Breaking down Today's Game Hall of Fame ballot, Part 5: Schuerholz, Steinbrenner

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the 2017 Today’s Game Era Hall of Fame ballot, which will be voted upon by a 16-member committee of writers, executives and Hall of Fame players on Dec. 4 at the Winter Meetings in National Harbor, Md., with the results to be announced that night at 6 p.m. ET. For a detailed introduction to the Today’s Game Era ballot, please see here.

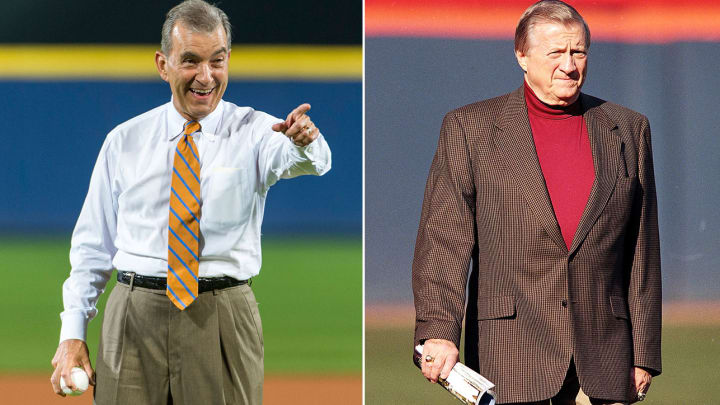

Among the ranks of executives eligible for placement on the Today’s Game Era ballot, it would be tough to find a pair more different than George Steinbrenner and John Schuerholz. Steinbrenner, the Yankees’ principal owner for three and a half decades, embraced the spotlight and transcended the sport to become part of the tapestry of popular culture, hosting Saturday Night Live, starring in commercials and being lampooned on Seinfeld. He also ran afoul of baseball to the point of being suspended not once but twice, and at least for the first half of his career, he fostered instability within his organization and was a sucker for a quick fix. By stark contrast, Schuerholz, a longtime general manager with the Royals and Braves, probably couldn’t have been picked out of a police lineup by all but the most hardcore fans—not that he would ever find himself in one. A model executive, he spent more than a decade in both Kansas City and Atlanta, engineering long competitive runs that relied on homegrown talent and foresight and resulted in championships for both.

If there’s one thing that unites this odd couple, it’s that their teams both won often, and even if they didn’t win it all, the expectation was that they’d contend for a championship every year. That’s what gives both compelling cases for Cooperstown.

John Schuerholz

Few executives have been connected to as much winning baseball as Schuerholz, who cut his teeth with the late 1960s Orioles, was a key part of the Royals' evolution from expansion team to perennial contender and built the Braves into a modern dynasty. In 26 years as a general manager with Kansas City and Atlanta, his teams won 16 division titles and six pennants, and he became the first GM to oversee champions in each league: the 1985 Royals and '95 Braves. Including his time on either side of that run—first in the scouting and player development side with the Royals, then as club president of the Braves (a title he still holds)—his teams have made 24 playoff appearances.

A Baltimore native, Schuerholz went to high school across the street from the Orioles' Memorial Stadium and graduated from Towson University (where he starred in baseball and soccer) with a degree in secondary education. At 26 years old, he was teaching junior high geography and moonlighting for his masters degree at Loyola University when he decided to write a letter to Orioles owner Jerold Hoffberger. He passed the letter on to executive vice president Frank Cashen, a former sportswriter who recognized the family name for their involvement in basketball. Schuerholz interviewed with Cashen, general manager Harry Dalton and director of player development Lou Gorman during the Orioles' 1966 World Series sweep of the Dodgers, and shortly afterward, he was hired as Gorman's administrative assistant.

The Orioles were on their way to becoming a dynasty, winning three straight pennants from 1969 to '71. But when Gorman left to become farm director of the expansion Royals in 1969, Schuerholz followed, becoming the assistant farm director and then—after being wooed by the Yankees, when former Royals GM Cedric Tallis joined their front office—getting the full title in '76, the first year the Royals won the AL West. He continued to climb the organizational ladder as director of scouting and then assistant GM. Fueled by a talent pipeline that produced George Brett, Frank White, Willie Wilson, Dennis Leonard and Dan Quisenberry, the Royals made five postseason appearances in a six-year span, highlighted by their 1980 American League pennant.

Breaking down the Today's Game Hall of Fame ballot, Part 4: Bud Selig

When GM Joe Burke was promoted to club president after the 1981 season, Schuerholz became GM; at 41 years old, he was the youngest in history to that point. The Royals finished above .500 in six of his nine years (1982–90) on the job, winning at least 90 games three times, but only in '84 and '85 did they make the playoffs. Led by homegrown starters Bret Saberhagen and Danny Jackson and with Brett, White, Wilson and Quisenberry as key contributors, Kansas City overcame three-games-to-one deficits in both the ALCS (against the Blue Jays) and World Series (against the cross-state Cardinals) for the franchise's first championship.

Schuerholz's tenure leading the Royals wasn't without its mishaps, including the cocaine suspensions of trade acquisitions Vida Blue and Jerry Martin (along with Wilson and first baseman Willie Mays Aikens), the trade of David Cone to the Mets for catcher Ed Hearn and the free-agent signing of reliever Mark Davis. The 1987 death of Dick Howser (who managed the team from late '81 to mid-'86) from a brain tumor no doubt took its toll, as did a power struggle with Burke and the declining health of owner Ewing Kauffman.

After the 1990 season, Schuerholz departed Kansas City to become the GM of the Braves. He had been rebuffed twice in trying to convince their GM, Bobby Cox, to become the Royals' manager after Howser's death. Cox had already agreed to return to the Atlanta dugout when Braves president Stan Kasten mentioned to Schuerholz that he was looking for a new GM.

The Braves had averaged 96 losses a year during Cox's five-year tenure as GM, but he had amassed the young talent—future Hall of Famers Tom Glavine and John Smoltz, fellow starting pitcher Steve Avery, third baseman Chipper Jones and outfielders David Justice and Ryan Klesko—that would turn the franchise around. With Schuerholz bringing in 1991 NL MVP Terry Pendleton, Sid Bream and other veterans via free agency, the Braves vaulted from 97 losses and a sixth-place finish in 1990 to 94 wins and a pennant in '91. They lost to the Twins in a thrilling seven-game World Series and to the Blue Jays in the 1992 World Series as well, but thanks to Schuerholz's long-term planning, Atlanta was just beginning a remarkable 15-year run atop the NL East, interrupted only by the 1994 strike. After the 1992 season, Schuerholz signed reigning NL Cy Young winner Greg Maddux; from '91 to '98, he, Glavine and Smoltz would claim seven NL Cy Young awards, six as Braves. The next summer, Schuerholz traded three prospects who went nowhere to the Padres for Fred McGriff.

In 1995, the Braves won their first championship since ’57, beating the Indians in the World Series. They dropped both the ’96 and '99 World Series to the Yankees, but Schuerholz kept the team atop the NL East and in the hunt every year as the cast evolved, fueled by additions like homegrown stars Andruw Jones, Rafael Furcal and Marcus Giles and trades for Gary Sheffield, Russ Ortiz and Mike Hampton. That helped Atlanta weather the free-agent departures of Glavine (after the 2002 season) and Maddux (after '03). Not until 2006 did the team slip out of the playoff picture and below .500.

After the 2007 season, Schuerholz was promoted to team president, with Frank Wren taking over GM duties; even with that post-2005 downturn, Schuerholz's Braves won at a major league-best .593 clip during his tenure. After his ascent upstairs, Atlanta returned to the playoffs in 2010, Cox's final season, and again in '12 and '13. But following a disappointing 2014 season, Wren was fired, and the team embarked upon a rebuilding program that's still in progress as it moves into its new Cobb County ballpark.

Breaking down Today's Game Hall of Fame ballot, Part 3: The managers

As I wrote six years ago (just prior to the election of Pat Gillick), the ranks of GMs are underrepresented in Cooperstown, primarily because the position didn't really come into focus until the second half of the 20th century. Among the non-Negro League executives in the Hall, only Ed Barrow, Gillick, Larry MacPhail, Branch Rickey and George Weiss are there primarily for their GM work, sometimes while holding fancier titles. Enshrined managers (Connie Mack and John McGraw), owners (Mack and Bill Veeck, Jr.) and future league presidents (Warren Giles and Lee MacPhail) did time in that capacity as well. From here, Buzzie Bavasi, Bob Howsam, Dalton and Bing Devine are among those for whom solid cases can be made, as they built not only multiple winning teams but also ones that sustained several years of success. Schuerholz certainly belongs in that camp, even given the Braves' failure to win more than one World Series during their epic run. After all, that didn't stop the Expansion Era Committee from electing Cox on the 2014 ballot for his managerial work, and of course, Schuerholz does have his Kansas City credentials as well.

Looking at it another way, authors Mark Armour and Daniel Levitt—who have co-written two SABR award-winning books on team-building and baseball operations, Paths to Glory (2004) and In Pursuit of Pennants (2015)—published a worthwhile series ranking the top 25 GMs of all time in connection with the latter book. They ranked Schuerholz sixth behind Rickey, Gillick, Barrow, Howsam and Weiss, with Armour citing Schuerholz's ability both to handle turnover and rely upon homegrown talent as keys to sustaining the team's long run.

In all, it's an impressive legacy that deserves to be rewarded in Cooperstown. With the job of GM now in the limelight thanks to the wave of analytically-minded GMs who have followed in the wake of Moneyball, we're a long way from 2002, when Veterans Committee member Leonard Koppett lamented, "Players looked fondly upon Buzzie Bavasi after they had to deal with him. But someone like Schuerholz, who's gonna vote for him?" The guess here is that he'll get at least 75% of the voters and join Bud Selig in the Class of 2017.

George Steinbrenner

Often a bully and sometimes a buffoon, George Michael Steinbrenner III was unequivocally "The Boss," and occasionally as unhinged as the British monarch with whom he shared both a name and a numeral. A football player at Williams College and an assistant coach at Northwestern and Pudue, he fully subscribed to Vince Lombardi's "winning isn't everything, it's the only thing" ethos, often failing to understand that running a baseball team on a daily basis required a subtler touch and a deeper reserve of patience than his gridiron sensibility could muster.

Nonetheless, aside from Connie Mack and Walter O'Malley, no other owner in the history of baseball was as influential or successful over such a long period. Beyond O’Malley, who uprooted the Dodgers from Brooklyn, none gave more ammunition to his critics and detractors or unified so many in their hatred. Steinbrenner spent much of his tenure as a cartoon villain and was suspended from baseball by commissioners twice. Even in absentia, he had the foresight to embrace the dawn of free agency, and for all of his tyrannical meddling—hiring and firing 21 managers in his first 20 years and burning through general managers at a similarly absurd clip—he stayed out of the way of what his baseball men built in his absences long enough to preside over four pennant winners and two world champions from 1976 to '81 and six more pennants and four world champs from '96 to 2003, adding one final championship in '09, the year before his death.

For all of his notorious bluster, Steinbrenner was a big softy at heart, quick to put the Yankees name behind charitable causes and to give people in his organization second (and third, and fourth...) chances, just as he had received. In the end, he was the benevolent despot who restored the luster to the franchise, turning the Yankees into one of the most valuable properties in professional sports at the time of his death, worth an estimated $1.6 billion. Now run by son Hal, the team's estimated worth has climbed to $3.4 billion as of March 2016 (both figures according to Forbes).

A shipbuliding magnate from Cleveland, Steinbrenner led a group of investors that purchased the dilapidated franchise—which hadn't appeared in a World Series since 1964 or won since '62—from CBS in '73 for about $10 million. Initially, Steinbrenner pledged to keep his nose out of the team's business, saying, "We plan absentee ownership as far as running the Yankees is concerned.” But soon he was crowding out his fellow investors, starting with team president Mike Burke, who had run the team during the CBS era and negotiated with the city of New York to renovate Yankee Stadium. "Nothing is more limited than being a limited partner of George," minority owner John McMullen would later say.

Breaking down Today's Game Hall of Fame ballot, Part 2: Mark McGwire

Steinbrenner quickly ran afoul of the league, pleading guilty in August 1974 to charges of making illegal contributions to Richard Nixon's re-election campaign and of obstructing justice. Suspended by commissioner Bowie Kuhn for two years (later reduced to 15 months), he exerted his influence via the direction of Gabe Paul, who while still general manager of the Indians had initially paired Steinbrenner and Burke. Desperate to restore glory to the franchise, Steinbrenner embraced the opportunity to sign Athletics ace Catfish Hunter to a five-year, $3.35 million deal in December 1974, when A's owner Charlie O. Finley failed to make an annuity payment in a timely fashion. After being reinstated, he added superstar slugger Reggie Jackson in November 1976 via a five-year, $3 million deal after arbitrator Peter Seitz's landmark Messersmith-McNally decision kicked off the free agency era in earnest, then signed Goose Gossage a year later to a six-year, $2.75 million deal—despite the presence of reliever Sparky Lyle, who weeks earlier had won the AL Cy Young.

Under Martin, the Yankees won the pennant in 1976 but were swept in the World Series by the Reds. New York beat the Dodgers the following year, with Jackson—"Mr. October"—tying the series record with five homers, including three in the Game 6 clincher. Amid so much turmoil that the team became known as "The Bronx Zoo" (not coincidentally the title of Lyle's diary of that season), the Yankees repeated again in 1978, overcoming a 14-game mid-July deficit behind the Red Sox (whom they would beat in a Game 163 play-in) and a blowup between manager Billy Martin and Jackson. That fight led to the skipper's dismissal after he said of the superstar and the owner, "The two men deserve each other. One's a born liar, the other's convicted."

Fueled by more free-agent signings, particularly those of Tommy John and Dave Winfield, the Yankees won the 1981 AL pennant but lost a World Series rematch with the Dodgers, during which Steinbrenner injured his hand in what he claimed was a scuffle with two Dodgers fans in a hotel elevator. As the Dodgers clinched in the Bronx, he issued a gauche apology for his team's performance and a promise that plans to build a champion for 1982 would begin immediately. Those did not come to fruition, as his profligate spending and meddling led to the team's downfall. Prospects were swapped for over-the-hill veterans who flourished elsewhere, while the Yankees, despite posting the majors' best record from 1983 to '88, failed to win another AL East flag for more than a decade. After souring on Winfield (whom he nicknamed "Mr. May"), Steinbrenner tried to escape his 10-year contract by hiring a shady small-time gambler, Howard Spira, to dig up dirt. When commissioner Fay Vincent learned of the connection in 1990, he banned Steinbrenner for life—just over a year after President Ronald Reagan had pardoned his Nixon-era transgressions. The ban didn't last: Vincent reinstated Steinbrenner as of March 1, 1993, just before being ousted by the other owners.

Though as feared as ever, Steinbrenner stayed out of the way of what general manager Gene Michael—whom he'd hired and fired as manager in 1981 and '82—had done during his absence. Michael curbed the team's tendency to swap prospects, sowing the seeds of the forthcoming dynasty via astute drafting and amateur free-agent signings such as "the Core Four" of Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, Jorge Posada and Mariano Rivera, not to mention a brilliant deal that sent Roberto Kelly to Cincinnati for Paul O'Neill and freed up center field for Bernie Williams. Michael also hired manager Buck Showalter, whose four-season tenure through 1995 (when the Yankees made their first postseason appearance in 14 years) was the longest on Steinbrenner's watch thus far.

Breaking down Today's Game Hall of Fame ballot, Part 1: Baines, Belle, more

Michael was ousted along with Showalter after the Yankees' 1995 loss, with Steinbrenner hiring Bob Watson as GM. Watson's choice as manager was Joe Torre, a former National League MVP who in 14 seasons of managing the Mets, Braves and Cardinals had won just one division title and produced a .470 winning percentage. The tabloids derided the choice of "Clueless Joe," but the Yankees beat the Braves in the 1996 World Series, kicking off a 12-year run that included 10 division titles, six pennants and four World Championships, earning Torre a spot in Cooperstown in 2014.

Steinbrenner's persona as a benevolent despot emerged via his repeatedcaricaturing on Seinfeld, with series creator Larry David voicing the owner's long, petty diatribes. His soft, paternalistic side revealed itself via multiple second chances to Steve Howe, Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry, all of whom had battled substance abuse problems. While attaching the Yankees' name to charities, Steinbrenner bristled at the thought that they should include his competitors. "I would sooner send $1 million to save the whales than send it to the Pittsburgh Pirates," he told fellow owners.

With the Yankees restored to the top of the heap, Steinbrenner withstood the temptation to sell the team or move to the suburbs or Manhattan's West Side. Whatever the legerdemain it took to build the $1.5 billion "House That Ruthlessness Built" next door to "The House That Ruth Built," he ultimately understood that the Bronx was a key part of the Yankees' brand, as was the big-dollar spending that brought free agents Mike Mussina, Jason Giambi, Mark Teixeira and CC Sabathia and led to trades for Alex Rodriguez, Roger Clemens and Kevin Brown. Though he chafed at the credit that Torre and GM Brian Cashman—who took the reins in 1998 at age 30 after rising through the front office ranks—received and retained a semi-anonymous cabal of Tampa advisors who often undercut the Bronx brass, he finally ceded control of daily operations to sons Hal and Hank in late 2007, amid a chain of events that led to Torre's departure and Steinbrenner's receding from the public eye.

Ultimately, the indomitable owner's legacy is a complicated one. Neither a saint nor a pure font of evil, he understood that nothing drove financial success the way that winning did. He won more than any owner of his era and built the most valuable property in baseball. For all of his transgressions, you can't tell the story of the past four decades of baseball without him. I don't see how you can keep him out of Cooperstown, though I suspect that this panel of voters will.

Adapted from “Bluster and Luster: George Steinbrenner (1930–2010),” originally published a Baseball Prospectus in 2010.

Jay Jaffe is a contributing baseball writer for SI.com and the author of the upcoming book The Cooperstown Casebook on the Baseball Hall of Fame.