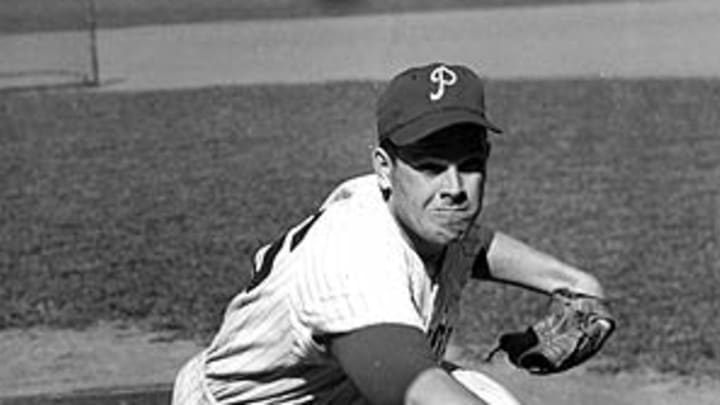

Robin Roberts was proud of his successes as well as his failures

A few years ago, I came home and found a message on the answering machine from someone who claimed to be Robin Roberts, the Hall of Fame pitcher. The person was calling because he had read some of my work, and he liked it, and he happened to be in Kansas City to see his brother and he wanted to meet me at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum so he could tell me some baseball stories.

My first thought was that it had to be a put-on. Hall of Famers don't just call up sportswriters they don't know because they want to chat. But I also had to admit that I didn't quite get why anyone would pretend to be the pitcher Robin Roberts (as he had to be known so as not to be confused with the television anchor Robin Roberts). And then, I had to admit that I really didn't know that much about the pitcher Robin Roberts.

I did a little research. The thing that jumps out at you when you look back at Roberts' career are the complete games. From 1950 through 1956, Robin Roberts started 37 or more games and completed more than 20 games every season -- that's Deadball Era stuff. Roberts led the league in starts six straight years, in complete games five straight years, in innings pitched five straight years, in victories four straight years. He was, in those days, a force of nature. Put it this way: He threw 28 consecutive complete games in 1952-53, and he was so enraged when he got pulled after seven innings against Brooklyn* -- Bums Send Roberts To Showers! -- that, for perhaps the only time in his career, the genial Roberts refused to talk to reporters.

*It was July 9, 1953; to give you an idea about the time, that was the same day that Ted Williams announced that he would play for the Red Sox in 1954 (if they wanted him), one day before Ben Hogan won the British Open at Carnoustie and the same day when a reported shortage of barbers sparked the trend story that more and more men planned to cut their own hair.

There was no Cy Young Award then, but in the six years leading up to the award -- 1950-55 -- Roberts received some serious MVP consideration. Here's how he ranked in MVP votes among pitchers.

1950: 2nd, behind only teammate Jim Konstanty

1951: 5th

1952: 1st; finished second overall, 15 points behind Cubs outfielder Hank Sauer

1953: 2nd, behind only the Braves' Warren Spahn

1954: 2nd, behind only the Giants' Johnny Antonelli

1955: 1st

So, he probably would have won two Cy Youngs in his prime, and maybe more.

The prime years and innings took their toll on Roberts, who was rarely a great pitcher after 1955. He had a losing record the rest of his career and a league average ERA. But he had already made his mark. Few in baseball history threw harder than Roberts did in those overpowering years. Bill James has guessed that Roberts probably threw in the upper 90s, topping 100 sometimes. And he pounded hitters with that fastball again and again, nine innings at a time, sometimes more than nine*, whatever it took. A force of nature.

*Roberts threw 21 games of 10 innings or more -- he threw 17 innings in beating Boston in 1952 and 15 in beating St. Louis in 1954.

One other thing about Roberts' career that you should know -- he gave up home runs. Five times he led the league in home runs allowed. The 505 homers he allowed in his career is the all-time record -- at least until Jamie Moyer , who is just seven behind, breaks it sometime this year. The funny thing, as you will see, is that Roberts was oddly proud of that home run record; he was proud of everything he did in the game. Hey, giving up home runs was part of his style -- you are supposed to challenge the hitter. Roberts didn't walk many. Sometimes he won, sometimes you won. That's baseball.

Anyway, I called back the number left on the machine, and, of course, it really was Robin Roberts -- it would not be much of a story if it wasn't. We met at the museum that evening ("Here I am!" he said when I first saw him). We walked around the museum for a couple of hours, looking at the various photographs and exhibits, and I listened to Robin Roberts tell stories. He was 77 then and remembered everything. I will cherish that night for the rest of my life.

What was it like? Roberts saw a photograph of Satchel Paige, and he remembered that he had once faced Paige in a barnstorming game. Roberts wasn't exactly a great hitter -- his lifetime .167 average is dead last in baseball history for anyone with more than 1,500 at-bats -- but he had grown up believing that he would be an every-day player, so much so that he was a switch-hitter. And Paige showed him no respect. He was toying around with him and threw him some sort of eephus pitch. Roberts lined a single to center.

What he remembered most, though, was going up to Paige years later and telling him about that hit.

"Roberts," Paige said back, "I got a big black book of all the great hitters who got a hit off me. And you ain't in it."

All the stories Robin Roberts told me that night were like that: self-effacing, funny, warm, touching. He talked about the first time he saw Willie Mays hitting in a batting cage and how he saw Mays blast home run after home run into the upper deck. And he thought, "Well, here's something new." He talked about the consistent grace of Hank Aaron and his old teammate Brooks Robinson. He talked about what it was like to have Luis Aparicio and RichieAshburn making great plays behind him. I remember that we went into the small theater to see the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum movie, which begins with a young man singing The Star-Spangled Banner. Roberts stood up and put his hand over his heart.

At one point, he saw a display for Jackie Robinson and he told me two of my favorite stories, both revolving around Robinson. One was about Robinson. One, I think, was more about Robin Roberts.

The first story was about the Whiz Kid Phillies of 1950. While people often talk about the collapse of the 1964 Phillies, they tend to forget that the 1950 Phillies tried to do it first. Those Phillies were up 7 1/2 games on the Brooklyn Dodgers on Sept. 20. They were still up five games a week later, on Sept. 27. But then they lost five straight games, and that Sunday they had to beat the Dodgers in Brooklyn or be forced into a playoff. Roberts was 24 years old and was sent out to lead the Phillies to their first pennant in 35 years. He was pitching on two days' rest.

He pitched 10 innings. The only run he allowed was on a Pee Wee Reese home run. Roberts worked his way out of a bases-loaded jam in the ninth -- thanks in large part (as Roberts himself said) to a perfect throw by Ashburn to nail Cal Abrams at the plate. He also led off the 10th inning with a single... that eventually led to Dick Sisler hitting a three-run homer. Roberts finished things off in the bottom of the 10th, and the Phillies won the pennant.

After the game, Roberts was sitting there on his stool, champagne dripping from his hair, when he felt a strong hand on his shoulder. He looked up. It was Jackie Robinson. "Congratulations," Robinson said.

"Think about that," Roberts told me. "Think about how much class that took. I couldn't have done it, I'll tell you that."

Of course, Robin Roberts would have done it. He was like that. And that leads to the second Jackie Robinson story. In 1951, everyone remembers that the New York Giants came back from oblivion to catch the Brooklyn Dodgers and then beat them on Bobby Thomson's "The Shot Heard 'Round the World" home run. What many people don't realize is that the Dodgers actually had to win their final two games against Philadelphia just to force that playoff. They beat Roberts 5-0 on a Saturday. But the Sunday game was quite a different story.

In the Sunday game, Robinson started off terribly. He hit into a double play, booted an easy ground ball that allowed two runs to score, took a called third strike, threw wild on another play. He would make up for it. In the eighth inning, the Phillies led 8-5, but the Dodgers pulled within a run. And Roberts was put into the game even though he had pitched the day before. He gave up a single to Carl Furillo that tied the score.

Then, Roberts pitched five gutsy scoreless innings. It looked like the Phillies were going to win in the bottom of the 12th inning -- they loaded the bases and then Eddie Waitkus lined what looked to be a sure single up the middle... so sure that Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe began to walk off the mound in disgust. Instead, Robinson made a diving catch just inches off the ground -- so close that there were Phillies fans who remained certain decades later that he did not catch it. Robinson hit the ground so violently that play was stopped for five minutes as he regained his breath.

Two innings later, with curfew just a shade of dark away, Robinson hit a home run off of Roberts to give the Dodgers the lead and force the classic playoff with the Giants. Robinson would call it the biggest hit of his career.

You may have already known all that, or at least the basics of it. But what struck me that day in the Museum was how Robin Roberts remembered it. He was, well, proud of it. He was proud of his whole career. He pitched hard. He gave his all. And Robinson beat him. No shame in it. Sometimes he pitched the game-winner. Sometimes he gave up the big home run. And it was all part of his beautiful journey in baseball.

"If I don't give up that home run to Jackie," he told me, "there is no Bobby Thomson home run. There is no playoff. It's a good thing I gave up that homer to him, isn't it?"

And then, he smiled: "Of course, one thing I could do was give up home runs."

That's how I remember him. That smile. That humble line. Robin Roberts died on Thursday at his home in Florida. He was 83 years old. I had talked to him a few times since we met at the museum, and he was always the same: Humble, kind, eager to avoid hurting anybody's feelings. He lived a big life. He was in the Army air corps. He was a star college basketball player at Michigan State. He was a great big league pitcher. He was one of the pioneers of the baseball players association -- he, along with Jim Bunning, pushed for the hiring of Marvin Miller. He was deeply involved with the Baseball Hall of Fame. He has had his number retired in several places, and he is in numerous Halls of Fame, and he has had a stadium in his hometown of Springfield, Ill., named for him.

But I still tend to remember him most as the modest man who could not help being proud of the home run he had allowed to Jackie Robinson, the one that set up perhaps the greatest moment in baseball history. "You want to be proud of your successes," he told me, "but you want to be proud of your failures, too. The important thing is try hard." And Robin Roberts always did.