Lessons from ProElite's death

Two years ago, as it unveiled itself at the posh Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, Calif., the group behind ProElite Inc. -- Doug DeLuca (a film and television producer) and Gary Shaw (a boxing promoter) -- heralded the company as a legitimate contender to the Ultimate Fighting Championship, buoyed by a broadcast deal and partnership with Showtime Networks.

"You may not believe in us today," said the bombastic Shaw. "But if you're smart, you will."

Somewhere out there, despite mounting evidence the business of mixed martial arts is tougher than a $3 steak, other wannabe promoters with deep pockets and a thirst to challenge the UFC will convince themselves they've got what it takes. With its newly minted EliteXC brand, ProElite fit that mold in December 2006. On the heels of the botched World Fighting Alliance, which signed several top fighters including Quinton Jackson and Ryoto Machida before flopping and selling its assets to the UFC, ProElite passed itself off as different.

It may have taken 17 events, but a quick postmortem reveals the people and philosophies behind ProElite and EliteXC were destined to fall short. Future promoters -- smart ones, at least -- may want to look at EliteXC, the International Fight League, Bodog Fight and the WFA for clues on what not to do.

Here, now, are the six most glaring things that led to the collapse of EliteXC.

1. Going public

Don't walk into MMA if you're going to rely upon public financing. It's simply too difficult to appaear viable as a company with your books open for scrutiny. The nature of the business lends itself to those who can adapt on the fly. Being public would seem to lessen that necessary flexibility.

Years after entrenching power as the top promoter in the sport, UFC executives shared stories of being $40 million in the hole and on the verge of giving up. What would have happened had quarterly filings revealed one ugly bottom line after another? It's entirely possible the business could not have survived. But as a private entity, the UFC was shielded from that kind of speculation. Like the IFL, ProElite was not.

2. Lack of commitment

Don't call yourself an elite MMA promoter if it's not the first thing you think about in the morning and the last thing you think about before going to bed.

There's no denying the passion that UFC President Dana White has brought to his company. When Lorenzo Fertitta decided he needed to spend more time focusing on the UFC, he stepped down from his position as a billion dollar casino mogul to do so. That drive was missing from ProElite, which did not feature a crew of MMA-first guys at the top. Shaw had his boxing business to fall back upon. DeLuca his various entertainment ventures, of which ProElite was clearly a part.

3. Using MMA as a sideshow

Others inside the company lived the sport, but they were on the fight side. The same could not be said, especially early on, of executives driving the ProElite ship.

4. The three O's: overspending, overreaching and over reacting

EliteXC was the major focus of ProElite's live-event strategy, but it wasn't the only thing the company hoped to accomplish. Pouring millions of dollars (nearly $20 million, according to one source), ProElite concentrated heavily on developing its web site, which it hoped would become a hub for MMA fans as a social networking site. But proelite.com, led by the overpaid and over-hyped Kelly Perdew, made famous by the reality show The Apprentice, never generated anything more than indifference. Also, ProElite lived beyond its means, renting a lavish office in West Los Angeles that housed a massive -- some say unnecessarily large -- staff.

When moves were first made to cut costs, ProElite looked to the dot-com side. Layoffs came in January 2008, and more followed as Charles F. Champion replaced DeLuca as CEO. But sources suggest that Champion, more a numbers guy than an MMA person, was focused more on preparing ProElite for sale to Showtime, and the damage from the previous administration was too much to recover from.

Remember that hideous dragon from the first EliteXC event in February 2007? It cost a couple hundred thousand dollars and has remained in some Mississippi storage facility ever since. That kind of over the top spending was emblematic of the early attitude that spending -- on anything -- was fine. That mindset led to the purchase or licensing of several established regional brands, which never came close to delivering a return on the investment.

5. Too many chiefs

Don't make decisions by committee. A successful fight promotion must have a vision executed from the top down. ProElite, at least when it came to the fight team, was a mess. Following EliteXC's event in Honolulu in September 2007, the fight team was assembled at the company's L.A. offices.

Gary Shaw, Jared Shaw, J.T. Steele, Rich Chou, J.D. Penn, JeremyLappen and T.J. Thompson met in person while Terry Trebilcock joined them over the phone. Each man clearly wanted to be heard and felt like he had something to say. It was at that meeting that Thompson said he was told Jared Shaw, Steele and Chou were tabbed, to the frustration of others at the meeting, as the group's matchmaking trio. But beyond that, and particularly in the vacuum created after Gary Shaw's ouster in July of this year, there wasn't a consistent voice in the group.

6. The Kimbo fiasco, now dubbed "Standgate"

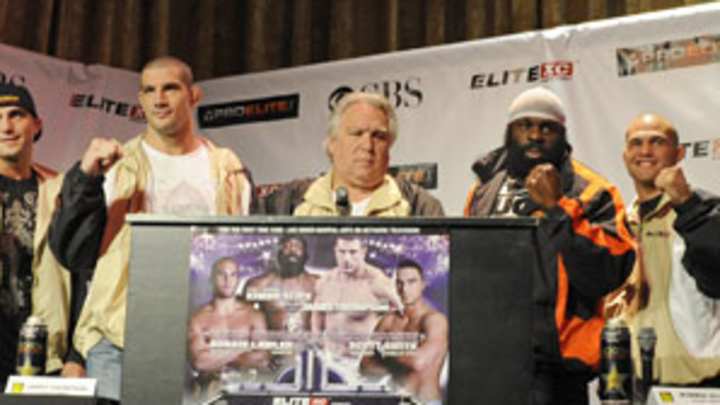

Don't mess with the product. From its inception, EliteXC seemed intent on delivering a stand-up friendly product. At the group's first press conference at the Roosevelt, Gary Shaw came under fire for comments he made about a 15-second ground rule, which would have limited action on the floor had it been implemented.

The matchmaking, too, was geared towards striking-heavy affairs. All that came crashing down following allegations EliteXC officials manipulated a fight on CBS between Kevin "Kimbo Slice" Ferguson and Seth Petruzelli to guarantee it would not hit the floor.

Company executives have repeatedly denied any wrongdoing. However, following Monday's news that ProElite was going under, Thompson, a consultant brought on after his Icon Sport fight promotion was acquired by ProElite, went on the record to say he believes executives inside EliteXC paid Petruzelli to stand with Slice.

A storm of negative press followed, as did a 13-day investigation from the Florida State Boxing Commission. On Thursday, the Florida Department of Business and Regulation announced their inquiries failed to uncover anything improper. Thompson was not summoned to speak. Sources in the company say the controversy is a major reason Showtime and CBS did not step up with 11th-hour funding that could have saved a company $55 million in debt.

The bottom line is ProElite -- maliciously or not -- attempted to manipulate MMA. The IFL did the same when it changed its round structure and rules. MMA fans want MMA, not a bastardized form of the sport. And that's a lesson for everyone.