Retirement of Nick Symmonds and Ashton Eaton will leave a void in U.S. track and field

It’s a fundamental truth of American track and field that new stars come along. In this country, track is a sport without a large-scale development system, except that which is generously supplied by high schools (where the sport thrives) and colleges (not as much, but fine). At the same time, there are many other pathways beckoning for talented athletes. Yet the sport here continually replenishes itself enough to put U.S. athletes at the top of the medal table every two years at the world championships and every four years at the Olympics. Track and field is riven with international doping scandals and domestic infighting and woefully inadequate at providing income for all but its very best performers, yet one generation of medalists always replaces the one that came before. It is truly a small miracle and not likely to change anytime soon.

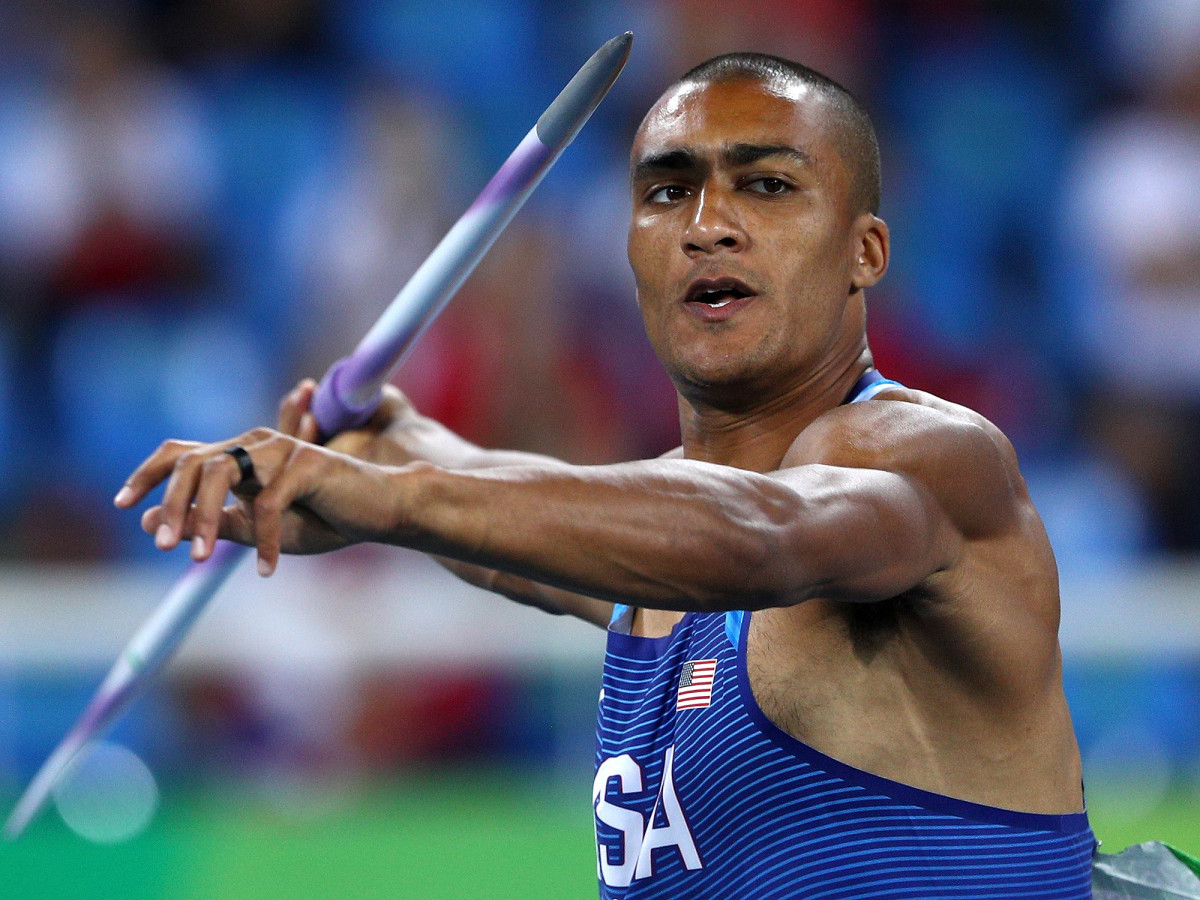

This week, however, two American track and field athletes announced their retirements, and neither will be easily replaced. On Tuesday Nick Symmonds, 33, the fourth-fastest U.S. 800-meter runner in history and an athletes-rights pioneer, declared that he will drag his dodgy left ankle through one more professional season before calling it quits. A day later, two-time Olympic decathlon gold medalist and world record holder Ashton Eaton, 28, retired, effective immediately. (Eaton’s wife, 2015 heptathlon silver medalist Brianne Theisen-Eaton, also retired at the same time). Their departures will leave gaping holes in the sport, although for different reasons.

And this is appropriate, because they were very different athletes, and spokesmen.

Symmonds, who exploded into a cult hero with his (sort of) hometown victory in the 800 meters at the 2008 Olympic Trials in Eugene, ran as if trying to beat races into submission. He was—and still is—barrel-chested, thick-legged and jacked, looking more like the former high school wrestler he once was. “I weigh 165 pounds,” he said to me and Jere Longman of The New York Times in an interview last summer. “This body was not made for running the way I have.” The first laps of his 800s always looked like torture, his upper body swiveling from side to side and his knees driving as he tried to generate enough speed to stay close to the leaders, yet also stay relaxed. If world record holder David Rudisha of Kenya runs like a doe shaken from the forest, Symmonds is a bison rumbling on the open plain—running incongruously fast. But in the final 200, Symmonds was transformed. Driving his arms and lowering his head, he would transition into a full sprint, mowing down the smoother runners who led him around the track, grimacing as if it hurt fiercely, which it did. Every mediocre wannabe middle-distance runner who had known the anaerobic agony of the 800 could feel a kinship with Symmonds. Few men in history have run the distance faster (32, to be exact), fewer still have made it look more difficult.

In the long view, Symmonds will be better remembered for other, more important things (keep reading). But he was a very good runner. He won six national championships, including a second victory at the Olympic Trials, in 2012. Symmonds took fifth place behind Rudisha’s ethereal world record 800 at the London Olympics (and one place behind countryman Duane Solomon), still the fastest—and greatest—top-to-bottom almost-half-mile in history. Symmonds finished in 1:42.95 that day. For perspective, the great Alberto Juantorena never ran that fast. A year later, Symmonds took the silver medal at the worlds in Moscow. It’s inarguable that he is one of the best American 800-meter runners in history and easily one of the appealing.

Athletically, Eaton is nearly the opposite of Symmonds. He made the decathlon, a very difficult undertaking, look... not as difficult. You thought I was going to write easy, didn’t you? Nobody makes the decathlon look easy. There’s no human constructed in such a way as to contest all 10 events of the decathlon without looking awkward in some of them. Big men high-jumping, smaller men throwing the shot. It’s a strange collection of events, some of which are just ill-suited to certain athletes. Bruce (now Caitlyn) Jenner ran the 1,500 meters like Symmonds runs the 800, but Jenner was great at the 1,500 meters. Former world record holder and 1996 Olympic champ Dan O’Brien hardly ran the 1,500 at all.

Eaton looked like he belonged in every one of the decathlon’s 10 events. (Okay, I’ll give you the shot put. Nobody looks like they belong in a shot put ring, except actual shot putters. But even there, Eaton looked less out of place than most great decathletes.) There was a grace to everything that Eaton did. He was a world class long jumper and 110-meter hurdler (and also in the non-decathlon 400-meter hurdles, where he ran 48.69 while just dabbling in 2014), yet also ran 4:14.48 in the 1,500, which is unusually fast for an athlete with such explosive speed at the other end of the spectrum. He also did freaky things, like this. (Thanks to House of Run’s Kevin Sully for the vine.)

Eaton twice broke the world record, first at the 2012 Trials in Eugene (where he ran that 4:14) and again three years later at the worlds in Beijing. He competed with a calm dignity that masked the punishing truth of his event. He made his work look as natural as Symmonds made his look unnatural. It’s a quadrennial parlor game for media to toss out the phrase “World’s Greatest Athlete” and question whether it should be applied to a decathlete. It’s an absurd debate. Here’s what Eaton has been: The greatest decathlete in history. That’s enough. (And let’s acknowledge two other people: Eaton’s wife, who was first his girlfriend when they met at the University of Oregon, and who was also his training partner every day. Both worked under the tireless Harry Marra, a brilliant and dedicated coach and one of the kindest people in the sport. It has been a remarkable team.)

When Symmonds and Eaton walked off the track, they were also manifestly different.

In 2012, Symmonds began aggressively challenging the economic structure of his sport, in particular the rules that limit a track and field athlete’s marketing opportunities and the stranglehold of shoe companies, most pointedly Nike. He auctioned off advertising space on his shoulder for $11,000 (the winning bid was submitted by a Midwest advertising agency). In 2015, he was excluded from the U.S. team for the world championships in Beijing because he refused to sign a document mandating that he “…wear the Nike Team USA apparel …. at all team functions throughout the trip, including at the athlete hotel, during training, press conferences, competition, and award ceremonies. Accordingly, please pack ONLY Team USA, Nike or non-branded apparel….”

Symmonds didn’t sign. When I talked to him at the time, Symmonds said that at the 2014 world indoor championships in Poland, he had been “bullied by several different Team USA staff members for something as simple as having a cup of coffee in my Brooks gear.” (That was pure Symmonds and pure activism: Making his point forcefully and claiming to have been bullied, when anybody who has met Symmonds knows that he is not the sort of person who can be bullied. But good for him. The force of the message was always important.) Symmonds was at the time—and still is—sponsored by Brooks. He wanted to wear his Brooks gear outside the stadium and away from official functions. “Brooks is investing in me,” Symmonds said at the time. “I need to give them a return on that investment at every opportunity when I’m not at an official function.”

Last year Symmonds’s company, Run Gum, which makes a caffeinated gum for athletes, sued the United Stated Olympic Committee for violation of antitrust laws. The goal of the lawsuit was to give athletes the opportunity to advertise products other than shoe companies on their uniforms and bodies, which is currently prohibited, limiting athletes’ earning power. The lawsuit was dismissed in federal court and Symmonds has appealed.

But the larger picture is important. In a sport that has been ruled by bureaucrats and shoe companies that have successfully suppressed athletes’ earning power and voices, Symmonds became the most forceful agitator since Steve Prefontaine was raging at the AAU four decades earlier.

Eaton’s public posture was far more measured and far less iconoclastic. Symmonds would barge into the media mixed zone after races, his pulse still racing, and toss off uninterrupted 1,000-word answers to the any and all questions, whether about his race or the state of track and field politics. Eaton customarily did his mixed zone interviews with a bearing of almost regal elegance, as if he had considered every possible question and every possible answer beforehand. He was always under control, much as he was in competition, and rarely veered into controversy.

But make no mistake: Eaton could be publicly fearless, too. Last year, when I was reporting a story on Jenner, I sought interviews with many modern-era decathletes. Few responded. Some that did were clearly uncomfortable in discussing Jenner’s transition. Eaton did not hesitate. “The transition, that took a lot of courage,” Eaton told me. “She seems happy now.” He even used the correct pronoun, and without hesitation. Eaton lived a complicated life, raised by a single mother in Bend, Ore. He was mature at a young age. One of his half brothers was awarded the Silver Star for his service with the Marines in Afghanistan in 2011, and Eaton attended the ceremony in Washington. He understands the world beyond his professional borders.

He could also be whimsical. When I first interviewed him in 2012, I tossed him a question about lessening the pressure of the Games “by not making it all bigger than it is.” (A lousy question, by the way). He responded: “People only say that about things that actually really are big, right?’’ Right. This week Eaton told Jim Caple of ESPN.com that he wants to be the first person on Mars. Which is funny—but sure, why not?

To the central point here: Not all track and field athletes are replaceable. Symmonds has not been the only voice challenging the system. Distance runner Lauren Fleshman, sprinter Lauryn Williams and shot putter Adam Nelson have all been vocal advocates for atheltes’ rights, but all are retired from active completion. And Symmonds has been the most strident and most willing to place his career and earnings at risk. There is not another Symmonds on the horizon, and that is an enormous loss.

The United States has usually managed to find The Next Great Decathlete. There was Bob Mathias and then Milt Campbell and then Rafer Johnson and then Bill Toomey and then Jenner and then…. A 20-year gap to O’Brien and then a dozen more years to Bryan Clay, the 2008 Olympic gold medalist. (And in the decathlon, there once actually was a national development program, long discontinued). Eaton was the best of them all. He is an act not easily followed.

Track rolls on; it is truly too big to disappear. But today it is a just a little quieter than it was last week, one important voice stilled and one transcendent athlete gone.