Revealing Tom Verducci’s 2023 Baseball Hall of Fame Ballot

Don’t let this election fool you. The flow of players into the Hall of Fame is accelerating.

Here are the number of players annually elected by the baseball writers to the Hall of Fame in my first six years voting 30 years ago: 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1. Voting was so tough that 324-game winner Don Sutton waited five years to get in.

Here are the number of players elected in the same manner in the past six years: 4, 4, 2, 0, 1, 1.

Five electees in six years gave way to 12 in six years. What changed? The volume of information about a player and how fast that information travels. And that has created a willingness to vote for more players, a trend that feeds upon itself, as I can personally attest.

Just look at the incredible trajectory of Scott Rolen. The third baseman received only 10% support in his first year on the ballot (with the caveat that PED candidates made for a crowded ballot). Since then, he has climbed to 17%, 35%, 53%, 63% and this year to 76.3%, becoming only the ninth third baseman elected by the writers. No one has ever made a bigger climb on the ballot. Rolen’s 10% opening is the lowest first-year support for someone eventually elected by the writers, displacing Duke Snider, who needed 11 years to overcome his 17% start.

In keeping with the spirit of a bigger Hall, my ballot includes a switch from “no” to “yes” for one player. But some standards are more immutable, which is how I explain not voting for Carlos Beltrán.

Here is my ballot, explained:

The New Guy

Todd Helton

I did not vote for Helton his first four years on the ballot. His home/road splits bothered me. People point to his road numbers as being impressive, but his road OPS (.855) is worse than that of Jack Clark (.858) and less than the overall OPS of John Olerud (.863), Mark Teixeira (.869) and Will Clark (.890), good players but none of whom has been close to being a Hall of Famer. Helton hit 62% of his home runs at home. He finished in the top five in MVP voting just once. After age 30, he never hit 30 homers or drove in 100 runs.

So what changed? For one, that flow into the Hall has been accelerating. Guys like Edgar Martínez, Larry Walker and Harold Baines (through a special committee) became Hall of Famers.

More than that, I questioned whether I was slicing the numbers too thinly when it came to Helton’s advantage hitting with Coors Field as his home ballpark. After all, adjusted OPS does the work of factoring in park and league. And when I trusted OPS+ to do the measuring, it favored Helton.

Helton posted a career OPS+ of 133. He is one of 45 Hall-eligible players with an OPS+ that high over at least 9,000 plate appearances. Shorthand: He hit really well for a very long time. Let’s throw out four of those 45 hitters who are tainted by PED connections. The other 41 are all in the Hall of Fame with one exception: Helton.

Helton is the only player with an OPS+ of 133 not tied to PEDs who is not in the Hall of Fame (min. 9,000 plate appearances). That measurement, which takes in park effect, alone convinced me.

For further consideration, there is this non-park-adjusted gem: Helton hit .316 with 2,519 hits and 369 home runs. Only six other hitters reached those three thresholds: Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Ted Williams, Lou Gehrig, Stan Musial and Vladimir Guerrero, all first-ballot Hall of Famers.

The Holdovers

Jeff Kent

This is the writers’ worst blunder since Fred McGriff. Kent finished his 10th year on the ballot without getting even 46.5%. Like McGriff, who sailed in unanimously by the Contemporary Baseball Committee, Kent will be voted in the first time he gets a chance with the committee, in December 2025.

Why the lack of support? Writers put way too much faith in notoriously unreliable defensive metrics. Kent played more than 2,000 games at second base—88% of his career—and usually with very good teams. Only 10 players started more games at second base than Kent. Good teams do not keep handing jobs to really bad defenders; they move them or find somebody else.

Teams kept Kent at second base, because he was a true outlier: a second baseman who hit like a first baseman. Kent had more home runs, more 100-RBI seasons and more starts batting cleanup than any second baseman in history. That’s a Hall of Famer.

He also was better in run-producing clutch spots than overall. This is the stuff of Cooperstown: Kent is the only middle infielder in the expansion era to hit .300 and slug .500 with runners in scoring position (min.: 2,000 plate appearances).

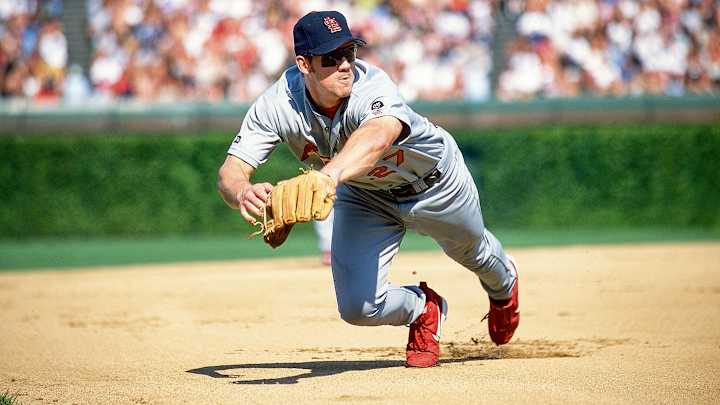

Scott Rolen

The biggest knock on Rolen has to do with volume. Beset by injuries, Rolen is the first infielder with less than 9,000 PA elected by the writers among all players who debuted after 1947.

And yet he is one of only five third basemen with 300 homers and 100 steals (Mike Schmidt, Adrián Beltré, Chipper Jones and George Brett are the others). He posted eight qualified seasons with an OPS+ of 125—only Schmidt (12), Eddie Mathews (11), George Brett (10) and Wade Boggs (9) had more elite seasons among third basemen.

So, yes, he played long enough. It is his defense (8 Gold Gloves) and baserunning (32% runs scored; only Pie Traynor and Paul Molitor were better among BBWAA-elected third basemen) that put him over the top.

Billy Wagner

He did not reach 1,000 innings and his postseason résumé is short and poor. But Wagner, a one-inning closer, was a Hall of Famer because he dominated hitters like no one else.

Among all pitchers who threw 900 innings, Wagner ranks first in strikeout percentage, batting average against, WHIP and hits per nine innings. Yes, you could argue starters such as David Cone, Bret Saberhagen or Dave Stieb might have been dominant one-inning closers with that reduced role, but you judge a player on what he was asked to do, not what might have been.

The Omission

Carlos Beltrán

I don’t know how I will feel next year. But I could not stomach voting for Beltrán in his first year of eligibility because of his key role—a leadership role—in the 2017 Astros sign-stealing scandal.

Beltrán has Hall of Fame numbers. They are nearly identical to those of Andre Dawson. Beltrán, Dawson, Willie Mays, Barry Bonds and Alex Rodriguez are the only players with 2,500 hits, 400 home runs and 300 stolen bases.

Upon joining Houston in 2017 after three years with the Yankees, Beltrán told the Astros they were “behind the times” in stealing signs. Beltrán was a key figure in setting up a live video feed positioned close to the dugout to steal signs. According to The Athletic, his influence was so great teammates called him “The Godfather.”

When first confronted about his role when the scandal broke in 2019, Beltrán lied, saying he was not aware of a center field camera and that the team deciphered signs only in a legal manner. The Mets took away his newly minted managerial gig.

He did not give his first detailed interview until 2022, when he continued to dodge the truth, telling the YES Network, “A lot of people always ask me why you didn’t stop it. And my answer is, I didn’t stop it the same way no one stopped it. This is working for us. Why you gonna stop something that is working for you? So, if the organization would’ve said something to us, we would have stopped it for sure.”

But teammate Brian McCann did ask him to stop midway through the season and manager A.J. Hinch smashed the television monitor to signal his opposition to the scheme. And still Beltrán persisted. According to The Athletic, a source said Beltrán “disregarded it and steamrolled everybody.”

I’ve always used the oft-misconstrued “character clause” as a measure of sportsmanship, not citizenship. Did you play the game fairly? In this case, the answer is no.

Stealing signs is not at the same as level as using PEDS—a banned, federally controlled substance since 1990 that comes with known health risks. The growth of in-game technology happened recently and quickly; it took the Astros’ scandal for MLB to get its arms around it. But Beltrán’s leading and persistent behavior in that cheating scheme cannot be easily dismissed, especially on a first ballot.

Tom Verducci is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who has covered Major League Baseball since 1981. He also serves as an analyst for FOX Sports and the MLB Network; is a New York Times best-selling author; and cohosts The Book of Joe podcast with Joe Maddon. A five-time Emmy Award winner across three categories (studio analyst, reporter, short form writing) and nominated in a fourth (game analyst), he is a three-time National Sportswriter of the Year winner, two-time National Magazine Award finalist, and a Penn State Distinguished Alumnus Award recipient. Verducci is a member of the National Sports Media Hall of Fame, Baseball Writers Association of America (including past New York chapter chairman) and a Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1993. He also is the only writer to be a game analyst for World Series telecasts. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, with whom he has two children.