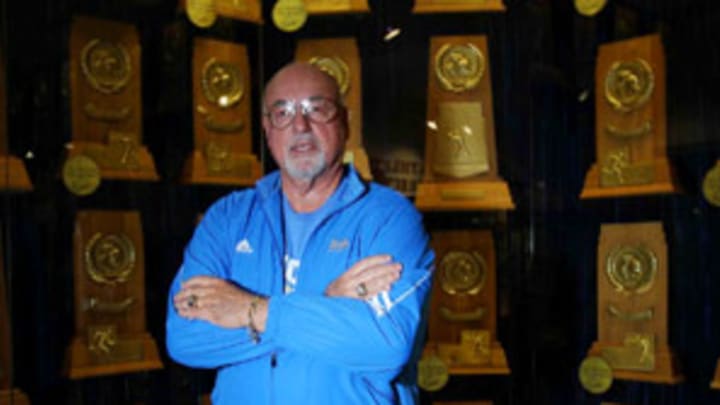

Legendary UCLA men's volleyball coach Al Scates shoots for 20th ring

One day last month Al Scates, the UCLA volleyball coach, was sitting in his den rhapsodizing about a favorite subject: his national championship rings. "I rotate them depending on how I feel," said Scates, 71. From a drawer in his cluttered desk -- a Coltrane CD, photos of a golf trip to Scotland -- he pulled out a pair. "This one, the 2000, is a little big, so it's good for flying, when my finger swells." He strolled to his bookcase, where rings lined up on a shelf, a glittering history of his 50 years as the Bruins' coach. "Look at '72," he said, plucking it from a velvet case. "It's so small now, it makes a nice pinkie ring."

After taking inventory at his home in Tarzana, Scates accounted for a dozen national championship rings. That's two more than the haul of another UCLA legend, John Wooden, but not even close to Scates's total. His 19 titles are the second-most ever among college coaches, trailing only the 20 of North Carolina women's soccer coach Anson Dorrance. Whither the missing bling? "Through the years a lot of my ball boys invited me to their bar mitzvahs," Scates said, "and I didn't feel like looking for a gift, so I'd give them a ring. I wasn't worried, because I knew I'd keep winning more of them."

Scates' confidence -- "as strong as cologne," says John Speraw, a former Bruins player and assistant coach -- has rubbed off on this year's squad, a largely unheralded bunch that has spent much of this season atop the polls. The Bruins' 22-7 record has pushed Scates's career mark to 1,239-289 (.812), which includes undefeated seasons in 1979, '82 and '84. This is his final year of coaching, and as the Bruins begin postseason play on Saturday, their mandate is to get Scates one last ring, giving him one for every finger and toe.

"There's a ton of pressure," says senior setter Kyle Caldwell. "We want to do it for Coach, we want to do it for ourselves, but we also want to do it for all the guys who came before us and built this program."

Scates is not only the sport's most prolific winner but also a pioneer who has shaped the way the game is played, a missionary who has spread it to unlikely places and a steward who has helped write the rule book. This season's farewell tour has been a chance for the volleyball community to pay its respects, and at every UCLA road game Scates has been feted with standing ovations and gifts from the host school. "This is my seventh year coaching against him, and I think I'm finally comfortable enough to walk up and begin a conversation," says UC San Diego coach Kevin Ring, 41. "I'm not sure any coach at any school in any sport has ever embodied winning the way Al does."

Scates wears his stature comfortably. After home matches he lingers to chat with fans and alumni, and he is solicitous of the most junior Daily Bruin staffer. He could once fill a gym with his hollering, but now he spends most of the time muttering salty asides to his lieutenants. ("Thank god he isn't miked," says assistant Brian Rofer, '80.) Mike Sealy ('93) compares Scates to the Godfather, but a new titanium left knee has left him with a bowlegged amble that evokes John Wayne. When he stands up to quietly address his team or chat with the linesman, every eye in the gym follows him. "Sometimes I think people stop breathing," says sophomore outside hitter Gonzalo Quiroga, who came from Argentina to play for Scates. "Of course everyone knows what he has done. But the respect also comes because we can see he is still burning to help us win."

Players and assistants have grown accustomed to receiving e-mails from Scates at 4:30 a.m., when he is already watching film. This year, for the first time, he is meeting with his staff after every match, no matter how late it goes. Following last month's sweep of UC San Diego at the John Wooden Center, Scates repaired to his small office, whose walls are covered with photos of his championship teams, one of which included a half-dozen Olympians. Crowding around were Rofer, fellow assistant Greg Harasymowycz and unpaid volunteer assistant Sinjin Smith ('79). (Smith and Karch Kiraly, '82, are the Lew Alcindor and Bill Walton of college volleyball.) During the half-hour meeting it was clear that nothing had escaped Scates's notice: not the angle of a player's arm-swing, not the position of fingers on the block, not the height of the toss on a jump serve.

Scates noted the preparations for the arrival of a visiting team two days later: "Do all the usual things -- deflate the balls and raise the net four inches." He has a deep laugh that seems to emanate from his toes, and by the time he gets it out he appears to be gasping for breath. After recovering from his own joke, Scates adjourned the meeting at close to 10 p.m. Later he ended the night with a celebratory glass of the Brazilian spirit cachaça, a new postmatch tradition that is his one acknowledgment that the end is near.

*****

Scates came to volleyball, and coaching, mostly by accident. Growing up in Los Angeles, he did not plan to go to college, which made his high school romance with Sue Zetterstrom highly unlikely. "She was a soc, active in the student government," he says. "The guys in her group were very preppy in their white bucks. I was in the car club, wearing dirty Levi's and a greasy duck tail." Scates's father was a dispatcher for Douglas Aircraft, and after graduating from high school, Al spent a summer driving a tractor at the plant. He was so miserable he resolved to find a different kind of job. He matriculated at Santa Monica College and lucked into a position with the parks and recreation department in Culver City, coaching baseball, basketball and flag football. "I loved it right away, and to my surprise I was pretty good at it," he says. His passion intensified as his teams quickly won county championships.

Scates had been a standout jock. His dream was to play basketball for Wooden, even though he was a 6-foot-2 1/2 center. He switched to football at Santa Monica, playing tight end. Like a lot of Southern California kids he had goofed around with a volleyball on the beach, but he had never been part of an organized team. During his freshman year his football coach formed a volleyball squad and talked Scates into trying out. "He cut me after about five minutes," Scates says. After a spasm of laughter subsides, he adds, "I wasn't very good. But that motivated me to learn the game."

That education came at Santa Monica's State Beach, where the best players gathered on weekends for games of two-on-two. The most coveted court was near the parking lot; if you lost there it might be two hours before you got another chance. "One day this guy roars up in a convertible and hops out with an entourage of pretty girls in bikinis," says Scates. "Someone from the team I'm playing against steps off the court to let him have his spot. I couldn't believe that. The first serve this guy hits to me is a moon ball that goes so high I lose it in the sun. The ball falls at my feet for an ace. Then he hits this spinning jump serve that freezes me completely. Another ace. I'm like, Who the hell is this guy?" It was Gene Selznick, the self-styled King of the Beach. Scates picked up the game's nuances by observing and competing against Selznick and another member of beach royalty, Ron Von Hagen. "There was no instruction back then," he says. "The only way to learn was to watch the best players."

In 1959, Scates transferred to UCLA to play volleyball, practicing at night in the musty Men's Gym, where his teams still gather. By then he had married Sue, so he kept his day job coaching youth sports. After earning a degree in physical education in 1961, Scates began working toward a masters, which extended his eligibility. When the Bruins' coach, Dr. Glen Egstrom, resigned in the fall of '62 he recommended that his observant outside hitter take over as player-coach. Scates went before athletic director J.D. Morgan to apply. "I introduced myself and explained how much I wanted the job, and he barely looked up," says Scates. "Finally I said I couldn't accept any money because I wanted to try out for the Olympics in 1964. At that point ol' J.D. jumped out of his chair and started pumping my arm and said, 'Congratulations, son, you're hired!' " Scates got a $100 stipend for equipment; that ran out before he had purchased uniforms, so he borrowed old basketball jerseys from Wooden.

Back then volleyball was not sanctioned by the NCAA, so Scates led his first team to the final of the U.S. Volleyball Association tournament. In 1963, frustrated by the difficulty of scheduling matches, Scates founded the sport's first collegiate conference, the Southern California Volleyball Association, installing himself as commissioner and beginning a decadelong run as benevolent dictator. (The SCVA would morph into today's Mountain Pacific Sports Federation.)

Scates' playing days for the Bruins ended in '63, but he kept working at the game and was named an alternate for the 1964 Olympics, the first Games to include volleyball. He didn't get called up for the trip to Tokyo, but in '65 he captained the U.S. team while at the same time coaching UCLA to its first USVBA championship. In the summer of '65, while in Mexico City representing the U.S., he caught wind that a few months later the Japanese men's and women's teams (the latter had won gold at the '64 Games) were scheduled to have a layover of several days in L.A. on their way home from a tournament in Brazil. Scates talked Morgan into allowing the first-ever volleyball matches in Pauley Pavilion, a triple-header featuring UCLA versus USC and the U.S. men's and women's teams taking on Japan. Scates then spent months promoting the event. "I drove from Hermosa Beach to Malibu nailing posters to telephone polls," he says. "I'd write stories longhand for the Herald-Examiner -- Sue would type them up and then I'd hand-deliver them to Bud Furrillo, the sports editor."

On Dec. 17, 1965, Scates coached UCLA to a resounding win over the Trojans then suited up for the U.S., which defeated Japan for the first time. But the real victory was at the gate. "Back then the biggest crowd I'd ever heard of for a volleyball match was a couple of hundred people," says Scates. "We brought in 5,000 -- paid. Afterward J.D. Morgan found me on the floor and said, 'I will personally see to it that volleyball is made an NCAA sport.' Luckily he had that kind of power."

While Morgan was working behind the scenes, Scates was reinventing the game. UCLA had won another USVBA title in 1967, and by then as many as 100 undergrads were trying out for Scates's team. In '68 he uncovered Toshi Toyoda, who was only 5-6 but had wizardly setting skills. "In those, all anybody did was high, slow, predictable sets to the outside," Scates says. "Toshi allowed us to do some new things." UCLA began running quick sets to its inside hitters and sophisticated combination sets in which two hitters were sent to the same area, overwhelming the one opposing blocker. "The guys we were playing against were awestruck," says Ed Machado, a Bruins setter from '68 to '71. "Our system was light years ahead of what any other team was running."

In 1970, Morgan finally came through on his promise, and volleyball was given the NCAA stamp of approval. With Toyoda serving as a graduate assistant and mentor to Machado, the Bruins went 24-1 and took the national championship. Scates would win four more rings in the next five years. He had simultaneously birthed an NCAA sport and its first dynasty.

*****

In 1975 Wooden retired from coaching, and he eventually settled in an office next door to Scates's. They talked almost every day, often about baseball, a shared passion. Scates was privy to Wooden's mischievous sense of humor: "He loved to leave me messages pretending to be a disgruntled alumnus. He'd say, 'It was nice to finally see the team play up to its potential at the end of the year -- how do you explain the poor results in the first half?' Then he would laugh and hang up. He'd always ask me later in the day, 'Did you get my message?' The really funny thing is that we would have just gone like 32-2 and won another championship."

Wooden generously shared his coaching philosophy; he once gave a special lecture to one of Scates's middle school physical education classes. In the early '70s Scates began giving back to his game, conducting clinics for auditoriums full of high school coaches from Medford, Ore., to Madison, Wis., to Mobile, Ala. In '78 the coaching clinics were folded into a larger operation called the Al Scates Summer Camp, an annual barnstorming tour that hit Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Ohio, New York and Southern California. Scates trucked in his own nets and balls, along with three or four dozen instructors, usually his current or recently graduated players. "Generations of players all over the country learned the game because of Al," says Harasymowycz, who attended his first camp as a 12-year-old in Buffalo. "Coach singlehandedly turned Buffalo into a volleyball town. Now it's a recruiting hot spot."

Scates advocated for the sport in other ways. NCAA volleyball's first three Final Fours came by way of at-large bids, and all the teams were from Southern California. "That was good for us," Scates says, "but it made it impossible to grow the sport." In 1972, as chair of the NCAA volleyball committee, he reorganized the Final Four so one team would automatically qualify out of the Midwest and one from the East, a system that endures. This has led to the rise of powerful programs such Penn State and Ohio State, which have taken rings off of Scates' fingers.

He has also had a profound effect on U.S. Olympic volleyball despite personal disappointment. (A two-time alternate who never got a call-up, he coached the 1972 national team but failed to make it to Munich when the U.S. lost a qualifier to Poland 15-13 in the fifth set.) In '72, Scates pushed through an NCAA volleyball bylaw to ensure that the college rules mirrored Olympics', to better prepare future national-team members. "Al instilled in us the dream that we could take the national team to new heights," says Kiraly, who led the U.S.' 1984 and '88 gold medal winners. Four other Bruins were key contributors on those teams. Fred Sturm ('76) coached the U.S. team to a bronze medal in 1992, and four years later Kiraly won gold in beach volleyball.

"Al's fingerprints are on a lot of Olympic medals," says Kiraly, who also led the U.S. to the '86 world championship. "From the grassroots to the college game to the international level, the impact he has had over five decades is mind-boggling."

Scates has coached 52 first-team All-Americas and seven players of the year, but the stat he seems most proud of is that four of his former players have won national championships as coaches. (Two others lost the title game.) Two dozen Scates disciples are coaching at the high school, club, college or national level, spreading the UCLA way. Of course, the UCLA way means something different to each of them.

"I believe the secret to his success is the competitiveness he builds into every practice," says Reed Sunahara ('86), who recently stepped down after 12 seasons as Cincinnati's coach.

As a boy Scates earned a quarter from his father for prevailing in a fistfight against the neighborhood bully, and he cultivates bare-knuckle toughness. The Men's Gym is bisected by a blue curtain that stretches from floor to ceiling. On one side are the first- and second-team players in a daily scrap for survival. "Al has a long history of benching All-Americas if they're getting outplayed in practice," says Sunahara. On the other side is what is derisively called the Bronze Medal Court, with 18 or so players desperate to get noticed. Scates rarely ventures over there, leaving it to his assistants to monitor the progress of the understudies. "The only way to move up to the first court is for a player to dominate every drill," says Harasymowycz. "The intensity and level of competition over there is absolutely ferocious."

John Speraw was a longtime UCLA assistant and has won two national titles in the past four seasons coaching UC Irvine, which used to be a perennial doormat. He believes Scates' defining trait is his preparation, which is built on the analysis of sophisticated statistics, many of which he invented. In the hours before a match Scates likes to be left alone to pore over the matchups, and he is constantly tweaking his lineup in search of the slightest edge. "The game plans are precise, the practices are efficient, the evaluation of talent is always spot-on," says Speraw. "Al's got that laugh and he's a fun-loving character, but beneath all that he is an obsessive preparer."

Kiraly, an assistant coach for the U.S. women's team, identifies yet another reason for Scates' success: "He's the best there's ever been as a tactician and with game management." This rep dates to at least the 1974 national championship game, when an undersized UCLA team took on powerhouse UC Santa Barbara. The Bruins were getting creamed in the fifth set when Scates summoned little-used Sabin Perkins to serve, despite a broken finger. He nailed three aces in a run of six straight points, and Scates stole another ring.

Bruins of more recent vintage like to replay the '98 national title game, against Penn State, in which UCLA again trailed in the fifth set. Scates benched Ben Moselle, a fifth-year senior and returning All-America, in favor of true freshman Mark Williams, who had not played a minute in the match. Williams led the comeback victory. "I've been a head coach for 10 years now, and I still don't have the courage to make a move like that," says Speraw. "But Al has always been utterly fearless."

For all the knowledge and attitude that Scates brings to the gym, many of his former players credit UCLA's success to a clanlike cohesion that Scates creates. Kiraly talks of a "brotherhood," saying, "We believed in each other absolutely, because Al believed in us." When Greg Giovanazzi ('78) died on March 19 after a seizure, Scates called numerous Bruins to give them the sad news and share stories about a colorful character. Days later Scates' voice was still thick with emotion as he discussed his former player and assistant coach.

Scates is also there in happier times. He always tries to make a former player's wedding. "He knows the wives, he knows the kids, he knows how your business is doing," says Machado. "If you're coaching he knows the score of your last match. Al simply loves being the patriarch."

A family vibe has been palpable at home matches this year. Rofer's nine-year-old son, Remington, sits on the bench, just as Scates's son, David, and daughters, Tracy and Leslie, did in years past. This season there have often been four generations of Scates's family at the matches, with some combination of his kids and four grandchildren joining his spunky 93-year-old mom. But Scates is trying not to get caught up in the sentiment surrounding his impending retirement. He's a six-time coach of the year and a member of a handful of Halls of Fame, but he says, "This year I'm working harder than I ever have on a team, because I don't get another shot."

Postseason play begins on Saturday, and in a delicious twist, this year's Final Four is hosted by a hated crosstown rival, which in an e-mail Scates refers to as U$C. "We all understand what the ultimate goal is," says Sealy. "It's just that for so long, UCLA volleyball has made the extraordinary seem routine, and maybe none of us appreciated the accomplishments enough at the time. I hope that no matter what happens, Al can take time to reflect and savor all that he has done."

Scates smiles indulgently at such talk. "That's all very nice," he says, "but I want another ring." This one he promises not to give away.

Senior Writer, Sports Illustrated Alan Shipnuck wrote his first cover story for Sports Illustrated as a 21-year-old intern in 1994. Like his cover subject, Ken Griffey Jr., Shipnuck matured into one of the best of his profession. When he was hired in 1996, he became the youngest staff writer staff writer in SI's history. Now a senior writer at the magazine, he writes regularly on golf and has been honored multiple times by the Golf Writers Association of America. In 2008 he became the first writer to finish first in the same year in both the feature and news writing categories in the Golf Writers Association of America annual writing contest. Though he specializes in golf for SI and Golf.com, Shipnuck has written on a variety of topics, including the 2007 (Brett Favre) and 2008 Sportsman of the Year (Michael Phelps). He currently writes a popular weekly column, Heroes and Zeroes, for Golf.com. His first book, Bud, Sweat & Tees, was published in 2001 and followed misadventures of unknown PGA Tour rookie Rich Beem and his caddie, Steve Duplantis. The book became a best seller after Beem's stunning victory at the 2002 PGA Championship. He is also the author ofThe Battle for Augusta National: Hootie, Martha, and the Masters of the Universe, which was published to excellent reviews in 2004; Publishers Weekly said Shipnuck "superbly recounts all of the debacle's hilarious, sad, serious and absurd details." His most recent book is The Swinger, a raucous novel written with fellow senior writer Michael Bamberger and released in July 2011. Shipnuck has also been a contributor to Artworks Magazine, Travel & Leisure Golf, Golf & Travel and Golf for Women and has appeared on CNN, NBC'sTODAYand ESPN's SportsCentury series, in addition to numerous other television and radio shows. A 1996 graduate of UCLA, Shipnuck lives in Carmel, Calif., with his family.