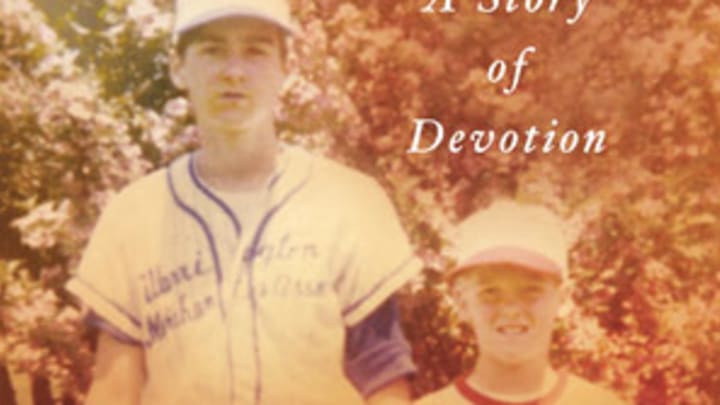

A former football star, high school sweethearts, a story of devotion

An adaptation from the book, "Like Any Normal Day: A Story Devotion." A true story.

Buddy was the star quarterback on his high school football team. Karen was an attractive Navy brat who had caught his eye his senior year. They were supposed to go out on their first date on an autumn evening in 1973 when fate intervened.

Buddy ... She would think of him every so often, and wonder how he was doing -- if he was even still alive. Years had passed since Karen Kollmeyer had seen or spoken to him, yet a bond had formed between them long ago. In the wake of a football injury that had rendered him a quadriplegic, he had promised that when he recovered -- not if, when -- he would walk back into her life and sweep her off her feet. But that did not happen. So she secured him in a special place in her heart, and there he remained until 1995, when a private investigator from Pennsylvania called her at the hospital where she worked as a nurse and told her: "Buddy Miley would like to speak with you."

Genially, the investigator said it was up to her, that if she preferred he would just inform Buddy he could not find her. But Karen was drawn in, even as she remembered a conversation she had had with Buddy 11 years before. By then resigned that he would not recover, Buddy had had asked her to move to Pennsylvania to be with him. She could not do it. No longer 17 and free of responsibility, she was divorced with a two-year old daughter to think of. Their parting had been heartbreaking. Karen had hoped that she could bring him some degree of comfort, but Buddy could not let go of the vision that they had created in high school: that one day they would be they would married. Karen gave the investigator her home number.

Buddy called the following evening. Married again and with two children, Karen would remember that it was a cheerful, what-have-you-been-up-to conversation that she was pleased to have. Buddy seemed to be in a good place. But in their ensuring conversations, which began running an hour or more, the strength she had heard in his voice began to waver. Fear had edged into it. For years, he had been cared for by his mother -- Saint Rosemarie, he called her. "Mom is falling apart," he told Karen. Incredibly, he asked if she would help set him up in an apartment if he came down to Alabama. When she rejected that plan, saying "How do you think that would even work?" he asked her in their very next conversation if she could help him contact Dr. Jack Kevorkian and arrange his suicide.

Stunned, Karen replied, "Does this have to do with me not wanting you to come down here to live?"

Buddy told her no, he had been thinking of ending his life for years. But Karen would always wonder.

Karen told me this story when I went down to Alabama to interview her in 2009 for the book I had just started researching, Like Any Normal Day: A Story of Devotion. In the 12 years that had then passed since Buddy had convinced his younger brother, Jimmy, to end his suffering and deliver him to Kevorkian -- an act of courageousness that would leave Jimmy as paralyzed psychologically as Buddy was physically -- Karen had carried with her the burden that perhaps she could have intervened by doing ... something. While the book explores an array of social issues, from the dangers of football to gray areas that enshroud the debate over enthunasia, it also steps away into an unusual love story, one that began in the innocence of youth and ended years later in unspeakable grief.

*****

Albert "Buddy" Miley was the star quarterback at William Tennent High in Warminster, Pa., when Karen became acquainted with him in the autumn of 1973. Both of them were seniors. He had long hair and a swagger he had borrowed from his idol, "Broadway" Joe Namath. Karen was not particularly fond of football, but they spotted each other one day in the cafeteria and an attraction developed between them. In the week before the third game of the season at Plymouth Whitemarsh, Buddy asked Karen if she would like to do something that Saturday evening. Buddy said he would give her a call. When Karen did not hear from him, she just assumed something came up, but soon learned that Monday in school that Buddy had fractured his vertebrae in the game and was paralyzed. Rumors circulated that he was near death.

Karen stopped by to see him at Sacred Heart Hospital. As the daughter of a Navy officer, she had moved from place to place during her youth, a circumstance that did not lend itself to forming lasting friendships. With some health problems herself, she had been treated at the Navy hospital, where she found herself surrounded by ailing Vietnam War troops. Seeing Buddy in the dreadful shape he was in reminded her of them. At the end of that initial visit, Buddy asked her to come back. And she did -- each day. Strapped upside down in a Stryker frame, a traction device that allowed him to be flipped over to prevent bed sores, Buddy would gaze down at her as she looked up at him from the floor. She would ask him, "Where do you want to go?" And in a soothing voice that would quell his intense pain better than any drug he would ever take, she would take him on a virtual trip to the beach, where they played in the surf and sat side by side in the sand as the sun dipped in the horizon. Buddy asked a nurse to bring her a yellow rose.

What Karen would remember is that they were so young. Neither fully grasped the permanence of what had happened to him. Instead, they spoke of the life they would share together. Karen told me, "Buddy had this elaborate plan. He would go to college to play ball, and I would go along as part of the package." But with the arrival of 1974, no sooner did Buddy come home from the hospital than Karen went in for kidney surgery. When Karen saw him again, he had become standoffish to her, as if he was searching for a way to let her go. But he could not bring himself to do it, and when they talked again and he discovered she would be leaving with her parents at the end of the school year, his eyes began to fill with tears. He told her not to contact him, that would be too hard, but when he could walk again he would find her. At graduation that spring, as both of them sat in wheelchairs on the stage, Buddy averted his eyes from her as she looked at him.

So the years passed. While Buddy remained at home with his parents in an addition the community chipped in to build, his bed by a window that looked out on a street that he had played in as a boy, Karen set out on a wayward journey into adulthood. On the heels of a stormy affair with an older man in Florida, she escaped into a marriage and headed off to Michigan. She had a daughter and then settled back in Florida when her marriage ended. One day in 1982, she picked up phone and found Buddy on the other end of the line. Someone had told him that she was single again, or soon to be. Karen was delighted to hear how upbeat Buddy sounded. He told her in the course of their long conversation, "I think of you every day." Perhaps because of the calming effect her voice had on him -- and I can think of no other explanation -- Buddy attempted to record that conversation. But he only captured one side: his.

Karen flew up from Florida with her daughter for two 10-day visits in 1984. When a friend drove Buddy to the Philadelphia airport to meet her on that initial visit, Karen lowered the visor above her passenger seat, and a yellow rose dropped into her lap. Over the course of those two visits, they reconnected to the tenderness they once shared. Magically, they stepped back in the cozy bubble that they had occupied in high school, that place that existed beyond the suffering that had claimed his dreams. Given her own travails, Karen looked upon Buddy as a safe harbor, someone who seemed to be able to peer into her heart with unobstructed clarity. In the course of their conversations, they ventured again into a virtual reality, as Buddy told her how it would be if they were husband and wife. Karen would remember that he had every detail in place: who they would invite to dinner parties, what they would wear, how she would fix her hair.

Karen told him it was never that way when you live with someone. "You have bad days," she said. "People get grouchy with one another."

Buddy promised her that would never happen. With sincerity in his eyes, he told her: "No one would treat you the way I would."

How hard it had been for her to step away from him. Karen told me, "I hoped and I believed that if he could have had a truly loving friendship with me, I could have been good for him ... The problem was that he could see me as nothing short of his wife." Karen found an apartment with her daughter by the Gulf of Mexico. She graduated from nursing school and remarried. Her second husband, Ron, was a respiratory therapist. They had a son. Within a few years, they moved from Florida to Alabama, where Ron took a better-paying job selling medical equipment. Karen became a nurse in the cardiac intensive care unit at a hospital in Birmingham, where she found herself holding the hands of patients in their final hours. When Buddy called her there in 1995, she hoped to do just that for her old friend ... hold his hand. And let him have a piece of her heart.

What followed would be an agonizing period, ever tilting from reality into the fantasy that had formed between the two of them over the years. In the conversations that ensued, Karen ceased to become a woman with a husband, two children and a job and instead become a projection of what he would have had were it not for that one split second of horror so long ago on a high school football field. Increasingly, Buddy would become playful and cross the line of propriety. He had come to think of Karen as his wife, and he would describe the day they had together. Karen let him do it. How could she not, with the end so near? While Ron did not know Buddy, he understood that Karen was "probably his last good memory." So he was supportive when Karen told him in the spring of 1996 she would like to fly up to Pennsylvania to say goodbye to Buddy. But he became somewhat agitated when Karen told him there would be another trip in July so she could join Buddy at a wedding reception he wanted to attend. Buddy told her it would be the prom they had not had a chance to attend.

*****

On the March day in 1997 that Buddy flew to Michigan with his brother Jimmy for their rendezvous with Kevorkian at a Quality Inn, Karen stood vigil by herself in Alabama. Ron had gone off to work, and her two children were at school. She and Buddy had spoken the previous evening; he had told her, "Oh, God, Karen. Do you know how much I love you? How long I have loved you?" Karen eyed the clock on her wall: 9:30 a.m. -- or 10:30 a.m. in Pennsylvania. Karen wondered if they had left yet. As the day progressed, she became increasingly anxious. At one point, he said aloud, "I know nothing about life!" From her kitchen window, which looked out on a shimmering lake, she could see the sun had edged lower in the horizon. When the phone rang, she picked up and asked, "Buddy?

"It's me, Karen. I'm in Michigan. I'm at the hotel."

"Are you sure about this, Buddy? Do you want to go home?"

"Nothing could change my mind," he told her. "It would be a 100 times worse for me if I lived through today."

Karen sat on the floor. Tears slid down her cheeks.

"I'm so sorry," she said. "I'm sorry, Buddy."

"Remember, you'll never be alone," he told her. "I'll always take care of you. You'll be with me when I take my last breath. I love you."

Buddy ... it would always strike Karen as odd how few days they had actually spent together since they left high school. Over the course of 23 years, it could not have been more than 40. Karen told me, "Buddy gave me more power over him than any person should have." For years, she wondered if by stopping him from coming to Alabama that she had in some way allowed his assisted suicide to proceed. But she could never know that, only that Buddy was an adult, had a free will, and had endured enough. In the years that followed, Karen would overcome her own despair and move on. But the part of her that would always remain attached to him would wonder ... if only.