'Overwhelming evidence' shared with reporters in Saints case

• The testimony from disgraced defensive coordinator Gregg Williams to the league, in which he said he knew the program "was rolling the dice with player safety and someone could have been maimed."

• The charge, from what the league said was a handwritten note from a Saints defensive coach, that the defense pledged $35,000 for a defender to knock Brett Favre out of the January 2010 NFC Championship Game -- including a $5,000 pledge to the kitty from current Saints interim coach Joe Vitt. (Vitt denies the charge.)

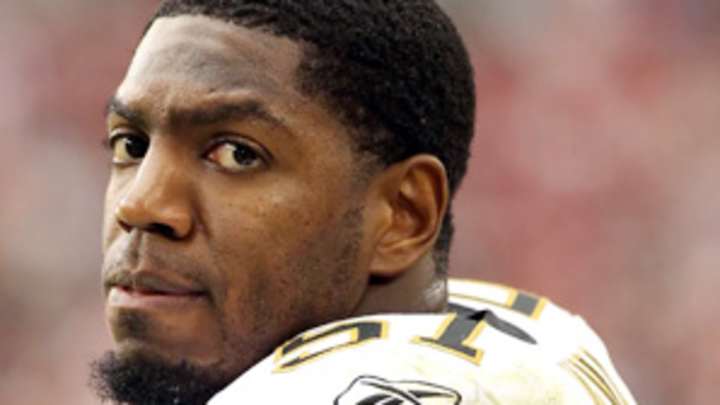

• The three sources the NFL claims to have who told league investigators linebacker Jonathan Vilma spurred the bounty on Favre by offering $10,000 himself during a night-before-the-game motivational speech by, as one of the sources said, "raising his hands, each of which held stacks of bills, that he had two 'five-stacks,''' to give to the player who knocked Favre from the game.

• The NFL Films-recorded quote from defensive lineman Anthony Hargrove, as first reported by SI in March, with Hargrove saying to defensive teammate Bobby McCray, "Give me my money,'' after Vitt told the team that Favre was out of the game with a leg injury. (Favre did return to the game without missing a play, but that wasn't apparent when Hargrove made his declaration to McCray.)

• The PowerPoint slide collected from a sweep of the Saints' computer system, from the night before the Saints' playoff loss at Seattle in January 2011, complete with a picture of TV bounty hunter Duane "Dog'' Chapman, that said, "Now is the time to do our job ... collect bounty $$$! No apologies! Let's go hunting!''

• The unending stream of evidence from Saints computers, which is going to create some very strange bedfellows inside the Saints' football facility ... seeing that the two-year sweep of all Saints' e-mails and computer-generated PowerPoints was OK'd by owner Tom Benson, who helped seal the case against the four suspended players and three coaches and general manager Mickey Loomis by allowing forensics experts to search for incriminating electronic evidence against his employees.

• The ledger sheet from an October 2009 game that showed safety Roman Harper due $1,000 for a "cart-off'' of Giants running back Brandon Jacobs in the second quarter, forcing Jacobs to leave the field for several plays.

"Overwhelming evidence,'' White called what the league showed reporters in a 75-minute presentation.

Specious evidence, the attorney for Vilma said in the morning, when lawyer Peter Ginsberg and Vilma walked out of the proceedings. "There is no evidence, because there was no bounty system,'' he said.

Vilma, in a statement to reporters outside the league's midtown Manhattan offices on Park Avenue, said NFL commissioner Roger Goodell in three months had destroyed the reputation he'd worked for eight years in the NFL to build. And Vilma criticized the process, in which the man who handed down the Saints' suspensions, Goodell, was also the one hearing the appeals. "I don't know how you have a fair process when you're a judge, jury and executioner,'' he said.

Summing up the day: The four players -- Vilma, linebacker Scott Fujita (now with Cleveland), defensive end Will Smith and Hargrove (now with Green Bay) -- due to have their appeals heard at NFL headquarters left in the morning because of a procedural issue. They felt they hadn't had the 72 hours the Collective Bargaining Agreement mandated to examine the evidence in the case, and the NFL offered to adjourn the case until the afternoon, by which time the 72-hour window would be valid. Vilma and Ginsberg chose to leave and not return, protesting the forum. Fujita, Smith and Hargrove returned for the afternoon session, just long enough to hear White's case against them. Then they left, apparently because they considered the probe unfair.

To be fair to the players, there was far, far more evidence of the pay-for-performance claims than the bounty claims. In fact, the Harper claim was the only one the league showed that resulted in a payout to a player for knocking a player out of a game.

However, the NFL has maintained all along that all it needs is evidence that a bounty program was in place and that money was offered to try to take opponents out of the game -- not that players were actually taken out of the game.

(The NFL said what the reporters heard from security chief Jeff Miller, legal counsel Jeff Pash and White was the same as the three players, not including Vilma, heard from the three NFL representatives earlier in the afternoon.)

Pash said the league wouldn't rule on the appeals immediately -- a full year suspension for Vilma, eight games for Hargrove, four for Smith and three for Fujita. He said Goodell will keep the case open for the remainder of the week in the hope that the players will make statements in their defense before he renders his decision.

Fujita was emotional as he spoke on a public plaza outside league offices. "I have yet to see anything that implicates me in some pay-to-injure scheme, not in the last three months, not in the last three days, not today,'' Fujita said, a couple of times pausing to compose himself. "And perhaps that's because there is nothing that can implicate me in some pay-to-injure scheme.''

In fact, there was no evidence presented to reporters that showed Fujita directly contributed money to a pool for distribution to players who hurt someone. Fujita told SI in March that he did contribute to the pay-for-performance system (for plays like interceptions and forced fumbles) but never to a pool for injurious hits. Apparently, when Goodell ruled, he took into account that Fujita was not the ringleader but, in the commissioner's mind, a major contributor to the program.

"Throughout this process,'' Fujita said, "it has become increasingly clear to me that just because someone disagrees with the NFL's interpretation of an incredibly flawed investigation it's assumed that he's lying and to me and that's a shame. I've played 10 years in this league and throughout my career I've done nothing but conduct myself in a positive manner. This has impacted my reputation, this has impacted my ability to provide for my family now and in the future and I have a hard time with that. The NFL has been careless and irresponsible and they have made mistakes. At some point they have to answer questions."

The league answered quite a few from reporters late in the afternoon in a conference room on the sixth floor of NFL headquarters. This was the first time since the story exploded on March 2 that the league opened up the investigation to reporters.

Miller said Benson "gave us his permission'' to examine the Saints' computer system to try to find evidence in the bounty case. White said there was a witness statement saying Vitt instructed Hargrove to lie about the existence of a pay-for-performance/bounty system if he was interviewed by NFL investigators after the game in which Favre was knocked around. Williams confirmed the story of Vitt asking Hargrove to lie. Vitt denied it. And league officials confirmed that players sometimes gave the money they'd earned from the program back, to increase the money in the kitty.

One of these times, the league claimed, Vilma gave the money back. In a 2009 game against Miami, Vilma, the league charged, earned $400 for two "whacks" -- explosive hits on an offensive players -- but had $200 subtracted for an "ME" (mental error). The league said Williams kept the money in a lock box in his office, and he'd distribute it the following week to players in envelopes. In this case, the envelope with the $200 profit to Vilma for the week was returned. "Gave back to kitty pool,'' the envelope containing the $200 read, according to the league.

There's little doubt the aggrieved players will find a way to take action against the league for the sanctions. But now that the league has shared its case with the press -- and, as a result, the public -- it's not quite the slam-dunk case of negligence the players have charged. Either way, this is a black eye that won't soon go away, and league officials seemed to take little joy in smearing such a charismatic franchise in a Manhattan boardroom at the start of a long, hot Monday.

"Does anyone think this is how we wanted to spend the offseason?'' Pash said, "taking one of the great stories of the NFL, the New Orleans Saints, where we're playing the Super Bowl this year, and having it dominate the headlines?''

No. But it is.