World Cup Countdown: 8 Days to Go - What if Antonio Rattín Hadn’t Been Sent Off?

Every team that wins the World Cup needs a bit of luck along the way, and England undoubtedly had their fair share in 1966. There’s Geoff Hurst’s second goal in the final for a start; the heart says it was over the line, but the head’s not so sure.

Then there was the lenient refereeing that hampered the prospects of Brazil and Hungary; skilful sides that could have caused the hosts a world of problems had more brutal teams not been allowed to halt them in their tracks. The English were also fortunate to have their quarter-final against Argentina officiated by Rudolf Kreitlein; a German who wasn’t prepared to tolerate dissent, even if it was expressed in a language that he couldn’t understand. Just as surely as fortune shines on the winners, it abandons losers. And one of those it truly forsook in 1966 was Antonio Rattín, the luckless captain of Argentina.

6⃣6⃣ DAYS TO THE @FIFAWorldCup

— GOLAZO (@golazoargentino) April 9, 2018

Antonio Rattín's controversial sending off against England saw @Argentina go out in the quarter-finals of the 1966 World Cup but did lead to the creation of yellow & red cards. pic.twitter.com/d54Hmcy3Hq

Rattín was not just the leader of his side, he was its creative hub; a classic pivot who patrolled the centre of the pitch, deflecting trouble and initiating attacks. He led an Argentinian side of which much was expected at the World Cup. Two years previously they had competed in the four-team Nations Cup in Brazil; a gathering of some of the finest international teams in the world.

The Argentinians opened with a 2-0 victory over Eusébio’s Portugal, demolished Pelé’s Brazil 3-0 (on their own turf, no less) and then beat England by a goal to nil. Three matches, three wins; six goals scored, and none conceded. On their day, this Argentinian side was a match for anyone. In addition to Rattín they could also boast of Luis Artime, a prolific striker; Ermindo Onega, a playmaker in whose steps Kempes, Maradona and Riquelme would follow, and Silvio Marzolini, an attacking left-back who so frightened Ramsey that he brought Alan Ball back into the team for the quarter-final, just to counter his threat.

Argentina were not one of the four seeded teams in the first round and ended up being drawn into a tough group alongside West Germany, Spain and Switzerland. Their first game was against a talented Spanish side which featured a host of Real Madrid players that had won the European Cup a couple of months earlier. They were no match for the skilful Argentinians, however, who ran out winners by two goals to one.

Next up were the Germans, and this time the bellicose side of the Argentinian team showed its face; Albrecht was sent off and the entire team was subsequently censured by FIFA’s disciplinary committee for its conduct. It was an ugly game and, fittingly, it ended goalless. Argentina then went on to defeat Switzerland 2-0 in their final group game but West Germany, who had beaten the Swiss by more, topped the group, leaving the runners-up to face the hosts at Wembley.

Two nervous teams walked out onto the pitch that sunny Saturday afternoon, both acutely aware that the other was more than capable of ending their World Cup dreams. The England players had watched the Argentinians play West Germany and so knew what to expect, both good and ill.

The game started well for the hosts, who dominated possession and fashioned some half-chances. The visitors then asserted their own spell of pressure before England moved into the ascendency once more. This normal ebb and flow was then disrupted as the incident for which this game is infamous suddenly erupted.

#OnThisDay in 1966 @Argentina were knocked out of the World Cup by @England at Wembley after Antonio Rattín's controversial red card pic.twitter.com/OMCRo47pwC

— GOLAZO (@golazoargentino) July 23, 2017

Rattín had been a thorn in the referee’s side since the start of the game, following him around the pitch, persistently offering his opinions and protesting at his decisions. Kreitlein had cautioned Rattín a few minutes earlier for an attempted trip on Bobby Charlton, and his patience with the Argentine captain then evidently snapped as his judgement was questioned once more. Rattín, to his complete amazement, was ordered off, in only the 36th minute of the game, with Kreitlein presumably hoping that would be the end of the matter. Only it wasn’t.

Rattín refused to leave the pitch and eight minutes of fierce debate followed in which the Argentine captain, his manager and teammates all attempted to persuade the referee to change his mind. Which, of course, he wouldn’t.

Rattín eventually made the long walk back to the tunnel, but what had already been a fairly fractious encounter now inevitably became much more bad tempered. The English players later accused their opponents of kicking, spitting and punching, while the Argentinians contended that the hosts had hardly behaved like angels themselves.

1966 #FOTD Antonio Rattín became the first player to be sent off at Wembley in a controversial & fierce quarter final match against England pic.twitter.com/pq8nbWuu5Q

— Football:On This Day (@footyonthisday) July 23, 2017

The visitors were playing defensively enough when they had eleven men on the pitch, but with only ten they retreated even further; the game settling into a pattern of England trying, and failing, to make a dent in the Argentine rearguard. When the Argentinians did get the ball, they passed it around among themselves, rarely threatening the England goal. Their evident aim was to survive until the end of extra-time and then surrender their fortune to the coin-toss that would have followed.

Penalty shoot-outs had not yet been devised as a way of determining the result of a game that ended in stalemate, the outcome being entrusted instead to the capriciousness of a coin-toss. In these days of VAR, it seems almost incomprehensible that the outcome of such an important game could be decided this way, but the use of a coin toss was not uncommon at the time.

A year earlier, Liverpool had reached the semi-finals of the European Cup because of their captain’s ability to call tails rather than heads. Both legs of their quarter-final tie against Cologne had ended goalless and the two sides still couldn’t be separated after a play-off in neutral Rotterdam.

Farcically, even the coin toss was not decisive initially, with the referee’s first effort ending in deadlock when the coin landed on its edge in the mud. Then, in 1968, it was the turn of the Italians to benefit from Fortuna’s fickleness; Giacinto Facchetti correctly calling tails after their European Championships semi-final against the USSR had ended goalless.

Thankfully, Rudolf Kreitlein never needed to dig a pfennig from out of his pocket, with Geoff Hurst’s headed goal thirteen minutes from the end of normal time settling the encounter in England’s favour. The drama didn’t end there, however.

1966: Argentina captain Antonio Rattin is sent off during the Quarter Final against England. pic.twitter.com/ZwITMHR75E

— World Cup Photos (@WorldCupPhotos1) March 7, 2014

If the incident involving Rattín wasn’t incendiary enough, Alf Ramsey then made matters even worse by refusing to let his players swap shirts with their adversaries at the end of the game. He subsequently went on to label them as ‘animals’, thus single-handedly doing more damage to Anglo-Argentine relations than anyone else prior to the outbreak of the Falklands War.

Perhaps if Rattín had simply got on with the game, rather than spending his time badgering the referee, Argentina could have beaten England or, at the very least, taken them all the way to the lottery of a coin toss. Perhaps if that had happened, instead of becoming a knight of the realm, Ramsey would have remained plain Alf; a forlorn figure forever bemoaning his captain’s inability to call tails.

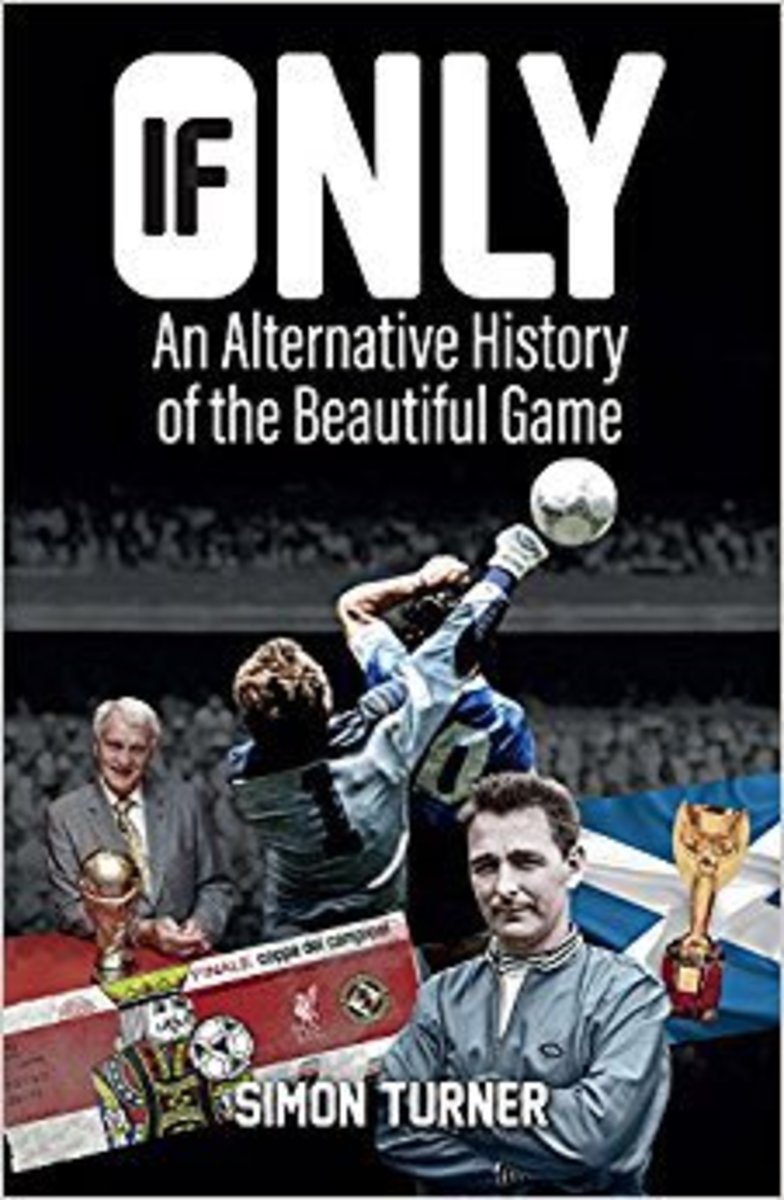

Simon Turner is the author of ‘If Only: An Alternative History of the Beautiful Game’ published by Pitch Publishing. You can follow him on Twitter at @simonaturner100