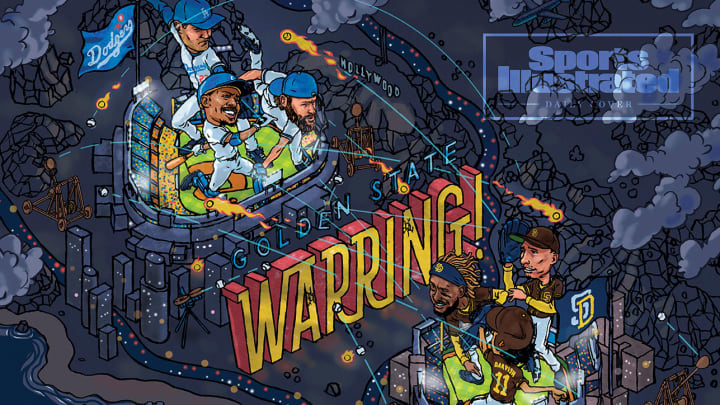

MLB's Next Great Rivalry Is Here

On Thanksgiving Day of 2002, Theo Epstein left Logan Airport in Boston for Nicaragua. The trip signaled one of the biggest economic growth periods in baseball history.

Epstein, the newly named Boston Red Sox GM, traveled there to sign free-agent pitcher José Contreras. Under new owner John Henry, Boston wanted not only to sign Contreras but also to announce they were taking dead aim at the New York Yankees. There was no real rivalry at the time. The Yankees dominated the Red Sox.

Epstein reserved all 12 rooms in the remote hotel where Contreras was staying just to box out the Yankees. Epstein stayed up late with Contreras, smoking Cuban cigars, drinking whiskey and all but wrapping up contract negotiations. The next day Epstein saw two men coming in and out of Contreras’s room. The Yankees not only found Contreras, they also signed him.

The Red Sox didn’t get Contreras, but they did change baseball. The trip began a commitment of taking on the Yankees—to spending money and building teams that could win more than 95 games. A real rivalry was born. It was the engine to the game’s crazy economic growth.

From 2003 to 2013, the Yankees and Red Sox won the most games, nine division titles, five pennants and four World Series titles. They played each other 217 times in those 11 seasons. The Red Sox won 109 of them. The Yankees won 108. Every one of them played out like a Shakespearean drama, only longer. During that time, MLB revenues jumped 83%, with the single biggest one-year spike this century, 11%, following Boston’s 2004 World Series championship.

The next great rivalry is here. It is Padres-Dodgers. San Diego, which hasn’t won a division title in 15 years, sent its intentions to Los Angeles by acquiring Yu Darvish, Blake Snell and Joe Musgrove. The Dodgers responded by signing a free-agent pitcher they didn’t need, Trevor Bauer, at the insane price of $85 million over two years. (Officially, Bauer has a $17 million third year at his choosing.) They signed Bauer because the Padres, second last year only to the Dodgers in run differential, had thrown down the gauntlet. Game on.

Asked if the team signed Bauer because of the challenge the Padres presented, one club source said, “Yes. You’re talking about probably the two best teams in baseball, and there is still a priority and a reward to finishing first in your division. Give ownership credit for signing off on this.”

When president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman presented the Bauer proposal to chief executive officer Mark Walter of Guggenheim Partners, Walter gave it the green light.

As in Boston in 2002, when Henry was in his first year of owning the Red Sox, an ownership change is raising the stakes of the rivalry. In November, Padres general partner Peter Seidler bought out the majority ownership from Ron Fowler. Fowler ran the club from a business standpoint. Seidler brings a more emotional perspective to the role.

Given the limitations of their market, the Padres are unlikely to compete with the Dodgers for a decade the way the Red Sox did with the Yankees. Boston is the country’s 10th biggest media market, as measured by Nielsen. San Diego ranks 27th. The Padres have nowhere near the national following of the Red Sox.

The better comparison in terms of staying power might be the Arizona Diamondbacks. They took on salaries and debt in 1999 during their second season. It paid off with three playoff teams in four years, including the franchise’s only World Series title. Two years later Arizona lost 111 games. The Diamondbacks have reached the postseason only three times in the 18 years since that four-year run.

The Padres never have won a World Series. Like the 2002 Red Sox, they know they are close to a franchise-changing title. The Dodgers were rightfully concerned San Diego had closed the gap on them. Enter the “need” for Bauer.

Bauer is an elite pitcher when it comes to durability and maxing out his ability. He manipulates the baseball as well as any active pitcher, constantly tweaking pitch shapes and sequences. He is Mike Mussina with more velocity.

Here is an example of Bauer’s weaponry. Over the past two seasons he has thrown 373 curveballs on two-strike counts. He has given up only 11 hits. Two-thirds of those curves are out of the strike zone, but hitters chase them them because of not only the sharp break but also how Bauer sets up the two-strike pitch.

What Bauer does not have is a long track record of elite performance. His career numbers at age 30 (75–64, 3.90, 195 starts, 3.85 FIP) are nearly identical to those of James Shields (72–63, 3.96, 184 starts, 3.91 FIP).

Bauer’s Cy Young Award season last year is notable because of his extreme increase in spin rates and his domination of poor teams. Unlike breaking pitches, four-seam spin rates generally are stable. They can fall due to injuries and rise again with health. They can rise with a gain in velocity. They also can rise with specially designed formulations of grip material.

Bauer’s four-seam fastball has remained fairly consistent in terms of velocity. Every year it has averaged between 92.9 and 94.6 mph. The spin on the pitch, however, took a hellacious jump last year. After ranging between 2,225 and 2,412 rpm for five years, it spiked to 2,776.

Until last year Bauer in his career reached 2,800 rpm with his four-seam fastball 42 times out of his 7,254 four-seam fastballs—less than six-tenths of 1%. Last year he did so almost every other pitch: 231 of 505.

Bauer made only three starts last year against winning teams. His career ERA against winning teams is 4.01, which ranks 29th among active pitchers with at least 75 such starts—below pitchers such as Alex Cobb (3.85), Mike Minor (3.74) and Mike Fiers (3.68).

The Dodgers did well to get the best pitcher on the market on a short-term deal. They are paying Bauer, Clayton Kershaw and David Price $87 million this season. Walker Buehler is their ace. Julio Urías, Dustin May and Tony Gonsolin are rising stars. Bottom line: The Dodgers are better with Bauer than without, despite his inappropriate behavior off the field.

The point also is that the Padres are pushing the Dodgers in the way Boston did New York, when the rivalry was the rising tide that rose all boats. Three months after New York signed Contreras, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner posed for the SI cover with Roger Clemens, Andy Pettitte, Jeff Weaver, Mussina and Contreras. David Wells opted out of the picture. The headline: “You Can’t Have Too Much Pitching.”

That fall the Yankees and Red Sox engaged in an epic American League Championship Series, one of the greatest postseason series ever staged. Through nine innings of the seventh game they were equals. A game that began with Clemens and Pedro Martinez ended in extra innings with an Aaron Boone home run. The Yankees lost to the Marlins in the World Series.

The Dodgers play San Diego 19 times this year, including in their last homestand. Maybe they will see them in the NLCS. In their run of eight straight division titles, the Dodgers are 97-49 (.664) against the Padres, including a three-game sweep in the playoffs last year. It has not been a real rivalry. Until now.

Darvish, Snell, Bauer, Buehler, Fernando Tatis Jr., Manny Machado, Eric Hosmer, Mookie Betts, Cody Bellinger and Max Muncy are all controlled by the Padres or Dodgers for the next three seasons. A window just opened, and even if it is a fraction of what Yankees-Red Sox wrought, the rivalry will be good for baseball, not just Southern California.

Tom Verducci is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who has covered Major League Baseball since 1981. He also serves as an analyst for FOX Sports and the MLB Network; is a New York Times best-selling author; and cohosts The Book of Joe podcast with Joe Maddon. A five-time Emmy Award winner across three categories (studio analyst, reporter, short form writing) and nominated in a fourth (game analyst), he is a three-time National Sportswriter of the Year winner, two-time National Magazine Award finalist, and a Penn State Distinguished Alumnus Award recipient. Verducci is a member of the National Sports Media Hall of Fame, Baseball Writers Association of America (including past New York chapter chairman) and a Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1993. He also is the only writer to be a game analyst for World Series telecasts. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, with whom he has two children.