Message from Minnesota: Three dots and a dash

This story originally appeared in the Dec. 14, 1970 issue of Sports Illustrated.

Okay, fellows, said Coach Bud Grant to his Minnesota Vikings, our quarterback this week against Chicago will be Bob Lee. Bob Lee? The punter? No, that was last year. This year, after Joe Kapp went off to seek his fortune in Boston, Lee, a 17th-round draft choice from University of Pacific, became Gary Cuozzo's backup. Two weeks ago, when Cuozzo severely sprained an ankle against the Jets, Lee went in and threw four interceptions. The Vikings couldn't have cared less. With Kapp, Cuozzo, Lee or, if Grant so chose, with pudgy Fred Zamberletti, the trainer, at quarterback, they knew they could beat Chicago just as they had beaten almost everybody else -- with their crushing defense. And, of course, last Saturday in Bloomington, Minn. they did, 16-13.

Frozen by Viking weather and savaged by the Vikings' superb front four, Chicago managed only two field goals against the best defense in football but made the game typically Viking close by scoring on an 88-yard kickoff return by Cecil Turner. The win was Minnesota's 10th in 12 games and enabled it to become the first NFL team to clinch a division title. Lee matched Turner's run with a 33-yard scoring pass to John Henderson, and Fred Cox more than matched Chicago's field goals with kicks of 21, 23 and 10 yards. But enough about points.

The day of the game broke clear and cruelly cold, with a wind gusting up to 40 mph turning 9 ° weather into a 33 °-below chill factor and the lawn at Metropolitan Stadium into solid green concrete. The Bears came out gloved and with giant heaters set up behind their bench. The Vikings came out bare-handed and heaterless. "We're out there to play football, not to keep warm," said Grant. "We'll be cold, but we'll survive. I want our players' full attention on the game every minute, not on keeping their backsides warm."

It's all part of the Grant master plan that in four years has turned the Vikings from a gang of violent individuals into a tightly disciplined football team. "Take our game with Green Bay last year," Grant said. "It's in the fourth quarter and it can go either way. Then their Donny Anderson gets hurt. They send in a substitute. Now he's got to be the warmest man on the field. He should have been, he was standing next to the heater all day. He comes in and pop! he fumbles, we recover and that was the ball game. And we didn't fumble once the whole game. As long as we live in this country, we must have the discipline of learning to play in it."

"If Grant says we'll win by freezing, then, by God, we'll freeze and win," said one Viking. "But I sure wish he'd tell my toes they weren't so cold." And so last Saturday the Vikings huddled on the sideline, huge men hunched over and stamping their feet for warmth, preparing to attack Chicago with their defense. Other coaches talk about getting good field position for their offense. Grant talks about good field position for his defense. "The defense wins, the offense sells tickets," he preaches. He took the role of quarterback and made it a bit part. "Kapp didn't win for us last year," he says. "He was just one-fortieth of the team. That's all Cuozzo is. That's all Lee is."

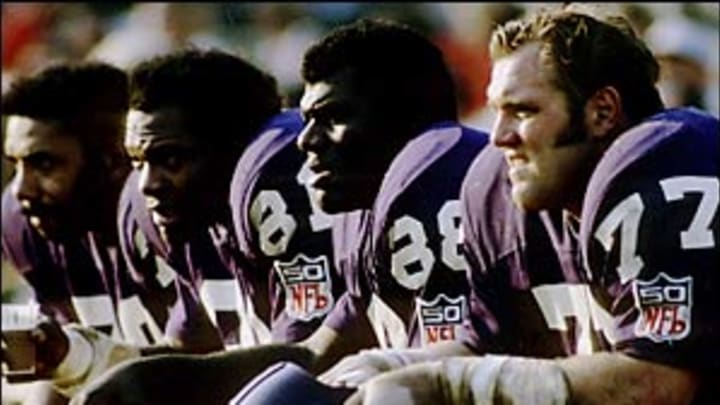

But then Grant has the front four, the Purple Gang or, as they sometimes call themselves, the Three Dots and a Dash, an allusion to the three blacks Jim Marshall, Alan Page and Carl Eller and the one white, Gary Larsen. Eller is the bachelor and free spirit; Larsen, the gentle family man; Marshall, the happy adventurer, making the most of every one of life's minutes; Page, at 25, the youngest, a little bit of each but in sum like none.

"Alan is still dealing in his potential self," says Eller, the 6'6" defensive end. "It would be hard right now to describe him, except to say he's truly a great person. Marshall is a guy who deals in the fantastic. Gary is a quiet person, a guy who enjoys being with his family, and he has a beautiful family. I think this makes him a beautiful person."

"Clothes are a passion with Carl," says Larsen. "Everybody kind of wonders what he's going to wear next. Last year he had a Cadillac limousine and he'd sit in the back and let a friend of his named Blue drive him around. Anybody else would have felt self-conscious, but not Carl. Then one day he just got tired of that and sold the car."

At a recent gathering, Eller appeared in a wolfskin coat, black leather bells and a cap of wolf heads. "That coat took a pack of wolves to make," says Page. "It decimated the wolf population of Canada. It's unbelievable but then so is Carl." Another recent Eller acquisition is a Charles Addams-type house which he shares with his mother. "Because I live with my mother, you know why I bought a big house," Eller says with a grin. "She has her privacy and I have mine. That house is my proudest possession. It represents a cornerstone of me. I think it's the only thing about me that is really solid."

Off season, Eller studies acting in Los Angeles at the Phillip Browning Workshop. "They teach realism in acting," he says, "the actual portrayal of a character as you see him. Ideally, I see myself playing a more sophisticated type of role. One where you would portray a more defined character. One with great definition. Something like a Lee Marvin or a Tony Quinn. The role I most identify with is Laurence Harvey in Butterfield 8."

Watching Eller swoop down on enemy quarterbacks, it is hard to equate him with Laurence Harvey or the aesthete who sat in a motel room last week and recited poetry, his own: 'What am I? Bird, tulip, grass or green? Whatever."

"I think the poet can be seen in the football player," says Eller. "Football is a great medium of expression, a performance that is more total because it is completely spontaneous. If you knew all about Carl Eller, then you could see Carl Eller in my playing, and from it you'd probably understand me even better."

The other poet of the front four is Marshall, who views life as a series of challenges and rushes forward to meet them all. At the moment his passion is skydiving. Before that there was fencing, skiing, water skiing, scuba diving, hunting, fishing, archery and....

"And oil painting, and licenses in real estate and as a stockbroker, and nine million other things," says Anita Marshall, his beautiful wife. "Nothing he does surprises me anymore."

But sky-diving? A professional athlete?

"Hey, it's 10 times safer than football," says Marshall, who has jumped out of a plane 200 times. "I just woke up at 7 one morning and decided I wanted to try it." At 9 he was at an airfield. At 10 he was at 2,800 feet and stepping out of a plane. "And it was great," he says. "For the first time I felt completely free, completely detached from earth. It was a feeling I've never been able to recapture."

"Now he wants to climb a mountain," says Anita.

"I've got one all picked out. It's in British Columbia. We got to within 60 miles of it last year, but that was as close as we could gel. I've got to climb that mountain."

"We climbed one," says Anita.

"Aw, that wasn't a mountain," Marshall says. "Besides, you were with me and you made me stop halfway up."

Most of Marshall's poetry was written for Anita. Like: "I love your lips while they are red with wine, and red with the wildest desire...."

"Oh, he had some real heavy lines," says Anita.

Marshall smiles at her. "They worked, didn't they?"

Marshall learned to ski the same way he learned to sky-dive. Eller took him to the top of the highest hill he could find and said, "Jim, follow me." And Eller took off with Marshall a few seconds behind.

"Carl thought it was funny," Marshall recalls. "He was laughing and yelling all the way down until he fell and I went past him. Then I stopped with one of those great swooshing slides. Swoosh! I damn near made it, too."

"Carl and Jim, I don't think I've ever seen them in a bad mood," Gary Larsen says. "They're always laughing, having a good time."

"They're out of their minds," says Page, trying not to smile. "When I first met Jim I thought he was stone crazy. Now that I know him a lot better...."

It was Marshall who led the rookie party in 1967, Page's first year. The veterans ordered the rooks to drink beer. Page said no, he didn't smoke or drink. Okay, they said, then you have to drink hot Coke or get out. Page got up and walked out.

"I have to admit I was kind of worried," he says. "I had heard all the stories about how the veterans treat the rookies, and at the time I thought a lot of those guys were crazy. I didn't know what they'd do, but except for some needling, they didn't do anything. The Vikings don't ride rookies. About all they have to do is sing for their dinner at training camp. And every day during the season they have to buy five dozen doughnuts and bring them to the locker room."

When the doughnuts arrive, it's every man for himself. If you get there first, you get all you can grab. If you get there last, there won't be anything but empty sacks.

"The idea is to sneak up on them without telling anybody," says Marshall. "But if you see other people getting in ahead of you, you yell 'Doughnuts!' and then everybody dives for them and you've still got a chance. There's more injuries going after the doughnuts than there is playing."

"Then Marshall goes around stealing everybody's doughnuts," says Page.

"I do not," says Marshall. "Besides, didn't I bring you a doughnut the other day? A cherry one?"

"Yeah, but you took a big bite out of it first."

"I did not. And what about the doughnut you stole from me?"

"I didn't steal your doughnut," says Page. "I stole Eller's. Right from where he hid it."

"They're all nuts over those doughnuts," says Clint Jones, the All-America running back from

Michigan State. "One day it was my turn to buy them and they all yelled at me. They said they were a week old and they threw them at me. I was embarrassed. Then out on the field they kept taking cheap shots at me."

"And you brought them in some old greasy bag," says Page.

"And they were a week old," says Marshall.

"They were only a day old," says Jones. "Everybody in Cleveland buys day-old doughnuts."

If the idea of great, muscular grown men fighting over doughnuts sounds silly, it isn't. It's part of the team's unique group therapy. Down deep in every Viking is the soul of a Don Rickles. Make a mistake and not only the coaches but 39 players will let you know about it loudly and colorfully. There is even a weekly Rock Award to the injured player who misses the most practices.

"It gets you healed in a hurry," says Larsen. "Everybody rides you, so you don't waste any time getting better. Make a bad play and wow! In a game against Washington I fell for a few sucker plays. A couple of days later the team gave me a giant candy sucker with a sign telling me to shape up or I'd be replaced by a button. As a result of all the ribbing, there are no hidden resentments on the team. We keep everything, and I mean everything, right out in the open. People come here and they can't believe how close we all are. We're all good friends. There are no cliques, no black and white. After every game there's a party somewhere and everybody goes. And if you can't make it you had better have a good excuse. Laughter eases an awful lot of tensions."

Of the four defensive linemen, Larsen is the toughest against the run. Because he is the slowest, he usually hangs back to check against the draw before joining the pass rush. "Gary is the most reserved of us, the quiet one," says Marshall. "A very enjoyable and genuine person. If I was ever going somewhere, and I was a little worried about my safety, Gary is the kind of person I'd like to have with me."

For Larsen, there is his football and there is his family. Everything he does, his wife Wende and their four daughters do. And usually whatever they do, they do outdoors.

"The two oldest girls, Robin [9] and Debbie [7], are even playing football," says Larsen with some amazement. "Tackle. The other day I heard Robin saying something about tackling this boy and I said, you mean touch, don't you? She said no, she meant tackle. They aren't coming home with any bloody noses, so they must be doing something right."

There is a fifth member of the front four, Paul Dickson, who fills in at tackle on occasion and is in his 12th season with the pros. He is a philosopher who suffered with the Vikings in their early years under Norm Van Brocklin.

"We went through some tough times," Dickson says. "Van Brocklin made us overly aggressive, and we were going in all different directions. Then Grant came in and did what Lombardi did at Green Bay he molded 40 people into a single unit. Now we're a wedge with all the collective force at one end pushing toward a single fine point. Success is only the willingness to do something longer, harder and better than anybody else. Success is no magical thing, just a lot of damn hard work. Norm demanded from us in an overt manner. Bud demands the same things, but he has allowed us to demand it of ourselves.

"This team is a unit of one, with no one individual greater than the team. Like the Sphinx said, 'A grain of sand is a desert and a desert is a grain of sand.' I didn't know what that meant until I saw Camelot. A little boy asked King Arthur if he could fight, and Arthur sent him away. As he watched the boy go, Arthur said, 'We are all drops of water, but some of them sparkle,' This team is 40 drops of water that sparkle."

When Grant came to Minnesota, he brought a great calmness and order to the Vikings. "What I had was timing," he says. "The team was ready to move. Coaching is overplayed. The graveyard is full of coaches. You can't win without players. Then we had a great draft to go with some experience, most of it on defense, which was good. Nobody wins without a defense."

The turning point was Alan Page. Until he arrived, the Vikings had good outside pressure but were weak at tackle. Page came as an end, a position he had played at Notre Dame, was quickly switched to tackle and went from mediocrity to greatness, and so did the Vikings.

"I didn't want to change," Page says, "but now it's the only place I want to play. I was restricted at end. Inside I can do more things, go in more directions."

"Eller is probably the premier pass rusher today," says Bob Hollway, the Vikings' defensive coach. "He has strength, quickness and great leverage. Marshall is probably the finest athlete on the defensive team. He has extraordinary balance and quickness. And Page is the most relentless player I've ever seen. He drains himself totally every game, and nobody gets off the ball quicker than he does. Larsen just kills you with that great strength."

"Look," say Page and Marshall and Larsen and Eller, "we're just four guys out of 11 playing defense. We don't do any more than the others. We've got fine linebackers and we've got a fine secondary. Everybody complements everybody else, and nobody does a greater job than anybody else."

Okay, you argue with them. Last Saturday the 11-man defense went out and turned Chicago upside down. In the first quarter the Bears had the ball three times and ran just nine plays for a net of nine yards. Chicago Quarterback Jack Concannon tried dropping back the normal seven yards, went to 10, to 12, to 14 and, at times, 20, and still he was desperately searching for an open receiver. When the game was over, the Bears had gained but 129 yards, 88 of them passing, and Concannon had thrown three interceptions. In the locker room, Page slumped in exhaustion on a stool and began to thaw. "Man," he said softly, "didn't that Bobby Lee play a great game out there today."