For Marlins, fire sales and cynicism in South Florida are nothing new

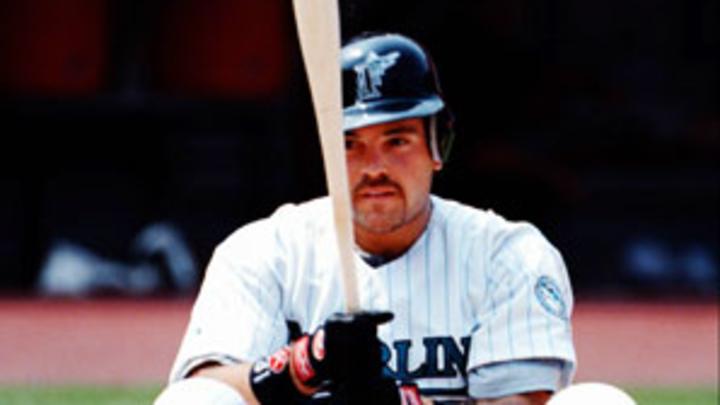

Mike Piazza spent one week as a Marlin in 1998 and was part of two megatrades in the team's first fire sale. (AP)

After committing $191 million to a trio of free agents last winter, nearly doubling their payroll in anticipation of the opening of their new ballpark and bringing in a manager who was louder and more offensive than their new orange jerseys, the Marlins didn't waste much time in knocking down the house of cards they'd built. Prior to the July 31 deadline, with Miami sinking under .500 and more than 10 games back in the NL East standings, it unloadedHanley Ramirez, Anibal Sanchez, Omar Infante and several others in five separate trades. In October, the Marlins dumpedHeath Bell, the least successful of those pricey free agents, and on Tuesday night, they sent both Jose Reyes and Mark Buehrle, the other two, to Toronto as part of a 12-player blockbuster that also cost them ace Josh Johnson, starting catcher John Buck and outfielder Emilio Bonifacio.

Alas, this isn't the first time the franchise has dramatically slashed payroll and shed a slew of productive players in a short period of time. But where the popular perception is that the Marlins conducted fire sales in the immediate aftermath of their shocking World Series victories in 1997 and 2003 and then rose from the ashes to contend again, the reality is much messier. For all of the cynicism with which the team has conducted its business, the shrewd swapping of general managers Dave Dombrowski (1993-early 2002) and Larry Beinfest (since then, though with a variety of titles) stands out, as it has enabled the team to return to contender status despite owner Jeffrey Loria's slash-and-burn style.

Perhaps it shouldn't surprise us, given that the Marlins were conceived in cynicism in the first place. They entered the National League in 1993 along with the Colorado Rockies as part of a cynical ploy by the other 26 owners to raise cash to help offset the $280 million settlement the owners agreed to pay the players for colluding to avoid competitive bidding on free agents in the winters following the 1985, 1986 and 1987 seasons. Wayne Huizenga, the Marlins' first owner, paid a $95 million expansion fee for the franchise.

The team was well under .500 for its first three seasons, two of which were interrupted by the 1994-1995 players' strike, but even so, it had begun assembling a nucleus of good players around whom it could build, such as rightfielder Gary Sheffield, leftfielder Jeff Conine, catcher Charles Johnson and closer Robb Nen. In the winter following the 1995 season, the Marlins bolstered their rotation by signing both Kevin Brown and Al Leiter, and added centerfielder Devon White as well. In the following winter, they added starter Alex Fernandez, leftfielder Moises Alou and third baseman Bobby Bonilla, who reunited with incoming manager Jim Leyland, for whom he had starred with the Pirates.

The additions didn't come cheap, relatively speaking. Florida's Opening Day payroll in 1995 ranked 25th out of 28 teams at $23.7 million in 1995, but jumped to 15th at $30.1 million the following year (a 27 percent increase), and then to seventh at $47.8 million for 1997 (a 58 percent increase). Augmented by rookie middle infielders Edgar Renteria and Craig Counsell — acquired mid-season from the Rockies — the pricey team jelled, winning 92 games and the NL wild card, then knocking off the Giants, Braves and Indians en route to a world championship.

But the champagne had barely dried when Dombrowski began stripping the roster, less for parts than to pare payroll. Fifteen days after Renteria drove in Counsell with the World Series-winning run, Alou was traded to the Astros for a trio of players, none of whom amounted to a hill of beans. By the end of the month, Nen, White, Conine and lefty reliever Ed Vosberg were sent to the Giants, Diamondbacks (a just-formed expansion team), Royals and Padres for more players who similarly amounted to nothing, and likewise for December deals of reliever Dennis Cook (Mets) and infielder Kurt Abbott (A's). The trade of Brown to the Padres did bring back a three-player package that included 22-year-old first baseman Derrek Lee, and likewise, the February trade of Leiter to the Mets fetched a three-player package that included starter A.J. Burnett.

The world champions weren't entirely gutted, but they were well on their way. They opened the season with a $33.4 million payroll (back down to 20th out of 30, a drop of 30 percent), and by May 13, they were 13-27. The next day, Dombrowski sent Sheffield, Bonilla, Johnson and two other players to the Dodgers in exchange for Mike Piazza and Todd Zeile. Eight days later, he flipped Piazza to the Mets for three players, including outfielder Preston Wilson and pitcher Ed Yarnall; late that summer, Zeile would be traded to the Rangers for two minor leaguers who never panned out. After the season — a 54-108 debacle — Leyland resigned, and Dombrowsi traded the 22-year-old Renteria to the Cardinals for a trio of players including Braden Looper and Pablo Ozuna. Yarnall left as part of a three-player package sent to the Yankees for third base prospect Mike Lowell.

Fast-forward to February 2002, when Bud Selig greenlighted a complex franchise swap that allowed Marlins owner John Henry (who had bought the team from Huizenga in January 1999) to purchase the Red Sox and Loria, who owned the Expos, to acquire the Marlins, with the Expos turned into wards of the other 29 teams; they would eventually move to Washington in 2005. Dombrowski departed for Detroit, and Loria hired Beinfest. The team went 79-83 season with a $42.0 million payroll (25th out of 30) in its first season under the new regime, following which Beinfest traded Wilson, Johnson (who had returned via free agency), Ozuna and Vic Darensbourg to Colorado for Juan Pierre and Mike Hampton. The Marlins then flipped Hampton to the Braves, assuming some $30 million in salary while freeing themselves from the suddenly burdensome contracts of Johnson (to whom they had signed a five-year, $35 million deal in December 2000) and Wilson (to whom they had signed a five-year, $35 million extension). In January, they signed Ivan Rodriguez to a one-year, $10 million deal.

With Pierre their leadoff man, Lee and Lowell their top two power hitters, and Rodriguez their backstop, the Marlins had a strong core, augmented by the homegrown middle infield of Luis Castillo and Alex Gonzalez, and an outstanding young rotation that owed to the work of their two smart GMs. Josh Beckett was taken with the number two pick of the 1999 draft after the 1998 team had tanked, Brad Penny had come in a 1999 trade with the Diamondbacks for Matt Mantei, Dontrelle Willis (recalled in May to replace the injured Burnett) was acquired via a six-player March 2002 trade with the Cubs that sent away Matt Clement, and Carl Pavano was brought in thanks to a mid-2002 deal with the Expos for Cliff Floyd. The 2003 squad left the gate with a payroll of just $48.8 million (25th out of 30), struggled early, and ditched manager Jeff Torborg in favor of Jack McKeon. In June Florida called up 20-year-old slugger Miguel Cabrera, in July it traded 2000 overall No. 1 pick Adrian Gonzalez to the Rangers for Ugueth Urbina, who would supplant Looper as the team's closer, and at the Aug. 31 deadline, it reacquired Conine from the Orioles in exchange for two minor leaguers. The Marlins finished 91-71, winning the NL wild card, and went on to upset the Yankees in the World Series for their second championship.

The ensuing teardown wasn't immediate, though Rodriguez, Urbina and Looper were among those who departed as free agents, and Lee was traded to the Cubs in a deal that brought back first baseman Hee-Seop Choi. Beinfest cut payroll to $42.1 million (still 25th), and while the Marlins dipped to 83-79, they remained competitive; their most notable free agent was closer Armando Benitez, while their most notable in-season deal sent Penny and Choi to the Dodgers in exchange for Juan Encarnacion, Paul Lo Duca and Guillermo Mota, all proven commodities with considerable (but not outrageous) salaries. Pavano left as a free agent following the 2004 season, as did Benitez, but Leiter returned via an $8 million deal, and slugger Carlos Delgado signed a heavily backloaded, four-year, $52 million contract that paid just $4 million in its first season. With their young core mostly still in place, payroll climbed to $60.4 million (19th), and while the team was again respectable at 83-79, Loria's negotiations with Miami-Dade County for a new ballpark broke down late that year. To punish the fans who continued to stay away in droves — the team ranked 15th in the NL in attendance that year, the seventh out of eight in which they remained in the league's bottom three — Loria instructed Beinfest to tear the roster down.

Burnett, Encarnacion, Gonzalez and Conine departed as free agents, as did several lesser players. Delgado was traded to the Mets for Mike Jacobs and Yusmeiro Petit. Beckett, Lowell and Mota were sent to the Red Sox for Hanley Ramirez, Anibal Sanchez and two others, Pierre went to the Cubs for Ricky Nolasco and two others, and Castillo (Twins) and Lo Duca (Mets) were swapped for prospects who never came to fruition. When the dust settled, the Marlins had an Opening Day payroll of just $15.0 million — one-quarter of what it had been the previous year. In a study I did for Baseball Prospectus back in February, I found that to be the largest payroll drop in the post-collusion era in terms of percentage, and the second-largest drop in terms of dollars. Including the mid-2005 deal that sent a washed-up Leiter to the Bronx, the Marlins shed their top 13 salaries from the year before.

Securities and Exchange Commission opened an investigation

Jay Jaffe is a contributing baseball writer for SI.com and the author of the upcoming book The Cooperstown Casebook on the Baseball Hall of Fame.