big before now fit snugly around my shoulders. I grabbed the helmet by the ear holes, pulled it open and fixed it onto my head. I looked down the hallway through my new tunnel vision and felt what George Plimpton spoke of, “Like a gunner, safely in his turret.”

“How’s that feel?” Jay asked.

He slapped me on the back of my helmet. I could barely hear, let alone feel, the slap. It was muffled and distant, not a part of me somehow.

“Good,” I said.

My cleats made me taller; my shoulder pads made me wider; my helmet gave me the illusion of invincibility. I felt like a giant. Confidently, I made my way to the field where my moment was waiting.

“Oh, damn!” said Clevan Thomas, as we walked toward the field. “Neal! Neal the thrill!”

Other players looked shocked to see me in pads. They had warned me about how much getting hit would hurt. I was also warned that there would be a learning curve to catching the ball with a helmet on, but it wasn’t difficult at all. In fact, the safety of the helmet put me at ease. The usual tension I carried of trying to not to look like an idiot was gone. The helmet was my refuge from the world.

As practice got rolling during special teams, my number was finally called. Coach O looked over from his play sheet and caught my eye.

“You’re up,” he said, giving me a nod.

I was confused instantly.

Up?

Up where?

I saw nose tackle Gustave Benthin, the baby-faced dad from Oregon, trotting toward me. My mind was reeling. I’m taking his place? But he’s 300 pounds!

Upon entering the huddle, I was met with wide stares and silence.

“Who do I block for?” I asked grandly, trying to convince them I knew what I was doing.

More silence.

“Uh, no one,” said one of the stunned players, “we’re kicking off.”

I looked at him blankly.

“We’re on defense,” he continued.

I turned a helpless eye toward Coach O. As if sensing my confusion, he was already looking right at me.

“Just get your assignment from Coach Davis,” he called.

Coach Wendell Davis came over and kindly showed me a diagram of the play. I was told to line up in the middle of the field. My assignment was to curl around toward the sideline on my right and run at the ball carrier, in the shape of a J. At the far end of the field, DJ Stephens scraped his cleats in the grass, like a bull poised to charge.

I had this.

Andre Heidari, the new kicker, looked left and right, his right arm raised in the air as we got set. With a nod, he ran toward the ball and booted it high toward DJ. I took off and sprinted down the field, untouched by anyone. I was so focused on getting to the end zone, on executing my ‘J’, that I barely noticed DJ slicing through the middle of the field to my left, the football tucked snuggly in his arms.

Oh, right … the whole point is to get after the ball carrier!

I trotted back after the play was whistled dead, feeling like a moron but even more determined. On the next play my assignment was to run straight down the middle in the shape of an ‘I’. Across the way, directly in my path, all 265 pounds of Derrick Summers stared silently back at me.

Damn.

Andre kicked off again and I hurtled myself toward the far end of the field. I ran right at Derrick like a howling Highlander from Braveheart. He grabbed me effortlessly and pinned me by the shoulders. I writhed violently and tried to free myself, but nothing I did had any effect.

Beneath his helmet, Derrick smiled sweetly at me.

“It’s alright, I got you,” he said, gently.

I trotted back to the line again, having learned a valuable lesson. Fight harder, can’t be no punk!

I had the same assignment on the next play. Andre kicked and I was off like a missile. In my path this time was not only Derrick, but another linebacker as well. They wedged me. Any hope I had of breaking free was futile, but I refused to give in and fought this double-team with everything I had. My arms swung wildly, and my body thrashed against their vice.

“Damn, he tryin’ to kill me,” the other linebacker said.

Derrick looked at me again, amused.

“You good,” he said from beneath his mask, perhaps trying to put me at ease.

Football is a tough game, but it’s even tougher for those trying to break in and earn their reps. In my brief time with the LA KISS, I had seen many two-day-waivers be given their shot at special teams first, which is ostensibly a human demolition derby. If they were willing to sacrifice their bodies, they were given a second look. Obviously, there was nothing special about me on special teams.

I asked D-Mo how tough it would be for a two-day man to make the team.

He laughed.

“You gotta beat out all these other veterans,” he said. “Come in against first team and light they a-- on fire.”

I had my chance a few minutes later. Coach O subbed me in on the second-team offense and I joined the huddle. A cheer rose from the defense; their Rudy had just been subbed in. I waved to them like a daredevil climbing into a rocket. Pete Thomas, the backup quarterback, barked out a play; the rest of the players nodded silently and clapped their hands to break the huddle. My instructions were explicit: just run a simple hitch and I’d have my first pro catch, easy as pie.

I took my spot at flanker on the far side of the field. Across the way at cornerback, Fred Obi flashed a wolfish grin and lined up as close to me as he could get. I shivered with nerves. My eyes bugged out of my helmet and my body felt like it would start levitating at any moment. I had lost the ability to perform even the most basic of physical tasks and I doubted if I’d be able to run and catch. I wasn’t scared; I was electrified.

“GO,” Pete growled.

I jumped, confusing the motion man’s start signal for the hike. I planted back down, mortified.

“Hike,” yelled Pete.

I ran right at Obi, planted and tried to spring back, but the ball sailed wide to my right. It could have been underthrown, but I was so juiced that it hardly mattered. I had run well past my five yards.

“You can’t move until the ball is snapped,” Coach O said, calmly.

“Oh, uh, yeah, I know,” I said.

Back in the huddle, Pete called the play again and the players broke. Then he turned to me.

“All you have to do is just block Obi on this one,” he said.

I nodded.

My mind was still on the last play, and I jumped again when I heard Pete yell, “Go!” Obi sniffed out the play immediately and stepped into backfield as if I had invited him over for dinner. Luckily one of the tackles burst in before him and made the play. On the film, it wouldn’t be my fault.

“Let’s get it right!” yelled Coach Hous. “You only been out here three f------ weeks!”

Pete took me aside in the next huddle and calmed me down.

“You can’t move until I hike the ball,” he said.

“Oh, uh, yeah,” I stammered. “It’s just, I keep thinking go is hike.”

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “Next one’s a screen, and I’m coming right to you. You don’t even have to move.”

I trotted back out. Obi gave me a smidge more respect and walked back five yards. He was expecting a track meet. I smiled. For the first time, this little piggy knew something the big bad wolf didn’t.

“Go,” said Pete.

The motion man took off, but my feet stayed rooted to the ground. Obi adjusted, taking two steps in my direction as Pete hiked the ball. I turned in place. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Obi sprint toward me as I waited for the ball. Three steps into his drop-back, Pete turned and fired. This would be it. My hands spread instinctively into a diamond. At the same time, a defensive end got the angle on the guard and reached for the passing ball. It caromed off his paw and fell lamely to the ground. The play was whistled dead. That was it. A new group subbed in.

I saw Joe Windham stalking the sidelines. He looked at me curiously and suddenly Coach O was all business again. My look was done for the day. I hadn’t lit anyone’s a-- on fire, except maybe my own. I hadn’t even gotten hit yet.

* * *

Clevan Thomas is a deeply religious man. He constantly studied the bible and wore his beliefs openly. He would drop bombs of faith like people drop names at Hollywood parties. In our very first conversation, he told me he didn’t believe in the Big Bang because “the Big Bang didn’t mention blood.” While I disagreed with his facts, I couldn’t argue the strength of his beliefs. His come-to-Jesus moment had been a true near-death experience.

During a team huddle before practice one day, as the cuts loomed overhead, he tried to fire up the team. “I had a dream last night, about a girl’s basketball team,” he told us. “Some would make it, some would not. I asked God for guidance. I would have been a second-round draft pick [in the NFL], but I failed a marijuana test right before the combine. I tried to commit suicide by taking one ecstasy pill every hour, then I found God. You have to humble yourself to him … Run after God, keep your focus on him and he will provide for you.”

Given his stature as one of the best players to ever play at this level, Clevan’s voice was always heard during every huddle—and he always peppered his speech with a reverence for his savior. He was, in many ways, the team’s chaplain. After every practice he led a prayer circle.

I asked him if I could join.

“This is God’s circle,” he told me, offering an invitation and a warning.

Once inside we joined hands and reflected, one by one, on what we were grateful for. Each man was given space to be vulnerable, something that was very much at odds with the violence of his profession. It was here that I gained a better sense of who they were. Their physical acts were admirable, but it was their struggles with family and life that made them genuine.

Soon it was my turn. I thanked them for all these firsts. I thanked them for letting me into their lives. I had never played football before, and I wanted them to know how honored I was to briefly share their field and their journey.

When it was D-Mo’s turn, he thanked Rogaine for Rodney Fritz’s balding scalp, which sent everyone into fits of laughter. Then it was BC’s turn. He thanked the lord for getting him out of legal trouble. A pending suit back in Texas had been dismissed.

“I was in a place I shouldn’t have been in,” he said.

“It was dismissed,” said Clevan, as he clutched his hand next to him and leaned in to face him.

BC fell silent.

“It was what?” Cleve kept repeating.

“Dismissed, dismissed, dismissed,” BC said, letting it all go.

BC centered himself, the wave of relief having passed, and his eyes shot up to the rookies.

“Also,” he continued, “I’ve been where you are, I watched from the bench all last year, waiting for my chance. So I know what that grind is too.”

We held one another’s hands, stared into the earth, and recited the Lord’s Prayer. “Our Father, Who Art in Heaven…”

Afterwards, the men’s hands fell onto one another’s shoulders. I felt a heavy slap on my shoulders too. This time it didn’t feel distant, like Jay’s slap on my helmet, but close, an appreciation that every day we were a little more like brothers.

* * *

April 8, 2016

It was a gloomy and miserable Friday. A thick blanket of gray clouds hung low above Santa Ana, while a layer of heat and humidity slowly cooked everything beneath it. Despite the gloom, there was a festive atmosphere at practice. Many of the players had strange hats on. Kody Afusia wore a crown. BC wore a woman’s gardening hat. Mike Willie, a black Abraham Lincoln stovepipe. Others, who refused to play dress up, just wore their baseball caps backwards.

I asked Mike Willie what the hats were all about.

“Just on Fridays we wear funny hats, is all,” he said, as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

That was also the morning when I started to get the feeling I wasn’t welcome anymore.

Just after the team meeting, Coach Hous brushed past me, smile f------ me as he said, “Hey, Neal, how’s things?” He’d always been distrustful of me, but now I felt his menace unleashed. But mainly I felt unwelcome because of what happened afterward, at the position meeting.

There was a definite chill to the room. I chalked it up to the fear of Arizona. Coach O barely looked at anyone. He mentioned that he had watched tape from the night before and didn’t like something he saw. He wanted to install a whole new offense. The game was just a bit more than 24 hours away. How the hell was he going to do that, I wondered?

Just then, Dan Frazer, the director of player personnel, popped his head into the room to grab Buck. There was something wrong with his contract. Buck followed him out into the courtyard. Coach O stopped and looked at me square in the eyes.

“Neal, could you give us a few minutes?”

Definitely overstayed my welcome, I thought.

Outside Dan went through the finer points of Buck’s contract like a used-car salesman. I stood there, feeling useless.

Everyone eventually came out and streamed toward the gym, where we would practice because of the rain. Inside, the lights were off. A group of big Polynesian linemen started to fling around a rugby ball, while the rest of the team, white and black, tried to convince one another how good they were at basketball. Someone put on some music, soft rainy day jams, which kept the mood mellow and easy. Mariah Carey then Michael Jackson. When Warren G and Nate Dogg slipped into “Regulate”, several players started to quietly bob along to the music. It was just a big indoor recess.

Coach O called the practice to order and the first team walked briskly through the game plan. One play and then the next; the outdoor game compressed further still on the basketball court. Then Coach O announced we’d play another game—a basketball shootout comprised of a 3-pointer, free throw and layup. Whoever got all three first won the round. The team was split into two groups and players went head-to-head, two at a time. The “bigs” went first and it was knotted at 4-4 when they were done. The “skills,” men who considered themselves two-sport athletes, went next.

I stood on the outside watching. Coach O’s dismissal from the meeting room made me feel unwelcome and I awkwardly paced the sidelines. Amarri Jackson sensed this. He came over to me, took my arm and spoke in a hush.

“Between you and I,” he said, “the reason we had to kick you out was that someone was talking to Arizona. We know it’s not you, but we had to make it look like all people who aren’t under contract had to leave.”

I was stunned.

“Buck?” I asked.

He nodded.

Could that possibly be true? If they felt they had a leak, it would make sense—the coldness to the room; the panic about Arizona; Coach O announcing he would install a new offense at the last moment. Maybe this league was more cutthroat than I knew. Or maybe it was all a bunch of paranoia.

It seemed unlikely, but I had to ask Buck if he leaked any plays to his former team.

“No,” he said, “of course not.”

I asked him why he thought the KISS would believe that.

“He wanted to beat Arizona, working hard, not getting a lot of sleep, just paranoid,” he said of Coach O.

BC, who was Buck’s friend and college teammate in Texas, sprang to his defense.

“None of that s--- was true,” BC said.

So it was just paranoia?

“I think so, because I know Dan,” BC said. “Dan has a daughter, right? So if you have a daughter and Arizona fires you, that takes food out your daughter’s mouth. Omarr brings you in, gives you a job, he’s putting food in your daughter’s mouth. Why would you then go back and give them those plays? That doesn’t make sense.”

I had to agree. Buck seemed like he was just trying to break in with a new team. I couldn’t fathom him being a secret mole, sent by the Rattlers to infiltrate the KISS. I asked Coach O about it later, if he thought Buckner was giving plays away, and he immediately denied it.

“No, I didn’t think he was giving plays away, so whoever told you that was incorrect,” said Omarr. “Dan Buckner had just come from Arizona, and the fact that he wasn’t on our roster put me in a position where I could possibly be compromising our team.”

I asked if that was the reason he wanted to install a new offense the day before the game. “No. That had nothing to do with it,” he said. “You see things in practice that you don’t like, that you might want to tweak, that you might want to try. Sometimes that happens early in the week, sometimes that happens later in the week.

“Every game has pressure. Regardless of who you’re playing. There wasn’t more pressure that game … going into that game, I was just concerned about our team having too much confidence.”

To hear Coach O tell it, everything had a simple answer. But then why ask me to leave the room? Why not be straightforward with Buck? Omarr certainly wasn’t this cagey with other players. Why feint that he didn’t like the offense, only to walk-thru that very offense minutes later? It was all very strange.

D-Mo offered his view.

“It came back to us that it’s a possibility that he might be telling them what we’re doing,” he said. “Buckner wasn’t on contract at the time, and he wanted to play so bad, we thought he might sabotage the game.”

In other words, they feared Buckner’s desire to play anywhere was so great that he’d do whatever it took to secure his spot. The thinking went that if the KISS tanked, then there would be an opening for a waiver man.

“We wanted to see if it was true,” D-Mo said, “we wanted to see if he was spilling the beans or not. We didn’t have any hard evidence, it was pretty much speculation.”

Should they have been so paranoid? More on the Arizona game in a bit…

Back in the gym, there was tension and doubt beneath the recess ease. I watched as Amarri lined up in the basketball game against Buck. Buck was a great sharpshooter and won easily. Afterward, he smiled and joked with the KISS. If he really was a mole for Arizona, maybe he was trying to play both sides. Or maybe, more likely, BC was right, and Buck was just looking to fit in with his new team.

The shootout was tied at the end and it came to down to two out-of-shape coaches, Coach Shaw and Coach Wat, to break the deadlock. Shaw bricked three after three while Wat air-balled everything as if he’d never played before. Even though Shaw was better, Wat got on a lucky streak, hitting a three, a free throw and a layup to win it. Everyone went wild.

Coach O then stepped in and focused on the real game still to come. He was fired up for Arizona. His voice roared and he used all the energy of his small frame to conjure up his passion and hatred for the Rattlers. He wanted to win badly.

“Tomorrow is our time to show the league we’re the best team in this motherf-----. F--- them,” he yelled.

There was a chorus of agreement echoing his damning curse.

“Motherf--- them,” added a rabid Coach Hous, before putting a final point on it. “Put that in Sports Illustrated.”

“We gotta whip they a--!” implored D-Mo, leaping to his feet and looking around. “They already talkin’ s---. Sayin’ they can go out the night before the game. Sayin’ they don’t have to prepare for us. They don’t respect us! No dappin’, no shakin’ hands. We gotta go out and stomp they a--. This is real s---, ya heard me?”

“Enough said,” finished Omarr.

* * *

After practice I drove back to L.A., but the gloomy weather slowed the commute to a crawl. I was demoralized and famished; by the drive, yes, but also by the way things had ended—me on the outside looking in. I didn’t know what to do with myself for the rest of the day. I was so used to being on the conveyor belt of a schedule that I was paralyzed by this free afternoon. I decided lunch could take care of my hunger, if not my ennui.

There’s a hip little sushi counter attached to my parking garage. (I’d mention it by name, but the lines are already long enough.) Miraculously I was able to get a spot at the bar without a wait. I crammed myself in to eat and looked at my notes. The usual crowd was there, a mix of men trying to impress dates with haute cuisine near Skid Row, and the local creative class who needed fuel to dream up their next app, sneaker, or track on SoundCloud.

A hog-bellied hipster stood a few feet away from me as I ate, loudly negotiating over the phone. I turned to face him. He was dressed like a second-rate Coachella DJ, and he had a thin strap of a beard giving his fat neck a whisper of a chin. His talk sounded superficial and cheap. He jabbered on for five minutes without regard for anyone else’s peace, but more likely to enforce the illusion of his preeminence. I fantasized about tackling him. But the better angel of my nature won out and I decided he wasn’t worth prison. Instead, I just stared at him until he became uncomfortable and stepped outside.

He represented the L.A. I had grown to despise. The superficial Candy Land where everyone was a self-proclaimed king. Here was a counterfeit watch of a man peddling himself as the real thing. I had just come from a land of counterfeit objects peddling themselves as real things, but football at least tests you and forces action. You had to back up your talk. Either your watch worked or you got your clock cleaned. It ruthlessly exposed charlatans. Back in this L.A., it was all just bloated talk, Instagram likes and leased luxury cars.

Back home, I put my cleats back in their box and sat on my bed. As I stared into the gray outside the window, I felt odd: I had nowhere to be. For the last six months, every meal, every minute, every day had been given to football, and now the game was gone. For the briefest of moments I sensed an absolute paralysis and was gripped by indecision. I could go to the gym, I thought, but then, what’s the point now?

I thought about getting really drunk.

* * *

April 9, 2016

It was game day and Arizona had come to town. The crowd at the Honda Center was noticeably smaller this time, filling only a third of the arena’s capacity. Despite the size of the crowd, the building felt ready to explode. Gene was there, but Paul was at home, recovering from shoulder surgery. Even still, the team seemed fired up. There was a sharpness to their preparation. The importance of this had been drilled into them. They knew the stakes: win at all costs.

Joe Windham, the CEO, seemed especially anxious as he paced the media pit behind one of the end zones. He pointed to an empty group of tables at the far end and told me he’d set it up as a celebrity section.

“Mel-B from the Spice Girls, she’s here, and you know Dog the Bounty Hunter?” Joe asked.

I nodded.

“His wife!”

Former Dodger Todd Zeile was here too, to flip the coin before kickoff. It wasn’t much, but it was a start.

“Have you seen a spike in ticket sales?” I asked him.

“It’ll take a while,” he said. “It’s L.A. We have to keep winning. But if we beat Arizona tonight, especially if we beat them the way we beat Jacksonville last week, then it’ll send a message.”

Sadly, Arizona sent the message, loud and early. They were up 14-0 before most people could dip their first nacho. They jumped plays and scored with ease. As the KISS grew frustrated, their execution became sloppy.

Soon, the lead became insurmountable and the announcer implored fans to get inside the helmets of Rattler players. But the crowd was too small, too bored and had no winning tradition to fall back on. They knew only the monotony of dull defeats and the building remained silent.

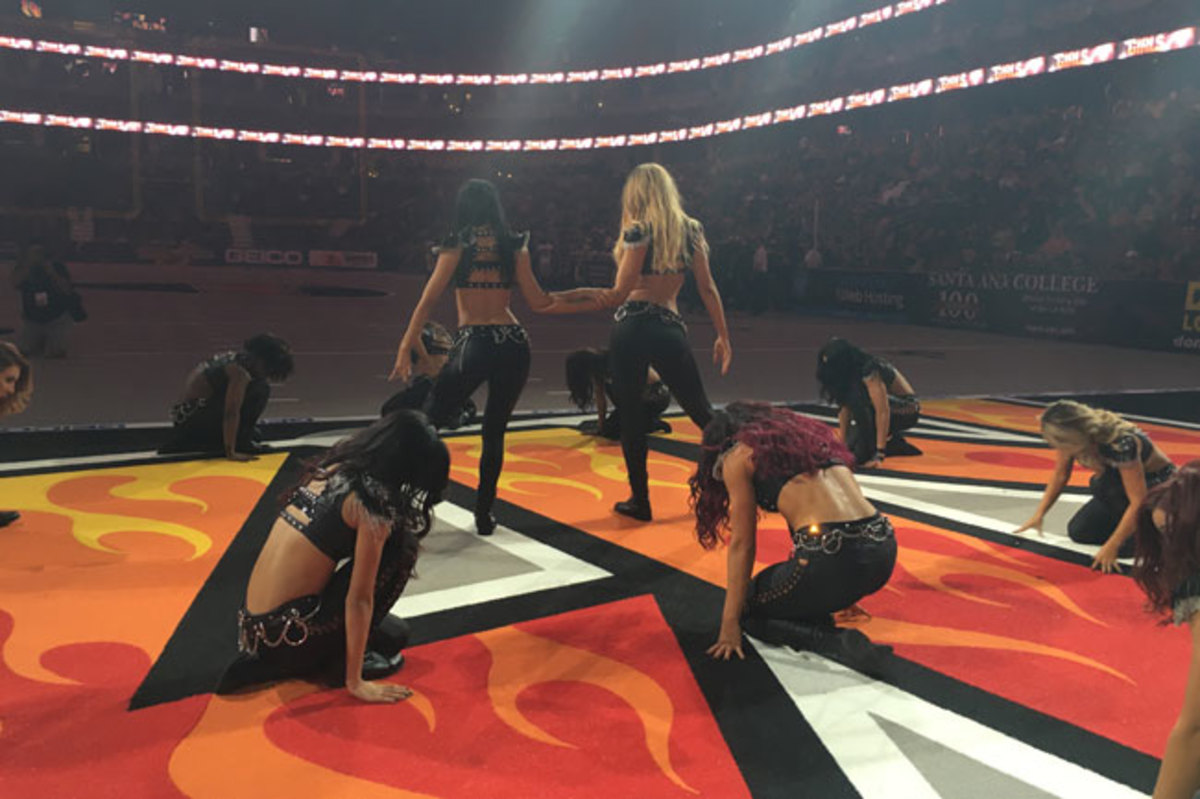

The KISS Girls, dressed in spandex, leather and chains, tried to rally the crowd. They gyrated around the stage, while leering photographers in the pit below turned around and switched lenses to capture their moves. Several of the photographers seemed to take more interest in the dancers than the game itself. The KISS Girls frolicked provocatively around the House Band, as if songs that were popular before they were even born held the power to transform them into vixens. The music seemed to get louder while the PA announcer strained his voice. If you ignored the scoreboard, you almost believed it was a party. The more out of reach the game became, the more the entertainment seemed out of place. It was like feasting on a lavish buffet at the campaign headquarters of a losing candidate—the trimmings of celebration amidst the hollowness of defeat.

Omarr desperately tried to keep his men focused, but everything fell to the raging Arizona machine. D-Mo seemed to take it the hardest. He left the field after another three-and-out with a loud, “S---!” I looked up and caught his eyes. He immediately cocked a grin, as if assuring me that everything was all in hand, and his bulletproof armor sprang back up. Through the rails, I caught sight of Rodney Fritz and Clevan Thomas’s despondent faces.

The final score, 69-28, said it all: any chance the KISS had to make L.A. sit up and take notice had been kissed goodbye.

I asked D-Mo if he saw any evidence that Buck, who bought his own ticket and sat in street clothes behind L.A.’s bench, had been a mole for Arizona?

“Uh, I don’t know, they was calling out some of our plays,” he said, “but that could be because they’re so used to Omarr [he was the defensive coordinator there from 2011 to ’13].”

Of course, when I spoke to Arizona’s head coach, he was much more blunt.

“We would never need Dan to tell us anything!” Kevin Guy said. “They were the most predictable team in the league. Dan Buckner would never do anything like that because he has too high of a character—and, oh by the way, it’s not a rivalry until the other team beats you! It might’ve been a rivalry for them but we never looked at them that way.”

After the loss, the Arena’s buzz evaporated into thin air. All that remained was a reflective quiet, like the muzzle that chases an audience out of a depressing film.

“How we doing KISS fans?” the House Band asked, as most of the fans streamed for the exits. There was no response, just a steady exodus. Very few fans remained in the building, but the House Band wasn’t deterred. “We know the party’s just getting started!”

But it was a lie. The house lights were on and the party was over. The band dutifully played us out, and the dull shuffle of our feet was soon drowned with KISS anthems, exit music ushering us into the night.

* * *

To their immense credit, the KISS players met a few hundred fans on the field that night and signed autographs after the blowout loss. As always, D-Mo’s line was the longest. Afterwards, they went to the Tilted Kilt, just like they always did, and the players, coaches, KISS girls and fans, raised a glass to a better tomorrow.

My time was done and I skipped the bar that night. I left Anaheim behind and drove to a late-night spot in Brentwood to meet a friend. As I turned off the 405, I was reminded of O.J. Simpson and the inextricable link between celebrity and football in Hollywood. I may have been driving through that neighborhood, but I was nowhere close to either end of that spectrum. I was heading back to obscurity amongst the opulence. I parked outside the bar, lucky to find a spot by the door. I tossed my ball cap into the backseat and put on a fedora, literally changing costumes. I paused briefly to breathe in the night, dreading going back to it all.

A slick-looking bouncer with a proud belly, coiffed hair and thick black glasses flung the door open and strutted out. He threw a piece of garbage into the trash, wiped his hands and chomped on a toothpick. I must have startled him, but he was the type who didn’t appear to be startled by anything. He was a veteran of a different kind. Not football, but the great status chase. He eyeballed me, calculating my worth.

“You coming in?” he asked, rolling his toothpick from one side of his mouth to the other.

Behind him, the promise of sex, music and Hollywood spilled out onto the street. I heard the sound of clanking glassware, the laughter of women and the boasts of men.

I looked at my feet and softly sighed. Yeah, I nodded. He let me open my own door, and I was back in. The first person I saw at the bar was Cuba Gooding Jr. Another actor, famous for playing football players, who, having been shown the money, was having the time of his life, welcoming me back to L.A.

Part 1: A Man, the Arena, and His First KISS of Fate

Part 2:A Quixotic Bit of Foolery

Part 3:Judgment Play

Part 4: ‘A Very Attractive Man of Great Sexual Power’

Part 5:Arena Dreams: In Search of 26 Riders

Part 6:As a Realist, You Should Know Anything Can Happen

Part 7:A Bully Comes to Town

Next Friday, in the conclusion of the Delicate Moron, Neal hits the road for the LA KISS’s first “home” playoff game and finds tragic comedy at every turn. All that and more in Part 8.

Question? Comment? Story idea? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com