Nick Newell, a congenital amputee MMA fighter, goes for title on historic NBC broadcast

New York Yankees pitcher Jim Abbott emerged from the dugout to see what all the commotion was about. At the spectators’ fence, a young mother stood with her seven-year-old son talking to the security guards. Abbott saw the child was like him, a congenital amputee born without a portion of an appendage. The boy was missing his left hand and forearm just below the elbow joint.

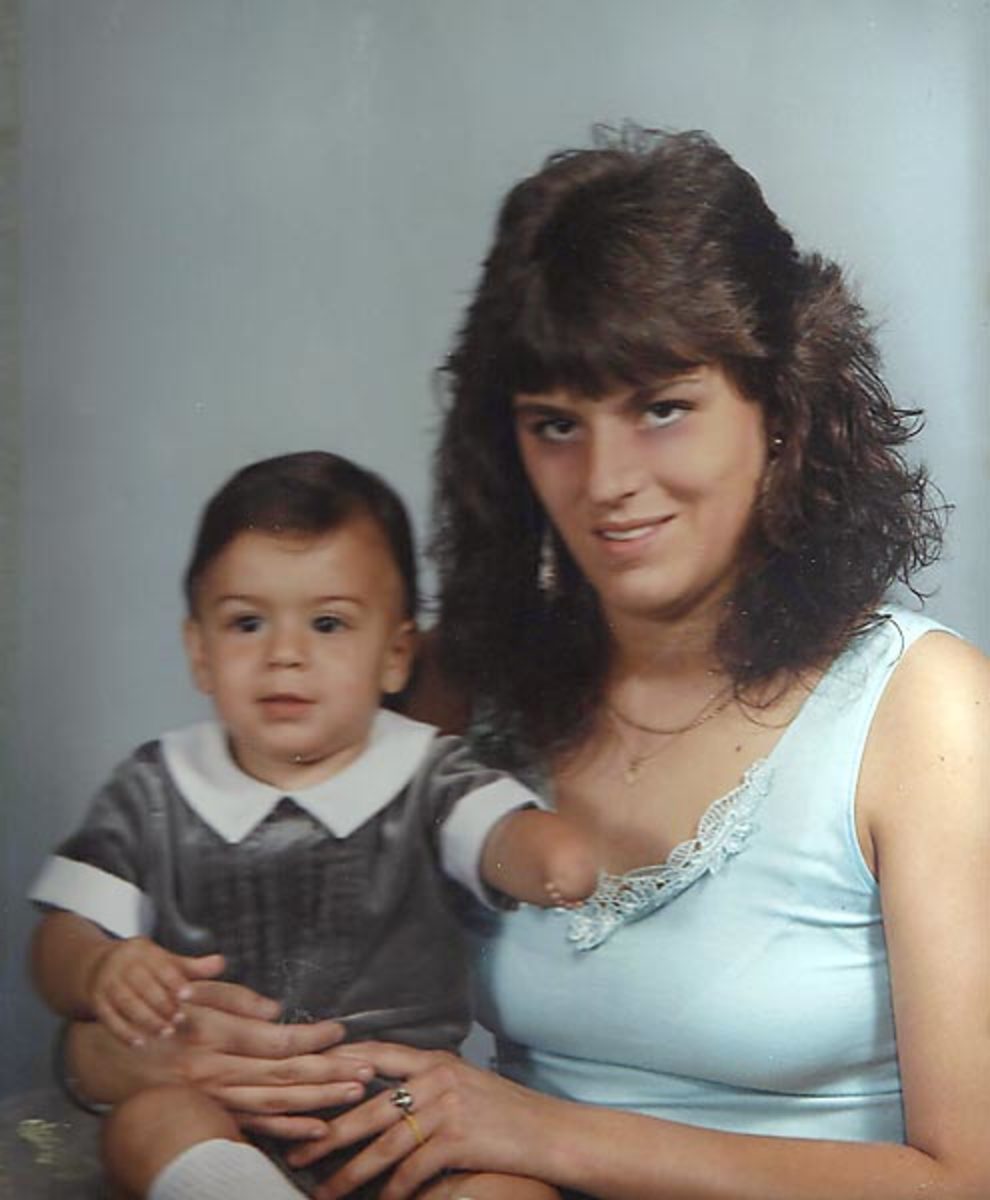

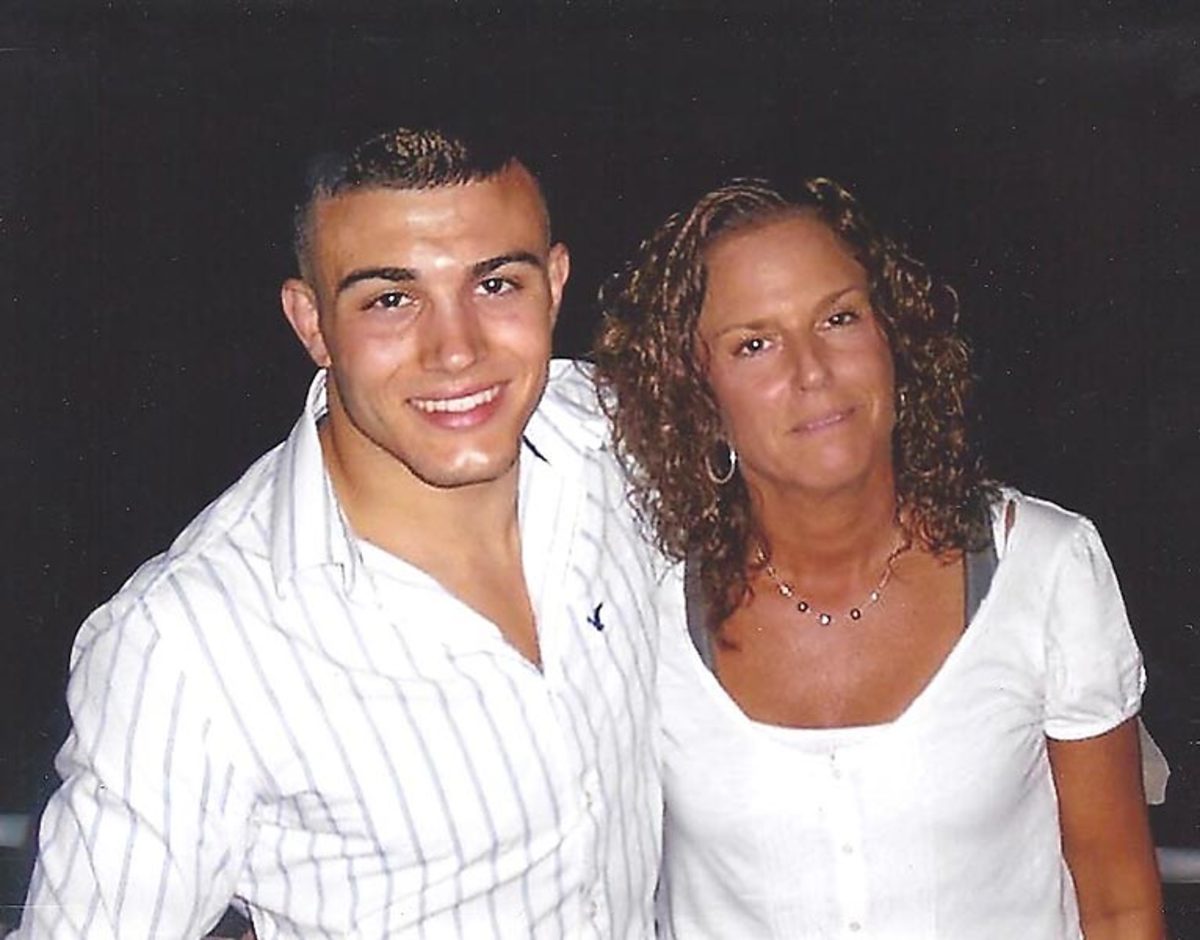

Stacey Newell remembers that day well.

“We got to the fence and I asked, ‘Do you think Jim Abbott’s coming out?’ and security kind of looked at me like, ‘Lady, if I had a dime for every time somebody showed up with a one-handed kid,’” said Newell, a single mother from Milford, Conn., who was determined to have her son meet his idol.

Though Abbott wasn’t pitching that day, he ushered Stacey to hand her son, Nick, over the fence to him. He then took the star-struck youngster into the dugout for a tour and signed a ball for him before handing him back to his mom.

Against the odds, that young boy would grow up to become someone in sports. On Saturday, Newell challenges World Series of Fighting lightweight champion Justin Gaethje live on NBC (4 p.m. ET/1 p.m. PT). The bout is significant for a couple of reasons. It will be the first time a congenital amputee will fight for an MMA title in a nationally televised promotion. It will also be the very first time that NBC, a broadcast network hesitant to get into the niche sport in the past, will air a live MMA event. Previous WSOF events have aired only on NBC Sports Network, an offshoot cable channel, and there is a solid argument that NBC’s turnaround has a lot to do with Newell, the WSOF’s most popular fighter.

“When we signed with the WSOF, we were told there’d be the possibility that the promotion would get a network deal,” said Newell’s manager, Angelo Bodetti. “I think Nick may have tipped the scales.”

Rare Photos of Nick Newell

The undefeated Newell (11-0) is the clear underdog in the championship bout, not necessarily based on his physical limitations, but for the fact that Gaethje, also 11-0, is an agile, explosive athlete who has faced a tougher pool of opponents. But as cliché as it sounds, Newell has thrived as an underdog all his life, due in no small part to his unflappable attitude.

“I don’t put too much weight into what people think or say about me. Whether they doubt my abilities or not, I don’t really care,” said the 28-year-old Newell. “I can’t promise that I’ll win all the time, but what I can promise is that I’ll go out there and do everything I can to win. I’m putting it all on green and hoping it hits.”

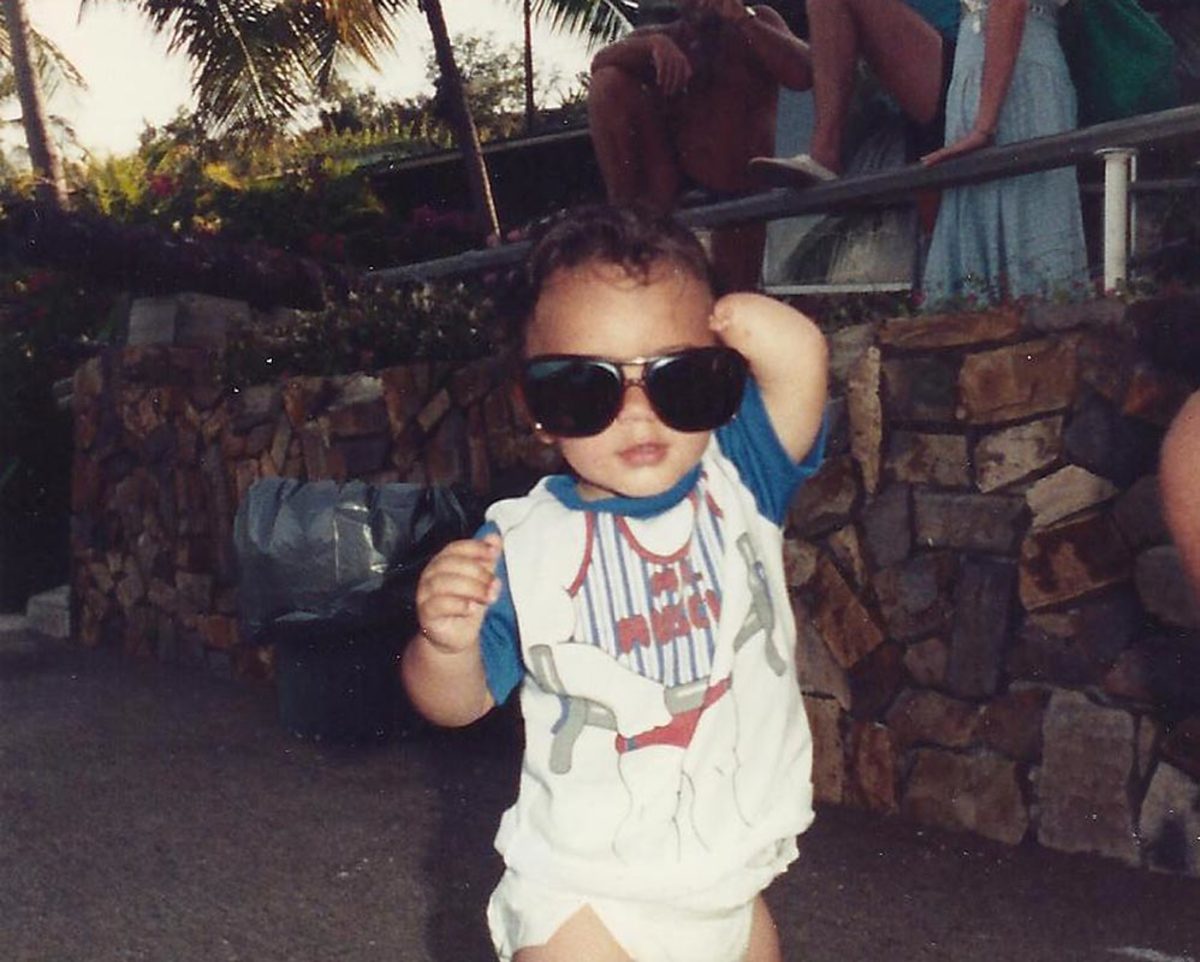

Newell’s give-it-all approach can be tracked back to his earliest years. He was a persistent baby, who learned to crawl on schedule, though he waddled along off-balance, propping himself up on his left elbow.

His mother, Stacey, found the medical world’s practices for children with limb differences perplexing, if not frustrating. In her naiveté, she was talked into providing the “right body image” for her son with a prosthetic arm, though she wondered why a six-month-old baby might care about that.

“It looked like a little Barbie doll arm; it matched the skin color and you strapped it on,” she said. “What do you think a six-month-old would do with it? He took it off. He threw it. He put it in his mouth. I’d find it all over the place.”

Stacey attached Velcro to the prosthetic and Nick’s toys to try to make it functional for him, but when the doctors showed Stacey a high-school-age amputee with a myoelectric prosthesis (commonly referred to as a “bionic arm,”) she insisted Nick not have to wait for it.

“If they could make a big one, they could make a little one. I didn’t have the money, but I pressed the issue and made a big deal about it,” said Stacey. “He was the first [younger] kid to walk out the door with one.”

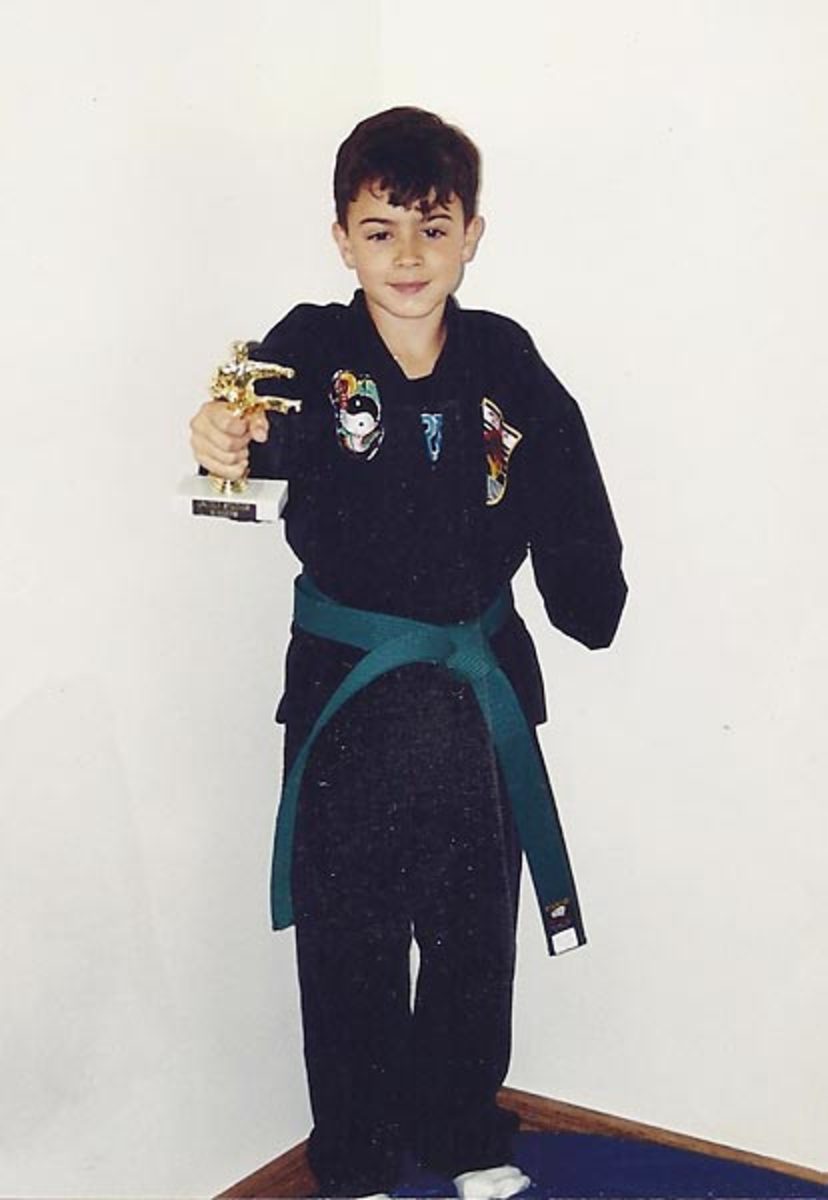

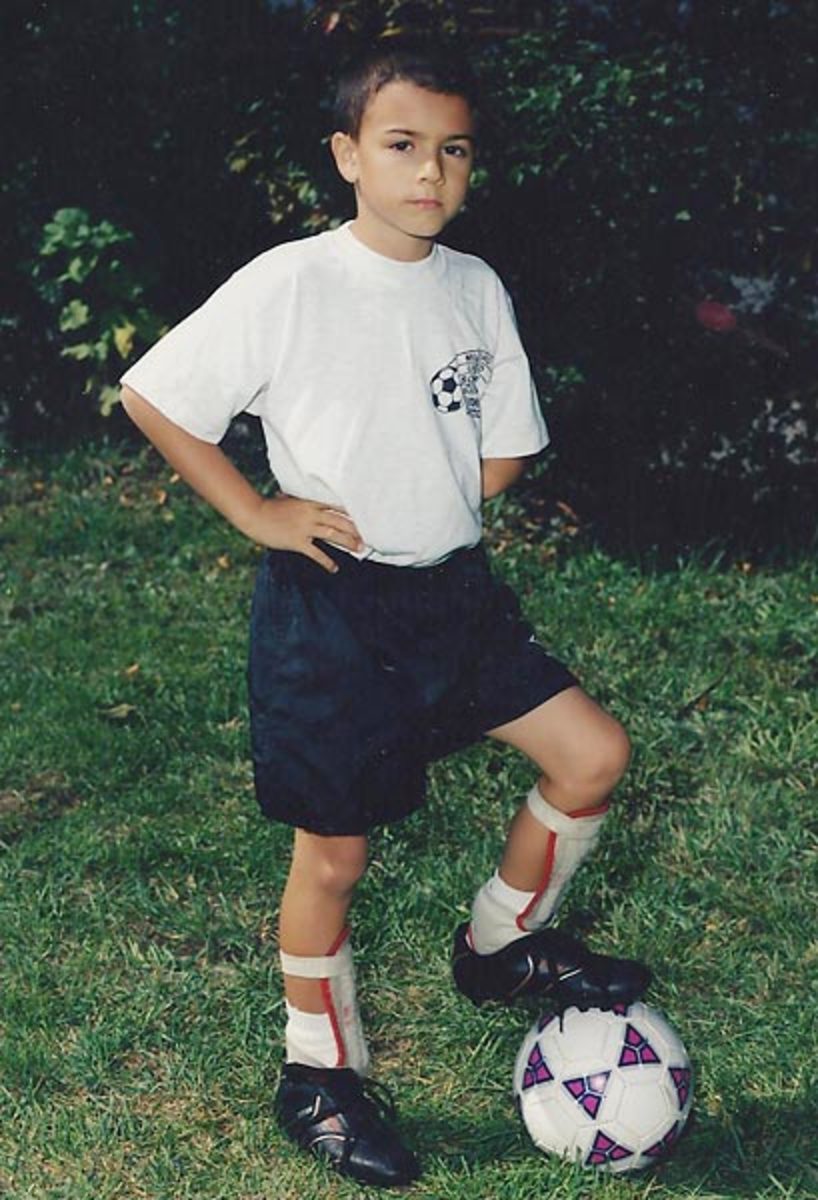

Naturally athletic, Newell was drawn to sports as a toddler; his mother enrolled him in his first Karate class at age three. Soccer, baseball and basketball followed.

“The biggest issue was that I felt I had to give him a good shot [at life]. Any sport he wanted to do, I signed him up,” said Stacey. “That’s what you do for your children. If you want to do something, you’re going to do it.”

By first grade, Nick’s bionic arm became more of a heavy hindrance as he raced out onto the soccer field to play with the other kids.

“I told myself that this was ridiculous. If anything, I was telling him that he wasn’t OK by making him wear this arm that did nothing for him. It was, more or less, to make everyone else aesthetically OK with it,” said Stacey. “I told him to take it off. He could run so much faster without it, but it had to be his choice.” Nick shed the apparatus and never looked back.

Nick’s father was an absentee parent, said Stacey, who married a longtime friend from high school three years ago. When she needed help to better her son’s life, she didn’t let her pride get in the way.

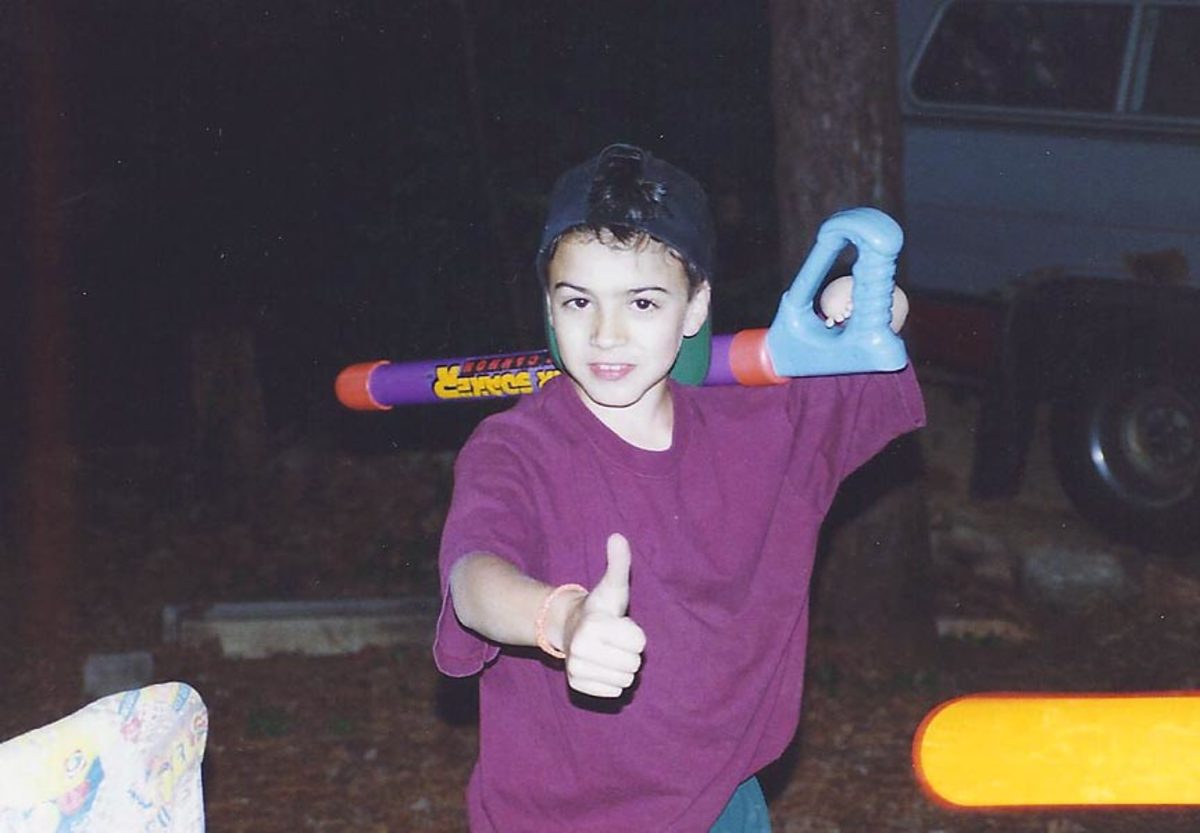

“Nick wanted to play baseball around age seven or eight, but hadn’t played T-ball or gone through the regular ranks that kids go through up to that age,” said Stacey. “I bought him the glove and bat, and a coach would take him to batting practice on this own. The coach knew it was just Nick and I and that I’d do anything for him, but who wants to go out in the front yard and play catch with a mom who can’t really throw a ball?”

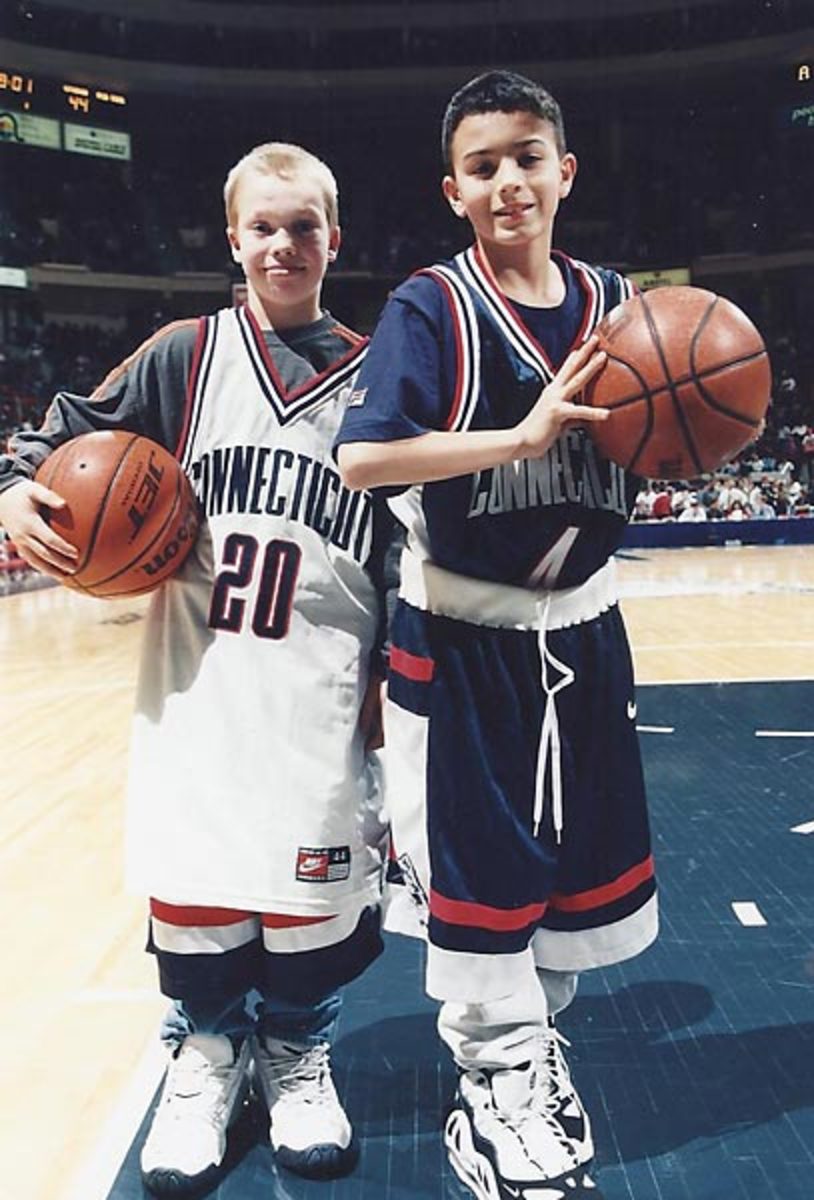

Nick, in turn, learned to surround himself with positive people when out of his mother’s watchful eye. He still has the same core group of friends that he made in kindergarten, and had a knack for tuning out the bullies who tried to alienate him.

“In gym class, I wasn’t picked last,” said Nick. “If anything, I was always picked earlier because I gave it my all.”

The future fighter had other strong male influences along the way. One was his high-school wrestling coach Matt Schoonmaker, who worked with Nick for four years.

UFC 175 Crash Course: Weidman vs. Machida

As the story goes, Nick had a tough go at his first wrestling practice, went home and cried his eyes out. He didn’t want to go back the next day; it was just too difficult to keep up with the other wrestlers. Had Nick not had Stacey as his mother, he might have done just that. “She wouldn’t let me quit,” said Nick. “She told me I’d made a commitment and I was going to honor that.”

Coach Schoonmaker said Nick’s missing hand and forearm wasn’t really a concern from the start; they would just find a way to adapt in practice.

“He was little. We needed a 103-pounder, so we were happy we were going to have somebody fill the weight, to be honest,” said Schoonmaker. “By the time he was a sophomore, I knew he was going to be good.”

Nick’s record was 8-22 his freshman year, with six of the wins coming by forfeit because the opposing team didn’t have anyone wrestling in his weight category. No one ever turned Nick down as an opponent due to his limb difference.

At one of the earlier practices that first year, Stacey remembers visiting the wrestling room to see how her son was faring. The sessions always started with a warm-up that included push-ups, but Nick couldn’t do them with one hand. Over that next summer, Stacey scraped enough money together to send Nick to a wrestling camp and buy him a gym membership. The next fall, Nick was pumping out as many push-ups –- one-handed, of course -- as his teammates.

Riding into his senior year, Nick hairline-fractured the bone in his left elbow during a league match -- an injury that could have ended his entire season. After conferring with Nick’s physician, his mother and coach opted not to tell Nick how severe the injury really was.

“Instead, we told him it was a deep contusion and we’d have to ice it occasionally,” said Schoonmaker. “They said there wasn’t a threat of it getting worse and as long as he could stand the pain, go ahead.”

Once the doctor gave the OK, it was an easy decision for Stacey to go along with the ruse.

“I knew how badly he’d wanted it and I didn’t want him to be afraid,” she said. “I felt if we’d told him, he would have lost his confidence.”

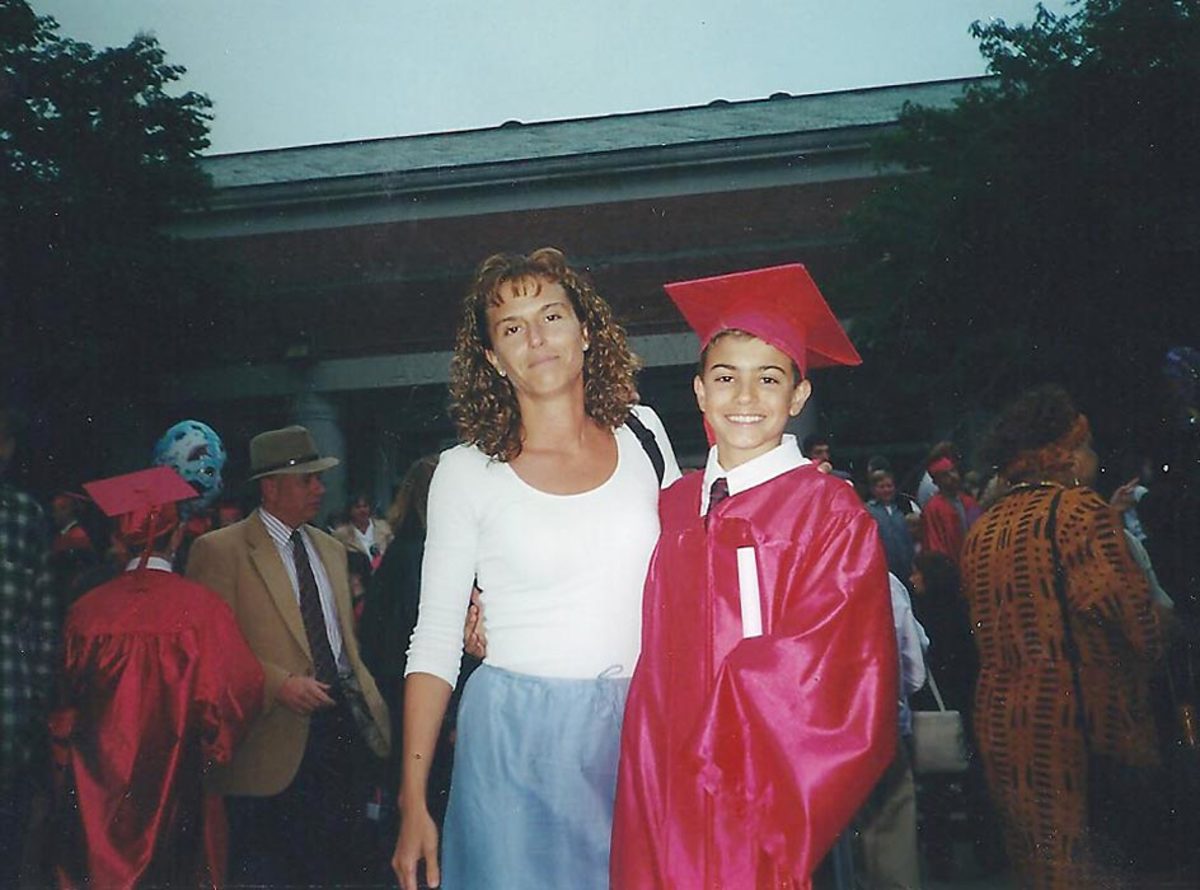

Newell’s season went on as planned and he had a robust senior year, earning a 53-10 record at 130 pounds. He was named an All-State wrestler and placed fourth at the New England Championship in 2004, said Schoonmaker. Nick made the newspaper many times.

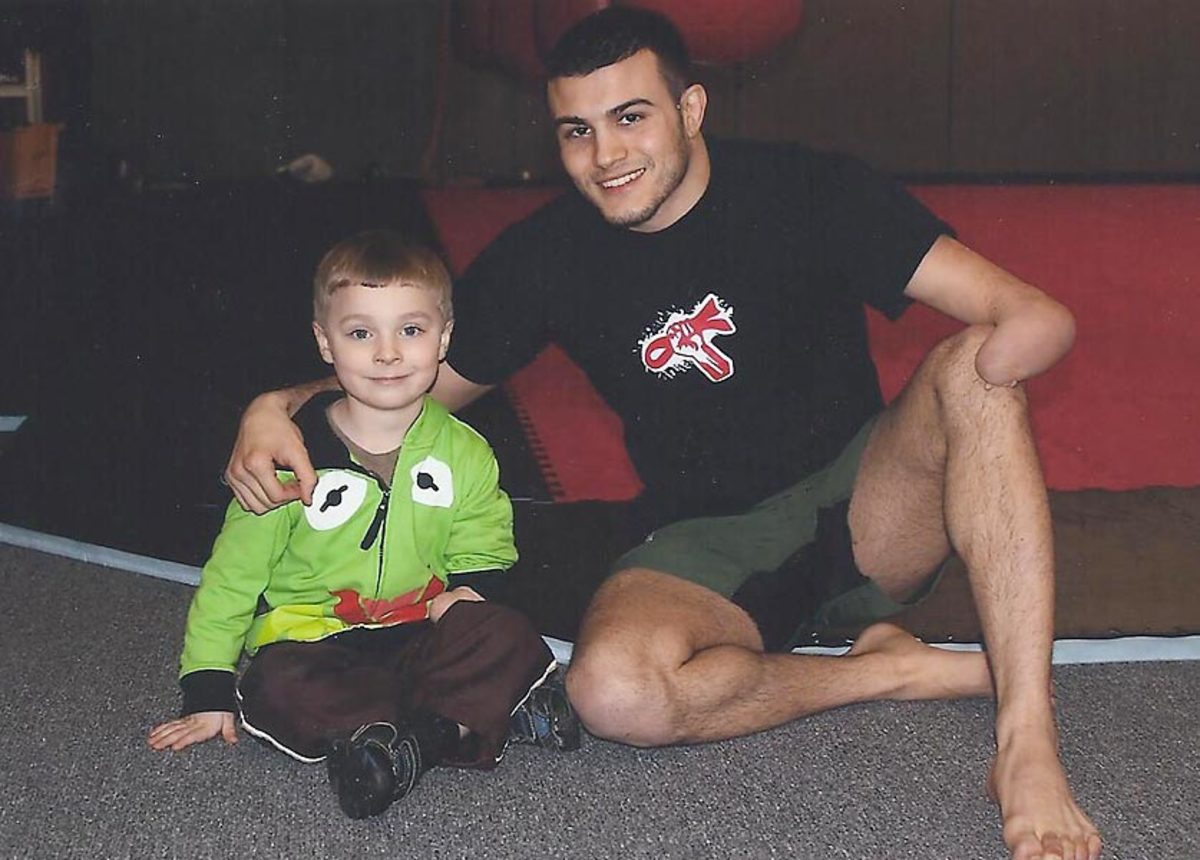

He was recruited to wrestle at Western New England College (Division III), and was captain of the team his junior and senior years. During that final year, Newell and his roommate caught an episode of The Ultimate Fighter, and the college graduate walked through the door of the Fighting Arts Academy in 2008. Today, Newell lives with his coach, Jeremy Libeszewski, his wife, Jesse, and their three children to stay close to the Springfield, Mass., gym. He still visits his mom most weekends and she still does his laundry for him.

The perceived advantages and disadvantages Nick might have in MMA are still up for debate. Pat Miletich, a well-respected former fighter, coach and on-air analyst, remarked during one Newell-fight telecast that he has a stark advantage since opponents can’t prepare for his modified chokes and holds.

Newell’s MMA coach, Libeszewski, doesn’t agree.

“Every fighter has advantages and disadvantages,” said Libeszewski. “If you’re tall, you get to be tall. If you’re explosive, you’re explosive. If you’re flexible, you’re flexible. Every fighter introduces a new problem, so I really don’t buy into that too much. Sometimes people try to make it seem like [Nick’s holds] are much more difficult than they really are. They’re not that much different [from tradition] than people think they are.”

There are moves, like the Kimura shoulder lock, that Newell avoids without the benefit of a two-handed grip. On his feet, the unorthodox Newell must work his angles at all times to avoid the right high kick, for which he doesn’t have a left forearm and hand to defend against.

“If he stayed in the pocket and brawled, that would be a disadvantage, but he’s more of an intelligent striker,” said Libeszewski. “He uses his angles where if you wanted to kick to that side of his body, you’d have to have a very long reach and change your own angle. He stays ahead with his angles.”

Newell never attempts to hit with the end of his left arm. “If I hit someone with the end of my left arm, I’d probably break it,” said Nick, who dislocated his elbow in practices early on while attempting to do it.

Instead, Newell is a big proponent of elbows. His right one juts out more than normal and his left is imperative without the benefit of a second fist.

“With only one limb, he has to close the gap [between him and his opponent] more,” said Libeszewski. “He can’t throw a traditional one-two, so he hits with his left elbow. Jab, elbow is his one-two.”

In his last two fights for the WSOF, Newell has caught his opponents with a modified guillotine choke. Fans might not understand the mechanics of what he’s doing, but they see an unlikely underdog winning and respond to that. Physically speaking, Newell shouldn’t have attempted to become a fighter, so to come as far as he has inspires many, both within and outside the limb-difference community.

Last August, after Newell’s first win in the WSOF, retired Yankees pitcher and fellow congenital amputee Jim Abbott contacted Nick on Twitter. Abbott invited Newell out to lunch in Los Angeles and the two discussed their mutual experiences in their respective sports.

What impressed Abbott most about Newell was his willingness to open himself and his experiences up to others.

“A lot of the kids I’ve met are shy and I would have been too, [but] Nick’s kind of a charismatic kid,” said Abbott. “He’s confident and into encouraging people. It’s not his goal; he’s out there making his mark in the fight world, but I think he’s embraced that there are other people along for the ride and I’m proud of him for that.”