Red Sox react to Manny's misstep

When Jason Bay first found out Thursday that Manny Ramirez, the man whom he had replaced in left field at Fenway Park, had been suspended for failing a drug test, his first reaction was "I'm going to get a lot of questions about him and I don't even know him."

Dustin Pedroia actually broke the news to his friend and Dodgers outfielder Andre Ethier with a noontime phone call. By the time Pedroia made it to the ballpark a few hours later, the reality had set in that this would be every bit an issue for him to deal with as it was for his buddy 3,000 miles away. "It's going to be one of those days, isn't it?" he said to a Red Sox PR staffer.

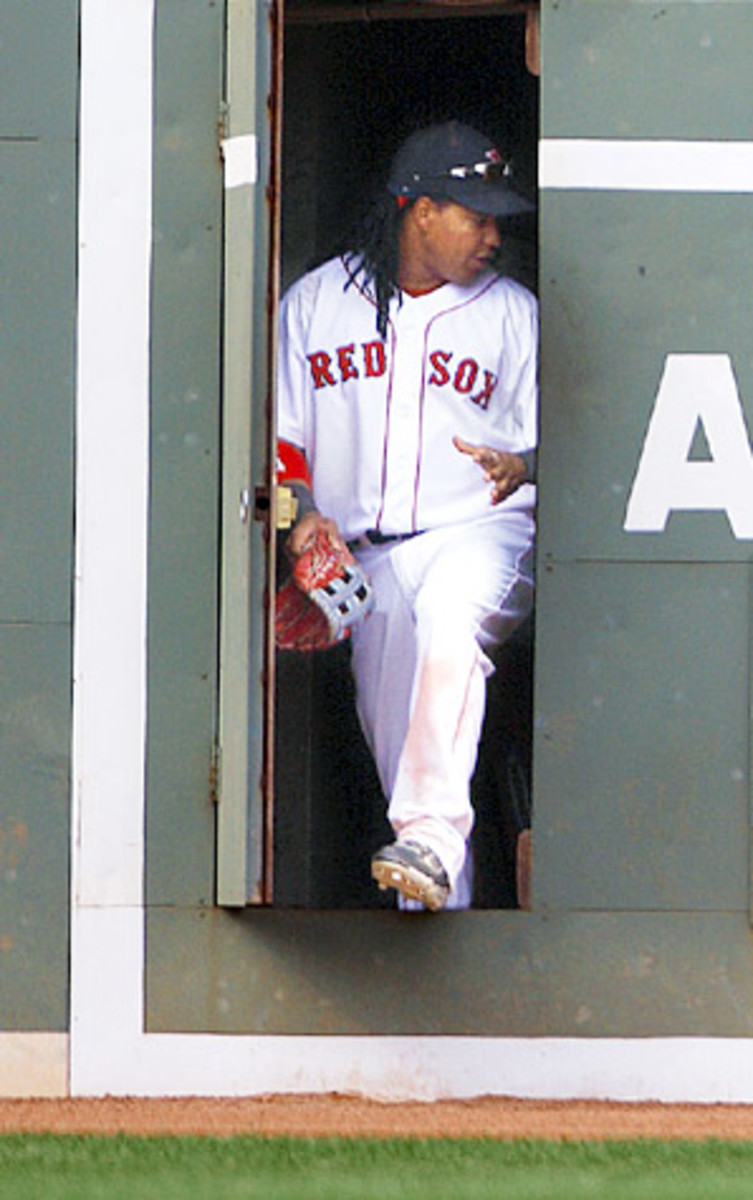

Indeed it was. Since bolting Boston last summer in a trade with the Dodgers, his trademark dreadlocks trailing him as he made a beeline for the laid-back world of Los Angeles, virtually all traces of Manny have vanished from the Red Sox and the place he once called home. At the Yawkey Way Store across the street from Fenway, the only Ramirez items are an autographed ball ($300) and a pair of framed autographed photos. His No. 24 jersey, which once seemed as ubiquitous at Fenway Park as green paint, was nowhere to be found among the early-arriving crowd before Thursday night's game with the Indians. His locker in the clubhouse has long since been turned over to someone else. Yet for one day at least, Ramirez was a Red Sox again, as surely as he was during any of his eight entertaining, controversial and ultimately combustible years with the team, and the players he left behind were once again caught up in a Manny-created maelstrom.

"Obivoulsy, it's a big news story and blah, blah blah ... but he's not a part of our team anymore," said closer Jonathan Papelbon, who didn't hear the news until he got to the clubhouse.

David Ortiz, who had said in spring training that any player testing positive for steroids should be suspended for an entire season, initially balked about discussing the man with whom he will be inextricably linked in history for the slugging exploits that earned them raves as the game's most fearsome 1-2 punch since Ruth and Gehrig. "I play for Boston, Manny plays for L.A. Go ask him," he said, before adding, "It's a little confusing from what I've seen because there's guys out there taking things you can buy over the counter. Sometimes it's banned, sometimes it's not. I don't know. You've definitely got to be careful man."

Manager Terry Francona begged off any questions related to his former star outfielder, and general manager Theo Epstein didn't address the media (Indians general manager Mark Shapiro, who had been with the organization when Ramirez played there from 1993-2000, also had no comment). The Red Sox did release a memo that read, "In accordance with the Basic Agreement between Major League Baseball and the Major League Baseball Players Association, the club is prohibited from commenting on the specifics or the facts of the matter related to Manny Ramirez. Major League Baseball keeps these matters confidential, and as such we do not know any more than what was released by the league. We staunchly support Major League Baseball's drug policy and commend the efforts associated with that program."

"With the rules in place it kind of takes [commenting] off your plate," said Francona. "I am aware of what has happened today, but I also know that when you walk by the TV about the first thing you hear from everybody is 'well, I really don't know the facts.' When I don't know the facts, I don't need to be stating opinions."

Jason Varitek, Ramirez's teammate for his entire tenure in Boston, sounded a similar note. "Before you pass judgement, everybody needs to find out what's going on," he said. "I don't know how to react."

Mike Lowell did, admitting to being "absolutely" shocked by the news and said he had no knowledge of Ramirez using anything illegal when he was in Boston. "I don't understand why anyone would even come close to [taking] anything that could provoke a positive test," he said.

Bay said he was just tested the other day and that baseball's stringent testing policy and severe punishments are on his mind. "I worry about everything I take because of that," he said, adding that players have the chance to run any supplements or medications by MLB if they aren't sure whether they are allowable or nor. "Everybody in here, whether there's a 50 percent chance or a 1 percent chance [of testing positive] should look into it. If you're unsure, send it to MLB and they'll test it."

"They make a pamphlet in Spanish and English telling you what you can and can't take," said Papelbon. "It's not that hard."

What is hard, said Lowell, is "for major league baseball to glorify guys they think are doing it right because they don't know. It's another black eye for the game."

There was some concern that the news would be a black eye for the two World Series titles the Red Sox won with Ramirez, as well. Though it isn't known yet when Ramirez began taking the substance he tested positive for, or when or if he took other banned substances, the very notion that those titles would be tarnished seemed an especially bitter pill to swallow for the players who were there. "I have no idea," said Varitek when asked what impact this would have on those championships. Lowell dismissed the thought, saying "There were 25 guys on those teams."

The bigger concern now is the harm Ramirez has done to the game itself. There is no time machine, like the one in the movie Back To The Future -- which several Indians were watching before Thursday's game in the visitor's clubhouse -- that can go back and prevent the damage that has been done to baseball. Varitek tried to sound hopeful by saying, "This game is much bigger than the players."

There was a lesser concern that Ramirez's positive test may have blown his Hall of Fame chances. Red Sox broadcaster Dennis Eckerlsey, who was enshrined in 2004 and was wearing his Hall of Fame pin on Thursday, said that his general philosophy is to decide whether a player was a Hall of Famer before they were known to have used steroids. "But what do I know?" he said. "I know other Hall of Famers don't like it one bit." Asked who they would take their concerns too about letting a tainted player into their exclusive fraternity, Eckersley said, "We'd go straight to Bud," meaning commissioner Selig.

Ramirez had once been considered a certainty for Cooperstown. And for all the frustrations that often came with Manny Being Manny when his plaque was made surely it would come with that crooked smile, the flowing dreadlocks and, of course, a Red Sox hat. He would join a trio of Hall of Famers -- Ted Williams, Carl Yastrzemski, and Jim Rice (who was also at Fenway on Thursday but refused to speak about Ramirez) -- who had tread the same hallowed ground in left field, in the shadow of the Green Monster, as he had. The famed wall that Ramirez defended (sort of) with his glove and assaulted with his bat, that still bears dozens if not hundreds of dents from rockets Ramirez launched off it during eight years that had once been remembered blissfully, and now will be recalled skeptically.

If The Wall could talk, what it would it say? Perhaps that it has seen much in its almost century of existence. That the game that survived the stain of the Black Sox scandal and the sin of the color barrier, can ultimately survive the shame of the Steroids Era, which has lasted far longer than anyone hoped it would.

John Smoltz, who has seen much in his two-decade career that seems sure to end in Cooperstown, tried to sound optimistic that the dents the game has incurred in its own wall will one day be smoothed over by the powers that be, and the current and future generation of players. "I hope they clean the game up," he said. "Get it back to being the greatest game on earth. I think they will."