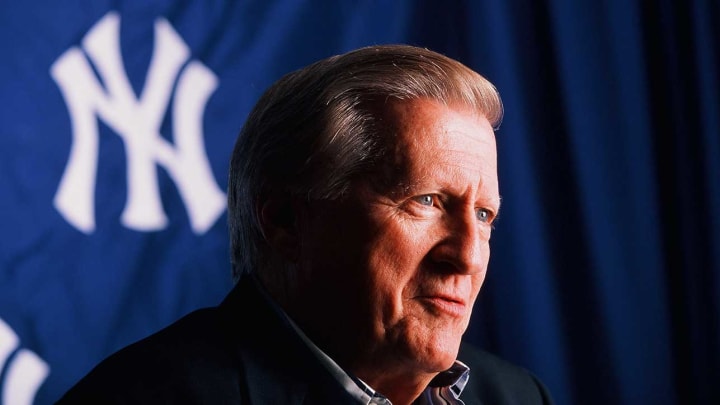

Why George Steinbrenner and Fellow Hall of Fame Nominees Probably Won't Reach Cooperstown

The official Baseball Writers Association of America ballot for the 2019 Hall of Fame election has yet to be released, but if you’re itching to fight about Cooperstown, here’s a modest battleground for you. On Monday, the Hall announced the candidates for this year’s Today’s Game Era ballot, comprised of 10 individuals: six players, three managers and one executive. But although there are some notable names present, including former all-time saves leader Lee Smith, irascible manager Lou Piniella, and deceased Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, the odds are against anyone in that group earning a bronze plaque.

For those unfamiliar with the era ballots, here’s a quick refresher. The Hall announced a revamp of its era-based voting blocs in 2016, which before 2010 had existed as the Veterans Committee (in variously named iterations). From ’10 through ’16, three separate 16-member groups voted on players, managers, front-office members and other baseball folks who had either fallen off the BBWAA ballot or never been up for consideration, grouped by eras: Expansion (1973 to the present), Golden (‘47–’72) and Pre-Integration (1876–1946). Each group comes up once every three years.

That format was changed two years ago to four 16-person committees: Early Baseball (1871–1949), Golden Days (1950–’69), Modern Baseball (‘70–’87) and Today’s Game (’88 to the present). Along with that came a new schedule geared toward evaluating candidates from the recent past more frequently than those of older times, which the original Veterans Committees had more or less exhausted. As such, this is the second time in three years that the Hall will vote upon the Today’s Game Era, which means that a number of these men have already been considered and rejected; like the BBWAA ballot, you need 75% or more of the vote to earn election. That robs this exercise of a good deal of its drama.

Forecasting the 2019-2023 Baseball Hall of Fame Inductees

(Before I dive into the names, a quick shoutout to former SI scribe Jay Jaffe, now over at FanGraphs, whose groundbreaking work on the Hall and invention of the JAWS stat—which uses Wins Above Replacement to rank a player relative to his enshrined peers—have been crucial to the modern evaluation of candidates.)

The full list of candidates is a who’s who of 1980s stardom. Harold Baines, Albert Belle, Joe Carter, Will Clark, Orel Hershiser and Smith comprise the players; Davey Johnson, Charlie Manuel and Piniella are the skippers; and Steinbrenner rounds out the group as the lone executive. Baines, Belle, Clark, Hershiser, Johnson, Piniella and Steinbrenner were all part of that aforementioned Today’s Game ballot two years ago, while Carter, Manuel and Smith make their debuts.

Between the BBWAA and the Veterans Committee, voters have rejected Baines, Belle, Clark and Hershiser multiple times, and with good reason. Baines is top-50 all-time in hits, total bases and RBIs, but that was because of a 21-year career in which he plodded along for a decade-plus as a creaky yet serviceable DH for five different teams, primarily the White Sox. He was a compiler and not much more. Belle had a ludicrous peak—from 1992 through ’98, he hit .303/.379/.593 with a 153 OPS+ and 285 home runs—but saw his career cut short by a hip injury, retiring after the 2000 season at just 33. His legendarily awful temper and personality didn’t help matters with Hall voters, as his stay on the ballot lasted just two years.

Clark was a wildly consistent hitter, with a .303/.384/.497 line across 15 seasons, but low career totals (only 284 home runs and 2,176 hits before he retired after the 2000 season at age 36) leave him below Hall standards. By the advanced numbers, he looks a little better: His career WAR is 56.5, better than enshrined first basemen Tony Perez and Orlando Cepeda, but still shy of the position average, to say nothing of the game’s elites.

Hershiser looked to be on a Hall of Fame track through 1989; in his first six full seasons, he made three All-Star teams, finished third in the NL Rookie of the Year voting in ’84, and was top five in the Cy Young results four times, including his lone win in ’88. But a torn rotator cuff suffered in 1990 wrecked him going forward, and while he pitched in the majors until the age of 41, he never again approached those late-80s heights. Like Clark, he’s well short on the WAR and JAWS fronts at his position.

As for the new names in Carter and Smith, the former has the most iconic moment of anyone on this list: his World Series-winning walk-off home run for the Blue Jays in 1993. But the five-time All-Star’s case isn’t much more than that. Carter’s free-swinging ways and awful defense took big chunks out of his WAR total; at just 19.2, he’s miles from the average in rightfield. Nor did that homer save him in his lone year on the ballot, in 2003, when he earned only 3.8% of the vote.

Smith, meanwhile, can point to his 13-year reign as the game’s saves king, from 1993 until 2006, when he lost the title to the recently inducted Trevor Hoffman. A seven-time All-Star, Smith led the league in saves four separate times and retired with 478 of them—third most all-time, behind Hoffman and Mariano Rivera (who will be on this year’s BBWAA ballot and is a lock for election). The valuation of relief pitchers for the Hall is tough to figure, but the writers weren’t able to come to consensus on Smith, who spent 15 years on the ballot but never got more than 50.6% of the vote (back in 2012) and finished at 34.2% in his last turn in ‘17. He likely has the best shot of any of the former players, though it’s a long one at best.

As for the managers, Johnson and Piniella garnered no significant support two years ago. The former is best known as the skipper of the world champion 1986 Mets, and his .562 winning percentage is the 10th best of any manager with 1,000 or more career victories. But his career on the bench was relatively short, and the ’86 Mets represent his only postseason success. Piniella also has a World Series title to his credit as a manager with the 1990 Reds, but like Johnson, his resume is full of playoff losers, most infamously the 116-win 2001 Mariners. He does rank 16th all-time in wins, but also 13th in losses thanks in large part to his years helming the expansion Devil Rays. Neither he nor Johnson measure up all that well to the managers already in Cooperstown.

The same holds true for Manuel. Beloved around the game, the West Virginia native has one major triumph to his name in the 2008 Phillies, but otherwise, he resembles Johnson and Piniella in being unable to capture more postseason glory despite several chances. And though he’s a member of the 1,000 Win Club, it’s only just barely: He finished his career 1,000–826. Manuel’s short time as a big league manager will almost certainly keep him out of the Hall.

Fast Facts About the 2018 Baseball Hall of Fame Class

That leaves Steinbrenner. No one on this ballot, save perhaps Belle, is a more controversial figure than the man synonymous with the Yankees, the team he owned from 1973 until his death in 2010. Brash and braying, he helped turn the team into a powerhouse in the 1970s through his early and eager embrace of free agency and oversaw the franchise’s dynasty years in the late 1990s. In between, though, he feuded with and fired managers constantly, interfered with the best-laid plans of his general managers, warred with his players through the press, and ruled over the Bombers like a tyrant. On top of that, he was suspended from the game twice, first in 1974 for 15 months over illegal campaign donations to Richard Nixon (which also earned him a felony conviction, later pardoned by Ronald Reagan), and again in 1990 for paying gambler Howard Spira to find dirt on disappointing free-agent signing Dave Winfield.

That latter ban was supposed to be for life but ended up lasting only three years. It was fortuitously timed, as well: With Steinbrenner sidelined, general manager Gene Michael was free to build the winning Yankees teams of the future, drafting and signing the prospects who would ultimately grow into a championship core. Over his final two decades in charge, Steinbrenner mostly though inconsistently stayed out of the way, letting Brian Cashman work while the team soared in value.

One of the most influential owners in the game’s history, Steinbrenner’s Hall of Fame case is nonetheless undercut somewhat by his suspensions. How willing the panel of voters is to overlook that will be the determining factor in his chances at getting a bronze plaque (he got fewer than five votes the last time he was up). If nothing else, it’d be amusing to see him honored the same weekend as Rivera, an all-time Yankees great who was nonetheless almost traded to the Mariners in 1996 until Steinbrenner was persuaded otherwise.

Ultimately, though, the bet here is that neither Steinbrenner nor anyone else will be joining Rivera and others in being inducted next July. The new Eras Committees have, in their first two years of existence, admitted four to the Hall’s ranks: Bud Selig and John Schuerholz in 2017, and Jack Morris and Alan Trammell last summer. This time around, expect to see a result more common with Veterans Committees of the past: a shutout.

Jon Tayler is a writer for SI.com. His most prized possession is a Rich Garces rookie card.