A wild ride with Wooden, Alcindor and the 1968 UCLA Bruins

SI.com asked several current and retired SI writers to offer reflections on the best team they ever covered as sports journalists. Here's Joe Jares on the 1968 UCLA men's basketball team:

In 1967-68, I was a 30-year-old, newly married SI writer along for a wild ride across the country with the greatest coach who ever lived, a phenomenal 7-foot, 1-½-inch center and an extraordinary UCLA Bruins team that took me from snowy West Lafayette, Ind., to the Astrodome in Houston to Madison Square Garden in New York and eventually to the L.A. Sports Arena while they took their sport to a new level of excellence.

Watching John Wooden, Lew Alcindor and the Bruins roll to the NCAA title that season -- their second straight and fourth in five years -- was made more delicious because the Bruins were not perfect. They actually lost a game, and not just any game, but a contest played before the biggest crowd in the history of the sport.

(Full disclosure here: I went to USC, UCLA's bitter crosstown rival, and was a starting forward on the 1955-56 frosh basketball team that lost four times to the "Brubabes." 'Did this cause me discomfort in covering Bruin triumphs? Not at all. I wanted to report on the big stories. Also, I'm not above sleeping with the enemy -- my wife is a UCLA graduate.)

The Bruins opened their season on the road at Wooden's alma mater, Purdue, which had a new, $6 million arena and a homegrown Hoosier hotshot sophomore named Rick Mount, who scored 28 points. UCLA squeezed by 73-71.

Under the usual deadline pressure, I wrote almost until dawn in my motel room. SI was one of the best-written magazines in America and I was expected to turn out not just top-notch prose but something as close to literature as I could get, or so I felt. It had snowed all night. I came out in the nose-numbing cold and found that the doors on my rented red car were frozen shut. I wiped the snow off the windshield and got water in my watch, ruining it. The motel clerk assured me that it hadn't been cold enough to freeze doors shut. Right. I had wiped off the wrong vehicle. My rented red car was parked a few feet down the row. I raced on icy roads to Indianapolis, filed my story with Western Union and barely made my flight.

Years later I told that story to Wooden in his cluttered den in Encino, Calif. It gave him a chuckle -- the ex-Martinsville, Ind., farm boy amused by the misadventures of a West Coast wimp.

The close call against the Boilermakers was the only real early-season threat to UCLA's winning streak. By January 20, the No. 1 ranked Bruins were 13-0 and had won 47 straight overall when they arrived in Houston to face No. 2 Houston, led by Elvin Hayes and an all-star cast of Cougars, in the Astrodome before, as I would later write in the magazine, "the largest crowd ever to see a basketball game in the U.S. ... and before the biggest television audience in the history of the sport" -- 52,693 fans plus viewers of 150 TV stations in 49 states. Two things conspired against the Bruins on that historic occasion. First, Hayes was sensational, scoring 39 points, grabbing 15 rebounds and making the two deciding free throws. Second, Alcindor had suffered a scratched cornea eight days earlier and had missed two games. Still, the Cougars won only by two 71-69.

SI VAULT:Hayes, Houston knock off the giants (01.29.68) by Joe Jares

Adding to the Bruins' troubles, senior forward Edgar Lacey, who was pulled after 11 minutes of the Astrodome game and never returned, quit the team and blasted Wooden. (Bad for the Bruins' image, no doubt, but the material remaining was formidable, including outstanding guards Mike Warren and Lucius Allen, and a forward with an awkward-looking but accurate corner jump shot, Lynn Shackelford.)

UCLA had lost on the road to an undefeated team. Nothing to be ashamed of, but some fans nevertheless blamed the Wizard of Westwood; the Bruin Hoopsters support group, according to Dwight Chapin in the San Francisco Examiner, "made it seem as if he'd committed a capital crime."

"You should have seen what they put that poor man through,'' a friend of Wooden's said. "It was as if they were asking him, 'Well, coach, what have you done for us lately?'"

Before resuming its league season, UCLA defeated Holy Cross and Boston College on successive late-January games in Madison Square Garden. New York City was Alcindor's hometown and he was thrilled to be back, on the short bus rides excitedly pointing out the sights to his teammates. When we journalists heard about this, it helped humanize this giant who had been kept under wraps.

Wooden was extremely protective and proud of the young man he usually called Lewis but that the world would later know better as Kareem. "Some say he's too thin," said the coach, "but he's heavy enough for me." At a coaching clinic in the Catskills in June of 1967, I heard him say, "You do not treat them (players) all alike. If we have only a few good shoes, I guarantee you Lew's going to have good shoes." He pointed out that his center could easily have led the country in scoring but preferred to share the spotlight and the ball with his teammates and win championships. He also pointed out that the rule makers had outlawed dunking just because of Alcindor (that actually didn't bother Wooden; he didn't like the dunk).

Wooden's locker rooms were not open to the press, an annoyance and an inconvenience to those of us with mikes and notepads -- and deadlines. Indiana's Bob Knight wasn't always the most welcoming fellow, but after games his players were by their lockers ready to answer questions. Knight felt it was part of their education.

The wall around Alcindor was lowered just a bit after his freshman year, when the school would not allow him to talk to reporters and vice versa. School officials even scolded the Los Angeles Times after one of its photographers took a picture of Alcindor attending a football scrimmage.

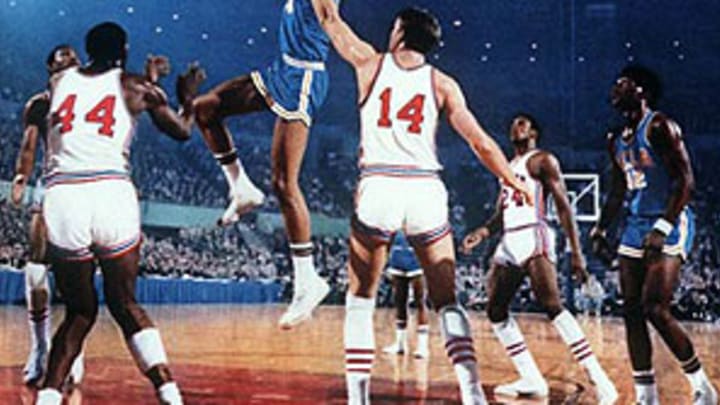

After the New York trip, UCLA won its next 12 games and earned its way into what was just becoming known as the Final Four, played in L.A. on the very same 18-ton, 225-panel floor that had been shipped to Houston for the dandy in the 'Dome. And better yet, played against the unbeaten Cougars and Hayes.

The enduring image in my mind from that game is Elvin sitting on the bench at the finish with a towel over his head, because UCLA got revenge in a big way, 101-69, what I described as "one of the finest exhibitions of skill, speed and shooting in the history of college basketball." On defense, UCLA devised a diamond-and-one scheme, with Shackelford dogging Hayes every second (Alcindor later wrote that Shack's performance "was one of the most dedicated, perfect defensive plays I've ever seen.")

(Premature congratulations: Four weeks before Hayes had been chosen player of the year and Houston coach Guy V. Lewis named coach of the year. The two weekly wire-service polls had ended before the NCAA Tournament, with Houston on top.)

Alcindor had taken the SI cover showing Hayes shooting over him in the Astrodome and put it in his locker, where it could bug him every day. (I had not taken that photo, but my story had been inside the issue. That's probably as close to the future Abdul-Jabbar as I ever got.) Lew finished with 19 points and 18 rebounds.

"That's the greatest exhibition of basketball I've ever seen," said Lewis of the rout.

Houston's ferocious live cougar mascot, Shasta, slept through the second half of the game. Another image that remains: junior Alcindor and senior Warren appearing after the rout in loose-fitting, multicolored African garments called "dignity robes."

The easy, 78-55 win over North Carolina in the final was anticlimactic. Tar Heels coach Dean Smith afterward called Alcindor "the greatest player who ever played the game" and UCLA "the greatest basketball team of all time."

SI VAULT:UCLA rolls to the title (04.01.68) by Joe Jares

Wooden said he agreed with the writers, me among them, who considered this team one of the greatest "in the history of intercollegiate basketball."

The Bruins were great, but they weren't always great to cover. Alcindor might have been intelligent, congenial and funny, but he and UCLA didn't let reporters -- even the ones who took the wild ride with them -- get close enough to find out.