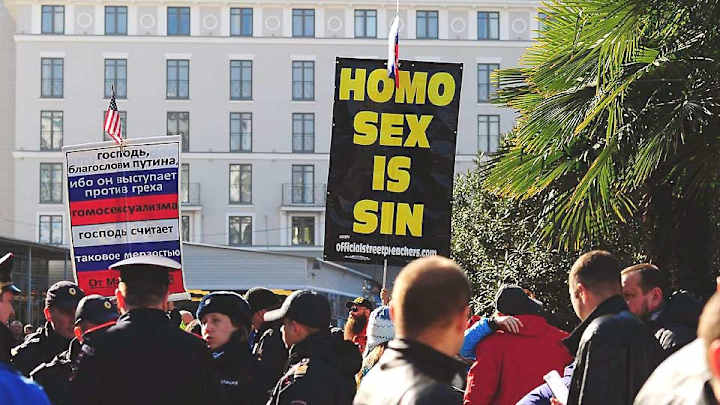

Anti-gay demonstration reveals double-standard in Sochi

SOCHI -- The protest was tiny by any global, urban standard. But the sentiment of the pair of men holding the signs was unmistakably loud.

On a promenade in front of this city’s main railway station, one man held a placard, written in Russian and topped with an American flag, that read, GOD BLESS PUTIN BECAUSE HE IS AGAINST THE SIN OF SODOMY AND GOD BELIEVES IT IS DISGUSTING. Another raised a sign in English, this one surmounted by a Russian flag, with four boldfaced words: HOMO SEX IS SIN.

Protests in and around these Olympic Winter Games are supposed to be confined to a designated zone in the town of Khosta, miles from both downtown Sochi and the Olympic coastal suburb of Adler, and even there only with a permit. Yet under the warmth of the midday sun, with the opening ceremony only hours away, a knot of security guards watched idly nearby.

Apparently, a demonstration in favor of a policy of president Vladimir Putin and his government may proceed with impunity. Never mind that Russia’s recently passed law that bans “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations” is supposed to protect children, and any little Yuri or Tania happening by might have easily been moved to ask, “Mama, what’s sodomy?”

“That’s pretty ironic,” said former U.S. Olympic diver David Pichler, who is gay, upon learning of the protest. Russia’s new law, and the rise in reported harassment of gays in Russia since its passage, had moved Pilcher to travel to Sochi with a delegation from the U.S.-based organization Human Rights First. Concerned by what might happen after the spotlight of attention swings away once the Olympics are over, they’re meeting with LGBT leaders in Russia to offer their support and help plan strategy.

A day earlier the group met with activists in St. Petersburg, where today one of them, Anastassia Smirnova, was among four people arrested for unfurling a banner with the words of Principle Six of the Olympic Charter, which denounces discrimination of all types.

Pichler came to Sochi with an offer to speak with athletes who might want reassurance about what it means to compete as gay Olympians. “I’d extend myself to the IOC or the USOC, if there are any athletes in fear of being open about themselves, just to have someone to talk to,” he says. He is also in town in solidarity with a closeted gay Russian friend -- an Olympic gold medalist -- as well as to keep current Olympians, gay and straight, from having to take up a cause unrelated to their medal quests.

“I want to take that burden off them,” says Pichler, who captained the U.S. diving team in Sydney. “Performing well, that’s their primary purpose. Me, I just want to be safe.”

Shawn Gaylord, the LGBT advocacy counsel for Human Rights First, isn’t aware of any specific athlete protest in the works. “But my guess is that something will happen, and it won’t be punished,” he says, noting that IOC president Thomas Bach has clarified that Principle Six indeed is intended to condemn discrimination against gays, even if the clause doesn’t specifically mention them. And Gaylord believes it’s more likely that a protest would come from a straight sympathizer than an LGBT Olympian -- someone, for instance, like U.S. figure skater Ashley Wagner, who has already indicated that she’ll look for an opportunity to use the Games to speak out.

When Sochi mayor Anatoly Pakhomov said last month that no gay people live in his city, one citizen wrote a letter to a local paper to say that he was gay and offered to meet with the mayor to enlighten him. Indeed, Sochi has at least two gay clubs, and Pichler and Gaylord have plans to meet that letter writer tomorrow at one of them, Mayak (“The Lighthouse”).

But after hearing of what happened today in one of the city’s most public places, with officials apparently giving it their sanction, Pichler has developed second thoughts.

“It gives you pause,” he says. “To know that there’s been anti-gay activity there, it makes you not want to go.”

Senior writer and author Alex Wolff, the longest-tenured writer on staff, has traveled to six continents to cover everything from the Tour de France and the World Series to the Olympics and the intersection of society and sports.