One of a kind: Konchalski cements legacy as evaluator, great mind

FOREST HILLS, N.Y. -- Early in the afternoon of May 23, 1980, Roy Williams, then a restricted-earnings assistant at North Carolina, drove talent evaluator Tom Konchalski to the Seamco Classic, a prep basketball all-star game, in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York. Two senior prospects -- Sam Perkins and Matt Doherty -- were there, but Williams was preoccupied talking about a junior. He referred to him as "Mike Jordan", estimated his height at 6-foot-4 and asked Konchalski whether he could enroll him in the Five-Star Basketball Camp. Jordan, Williams offered, could bus tables to pay his way.

Sure, said Konchalski, a tall, gentlemanly figure, in his calming voice. The previous five years he had worked the camp, and gained influence with its director, Howard Garfinkel. Konchalski explained that Howie would place a call to Cliff Herring, Jordan's coach at Laney High, about arrangements. He also suggested Jordan attend Session I at Robert Morris College outside Pittsburgh -- the camp's Cadillac week.

The Heels' not-so-invisible hand guided the guard to Session 2, thinking he'd fare better against that week's level of competition. Konchalski believed it also fit better into their schedule to show Jordan attention. Once on site, Jordan got any shot he wanted during tryouts, easily elevating over opponents. "Defenders were guarding his belly button," the scout said.

Konchalski starred the pony in his racing form. Typically, he would funnel such observations to inquiring coaches, but he was assigned to work with Syracuse assistant Brendan Malone's team that week. When Malone's wife, Maureen, was injured in a moped accident and held overnight at a hospital, Malone rushed home to Rockville Center, N.Y. to be with her. Konchalski, who had no coaching experience above CYO, was charged with selecting their team. Malone left suggestions.

Upon his return for breakfast the next morning, Malone asked Konchalski which pick they drew. "No. 1," Konchalski said, smiling.

"Great," Malone said. "You took Greg Dreiling?"

Konchalski nodded. He had selected the Wichita, Kans., center.

"Then Aubrey Sherrod?" Malone asked.

"No," said Konchalski, who passed on the Chicago teammate of a young Doc Rivers. "I took Mike Jordan."

Malone's mood changed. He had known Konchalski as a "ubiquitous basketball maven" and grown to respect his word. The previous two years, though, the bird dog recommended players who never showed up. "Who the f--- is Jordan?" Malone asked.

By week's end, Jordan shared Most Outstanding Player honors and was named all-star game MVP. "No one cursed out Rod Thorn for drafting him," Konchalski says.

Over the last four decades, Konchalski has discovered thousands of players, giving him the ear of top coaches. A lifelong bachelor who graduated from Fordham University magna cum laude with degrees in political science and philosophy, he has charted prep stars' progress and forecasted their futures. Now 63, his bone-thin, 6-foot-6 silhouette is as familiar in bandbox gyms as Coca-Cola scoreboards. NBA rosters read like yearbooks to the self-employed editor and publisher of High School Basketball Illustrated. "He's basketball's Kevin Bacon," says Manhattan coach Barry Rohrssen. "Everyone connects back to him."

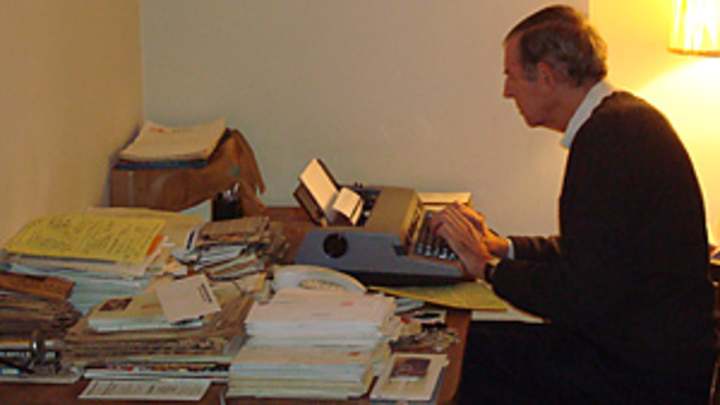

In the age of recruiting Web sites, Konchalski is the iconoclast. He introduces himself to each player he evaluates with a tourniquet handshake and wrings out 15 annual reports on his25-year-old typewriter. He charges the 200 schools that subscribe to his service -- ranging from Division I to junior colleges -- $375. He addresses each envelope in black ink before mailing.

His operation has mom-and-pop elements. Having lived at home until he was 38, his mother, Marjorie, often answered the phone and took messages from coaches while he was at games. When she died in 1984, he went without an answering machine. Finally, for six months in 2003, he installed one. The tape filled quickly. Coaches, accustomed to using his bespectacled eyes as looking glasses, wanted input, but he could not fall asleep knowing there were unreturned calls. He permanently unplugged it. "He's the single toughest person in the world to reach," Louisville coach Rick Pitino says.

Konchalski holds onto everything (stats, phone numbers, movie lines) yet has not grasped the need to use a computer, cell phone or drive a car. He buys ribbons from the same midtown Manhattan salesman he purchased his typewriter from in 1984. "I'm a dinosaur in that store," Konchalski says.

His memory is eidetic. Garfinkel once showed him a photograph with eight players going for a rebound. The lens also captured a tattooed arm. He named all eight and the arm's owner. "He knows 'this kid's dentist is so-and-so; he was delivered at birth by this doctor'", says former Seton Hall coach and CBS analyst Bill Raftery.

Konchalski, a southpaw, curls his writing hand around yellow legal pads from the last row of bleachers in most gyms. Thirteen categories (points, rebounds, dribbles, penetrations, etc.) occupy his mind. "He has his own shorthand so no one will steal it," says Jack Curran, who coaches his alma mater, Archbishop Molloy (Briarwood, N.Y.).

Hoops absorb him. He hasn't exercised consciously since 1983, been on a beach in 32 years or ever left North America. He caught heresy in Doubt, a movie based in fall 1964, when Mrs. Miller walks with Sister Aloysius past a playground. A three-point line is visible on the blue-and-red concrete. Apoplectic, he says, "the line was not even conceived of then!"

While characters ranging from outliers to liars dot the recruiting trail, author John Feinstein refers to him in The Last Amateurs as "the only honest man in the gym." "There are no skeletons in his closet," Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski says.

But there are yellow legal pads. More than 8,000 pages, sans binding, sit on a shelf in apartment 19D in his doorman building off of Queens Blvd. "His life is like a tapestry woven with players," says Eddie Broderick, a longtime friend.

One thread extends from Jordan to Kobe Bryant. Before the 1995 McDonald's All-American game in Pittsburgh, the participants -- including Bryant -- watched a taped video message from Jordan, who ended, "I hope all of you reach your NBA goals someday. I'll be waiting and I'll be ready."

Jordan then winked at the camera.

Konchalski later spoke with Bryant at the awards banquet. The 17-year-old told him, "I can't wait to face the world's best." Bryant paused and said, "I'll be ready." He then winked.

*****

Step inside. The white walls in Konchalski's apartment have no photos or posters. The black marble composition notebook on the top shelf of the walk-in closet has a correction on its cover. When purchased in 1962, "English" was written on the subject line. Now it's scratched out and reads "Basketball." Inside are lined pages with yellowed newspaper clips between them. Headlines above black-and-white photos include: "Alcindor to Visit UCLA".

"These are my Dead Sea scrolls," Konchalski says.

His obsession started young. In 1955 he took his first trip to a smoke-filled Madison Square Garden for a Knicks game. The next year he returned to see St. John's. He was a player of modest talents, pretty good at three-on-three in the P.S. 102 schoolyard but he never tried out for an organized team. His father, Steve, a reticent, sports-mad general foreman in the department of parks and recreation, took him and his older brother to leagues across the city. At the Brownsville Boys Club they saw a teen palm rebounds with one hand. It was Connie Hawkins. Konchalski, then in grade school, had his first idol. "I didn't pretend to be in the same universe," he says.

One overcast afternoon in 1959, Konchalski walked to the fenced-in court at P.S. 127 to watch games between New York and Philadelphia teams in the Ray Felix Summer League. Hawkins, so poor he played in white clam diggers, blocked a shot and bodied a larger opponent into a fence during the prep contest, but a pro-game player left an even more lasting impression. Wilt Chamberlain, fresh off a tour with the Harlem Globetrotters, wore a denim hat that made him look like J.J. Walker in Good Times. In the second quarter there was a jump-ball between Chamberlain and a 6-1 guard. Chamberlain leaped and tapped the ball in. Thirty seconds later a cloudburst sent 1,200 fans scurrying out of the wooden stands. "God said, 'Nothing can top this. I'm ending it now'", Konchalski says.

He was just a fan then. The first person he ever evaluated, he insists, was himself and he "failed." In reality, he began judging people at 13. He wanted to be a ball boy at the West Side Tennis Club, but was too young for working papers. His uncle, John Coleman, the chief of umpires, suggested he work as an unpaid linesman. "Isn't that Tom, though?" says Xaverian High coach Jack Alesi. "The ball's in or it's out. A player's good or he's bad. No gray areas."

Fuzzy yellow balls landing on white lines at speeds in excess of 100 mph blurred the process. During a John McEnroe match in 1977, Konchalski called a ball out. McEnroe, the prince of petulance, complained and Konchalski reversed his call. After the match, a linesman told Konchalski he was correct originally. He never worked another match.

Basketball was a different story. Konchalski's curiosity knew no neighborhood limits, crossing city racial boundaries to watch the best. He and his brother heard fans at Rucker Park call out to Bill Bradley, "Show us what you got white boy!" Intimidating stares came their way. "We were in the minority in a lot of places," says Steve Konchalski, "but they respected that we wanted to be there."

Utopia was a seat in the stands. Tom watched Steve shoot his way to Acadia College in Nova Scotia, where he won a national title in 1965. Meanwhile, Tom stayed local, coaching CYO and reading philosophy on the long train commute. He considered studying for his Ph.D., but became a grammar school math teacher. Eight years in, he lost motivation to return to school for Greek and Hebrew studies, eschewing his doctoral path to work on Garfinkel's bible: High School Basketball Illustrated.

Not even Garfinkel has entered Konchalski's "inner sanctum." He moved into his current apartment 19 years ago after his mother died and his siblings decided to sell their childhood home. His brother, married with two girls and a boy and coach of St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia the last 34 years, is now known as the "Coach K of Canada." Last Thursday, he reached the most wins in Canadian history (736). He owns a cell phone and reads about American hoops on the Web. His sister, Judy, lives in Pittsburg, Kans., with her son and works at a Wal Mart. Tom Konchalski's life's work sits on the wood-topped folding table overcrowded with brittle newspapers, outgoing envelopes and his typewriter.

There's a window into his past in the living room. When he opens the blinds, there, in verdant Forest Hills, stands the West Side Tennis Club. Hofstra coach Tom Pecora says, "His world's like The Land Where Time Stood Still."

*****

"Ladies and gentlemen," Konchalski says. "Welcome to the City Game."

The man in the navy blue sports coat and maroon tie is your host, announcer and statistician on this night. He has vetted the 20 players on the rosters, making sure each has a 2.0 GPA and no official offers from schools. The 39th annual game is really a bargain bin for recruiters looking to fill out their rosters late in the calendar. It is April 21. Next to be introduced in the John Jay College gym is Patrick Parker, a 6-1 guard from Hillcrest High. Konchalski adjusts his microphone.

"His first name may not be Peter, but this Parker plays spider-like defense."

Garfinkel, sitting at the scorer's table, three chairs down from Konchalski, says, "Tom and I always loved our liners, but you know we started out as enemies, right?"

Konchalski irked Garfinkel. Mike Tyneberg, the man who brought Garfinkel into basketball and had since had a falling out with, would appear with Konchalski at New York Nationals games in the late '60s. Garfinkel, working with the New York Gems summer team, would glare at them. The stares went on until Dick Maloney, scouting for Holy Cross, broached a truce in 1970 when he brought Konchalski to Five Star. Three years later, Konchalski was handing out MVP ballots. "He was better at face-to-face evaluating than back-to-basket teaching," Garfinkel says.

To be at Five Star in the '70s was tantamount to watching flyboys at Edwards Air Force Base in the '50s. Each player was a hot shot proving his wares against the nation's best. Lectures stirred the groups as Hubie Brown, Rick Pitino and many others spoke. Konchalski, typically standing in a corner, took in the "para-religious" events.

Storytelling extended past the court's sidelines and Konchalski, the straightest piece of string in Queens, proved capable of spinning yarns as well as any Runyon character. "He loved to be like the good cop kicking around with the mob," Pitino says.

No tale was more unlikely than the union of Konchalski and Garfinkel. "If there were guns, one of us would've shot the other," Konchalski says.

Garfinkel had a tendency to fall in love with players' games, but Konchalski proved more modest. His economy of praise fell in line with his favorite moralist C.S. Lewis' thoughts: "Don't say 'infinitely' when you mean 'very'; otherwise you'll have no word left when you want to talk about something really infinite."

The Konchalski brothers were about academics first. Steve earned his law degree before coaching. Still, he wanted to know how long Tom intended to rate teens. Steve questioned this in a call to Curran: "Can you please tell my brother to get a real job?"

Change was an allergy, and the stubborn Konchalski sneezed at it. In 1976, Garfinkel had hepatitis and only got one issue out. The recruiters would call, and the two bachelor bird dogs would bark out their thoughts. "You prepared carefully to get them," Krzyzewski says.

They were colorful: "He shoots more bankers than Bonnie and Clyde", "jumps so high he says hello to God three times" and "he scores like we breathe."

Garfinkel agreed to return to print in 1981, but put his pen down in 1984 when he sold his share to Konchalski for a "very nominal fee", but the two still sit side-by-side at several games per year. Ever loyal, Konchalski has remained Garfinkel's teleprompter, refusing to even change the publication's name despite the fact that only the first issue was a glossy-page photo booklet.

Last October, the odd couple's roles reversed at "The Clinic to End All Clinics." Pitino, John Calipari and Brown each spoke in a Five-Star reunion of sorts. After Pitino finished, Garfinkel spoke, "If anyone has seen a black binder, please return to the front."

From the outside, everything appeared to be in order in Konchalski's neatly-arranged world. He had eaten a blueberry muffin for breakfast, as he always does. His increasingly gray hair was combed and gelled, left to right. His golf shirt was buttoned to the top, like a schoolboy on his first day. His rosary beads were in the right side of his shorts; the San Damiani cross was in the left.

Something was amiss, though. He looked like Linus without his blanket. The pale Polishman's complexion reddened. His legal pad, Metro Card and a 50-cent black Bic pen were in the worn binder, which was nowhere to be seen.

Down stepped Bridgeport coach Mike Ruane, who accidentally took the pad at the sign-in table.

"I felt naked," Konchalski said. "My pad's my fig leaf."

*****

Dennis (Mo) Mlynski's father, Joe, worked days as a machinist in the same drill press for 38 years. Mike Krzyzewski's dad, William, labored nights as an elevator operator. The boys from the northwest section of Chicago in the 1960s would go out for pizza on weekend evenings, and Mylnski would give his friend a lift. In July 1994, the Duke coach called his friend and asked for a ride -- not for him, but Konchalski, blowing through the Windy City. "Forget about Driving Miss Daisy," Duke's Krzyzewski says. "Let's do Driving Tom Konchalski."

Hop in. Storm clouds cover the New York sky on a Tuesday in July and Konchalski is riding shotgun to a summer league in Beltsville, Md. Before he gets out of Brooklyn, the borough of churches and players, he's lecturing: "The most amazing thing to me, rather than skyscrapers, is the transportation system. It's mindboggling to me."

Five subway lines, a bus stop and the last taxi cab stand in Queens are within three blocks of his apartment, but he remains a self-confessed pedestrian. Friends call him "The Glider" for his penchant to appear places without leaving a carbon footprint.

His longest car ride lasted 12 hours. It was summer 1978 to the 17-under AAU national tournament was at Marshall University. At the 9 a.m. game, a spindly guard from Chicago's South Side named Isiah Thomas cut through the Riverside Church's defense for 37 points. "I never saw so many people end up on the floor, foul line-to-foul line, trying to guard somebody," he says.

The day was still young. Konchalski hopped a ride 290 miles northwest to Akron, Ohio, to see forward Clark Kellogg play and then came back. They drove nine hours to see 45 playing minutes. "Well worth it," Konchalski says.

Basketball America welcomes Konchalski everywhere. Fletcher Arritt, the coach at Fork Union (Va.) Military Academy the last 40 years, refers to the guest room in his house, set on a bluff 90 feet above the James River, as the "Tom Konchalski room." "Still, he's never given one of my players a five-star rating," Arritt says.

Oak Hill Academy (Mouth of Wilson, Va.) coach Steve Smith adds: "Tom needs just two possessions to tell you what level a kid should be playing at. He's never been off with one of my kids."

He's crashed on coaches' couches, shared meals and gossip at diners, but it was the first assistant he met who impressed most. Aberdeen, the balding man who brought his brother to Canada, had migrated to Knoxville, Tenn., as a graduate assistant in 1966. While there, Tennessee's top assistant died in a plane crash. Aberdeen ascended. Konchalski explains his charm: "If you had someone come from France who was fluent in English but knew nothing about basketball culture, and you put them in a room with and told them to observe and listen to Bob Knight, Dean Smith, Hubie Brown and Stu [Aberdeen], for an hour on their topic choice, then said one of these men is fabulously successful, I guarantee you they would have said Stu."

Konchalski assisted Aberdeen, showing up at games on Tennessee's behalf. Garfinkel mockingly called him "Tennessee Tom", but, in truth, he was The Ultimate Volunteer, assisting in the recruitment of Ernie Grunfeld, whom Konchalski saw play in his first CYO game. Grunfeld, who chose Tennessee, says, "My parents listened to him because they trusted him."

Bernard King crowned Konchalski's legacy. Konchalski approached him after an all-star game in Hoboken, N.J., and recommended Tennessee offer the underrecruited overachiever. Twenty-five days later, the Vols, going on the blind word of Konchalski, landed the greatest forward in school history.

Aberdeen felt indebted. Konchalski did not want anything, but there was this Molloy senior. His name was Joe Dunleavy. He had first seen him in CYO, wearing a flannel Mets jersey and taking a layup off the correct foot. He couldn't afford college, and wasn't good enough to play. Could he be on scholarship as a manager? "Stu said to me one day, 'Your friend Tom is as close to a saint as you'll see'," says Dunleavy, who attended Tennessee and earned his degree in physical education.

Some stories sound like fairy tales. In 1986, Konchalski caught a whooping case of Hoosier Hysteria, a year before Hoosiers hit the big screen. The next season he arrived at Hinkel Fieldhouse before anyone collected admission at the door for the state title game. Inside, a janitor measured the rim's height, just as in the movie.

The road never shortens. As busy as accountants are in April, Konchalski is busier in July. On this night, he watches DeMatha (Hyattsville, Md.) play rival St. John's. Quinn Cook, a rising junior goes for 15 second half points, all of which Konchalski charts.

Page numbers read like an odometer. This is page 8,051. He lingers afterward, greeting coaches. Bob Wagner, who coached Len Bias, at Northwestern High (Hyattsville) asked. "Do you have a driver's license?"

"No," Konchalski said.

Wagner laughed. "You're nothing but a one-night stand down here."

*****

The country boy from Catoosa County, Ga., was born with springs in his calves. As a junior at Ringgold High in 1972, David Moss cleared 6-10 in the high jump. He twice won states in the event, but his future was basketball. Parade magazine named him a fourth-team All-America and Tennessee signed him by the time he played in the 1973 Seamco Classic. Konchalski noted his strength. "The firmest handshake I've felt," he says.

Moss's legs were his most powerful assets, but one left him early. His freshman year in Knoxville he was diagnosed with bone cancer in his right leg. It was amputated at the hip. He survived six and a half years, and the Seamco Classic, which invited him back each summer, donated money to charity. Konchalski prayed to St. Peregrine, the patron saint for cancers of the bone.

You endured painful sufferings with such patience as to deserve to be healed miraculously of an incurable cancer in your leg by a touch of His divine hand ...

"My heroes are my mother, Mother Teresa and David," Konchalski says.

The meditation, which he recites daily, comes easily, but putting names to intentions demands stronger focus. When a family member of a player, coach or referee he's encountered in his travels falls ill or passes, he makes room for them in his alphabetical list, offering up what is now a 12-minute long reflection.

He's become the game's keeper, a breathing obituary overflowing with dates and anecdotes. Hospitals, hospices and funeral homes are common haunts. Three-to-four times per week he attends mass at Our Lady Queen of Martyrs, around the 12th row, altar left. On holidays he visits with friends suffering from illnesses as dire as terminal cancer. "Tom must have stock in Hallmark," says Davidson coach Bob McKillop. "He projects uncommon compassion."

Moss lives in each greeting. Konchalski's handshakes double as history lessons, putting things in perspective for a landscape forever hurrying the old off the stage for the new to arrive. St. Anthony (Jersey City, N.J.) coach Bob Hurley diagrams it like a defense: "You have to go in wide and quick so he doesn't pin you on contact."

Few hold on longer than Konchalski. After the Jordan Brand All American Game at Madison Square Garden last April, he carried his worn binder in his left hand and made his way toward the locker rooms -- his 34th season now in the books. Oklahoma City Thunder forward Kevin Durant -- still baby-faced and wearing a blue-striped shirt -- walked past the prep players. As he sidestepped agents and their runners, the 6-9 Durant approached Konchalski, who first saw him as a stringy sophomore at National Christian in Fort Washington, Md., six years earlier. Garfinkel stood to Konchalski's right.

"Mr. Konchalski," Durant said, "so nice to see you."

He extended his hand and shook it.

"Two years in the league," Konchalski said, still shaking. "It's like you're a veteran already."

Durant deferred that title, saying, "Almost, almost."

The vise grip loosened after 20 seconds and Durant walked away, smiling.

"That's respect," Garfinkel said. "Kids realize when they've moved on that Tom could be curing cancer with his mind and talent, but it's really worth it when you see the lives he's touched."