Three Strikes: The myth of October momentum; more thoughts

Fear not, fans of the Astros, Cardinals and Royals: Your contending teams may all be playing worse baseball in September than they did over the previous five months, but a bad September means virtually nothing when it comes to postseason play. That's because the idea of “hot teams” holding the edge when the playoffs begin is a myth.

There have been 20 world champions in the wild card era. Breaking them down by how they played in September relative to how they played otherwise, 11 of them played better and nine played the same or worse—a veritable coin flip of meaning to September.

So how did this idea get started? For the first 65 years of the World Series, momentum did mean something, because the best team in each league typically finished the regular season on Sunday and played Game 1 of the World Series on Wednesday. Championships were decided in something very close to the regular-season rhythm.

As the playoffs expanded, off days and multiple rounds have made September less predictable. Take the Mets, for instance. Like the Blue Jays and Cubs, they are playing better in September than their overall record. But they won’t play Game 1 of the NLDS until Oct. 9—after four days off and 12 days without a meaningful game.

Power Rankings: Blue Jays hold off Cardinals for first place, Mets rise

September baseball has never looked so unlike October baseball as it does today. That’s because teams are calling up and using an increased number of expanded roster players in September, and because of the surfeit of off days in October. The 2013 Red Sox, for instance, won the World Series with as many off days (15) spaced among just their 16 postseason games as they had in their last 100 regular-season games.

“There are four distinctly different periods of managing a baseball team,” said Orioles manager Buck Showalter. “Spring training, the first five months of the regular season, September and the playoffs.”

The modern postseason format favors an experienced, aggressive manager and shutdown relief pitchers—and not necessarily a deep bullpen, because all the off days allow a manager to go to his “winning pieces” in the 'pen earlier and often. The worst quote you could ever hear from a manager after a postseason loss in explaining his strategy is, “That’s how we did it all year.” October is not “all year.”

“Bobby Cox had it right,” Showalter said of the Braves' Hall of Fame manager. “There’s so much riding on every game, even every pitch, in the postseason that it usually pays to be the aggressor. Put the pressure on the other team. Take nothing for granted. It’s a different game.”

• MORE MLB: Full playoff standings, postseason odds, magic numbers

2. How Papelbon got to D.C.

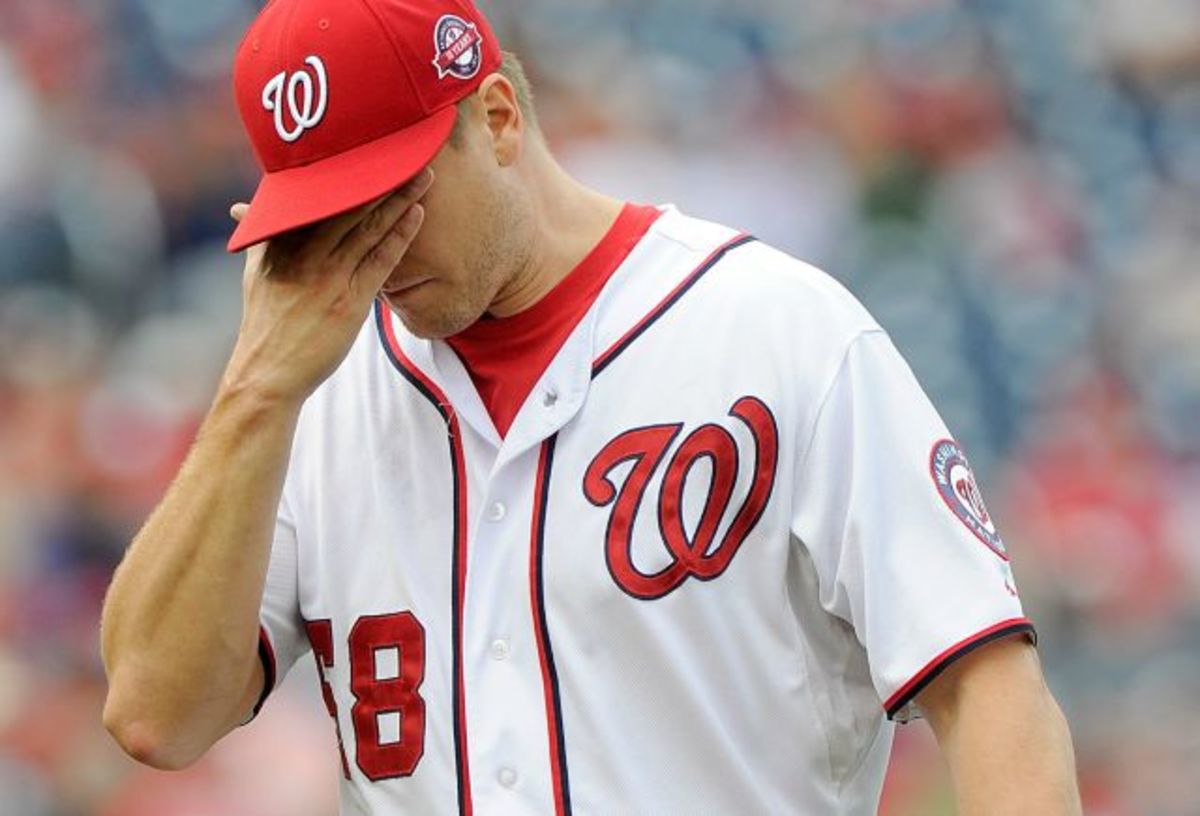

With Jonathan Papelbon twice out of line Sunday—first for calling out Bryce Harper in full public view (from the top step of the dugout), then for escalating a verbal confrontation by shoving Harper by the throat into the back wall of the dugout—it’s worth remembering how Papelbon wound up with the Nationals in the first place.

While the Phillies made Papelbon available at the trade deadline, many clubs backed off the 34-year-old closer because of his contract (he was due up to $17.5 million this year and next) and his reputation for mouthing off. Remember how he began this season: by complaining that in his fourth year in Philadelphia, which had signed him to a $50 million contract after the 2011 season, he had “never been embraced here, from day one.” Club executives with two teams told me they regarded it risky to introduce Papelbon into a team environment at midseason.

Wait 'Til Next Year: Papelbon-Harper drama far from Nationals' only issue

That’s when Papelbon became an option. So eager were the Phillies to move Papelbon that they were willing to pick up the entire $4.5 million owed him this year. (Washington would agree to pick up his 2016 option, though at $11 million instead of the previously agreed upon $13 million.)

Rizzo knew Papelbon’s reputation. This trade wasn’t just about the velocity on his fastball or the command of his splitter.

“We did a lot of due diligence, like we do with every player that we acquire at the trade deadline or the draft or anything,” Rizzo said at a news conference Monday. “We talked to a lot of his teammates, a lot of teammates he had in Boston. He’s one of those guys that maybe irritates you if he’s on the other team. But he’s a good teammate that wants to win. He’s a competitive guy.”

National disgrace: Washington has serious issues to address, and soon

The Nationals were in first place with a two-game lead when Rizzo agreed to trade for Papelbon on July 28. He fit the budget. He would cost nothing to the Nationals in 2015. Nothing? Now Washington has on its 2016 payroll a pitcher with a declining strikeout rate and an $11 million salary who ripped his former team before and after his trade (he said he was one of the few Phillies who cared about winning), who attacked and embarrassed his new team’s franchise player slightly more than five minutes after he arrived in D.C., and to whom the Nationals just handed a please-go-home suspension (a four-game ban that, when tacked onto the three-game suspension he was given for hitting Baltimore's Manny Machado last week, equates to him missing the rest of the regular season).

And coincidentally or not, the closer Papelbon replaced in Washington, Drew Storen, had a 1.64 ERA before the trade and a 7.56 ERA after it. Moreover, Papelbon’s attack on Harper may contribute to Nationals manager Matt Williams losing his job. Already on the hot seat, Williams claimed not to know the severity of the altercation in his own dugout when he sent Papelbon back to the mound in a game tied in the ninth inning. (Papelbon gave up five runs—no doubt running hard while backing up bases.)

Now that teams have stopped overvaluing prospects and bragging about their farm systems as if that were the goal of Major League Baseball, we are seeing more aggressiveness at the trade deadline, regardless of market size. Last year, Oakland stepped up to get starting pitchers Jeff Samardzija and Jon Lester, and Baltimore reached for a two-month rental of reliever Andrew Miller.

This year, the landscape of the postseason was altered at the deadline. Most obviously, Toronto (David Price, Troy Tulowitzki, et al), Kansas City (Johnny Cueto, Ben Zobrist), Texas (Cole Hamels) and the Mets (Clippard, Yoenis Cespedes) became entirely different teams by adding payroll for the final two months. The four best records since the trade deadline belong to the Blue Jays, Mets, Cubs and Rangers.

The lesson is that any team, regardless of market size, better keep some powder dry for what has become an extremely important window in the industry as it relates to team architecture. The Nationals got Papelbon for nothing in 2015. Rarely has a freebie come with such ancillary costs.

• TAYLER: Harper-Papelbon fight is new low in Nationals' horrible season

3. Correa's path to power

Carlos Correa hit 18 home runs in his 229 minor league games entering this year. This year in the major leagues, he has exceeded that total (21) in less than half as many games (93). What happened? On Saturday during our Fox broadcast of the Rangers-Astros game in Houston, I broke down how he has such incredible plate coverage that he has hit home runs on pitches nine inches off the inside corner of the plate and out of the strike zone up and away—while keeping the same balanced lower half to his swing. The key is how he uses his hands and torso, and how Correa taught himself last winter how to hit that pitch close to this body with power.

“In the minors, I wasn’t hitting home runs on balls on my hands,” Correa said. “I would hit the ball with too much top spin or hook spin. I wanted to turn those singles or foul balls into doubles and homers.”

Cardinals inch closer to division title, while Dodgers’ celebration on hold

Here’s what he did: Correa put a baseball on a tee directly in front of his front side as he took his stance—as if a pitch were on a path to hit him. Then he swung at the baseball—not simply to hit it, and not to pull it, but to hit it toward the left-centerfield gap. And he had to do it with a normal stride, not one in which he steps away from the plate. It sounds almost like a physical impossibility. But to do so, Correa had to pull his hands close to his body and rotate his torso earlier and faster in order to get the barrel of the bat squared in time to drive the ball to the gap. Hitting the ball square, rather than “coming around” the ball, eliminates top spin or hook spin. He worked on this drill throughout the winter.

The adjustment has turned Correa, who already profiled as an elite hitter, into one of the most valuable assets in baseball: a 21-year-old who plays in the middle of the diamond and hits in the middle of the lineup with elite power. He is off to an historically prolific start when you consider his youth and position. Correa hit two home runs Saturday, giving him 21 five days after his 21st birthday. Only 16 players ever hit more home runs at such a young age; Correa was tied with Willie Mays for 17th place.

If you look only at shortstops at that age, Correa has hit more home runs than anybody but Alex Rodriguez (29). And his 21 homers in his first 92 games—regardless of age—are far and away the most by any shortstop, blowing past Nomar Garciaparra (14) and Rodriguez and Rico Petrocelli (13). Combine great skills with a tremendous baseball IQ at such a young age, and you can’t help but see greatness ahead.