As good as Bobby Jones? Yes, she was, and then some

There was a time when two of golf’s greats met head to head, which isn’t unusual at all, but here’s the twist: one was a man, the other a woman. One was from the United States, the other from England. They played from the men’s tees, straight up, with no strokes given nor asked for. Together, the two dominated golf in the 1920s.

They were Bobby Jones and Joyce Wethered.

Jones’ record in national championships is well known. He won four U.S. Opens, three British Opens, five U.S. Amateurs and one British Amateur. Jones had the advantage of playing on five Walker Cup teams, which gave him the opportunity to play golf in Great Britain.

Joyce Wethered is less well known in the U.S., but she won the English Ladies Championship six times, including five in a row, and was victorious in the British Ladies Championship four times. Wethered never played tournament golf in the U.S. The major event for female golfers at the time was the U.S. Women’s Amateur, and two weeks’ travel time by sea would have been required to play in a single event. She would have come to America to play had the Curtis Cup been established during her active career.

Jones and Wethered knew each other during their competitive careers. Wethered’s older brother, Roger, who taught her the game, was an excellent golfer in his own right, winning the 1923 British Amateur and playing in five Walker Cup matches, where he lost twice to Jones in singles.

Joyce Wethered first saw Jones play in the 1923 Walker Cup at St. Andrews. She also followed Jones when he shot 66 and 68 at Sunningdale in qualifying for the 1926 British Open and then at the tournament itself at Royal Lytham & St. Annes, when Jones won the first of his three Claret Jugs. When she first saw Jones play, Wethered altered her swing to a slightly more upright plane to emulate his action.

At a time when many top golfers remained amateurs, contestants returned to events regularly, and many friendships were formed. Jones became close with both Wethered siblings.

The name Joyce Wethered might not be familiar to many golfers because her play was in the increasingly distant past and she didn’t get the press coverage in the U.S. to put her at the forefront of women’s golf. Wethered won her first notable event 100 years ago at age 18 when she came out of nowhere to defeat the dominant female golfer of the day, Cecil Leitch, 2 and 1, to take the 1920 English Ladies Championship.

Wethered stood 5 feet 10 inches and was slender, but she packed a punch on the course. She had everything for a championship golfer: an elegant sense of balance, a graceful swing, length off the tee, good iron play and a deadly putting stroke. In addition to her driving distance, she hit it straight. As England’s Henry Cotton, a three-time British Open champion, noted of Wethered, “I do not think a golf ball has ever been hit, except perhaps by Harry Vardon, with such a straight flight.”

In 1925, Wethered was plowing through the field at the British Ladies at Troon and met the 1922 U.S. Women’s Amateur champion, Glenna Collett, in the semifinals. Collett also was a three-time winner of the Women’s North and South and the Women’s Eastern Amateur and a two-time winner of the Canadian Women's Amateur. It was the match British golfers were longing for: the best American female against Britain’s best. The gallery swelled to 5,000. It was a tough match, but Wethered was level fours through the 15th hole, ultimately winning, 4 and 3.

Bernard Darwin, the golf correspondent for The Times of London newspaper, offered great praise for Wethered, writing, “I hereby declare that more flawless golf than Miss Wethered’s has never been played by anybody, man or woman, or demi-god. It would be easy to write pages about her, but the real story is this: that she twice took three putts on the green in the first nine holes. Apart from that there was not a single shot that one could criticize…. It was magnificent, supremely magnificent, but hardly golf as ordinary persons understand the word.”

Wethered and Collett would meet again in the final of the British Ladies Championship in 1929. Wethered was 5 down in the match but fought back to win, 3 and 1. Collett never was able to beat Wethered in a head-to-head match.

Henry Cotton was impressed and stated that Wethered’s game was strong enough for her to be selected for the Walker Cup team had she not been a woman.

Before the 1930 British Amateur at St. Andrews, Wethered partnered with Bobby Jones in a four-ball match against her brother and T.A. Bourn, a noted amateur, over the Old Course. It was a windy day, with a good breeze off the North Sea. Wethered played from the men’s tees. Although Jones knew the Old Course well, he found himself three strokes down to Wethered through 15 holes. She three-putted the last two holes for a 76. Jones squeaked in ahead of her with a 75.

Afterwards, Jones said, “I have not played golf with anyone, man or woman, amateur or professional, who made me feel so utterly outclassed. It was not so much the score she made as the way she made it. It was impossible to expect that Miss Wethered would ever miss a shot — and she never did.”

A few days later, Jones would go on to win the 1930 British Amateur over the Old Course, the first leg of his Grand Slam, defeating Roger Wethered in the final, 7 and 6.

Jones retired from competitive golf after his 1930 Grand Slam, and Joyce Wethered also retired from tournament golf after winning the 1929 British Ladies Championship; neither had any worlds left to conquer. But the two would meet again in a match a few years later.

The Great Depression of the 1930s hit hard, and the Wethered family did not escape economic difficulties. In 1934, Joyce Wethered took a job at London’s Fortnum & Mason department store, in its sporting goods section. The British golfing community felt a bit awkward with her decision to work there, and the R&A revoked her amateur status. If she’d worked in any other part of the store, she would have been spared, but the authorities determined that Fortnum & Mason was using her golfing abilities to sell golf equipment and clothing.

However, this detour brought Wethered back to golf, this time playing exhibitions for money in the U.S. and Canada.

Fortnum & Mason hooked up with the John Wanamaker Department Store in Philadelphia to arrange a series of matches over a period of nine weeks in 1935. The matches ended up stretching beyond three months, covering 15 states and three Canadian provinces. Wethered played 53 matches and set 34 women’s course records.

She was to be paid $200 per match, plus 40 percent of the gate after expenses. It is estimated that she earned $20,000 for her whirlwind tour, and some believe the figure to be much higher. She also received her regular Fortnum & Mason salary, and all travel expenses were paid. If the $20,000 seems small compared to what top female golfers can earn today, consider that $200 in 1935 is equal to about $3,800 in 2020. For $3.50, one could stay in a top hotel, and $10 would buy a nice set of golf clubs. Wethered found a good bargain in the middle of the Depression.

The Wanamaker Department Store advertised its women’s sportswear lines heavily in the American press, with clippings highlighting Wethered’s play in the exhibitions.

Her first match was scheduled for May 30 at the National Women’s Golf & Tennis Club on Long Island. She was paired with her former rival, who since had married and become known as Glenna Collett Vare, to play against Gene Sarazen and Bobby Jones. However, due to appendicitis, Jones had to drop out, and he was replaced by Johnny Dawson. Later, with 12 matches played in the East, she would meet up with Jones on June 18, at his home course, East Lake Golf Club in Atlanta.

Sportswriter George Trevor watched Joyce in her first exhibition and wrote in The Sportsman, “Genius is a disquieting thing. It defies analysis, cannot be translated into words. That graceful fluid swing epitomized the effortlessness of art. Even tyros in the gallery, realized, perhaps subconsciously, that here visualized in the flesh, was a living picture of everything the textbooks and theorists had written about the perfect golf swing.”

Wethered was operating under several handicaps during her North American tour. She played every course “blind”; there were no practice rounds, so each course was new to her. She also had caddies who didn’t know her game and, in the U.S., she had to play the larger American ball rather than the smaller British ball, which she preferred. However, for her play in Canada, Wethered had to switch back to the British ball. She proved to be highly adaptable in dealing with these conditions.

When Wethered arrived in Georgia, she faced another problem: Bermudagrass greens. She’d never putted on Bermudagrass, which had been likened by British professional Ted Ray as putting on gnarled grapevines in comparison with the slick bentgrass greens in the U.K. But she picked up on the new conditions quickly.

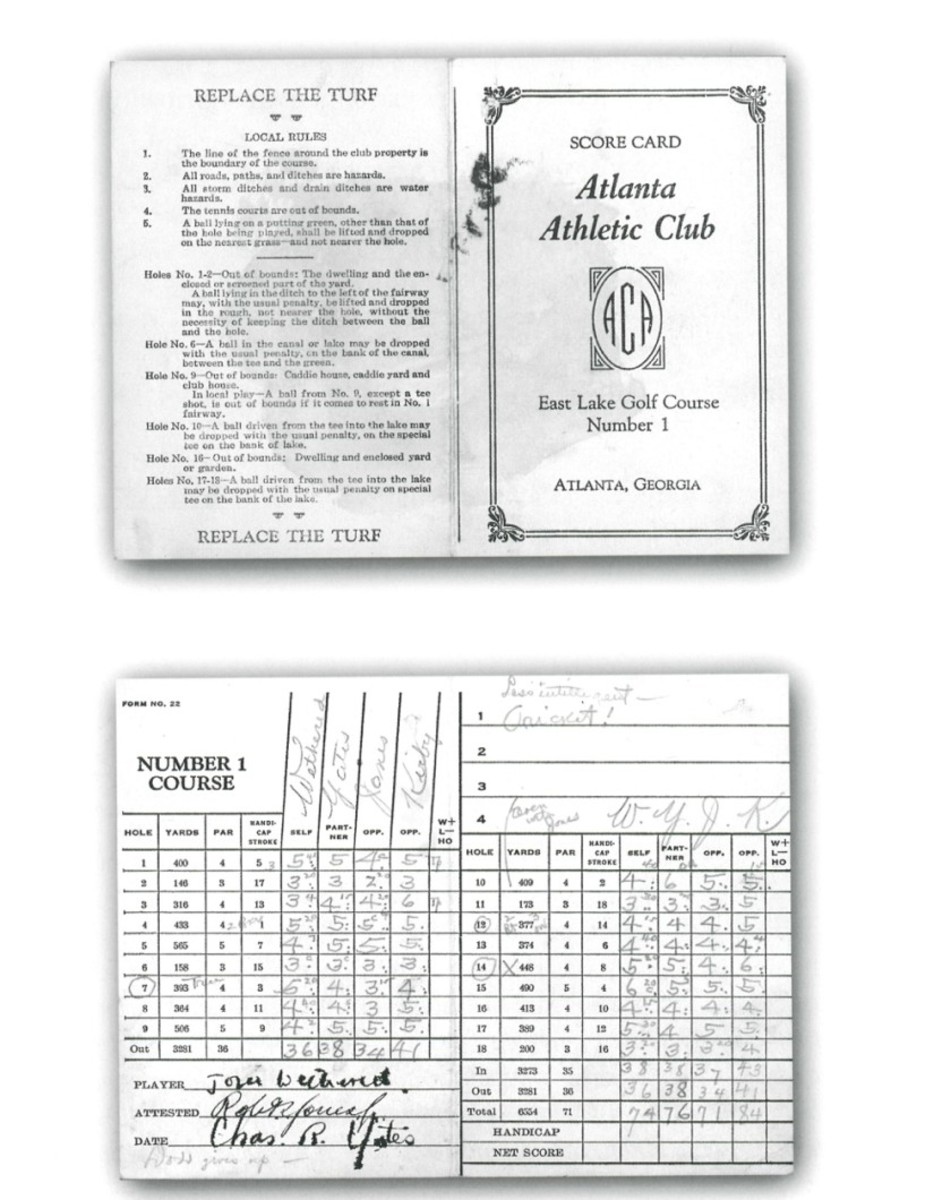

At East Lake, she was paired with Charlie Yates, the reigning NCAA champion who would go on to win the Western Amateur, the British Amateur and play on two Walker Cup teams. Jones paired with 14-year-old Dorothy Kirby, who was the Georgia state women’s champion and later won the U.S. Women’s Amateur.

The match was hard-fought and ended up being halved after Jones dropped an 18-foot putt for a par on the 18th hole. Wethered’s play didn’t disappoint. O.B. Keeler, the sportswriter for the Atlanta Journal who covered golf and had seen Jones win all 13 of his major championships, was taken aback by her game, writing, “In sheer power, Miss Wethered’s game was bewildering. From the 14th tee, as a sudden half-gale came to blow full against the drives, she discharged a low, raking shot that ended up beyond the beautifully struck tee shots of Jones and Yates.”

As for the new Bermudagrass greens, Wethered had two three-putts and five one-putts.

As her partner, Yates was in awe of Wethered’s game. “First time I ever played 14 holes as a lady’s partner before I figured in the match,” Yates said. “She was carrying me around on her back, and all I could do was try not to let my feet drag. I reckon I would have been pretty embarrassed. I was sort of hypnotized watching her play.”

There was a good-sized gallery watching the match at $1.50 per head, and betting was heavy before the match that Wethered wouldn’t break 80. She shot 74, tying the women’s course record previously set by Atlanta’s Alexa Sterling. Jones shot 71, Yates posted 76 and Kirby had an 84.

The match had accomplished what Jones wanted from it: an opportunity for his fellow Georgians to see the great British star play in person. Jones entered the hospital the following day for an appendectomy finally to resolve the problem which had kept him from playing Wethered in her first American appearance.

Wethered left the next morning by train for Cincinnati and a transfer to Pittsburgh for a match at Oakmont. It would be this way for her, hopping from city to city to play exhibitions, finally ending Sept. 15 in Montreal, where she teamed up to win her last North American match, at Marlborough Golf Club.

Wethered returned to work at Fortnum & Mason and played golf with friends. In 1937, she met Sir John Heathcoat-Amory playing golf at Westward Ho! in Devon, England. They soon were married, and she became Joyce, Lady Heathcoat-Amory. They lived on his estate, Knightshayes in Tiverton, Devon, and developed nationally recognized gardens.

She continued to play “friendly” golf. When asked whether she still played to win, she responded, “Do I play to win? But, of course. You do, don’t you?”

In 1954, Wethered was elected as president of the Ladies’ Golf Union, and her amateur status was reinstated by the R&A.

Wethered died in 1997, one day after her 96th birthday, leaving behind a legendary career demonstrating she could play with the best of golfers, male or female, which helped to promote women’s golf in Great Britain and North America.

Sign up to receive the Morning Read newsletter, along with Where To Golf Next and The Equipment Insider.