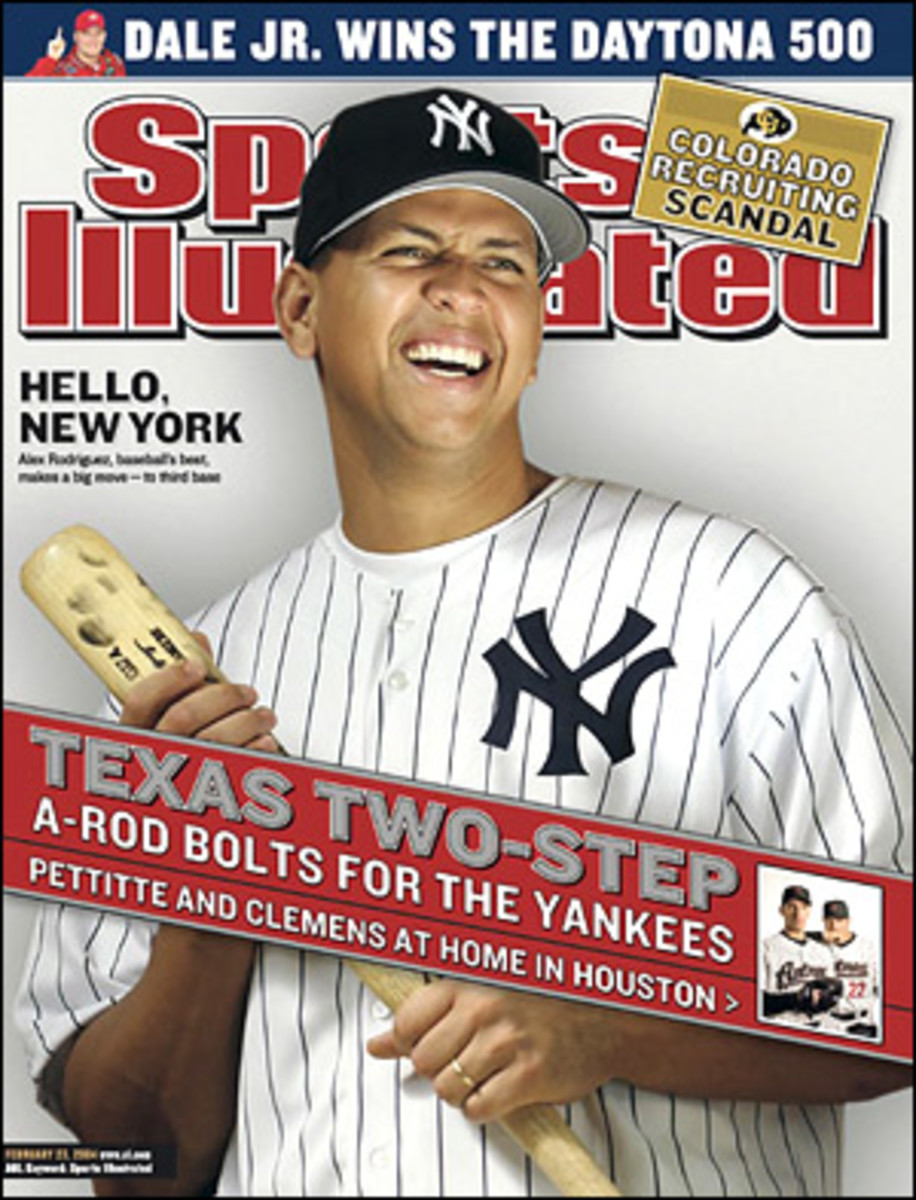

SI Flashback: Hello, New York

Issue date: February 23, 2004

Once upon a time, Mrs. O'Leary left a lantern too close to her cow, five burglars broke into a Watergate office, and Aaron Boone decided to play a little pickup basketball. History, Voltaire observed, is little else than a picture of human crimes and misfortunes. Over the coming years the exact details are to be revealed as to how the misfortune of Boone, the New York Yankees third baseman who blew out his left knee in a Jan. 16 hoops dalliance, will alter baseball history, especially the raging neo-Peloponnesian War between the Yankees and the Boston Red Sox. But altered it shall be.

When Boone went down, the Yankees needed a third baseman, and when the Yankees needed a third baseman, Texas Rangers shortstop Alex Rodriguez reconsidered his objection to playing third base. And when Rodriguez reconsidered, the Yankees succeeded in less than 72 hours where the Red Sox had failed for five constipated weeks earlier this winter, swinging an unprecedented trade over the weekend for a reigning MVP who also is the game's best all-around player.

Boone, mind you, is the same chap who four months ago hit the 11th-inning home run that ended Game 7 of the American League Championship Series and Boston's season. Now this A-Rod business. In the annals of New England oral history he will forever be referred to as Aaron Bleeping Boone. "I only wish to God," one Red Sox official bemoaned after the trade, "that Aaron Boone never picked up a basketball."

With Rodriguez, the Yankees become the Beatles of baseball, such is their talent and global star power. They open camp this week with 17 All-Stars, including seven regulars who have won an MVP award or finished among the top seven in the voting, and four of the eight players in baseball history who signed a contract worth more than $100 million (Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, Jason Giambi and Kevin Brown). The teams chasing this club can only hope that the mass of New York's stars is so great that it collapses inward like a black hole.

How, for instance, will Rodriguez, 28, and Jeter, 29, coexist? Both are signed through 2009 with no-trade clauses; the superior defender of the two, Rodriguez, will play out of position; and their friendship has been strained since A-Rod's critical comments about Jeter in an '01 magazine interview. "Everybody knows their best lineup would be A-Rod at short and Jeter at second," one American League manager says, "but it won't happen because it's Jeter's team."

As of Sunday night Rodriguez had not spoken to Jeter about the trade, but as for deferring to the Yankees shortstop and moving to third base, A-Rod says, "I don't see it as a big deal at all. I look at it as a new challenge. I won two Gold Gloves and an MVP at shortstop. I thought I achieved just about everything personally at shortstop. Now it's time to win. I've always thought of myself as a team player. Playing third base is the ultimate team move."

Never before have George Steinbrenner's Yankees been more befitting of Fitzgerald's take on the very rich: "They are different from you and me." With the Rodriguez trade the other 29 franchises look on New York with further contempt not only because it makes the Yankees richer, but also because they were lucky. A-Rod fell into their lap less than a week before spring training started, and they were able to negotiate such a relatively small financial obligation to Rodriguez ($16 million annual average) that they will pay him less than Jeter and Giambi, less than what the Red Sox will pay Manny Ramirez and Pedro Martinez, and less than what the Houston Astros pay 35-year-old first baseman Jeff Bagwell.

What's more, Rodriguez will add only $2.4 million to New York's 2004 payroll as it stood before Boone played basketball. While the Yankees will pay Rodriguez $15 million this year, they got off the hook for the combined $12.6 million they would have owed Boone ($5 million, assuming he gets only termination pay for violating his contract's no-basketball clause); failed third base prospect Drew Henson ($2.2 million), who quit to pursue an NFL career; and second baseman Alfonso Soriano ($5.4 million), who was sent to Texas with a minor leaguer to be named in the Rodriguez deal. The Rangers are to choose from a list of five prospects before March 31.

Texas agreed to pay $67 million of the $179 million (over seven years) left on Rodriguez's original record-busting $252 million, 10-year contract. The trade still lightened the Rangers' long-term obligations by about $120 million (including interest), freeing them to save or spend the savings as they rebuild what has been a last-place team for four years running. For instance, Texas immediately worked to finalize a five-year extension for third baseman Hank Blalock, a commitment that one team source said would not have been possible without the A-Rod deal.

The Rangers' $67 million sweetener did, however, give some pause to commissioner Bud Selig, who, according to one major league source, heard complaints from owners such as the Baltimore Orioles' Peter Angelos. Selig had pushed hard to accommodate Rodriguez's trade to Boston so the game's best player could get to a competitive, high-visibility franchise. He fretted more about Rodriguez as a Yankee, one source in the commissioner's office said, because New York's payroll of about $190 million figures to be about $70 million ahead of the rest of the field, led by Boston. Selig, though, approved the trade on Monday after almost three days of study.

Boston could have had Rodriguez in December for Ramirez, but after trying to restructure A-Rod's contract, it killed the deal because of a $15 million difference between what it was willing to pay Rodriguez and what the union would allow in the devaluation of A-Rod's contract. When the Red Sox heard late last week that New York was engaged in talks with Texas about Rodriguez, they made a futile attempt to get back in the hunt, according to two sources involved in the negotiations. "Too little, too late," one source said.

With the trade Texas owner Tom Hicks made the figurative admission that his business plan to build a winning team around Rodriguez was a colossal failure. A-Rod missed only one game over three years in Texas while hitting .305 with 156 home runs and 395 RBIs, but other investments, such as $65 million over five years for pitcher Chan Ho Park, bombed, and Hicks could not afford to continue pumping money into the payroll. Talk about a costly divorce: By 2025, when the last of his deferred payments is due, Hicks will have paid Rodriguez $140 million for three years of service.

After the Boston talks died, Hicks had given Rodriguez a let's-make-up bouquet: On Jan. 25 he named A-Rod captain and promised a long-term relationship. It lasted three weeks. On Feb. 8 Scott Boras, Rodriguez's agent, called Yankees general manager Brian Cashman about another client, free-agent first baseman Travis Lee. Cashman mentioned how much trouble he was having trying to replace Boone. He had failed to get Adrian Beltre from the Los Angeles Dodgers, for instance. Then it hit Boras: Why not Rodriguez? A Mets fan growing up, Rodriguez had always wanted to play in New York. Boras made a joke about it to Cashman to plant the seed of an idea, then immediately called Rodriguez.

"You'd have to decide what the [shortstop] position means to you," Boras told him, "and understand what you'd be giving up for a chance to win. Think about it."

Rodriguez called Boras back the next day and said, "Let's do it."

Said Boras on Sunday, "I knew for the last three years how hard it's been on Alex to be on a losing team and to have to hear that it's because of his contract. I also knew the business plan the Rangers were talking was not what was presented to him three years ago. The situation was possibly going to get worse."

On Feb. 10 the Rangers conducted an internal conference call with Rodriguez, Boras, Hicks, G.M. John Hart and manager Buck Showalter regarding the direction of the club. Boras just happened to mention that Rodriguez might reconsider a trade to the Yankees. Hicks scoffed at the idea. "Alex isn't going to play third base," the owner said. "He's always said that."

"Alex," Boras said, "what do you think about third base?"

"I wouldn't rule it out," Rodriguez said.

Silence fell over the line. Said Boras on Sunday, "Frankly, Tom Hicks was stunned."

The next day Hart and Cashman were negotiating the framework of the deal. By Sunday, Rodriguez had his Yankees uniform number picked out: 13, his high school football number. His usual baseball number, 3, was retired by the Yankees in homage to another young slugger who slipped through Boston's fingers to New York: Babe Ruth.

"Once Scott brought it to my attention, it made perfect sense," Rodriguez says about moving to third base to be a Yankee. "I began to think about the pinstripes. I felt the allure of the tradition and the opportunity to win and asked myself, Why not do it?

"You know the best part? Getting there while I'm still young and knowing I have seven years to play with Derek and set my legacy as far as being a part of Yankees history. Getting there at 37 and playing two years wouldn't be the same."

His Yankees history, born of misfortune, already has begun.

Issue date: February 23, 2004