SI Flashback: Rocket Science

Roger Clemens's last memory of his stepfather, the man he calls "my father," is of the spinning red lights and wail of the siren as the ambulance pulled away. Nine-year-old Roger watched through a basement window while standing on a table he'd hauled atop an old couch. His older sisters, Brenda and Janet, had rushed him to the basement just after their stepfather, Woody Booher, had dropped to the floor of their Vandalia, Texas, home with a heart attack. Roger would never see him alive again.

Thirty years later only a few other memories of Woody remain, like assorted snapshots in an old shoe box. The gallon of Blue Bell ice cream he would bring home every other day after his shift at the tool-and-die company. The sultry evenings when Roger and Woody would curl up together on the floor to watch Bonanza and, during commercial breaks, the way Woody would tickle Roger's face with his five o'clock stubble. The rides Woody gave Roger to Roger's ball games--always an hour early, never trusting Bess and the girls to be done fixin' their hair and such soon enough to get his son there on time. The horse Roger would tie to a tree in the front yard, knowing Woody insisted that the family's five steeds be kept out back, and the subsequent cleanup job that would be imposed on him.

There's not much more. Two fathers by nine--his mother left his biological father, Bill, when Roger was 3 1/2 months old--and then suddenly none. Nine years are nothing. Maybe they're crueler than nothing. They're long enough for a few isolated images to form in the darkroom of the mind. Dots that can't be con-nected. "Ever since I got to the big leagues, I've noticed fathers of players waiting outside the clubhouse for their sons," says Clemens, the New York Yan-kees' ace righthander. "I remember Mo Vaughn's dad in Boston. Andy Pettitte's dad has been around here. I always thought how special that would be."

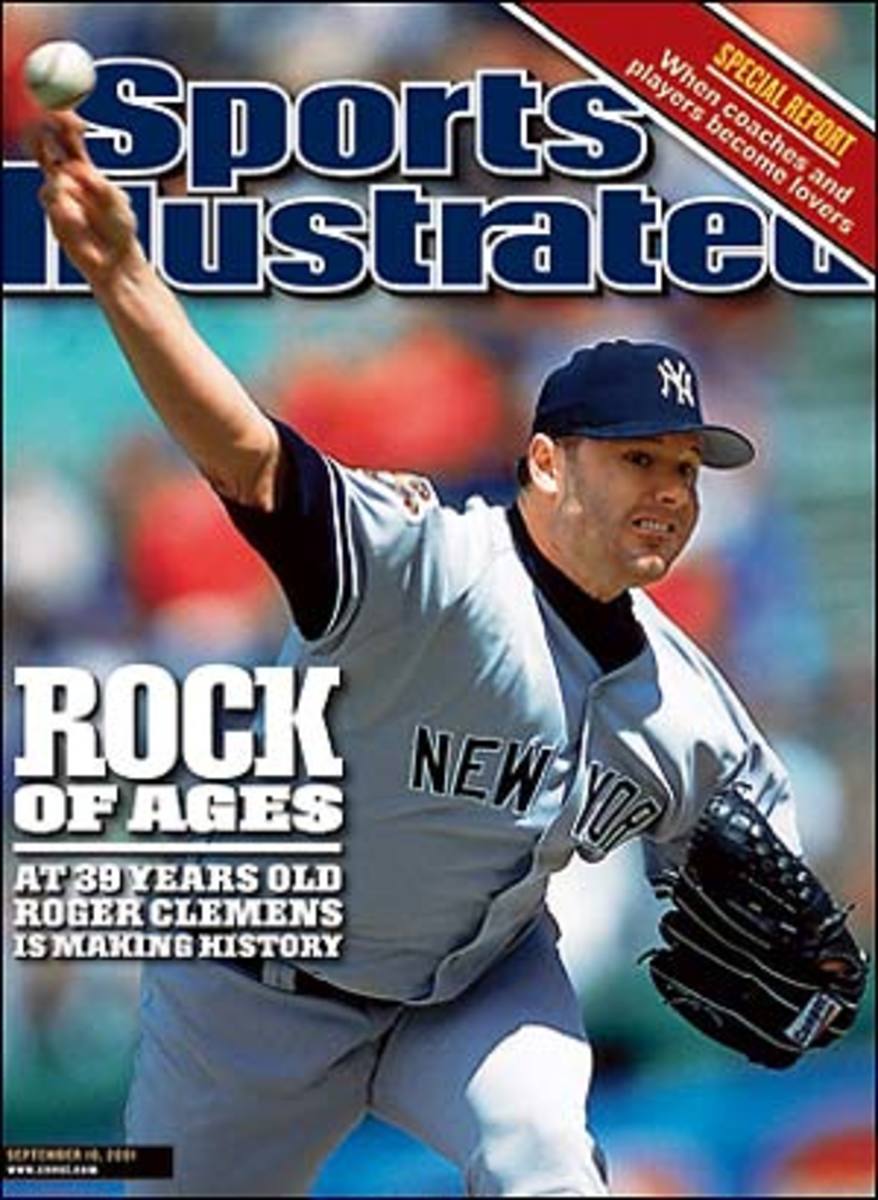

Today Woody Booher's son is as close to an unbeatable pitcher as there has ever been in baseball. With career victory 278 last Friday, a 3-1 conquest of the Boston Red Sox in which he scattered seven hits while striking out 10 in seven innings, Clemens became the first man in the 101-year history of the American League to start a season 18-1. (National Leaguers Rube Marquard, Don Newcombe and Elroy Face did so in 1912, '55 and '59, respectively; Face finished the '59 season with that mark and a .947 winning percentage--the major league record.) Through Sunday his 186 strikeouts led the American League, and his 3.48 ERA ranked sixth. Clemens's victory set the tone for New York's suffocating three-game sweep, which was capped by righty Mike Mussina's 1-0 Sunday win, in which a two-strike single by the Red Sox' Carl Everett broke up a perfect game with two outs in the ninth.

Clemens turned 39 years old on Aug. 4 and is the father of four sons, the oldest of whom just started high school. Fathers of teenagers aren't supposed to be blowing 96-mph heaters past Gen X batters and taking Wite-Out to the record book. They're supposed to be standing on the sideline at their kid's first high school football practice. Clemens, by his will and his wealth (he's in the first season of a two-year, $ 30.9 million deal with New York), can do both. One day last month he was home in Katy, Texas (about 30 miles from Houston), thanks to the time-share jet he owns with golfer Justin Leonard and two businessmen, watching his 14-year-old son, Koby, a defensive end, go through his first drills with the Memorial High squad. Two days later Roger was mowing down the Tampa Bay Devil Rays at Yankee Stadium for win number 16.

"The best investment I ever made," Clemens calls the jet, his share of which he bought last year, his second with New York. He uses the aircraft to fly home the night before every Yankees off day, no matter where the club is playing. Roger's family uses it to visit him. His sons have served as batboys for some New York road games, and they and his wife, Debbie, occasionally join him in the Big Apple. If Debbie and the kids aren't with him, Roger calls home at least three times a day, so often that when Debbie saw the Yankee Stadium switchboard number pop up on her caller ID during Roger's aforementioned win over Tampa Bay, she picked up the phone and cooed, "Oh, honey, are you thinking about us?" It turned out to be a front office employee checking to see if she needed help getting the satellite television feed of the game.

"Last year he invited the team to his house for a barbecue," says New York manager Joe Torre, "and while there I got a sense of how he's been able to keep going. With most guys his age or even younger, they get, I don't want to say pressure, but influence from home, with [wives and children] asking a lot, 'When is Daddy coming home?' But he's made his family a big part of his career."

Says Clemens, "I have a great team here with the Yankees. And it's like I have another great team at home. There's no way I could be doing what I'm doing without both of them."

True, the three-time defending world champs are a pitcher's dream. New York travels with two strength coaches, a massage therapist, two trainers, a sports psychologist and the richest collection of ballplayers ever assembled, including the game's best closer, Mariano Rivera. Through Sunday the Yankees had averaged 6.39 runs for Clemens, fifth most among American League starters. Six times this year Clemens had left a game trailing, but only once, on May 20 against the Seattle Mariners, had his teammates failed to get him off the hook. Clemens had left with a lead 19 times (he had no complete games), and only once had his bullpen not locked down his W. The bottom line: The Yankees were 25-3 when they gave him the ball (and 56-53 when they gave it to anyone else).

Says Fran Pirazolla, a sports psychologist who works with the Yankees, "Men-tally, Roger is one of the strongest athletes I've ever been around. When children lose a parent, they can go in two directions. Roger has made it a source of strength. He's always looking after the people around the team, trainers, batboys, whomever, asking if he can do anything for them. He has this sense of responsibility that's fatherly in a way, even among his teammates."

Clemens has introduced Pettitte, a fellow Texan, to his famously grueling conditioning program. (Lefthander Pettitte, who relied on 89-mph sinkers and cutters, now can fire 94-mph four-seam fastballs past hitters.) Clemens also let rookie lefties Randy Keisler and Ted Lilly join him during a workout in Baltimore in July. Lilly grew dizzy and nearly passed out, and Keisler vomited. "Or maybe it was the other way around," Clemens says, laughing.

Throughout almost 18 major league seasons (the first 13 with the Red Sox and the next two with the Toronto Blue Jays), Clemens has been a fitness fanatic. He so refined his training sessions with Blue Jays strength coach Brian McNamee that Toronto catcher Darrin Fletcher nicknamed them "Navy SEAL workouts." Clemens won his fourth and record fifth Cy Young Awards with the Blue Jays and then was traded to New York following the 1998 season for lefthander David Wells, lefty setup man Graeme Lloyd and second baseman Homer Bush. After Clemens slipped to 14-10 with the Yankees in 1999, New York hired McNamee as its assistant strength coach. From July 2, 2000 (when Clemens returned to action after straining his right groin muscle), through Sunday, he'd gone 27-3 over 46 starts.

Between outings Clemens religiously adheres to McNamee's tightly choreographed program of distance running, agility drills, weight training, 600 daily abdominal crunches and assorted other tortures. "One time he wanted me to ride a stationary bike, and I told him I never thought it gave you much of a workout," Clemens says. "He told me, 'Give me 17 minutes.' After 17 minutes I thought my legs would explode."

Clemens takes great pride in having stopped his baseball biological clock. He will tell you that he still runs three miles in 19 to 20 1/2 minutes, that he still weighs 232 pounds, that he still wears slacks with a 36-inch waist (though they must be tailored to allow for his massive thighs) and that he can still reach for a mid-90s fastball at will--the same specs he had at least 10 years ago. "He's a freak of nature, the kind of pitcher who comes along once in a generation, maybe every 25 to 30 years," says Devil Rays pitching coach Bill Fischer, Clemens's pitching coach from 1985 to '91 in Boston. "He's like Tom Seaver or Nolan Ryan. At 39 the s.o.b. is as good as when I had him. To go 18-1, I don't care if you're pitching for God's All-America team, that's mighty hard to do. He can pitch as long as he wants."

There's another benefit to the maniacal training besides staying fit. Clemens says all that sweat equity gives him a high comfort level when he takes the mound. How prepared is he? Through Sunday he had not permitted a first-inning earned run in 21 of his 28 starts. "I know I've done everything I could to be ready for that fifth day," he says. "Sometimes you hear a guy when he retires talk about regrets. You won't hear that from me. I know I haven't left anything in the bag. I enjoy the work. I enjoy being the guy people count on to carry the mail. I admit there are times when my body might feel sluggish, but then I'll go out to the mound and hear a kid yell my nickname, and that will pump me up."

Clemens is keenly aware of baseball history and his place in it. (Referring to Pettitte, for instance, he says, "I told him he can chase down Whitey Ford's Yankees records, if he wants.") He reads books on the sport's greats, such as one on Walter Johnson given to him by a descendant of the Big Train, and taps into the Internet to brush up on legends he's passing in the record book. Rube Marquard? "I'll have to look him up," Clemens says. For the record, Marquard was 25 when he started an unequaled 19-1 for the 1912 Giants. He retired at 38.

How long can Clemens last? He so tightly knits his family and career that he answers the question with we, as in, "We thought for a long time we were going to call it quits in 2000." Instead, he signed an extension last August that in-cludes an option year in 2003. He likes the fact that Koby and second son Kory, 13, are old enough now to understand the dedication it takes to be a professional athlete, and that Kacy, 7, and Kody, 5, have fun running around the clubhouse. "We signed a contract with the Yankees, so we intend to honor that," he says, "but I can't predict anything. I don't know how my body will feel next year or the year after that."

Says Debbie, "He's at a very comfortable point in his life. I know getting 300 wins is important to him. But after 300, what else is there?"

There are always more names to learn about in the record book. There are more abdominal crunches to do, more sub-seven-minute miles to run, more days to keep a 36-inch waist and a 96-mph fastball in his armament against age. There are, too, more flights home for Woody Booher's son to make it all work. That's Rocket science, the kind even a teenager understands.

One day last year Roger turned to Koby and said, "Son, the day I win my 300th game, I'm going to leave my glove on the mound and come on home."

Koby laughed. "Who are you kidding?" he said. "The day you win your 300th, you'll be thinking about 305."