Sometimes you really need to look beyond MMA's hype

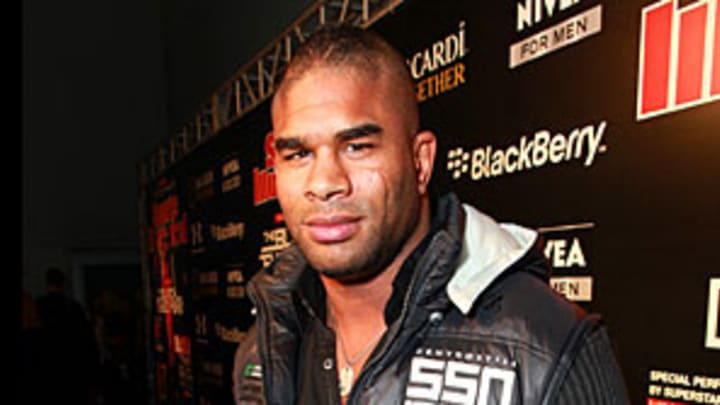

Oddly, no one dropped a gloating note after Overeem defeated Fabricio Werdum, one of the five best heavyweights in the world, this past Saturday. They might have, but they didn't, most likely because the way he won validated every criticism that every skeptic has made. (I actually came out of the fight thinking better of Overeem than I had previously, but results matter a lot to me.)

The most basic critique of Overeem is that he hasn't, past week aside, faced any legitimate competition in years. This is a problem not because, once you set a giant computer whirring, his record comes up short, but because there are elements of high-level fighting for which you can't really train. Facing true peers takes you into deep waters, mentally and physically. It tests the way you react to pressure. It tests your endurance and ability to plan a fight. Anyone who isn't tested regularly should be eyed warily.

Against Werdum, Overeem was visibly lacking in the resources you draw on when you've been working at the highest level. To his credit, he held his discipline, refusing to play in Werdum's guard until both men were so badly exhausted that Overeem just gave up and lay atop the Brazilian. He was also tentative and inflexible, with no obvious plan other than knocking his man out. He showed nothing on the ground, and proved that adding dozens of pounds of solid muscle has done nothing for his always sketchy conditioning.

He looked, basically, like a man out of time, a stand-up fighter who was frustrated that the rules allow tricky grapplers to avoid standing, and convinced that real men punch one another in the face.

This plays into the second main critique of Overeem, which is that his kickboxing accomplishments are irrelevant in MMA because the two are different sports. K-1 bouts take place in a ring between competitors wearing large gloves who don't have to worry about takedowns, and they have a distinct rhythm that's quite different from a mixed martial arts fight. Saying that Overeem's K-1 title counts for about as much as his golf score in a fight against Fabricio Werdum doesn't diminish the achievement of winning, it simply expresses a truism. A K-1 Grand Prix win didn't make Mark Hunt a great fighter and an Olympic pedigree hasn't made Dan Henderson a great MMA wrestler. Fighting is its own peculiar sport.

Last Saturday, you saw this, if you had eyes to see. Werdum was slipping quick combinations, landing in the clinch and flowing with heavy shots so as to avoid taking the worst of them. According to FightMetric, Werdum actually had the better of the standing game, landing one-third more significant strikes and total strikes. As much as anything, that's a testament to the current limits of quantitative analysis of a fight, since no one who saw Werdum flopping onto his back and praying or a squared-up Overeem landing his nastiest short hook would say that the striking was quite even. Still, Overeem failed to overwhelm a fighter with dubious standup skills and wrestling ability that is hardly so good that it would make a world-class striker gun shy. This was a powerful display of how very different kickboxing and MMA are, and how limited the application of one to the other can be.

(While my opinion doesn't much matter, Overeem also failed to excite UFC officials on Saturday night. I asked one what he made of the fight. "Not impressed with either guy," he said. "It was close but sad that Werdum outstruck him.")

In all, Overeem hardly looked like a world beater, partly because both he and his opponent were smart enough to fight to their strengths and ignore a crowd that was baying for blood, and partly because he has glaring holes in his game. He looked like a man who would get trounced by Cain Velasquez or Junior dos Santos, who would be susceptible to a quick knockout by Fedor Emelianenko or Shane Carwin, who would be pinned down and suffocated by a healthy Brock Lesnar, and who would have serious problems with Frank Mir. He'll likely have problems with Antonio Silva in the next round of the Strikeforce Grand Prix. Should it happen, a fight with Josh Barnett would be dangerous for him. Nothing that he did against Werdum made me think he hasn't been badly overrated, at least by some.

All of this being so, I'll break the sportswriting code and admit that I was just flat wrong to call Overeem a fraud. There are two Alistair Overeems. One is an exceptionally accomplished combat athlete who may or may not rate as one of the five best heavyweight fighters in the world. He has never showed himself to be anything less than willing to fight the likes of Emelianenko, Chuck Liddell and Shogun Rua, and he beat a very tough fighter this past weekend. The other Overeem is a contrived image of a hulking knockout artist that is being sold by a consortium of international fight promoters who are more interested in banking dollars than promoting high-end competition. That image deserves scorn, because it's false. The man deserves respect. I blurred the two, and shouldn't have done so.

This brings me to something that earned me many, many more angry e-mails than calling Overeem a fraud did, and that was defining the Penn Fallacy, which as I have it, occurs "when a fighter is thought of as top rank despite there being no evidence that he is."

This is of course a reference to B.J. Penn, who on his best day is about the most compelling fighter in the history of the sport, and who has spent his entire career answering questions about his dedication, his discipline and what he does when the bell rings on big fights.

No one, and this certainly includes me, questions that Penn is in some sense a great fighter. Rightly lauded as a jiu jitsu genius before he'd ever fought as a professional, he showed off unrivaled hands in his first three fights, landing three first-round knockouts and defining what it means to be a true mixed martial artist. A natural lightweight who could probably do fine cutting his way to featherweight, he choked out Matt Hughes -- at the time, the greatest fighter in the short history of the sport -- for a title in his first bout at welterweight. He went on to take Lyoto Machida to a decision in a fight held at heavyweight, draw out Georges St-Pierre to about as close a decision as there could be, run up a series of brilliant title defenses in the lightweight division, and do other impressive things. When committed and focused and fighting in his proper weight class, Penn is on the level of St-Pierre or Emelianenko or Anderson Silva, maybe even above them. He's about as talented an athlete as you'll ever see.

None of this, though, marks his legacy. In title fights, Penn is 5-5-1. He is 2-5-1 in what I would call the defining fights of his career: his first two title bouts against Jens Pulver and Caol Uno, his fight with Takinori Gomi, the first two Hughes fights, his two with St-Pierre, and a lightweight title rematch with Frankie Edgar, who outpaced him in a controversial decision in which Edgar was having his way with Penn by the end. There are cases here where you could say that he caught a bad decision, or was close and came into bad luck, but what has in the end defined Penn is his ability to not win when he could and perhaps should have, and his ability to avoid the natural consequences of that.

After relinquishing his welterweight title in 2004 to take freak show fights in Japan, Penn returned to UFC in 2006, was placed in a title eliminator against St-Pierre, and then, due to circumstances, got a title shot anyway even after losing the fight. After dropping two straight against Edgar, he was placed into another welterweight title eliminator on the strength of a win over a washed-up Hughes, despite not having had a significant win in the division in seven years and a 3-3 record in his last six fights.

Penn's record doesn't tell his story, and anyone who would deride him simply on the basis of seven losses and two draws against elite competition is a dunce, but there are sound reasons to think of him as something other than a truly great fighter. St-Pierre, Silva, Emelianenko, Liddell, Randy Couture and a few others are defined not by how close they've come to winning their major fights, but by actually winning them.

Partly because of bad luck and partly because of his own lack of discipline, Penn hasn't won at the crucial moments as often, and that counts. It doesn't make him a scrub. It doesn't mean that he isn't at a given moment a fight or two away from a title, and it doesn't mean that he isn't a marvel. It does mean that he is something less than a high exemplar of the sport.

As one trainer at a major camp told me in an e-mail, "The truth hurts sometimes. I'm a huge B.J. Penn fan, as am I a huge fan of Mike Tyson, Vitor Belfort, Rumina Sato and so forth. We see glimpses of excitement, charisma and greatness in these fighters, but eventually you look at the results and realize that maybe those moments or greatness were just that, moments; they fall short of ever actually reaching the heights it takes to truly be considered great. "

What I call the Penn Fallacy has, really, nothing to do with the man himself -- an admirable fighter, one of my favorites, who did more than almost anyone else to build a sport I'm lucky enough to cover -- than it does with his most delusional supporters. They pretend that none of this uncomfortable reality is true, that losses are victories, outcomes don't matter compared to what might have been in slightly different circumstances, that theory wins out over practice, and their man is the equal of fighters who did the dull work of cutting weight, training daily and winning fight after fight for years on end.

None of this matters on its own. Everyone is entitled to love their favorite athlete blindly. But it does matter in the broader context of MMA. This is a strange sport in which image can count for more than reality. Money and opportunities often go to the fighter who is best loved by the public rather than the one who most deserves them and shows it by simply winning the fights he's given.

If MMA is ever to reach its potential and become a more or less normal sport, results and achievement will have to matter a lot more than they do now. It's in the nature of a sport controlled by promoters and matchmakers that hype will sometimes win out over reality, and that has to be accepted to some extent. There is no mystery in the way Alistair Overeem has been promoted, or in why UFC hype shows dwell on B.J. Penn's highest moments rather than the many in which he wasn't quite good enough, or in why Brock Lesnar's third UFC fight was for the heavyweight title, or in why various subpar British fighters have been promoted as major contenders.

To understand, though, isn't to totally accept, and where frauds and fallacies make their way into the sport, they should be called as such. To do so isn't to disrespect fighters or the sport. If anything, the opposite is true.

Tim Marchman can be reached at tlmarchman@gmail.com