No Wave is Insignificant: Surfing camp with the Paskowitz clan

This story originally appeared in the August 19, 1996 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

It's 6 a.m. on a Saturday, and Dorian Paskowitz is wide awake. A sinewy, deeply tanned man who has dedicated most of his adult life to surfing, the 75-year-old Paskowitz checks the gear loaded onto one of two 1965-vintage campers. Satisfied with the configuration of the loads, he calls to one of his sons to "wake the kids and get the show on the road." Then he watches as his instructions are carried out. Within minutes, two thirtysomething men and five teenagers stumble bleary-eyed out of their tents and into the campers.

The convoy journeys a mile down the San Diego Freeway to San Onofre State Beach, where the "kids" wolf down breakfast, change into wet suits, grab their surfboards and plunge into the Pacific Ocean. Paskowitz settles into a beach chair, picks up a pair of well-worn binoculars and lets out a sigh. At 7 a.m. it's shaping up to be another perfect day in paradise.

Sports Illustrated's greatest surfing photography

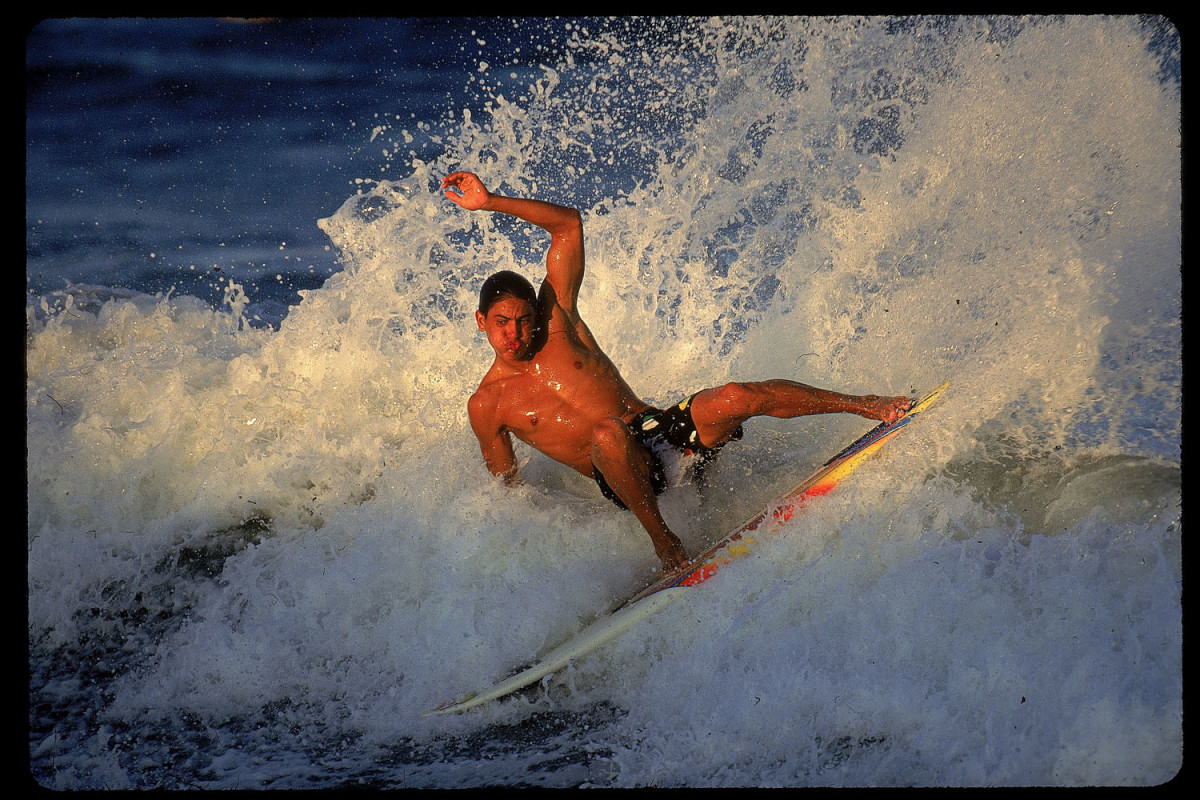

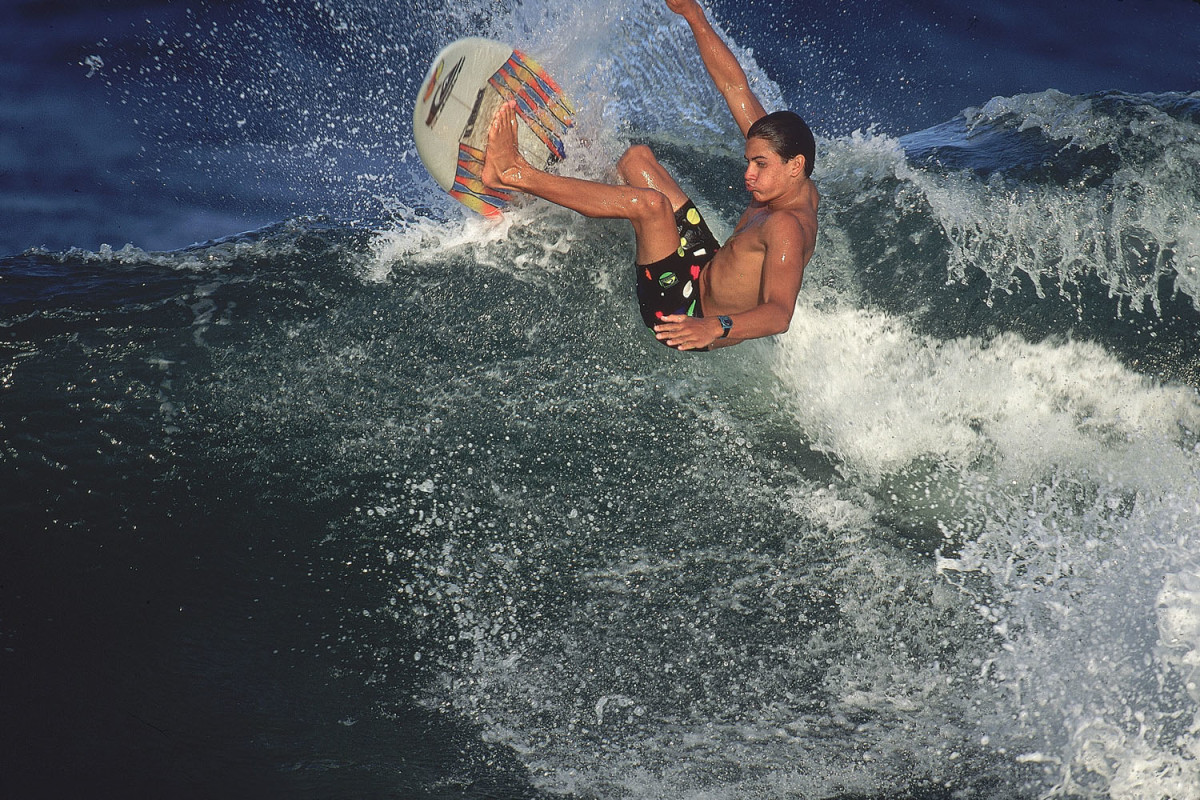

Adam Scott

Rocky Point Surfers

Big Surf at The Wedge

Big Surf at The Wedge

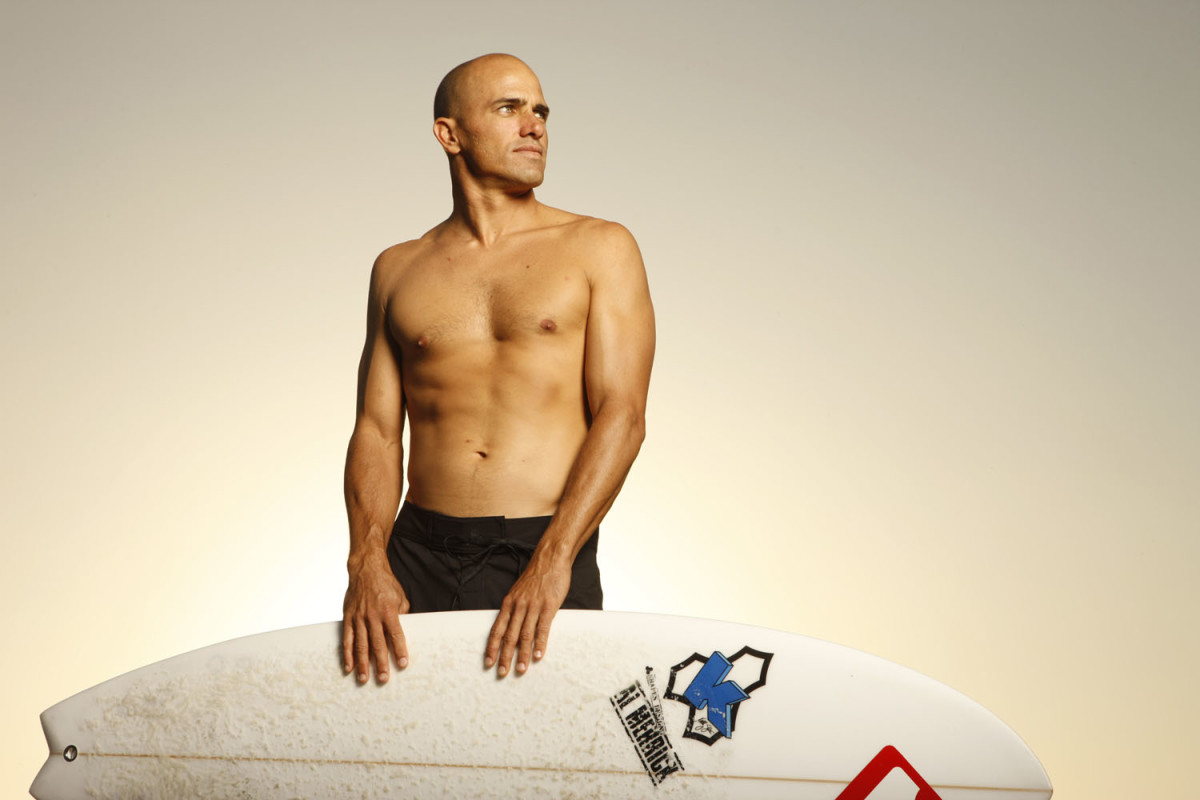

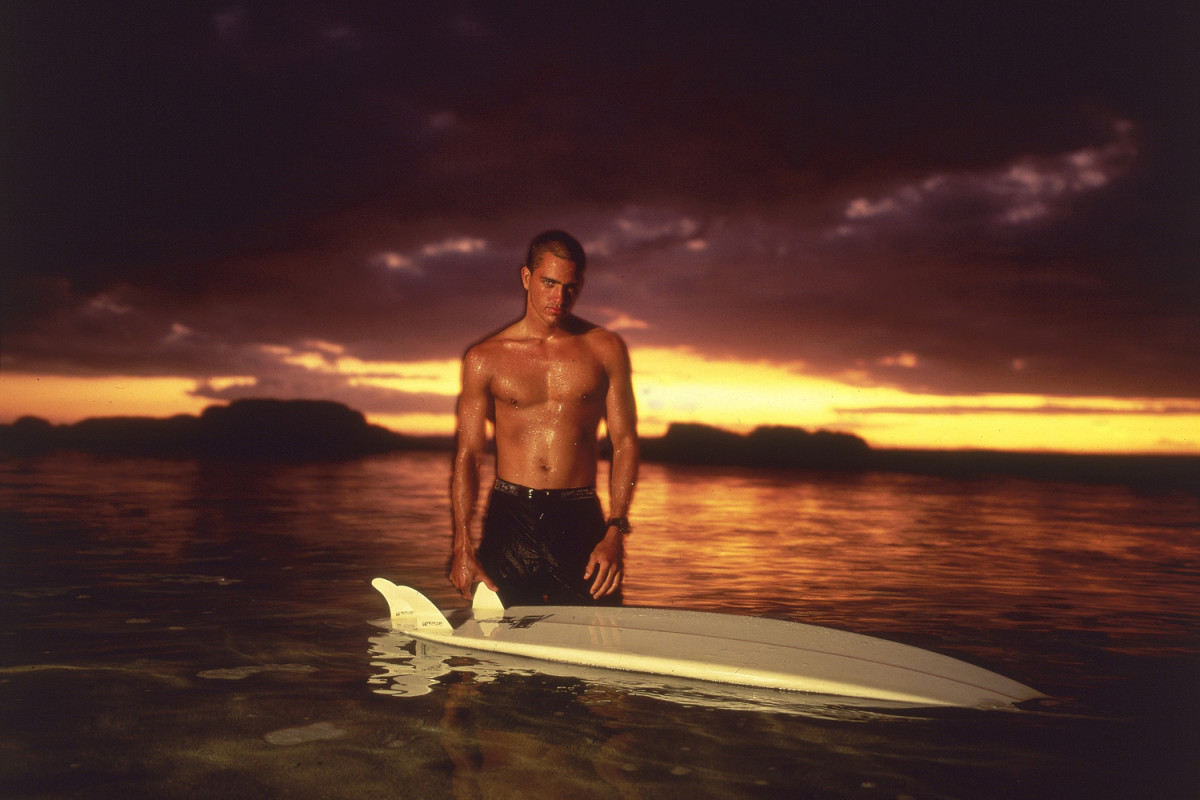

Kelly Slater

Big Surf at The Wedge

Surfing the Waimea Shorebreak

Surfing the Waimea Shorebreak

Surfing the Waimea Shorebreak

Billabong Girls Pro Maui

Kellen Ellison

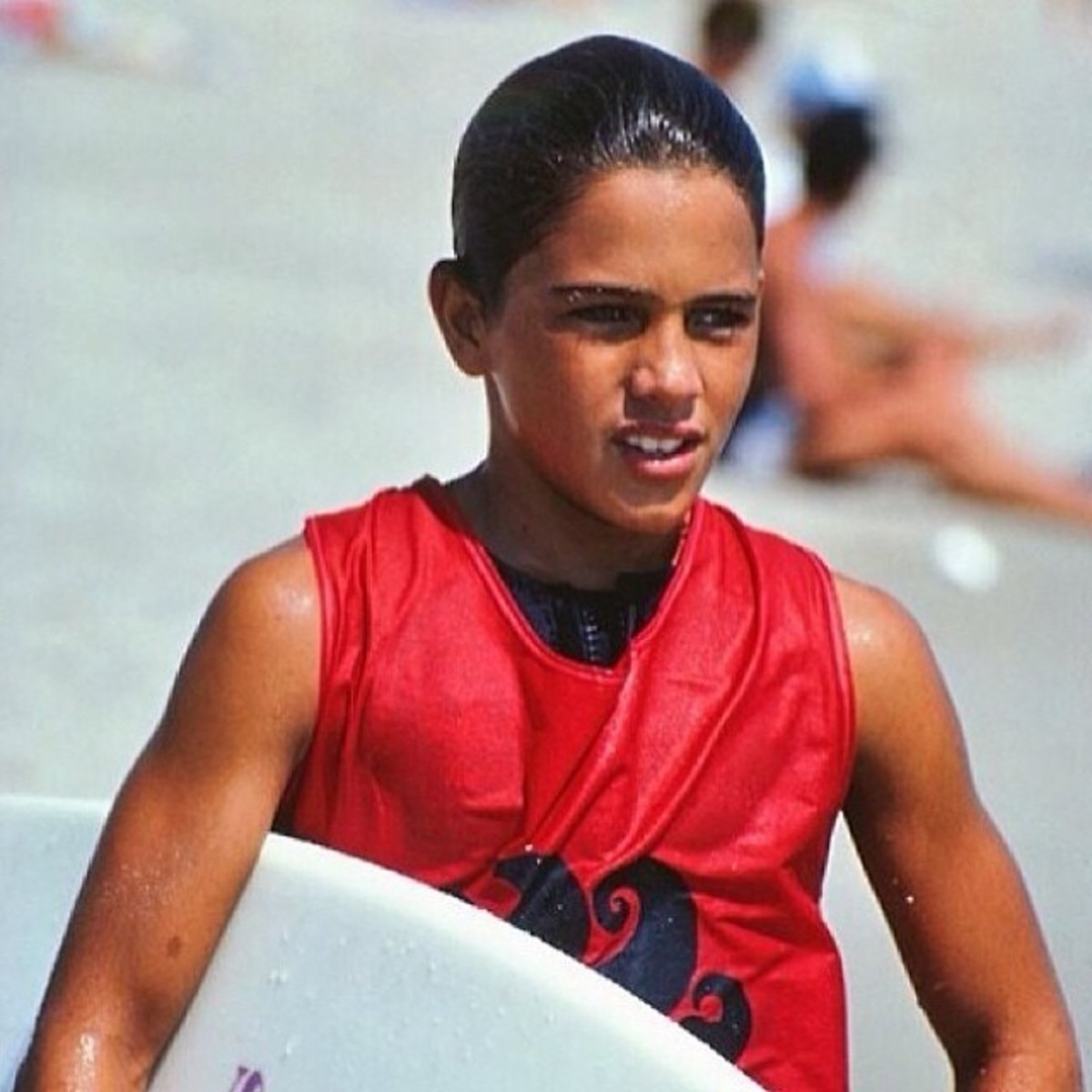

Kelly Slater

Pipeline Masters

Kyle Turle

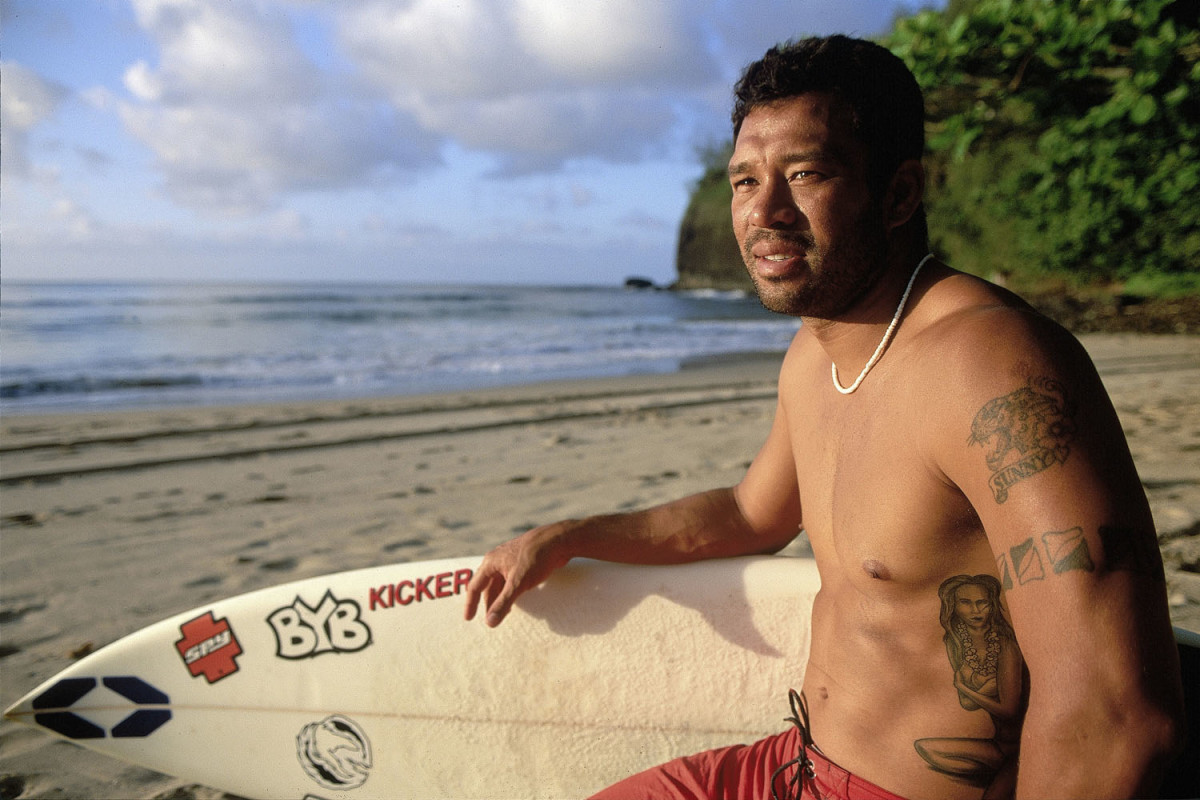

Sunny Garcia

Kelly Slater

Laird Hamilton

Vibe Tribe: (From left to right) Mike Organista, Ryan Moore, Shaun Organista, Spencer Davis, Naomi Bralver, Steve Johnson, Zach Moore, Lisa Luna, Jeff Boyd, and Matt Moore.

Laird Hamilton, Bruce Irons, and Andy Irons

Carissa Moore

Adam Scott

Kelly Slater

Kelly Slater

Kelly Slater

Julia Mancuso

Rocky Point Surfers

Andrea Johnson

Billabong Girls Pro Maui

2014 VANS U.S. Open of Surfing

Kelly Slater wins his 50th ASP tour victory

Kelly Slater wins his 50th ASP tour victory

Mavericks Invitational

Mavericks Invitational

Mavericks Invitational

Mavericks Invitational

Mavericks Invitational

Lakey Peterson

Lakey Peterson

Double trouble.

In Southern California, where the sun shines early and often, and the waves curl beachward in gently precise tubes, summer days were invented for surfing. Since 1972, the Paskowitz family--Dorian; his wife, Julieta; their sons, David, Jonathan, Abraham, Israel, Moses, Adam, Salvador and Joshua; and their daughter, Navah--has run this surfing camp near San Clemente, a beach town about 70 miles north of San Diego that is best known as the site of the Nixon "summer" White House. But locally San Clemente is known as the home of the first family of surfing, which teaches campers everything from how to stand up on a board to how to catch waves and how to master the ever-changing forms of "surfer-dude" speak.

The coed camp, which is for "people age nine to 90," according to the Paskowitzes, lasts one week, and there are usually eight sessions per summer. Mornings and afternoons are spent surfing at a spot called Old Man's Break, but there is plenty of time in between to eat, doze and relax, and during the week there is a foray into San Clemente to visit local surf shops. At night campers sleep in tents at San Mateo State Park, where the Paskowitzes rig up a VCR so that everyone can watch surfing and/or horror videos before passing out from exhaustion. The cost is $840 per week--meals, snacks, campsite fees and surfing equipment included.

Most of the enrollees in this particular session are novices, such as Matt Garrison, 32, a corporate lawyer who has come out from New York City. "In the times that I've caught waves on a boogie board, the feeling is like nothing else," says Garrison, sitting on the back of a camper on the first day of instruction.

"Not only are you moving, but what you're moving on is also moving."

Another novice, Robert Schwartz, 13, enrolled for two consecutive weeks to get in maximum practice time. "I skateboard and I snowboard, but I live in Tucson, and there aren't many waves," he says. "I'm hoping to stand up on a board and learn to do a few turns."

On the first morning Israel Paskowitz, 33, a former national longboard champ, teaches the camp's most basic lesson: the "1-2-3" method of standing up on a board. This involves 1) lying flat on the board, hands gripping the sides; 2) raising the upper body; and 3) jumping up to the erect surfing position, feet apart and knees bent in a boxerlike stance. After demonstrating the technique on land, Israel leads his students into the ocean and lets them rip.

"It takes about 10 minutes to get a leash on them and put them into the water," says David Paskowitz, 37. "We just sit back and say, 'Well, are you happy?' And they say, 'Dude, I'm stoked.'"

The story of the Paskowitz clan has taken on mythic proportions in the surfing community, and with reason. Dorian, who moved to Southern California from Galveston, Texas, in the mid-1930s, graduated from Stanford Medical School in 1945. He says he attempted to live a "normal" life, but surfing, and the pursuit of the perfect wave, ultimately prevailed.

In 1956 he walked into what he remembers as a "very wicked bar" on Catalina Island. There he met Julieta Emilia Paez, a 6'2" contralto who would soon become his third wife. "I thought she was Tahitian, but it turns out she was Mexican-American," says Dorian with a laugh. "I fell in love."

Strange Rumblings: The search for the perfect wave

Dorian persuaded Julieta to surf the world with him. Together they traveled through Mexico and the U.S., then journeyed to Israel, Egypt, Lebanon, Spain and the South Seas. They schooled all nine of their children at home. When the family needed money, Dorian would find part-time work at clinics and hospitals that treated low-income patients.

David, the oldest child, remembers that "at age six and seven, we used to quiz each other on the Physicians' Desk Reference. We would spend hours with novels: Not one word was spoken, because we were all in our individual books."

As Israel recalls, "Most of growing up was great. Traveling the world and the adventures we had were amazing. But I don't like remembering everything, like watching my dad write a bad check so we could eat. That was scary for a young kid."

As he watched his children grow up and begin to leave the nest, Dorian came up with the idea for the camp. "I wanted my kids next to me, enjoying the summer," he says.

Twenty-five years later, that's exactly what the camp is—an opportunity to enjoy a summer week with the Paskowitzes, who teach a lot about surfing and camping and a little about life. "We take our campers and incorporate them into the lifestyle that we live," says David. "We treat them as part of our family."

Bill Greenwood, an anesthesiologist from Key West, has been coming to the camp with his daughter Kristin, now 20, for the last 11 years. "Learning to surf in a family atmosphere makes the camp different," says Bill. "The campers all get caught up in this extended family, so young kids don't feel out of place, older people don't feel out of place, and women don't feel out of place."

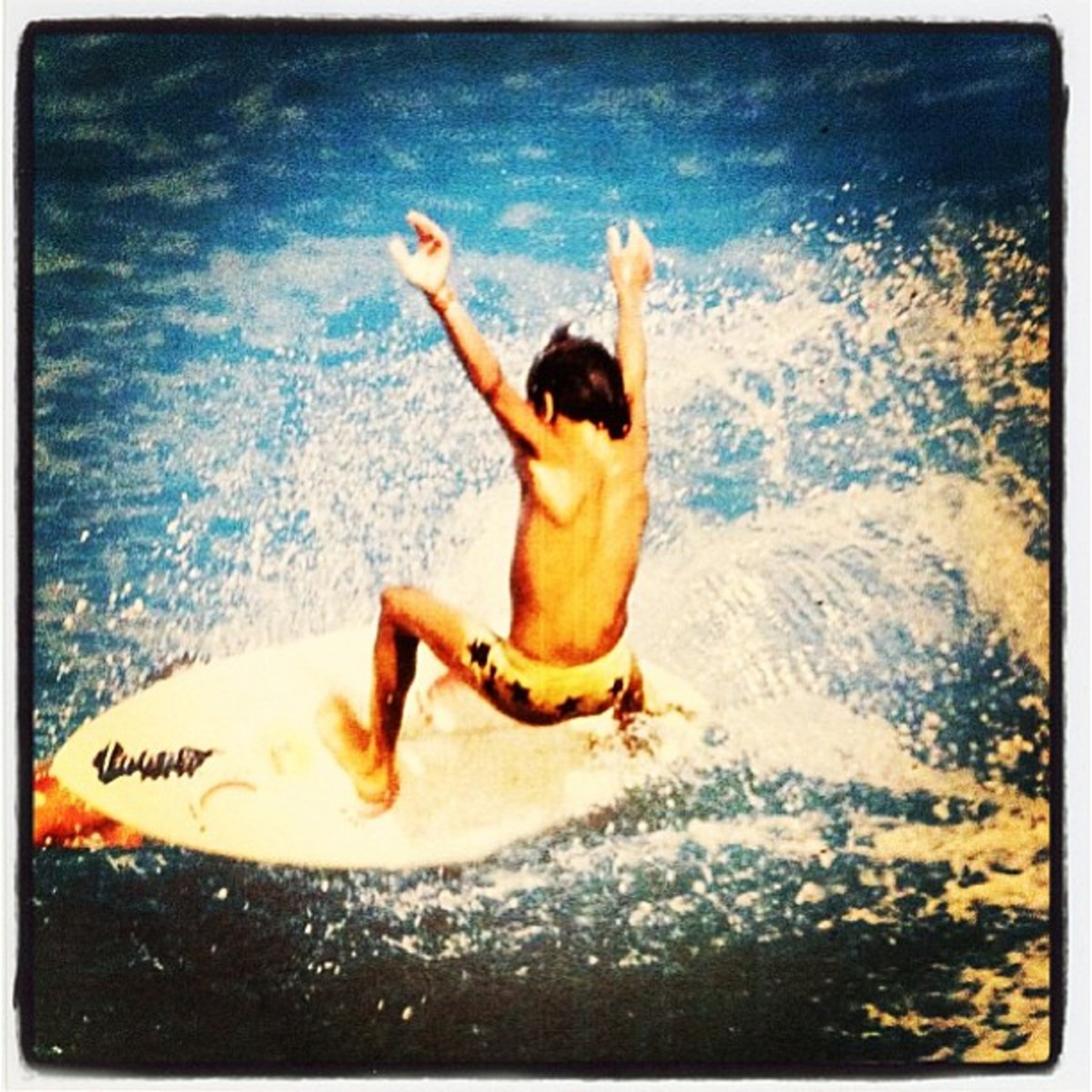

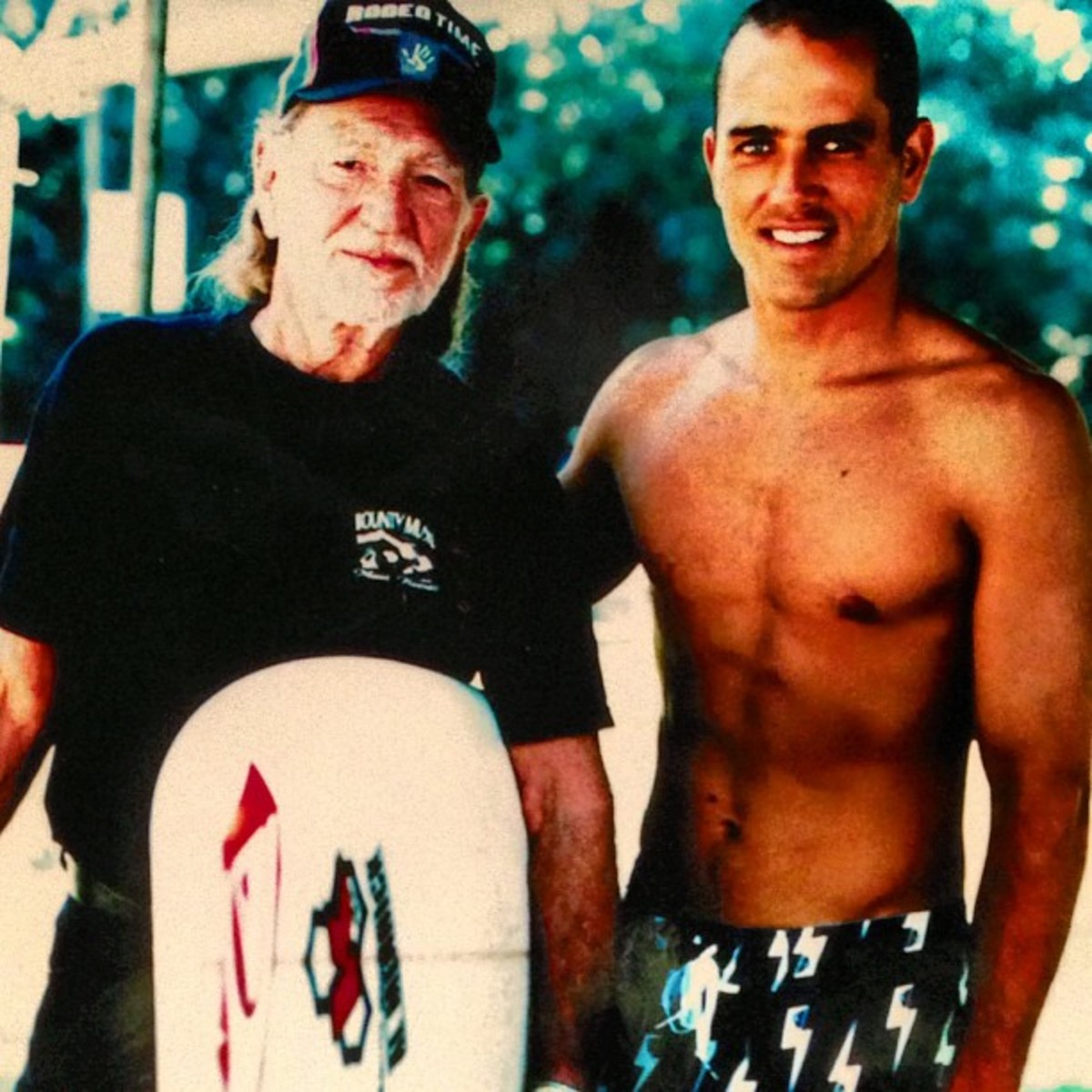

A Day in the Life: Professional surfer Kelly Slater

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

Kelly Slater’s impact on the sport of surfing is unparalleled. He claimed the ASP World Tour title at the age of 21, including a run of consecutive titles between 1994-1998, and in 2007 became the all-time leader in career events won. Follow Slater on Instagram @kellyslater.

"It's great," says Garrison, proudly displaying a scraped knee. "You get a lot of time in the water with people who not only know how to surf but know how to teach people to surf."

Robert Schwartz, meanwhile, is already planning what he wants to accomplish during his second week. "My goal is to do more tricks," he says. "I want to learn how to turn and how to get up faster on the board. Once I learn to stand up faster, I can catch the wave a bit longer, and I can catch different types of waves."

When the summer-camp season is over, Dorian and Julieta head south to spend the winter months in their camper in Baja California, Mexico's most western state. Their children, with their children in tow, occasionally journey south to visit. No longer a wandering tribe, the second generation of Paskowitzes has settled down: David, 27-year-old Adam and 21-year-old Joshua are rock musicians; Jonathan, 35, is an executive with Black Flys, a fashion-sunglasses company; Israel surfs competitively and makes his own line of surfboards, called Izzy; Abraham, 34, is an international sales manager for Jaisel, a clothing company; Moses, 32, is a transportation manager for the Teamsters; Salvador, 29, owns a graphic business that provides art designs for surfwear companies; and Navah, 27, is a part-time model for Guess? sportswear.

The children still listen closely when their father speaks about surfing and life. To Dorian, who tries to catch a wave every day, surfing is all about the allure of the cosmic wave. "A wave is the end result of vast quantities of energy striking upon the surface of the sea, pushing it down in one place, thereby making it rise up in another place," he says. "The waves that you see here start out in Antarctica at about 80 feet. By the time they get here, they're the most well-fashioned, beautifully sculpted things in the world. And when you hook yourself to this enormous atmospheric energy that's so cosmic and so vast, something in that primordial beginning washes off onto you, and you become a part of it."

Camp dismissed.