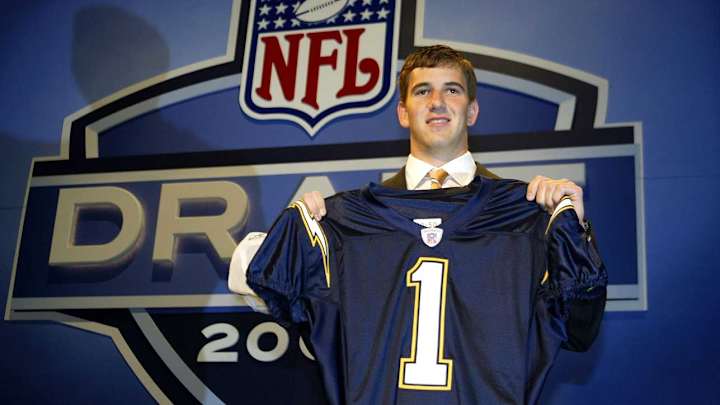

Eli Manning Shouldn't Get a Pass For Ducking the Chargers in the 2004 Draft

Welcome to Bad Takes Week, where MMQB staffers have been asked to expand upon some of their worst football takes. These are columns on the ideas they believe in strongly, even if it makes the rest of the room groan during our pitch meetings. Keep an eye out for more of these throughout the week.

On Friday, April 23, 2004, there was a headline in the Sheboygan (Wisconsin) Press that read: MANNING’S ‘REQUEST’ ANNOYING.

The 219-word hot take, which landed on page 1B of the sports section, summed up in all practicality the criticism Eli Manning faced for his decision to basically subvert the NFL draft process with the help of his family and agent, play for the team of his choosing and sink the reputation of the Chargers and their new general manager in the process. Annoying, indeed!

“It's normal for kids to have preferences,” the editorial read. “But to try and force a team's hand and hijack the draft process? That's way out of line and it stinks.”

This particular passage—to me—is just so perfect. This was sports discourse from another time; like watching politicians debate pre-2016 and hearing things like, “I respectfully disagree, sir, and will flesh out those thoughts in a strongly-worded opinion column in the New Republic!”

Outside of a few outliers (one columnist called Eli ‘jughead,’ one called him a ‘brat’ and one extremely bad column in the Seattle Times chided Manning for not being more like Pat Tillman(?), it seemed like there was a camp of old-time hot-takers whipping up the helicopter parent trope (the precursor to the coddled millennial stance), but then a small army of Manning-sympathetic columnists coming to the family’s defense. Their argument? Archie 3D chessmastering the draft was the kind of thing any concerned father might do.

That’s it. No anonymous scout clubbing Manning at the knees for the same exact kind of emotional distance they’ve used to fuel a blowtorch for other prospects. No “AFC executive” saying that Manning’s willingness to take a year off to attend law school signals that Manning may love justice more than football, aka, a major red flag.

At the risk of sounding whiny, I guess my bad take is: Why didn’t Eli get more s--- for what he pulled in 2004? I know it’s not perfect, and maybe Eli represents some underlying psychological tipping point from my past, but I have ruined several nice get togethers among friends in New Jersey by bringing this very bad take up.

I sometimes imagine Eli sitting at a bar, drinking with some of the other first-round quarterbacks who have been drafted more recently. After several High Lifes, the conversation turns to the media steeplechase everyone had to go through prior to the draft.

Lamar Jackson: I remember when my mom wanted the best for me and opted to manage my career, which snowballed into a hell storm of coded attacks and, eventually, the thought that I should probably play receiver instead of quarterback. I ended up nearly tumbling out of the first round.

Josh Rosen: I remember that time my naturally inquisitive disposition and love of the environment was turned into a harbinger for the end of football’s military industrial complex. I slipped outside the top 10 and was traded a year later for a third- and fifth-round pick, in part, because I like to ask, ‘Why?’

Marcus Mariota: I remember that time I was a good person, which was framed as softness and a lack of competitive fire, eventually leading me to get picked behind Jameis Winston.

Kyler Murray: Well, I’m extremely good at both baseball and football, and had a hard time picking between those two sports since I love them both a lot. That led to some jumbled opinion about how, I guess, then, I didn’t love either sport enough, and so I’m a bad person? If I didn’t get drafted No. 1, who knows where I’d have landed.

Eli: Yeah, I hear you. My parents decided that the Chargers were a bad team so, in a series of seemingly below-board meetings, we made our preferences clear to San Diego and the commissioner that we would not play for them if selected, uprooting the rest of the draft to serve my own personal best interests.

Group: Wow, what happened to you? God, you must have been eaten alive.

Eli: Oh, I went No. 1 anyway but got traded to the Giants so it all worked out fine. The next morning, Stephen A. Smith wrote in the Philadelphia Inquirer that I made the right call. The headline in the Houston Chronicle was “Manning survives difficult weekend.”

Group: *Collective mouths agape*

It’s sort of like the times your parents tried to solve a nuclear-level problem in your life by telling you a didactic little tale from their own past in which a much less significant problem was solved by working hard and being honest, and the whole time you’re sitting there thinking, “Holy hell, they have no idea that everything is much worse now!” Or, in Manning’s case, they would relay a raucous story from their youth, and you’d imagine how 100 percent impossible it would be to get away with now.

The story still comes up every now and then around draft time. Former Chargers GM A.J. Smith recently said that trading Eli was the “most satisfying moment” of his career. But it's a wonder this isn't a more talked-about part of Eli's much-debated legacy.

Imagine if Lamar Jackson and his mom decided they didn’t want to play for the Ravens. Imagine if Kyler Murray had decided he didn’t want to play for the Cardinals. Imagine if Josh Rosen had decided he didn’t want to play for the Cardinals. Imagine if Baker Mayfield decided he didn’t want to play for the Browns. They’d all have a pretty good argument to make. And they’d all be destroyed.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com. We are also accepting Bad Takes from our readers. If you've got one, feel free to write it up and send it in for possible publication.

Conor Orr is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated, where he covers the NFL and cohosts the MMQB Podcast. Orr has been covering the NFL for more than a decade and is a member of the Pro Football Writers of America. His work has been published in The Best American Sports Writing book series and he previously worked for The Newark Star-Ledger and NFL Media. Orr is an avid runner and youth sports coach who lives in New Jersey with his wife, two children and a loving terrier named Ernie.

Follow ConorOrr