The Post-Pitta Problem (It’s a Big One)

To fully understand how the Ravens will be affected by losing tight end Dennis Pitta to a season-ending hip injury, you have to go back to the end of last season.

After a 31-28 overtime loss to the Redskins in Week 14, Ravens coach John Harbaugh made the tough decision to fire offensive coordinator Cam Cameron and replace him with quarterbacks coach Jim Caldwell. There were a lot of reasons why the Ravens went on to win the Super Bowl, including the fourth-and-29 screen pass to Ray Rice against the Chargers; Terrell Suggs returning from Achilles surgery; the offensive line becoming an immovable object once Bryant McKinnie was inserted at left tackle and Kelechi Osemele moved to left guard. But Harbaugh’s gamble with a new playcaller was vital.

The Ravens were 9-4 and headed toward a No. 1 seed through 14 weeks, but they were too inconsistent on offense. The passing game lacked rhythm and cohesion, but it wasn’t because of a lack of talent. Anquan Boldin was one of the strongest and most clutch receivers in the game. On the outside, Baltimore had two improving speedsters in Torrey Smith and Jacoby Jones. In the backfield, Rice and his backup, Bernard Pierce, were big-play threats on the ground and through the air. And quarterback Joe Flacco had arguably the best deep arm in the game—with an athletic tight end-duo in Ed Dickson and Dennis Pitta serving as a security blanket underneath.

So what was Cameron’s problem? His offense didn’t use all the threats in unison, or to their full potential. The Ravens had the pieces to attack all three levels to the defense—Rice, Pierce and fullback Vonta Leach in the short field; Boldin and Pitta in the middle; and Smith and Jones deep—but synergy never materialized because Cameron failed to use Boldin and Pitta in the best way possible.

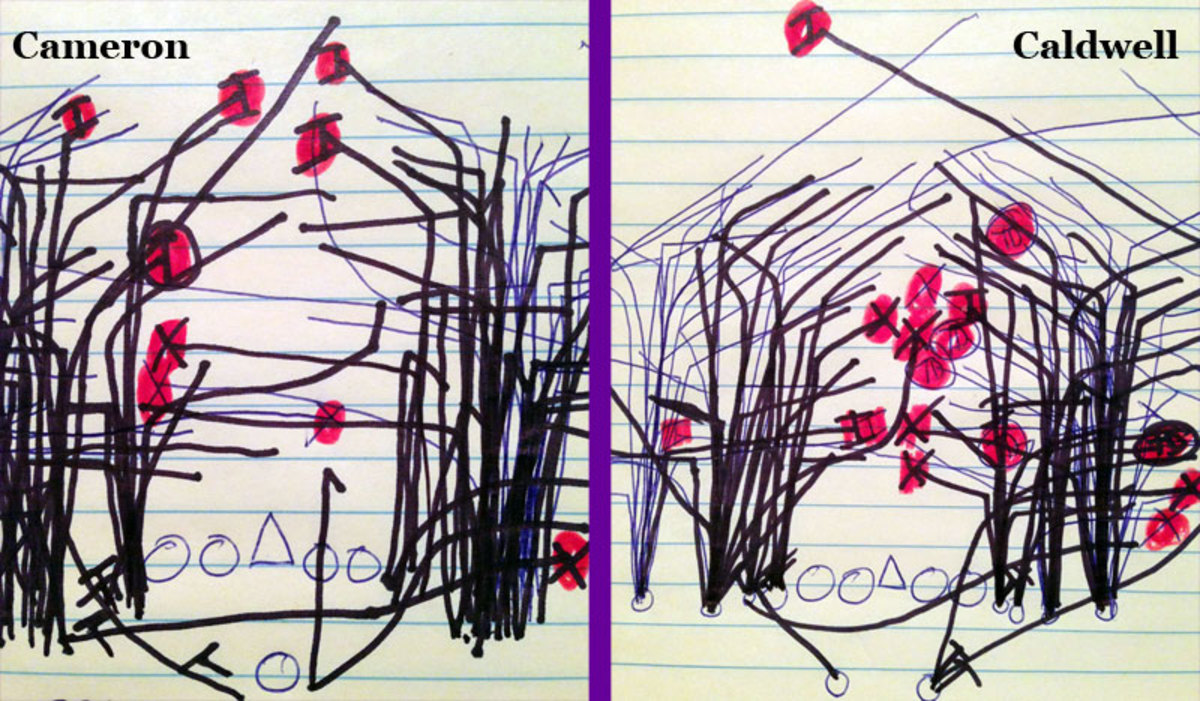

Here are a few illustrations from my notebook showing as much. (I must apologize: I’m no Picasso, but the takeaway will make Caldwell’s playbook seem like a work of art.)

The first picture shows routes run by Boldin (blue lines)and Pitta (black lines) in two games before Cameron got fired: Week 11 at the Steelers and Week 12 at the Chargers for Boldin; Week 7 at Houston and Week 12 for Pitta (he played just one snap because of a concussion against the Steelers, so I chose a different game to balance the sample size).

Notice how the vast majority of routes run by Boldin and Pitta were from the in-line tight end position to the sidelines, with just eight passes and three short receptions (for zero touchdowns) thrown to the middle of the field. Cameron, who is a disciple of the late Cardinals and Chargers coach Don Coryell, used them mostly on seam routes and toward the edges of the field, often of the short variety.

Now, let’s look at the routes Boldin and Pitta ran in the AFC Championship Game against the Patriots, and in the Super Bowl against the 49ers once Caldwell was firmly entrenched as the coordinator.

It’s almost the exact opposite approach. Most of their routes were run between the slot positions on either side of the ball. There were 12 passes thrown in the middle of the field, with nine completions (four touchdowns). Caldwell didn’t overhaul the offense—it’s impossible to change a system in the middle of the season, let alone the final few weeks—but this was a major tweak to the routes being run by Boldin and Pitta.

Look at all the in-breaking routes (especially deeper down the middle of the field) the Ravens used under Caldwell compared to Cameron. Even if the passes weren’t completed, these routes were complementary to the other offensive weapons. Threatening the mid- to deep-level of the field between the hashes with Boldin and Pitta put pressure on a defense. It made safeties stay closer to home, which opened up the outside for Smith and Jones, and/or it caused the linebackers to drop a little deeper, which helped give Rice, Pierce and Leach a little more room to make a play once they caught the ball. Under Caldwell, the Ravens used all of their weapons in unison, and it was a beautiful thing to watch.

Pitta against the Colts in the Ravens' 24-9 wild-card win. (David Bergman/SI)

WHAT NOW?

This offseason started with Boldin being traded to the 49ers because of his contract. I had studied Ravens film before sitting down with Smith for a recent story about his emergence in Baltimore’s passing game, and I kept coming back to the same thought: For the sake of Smith and Jones, the Ravens better find a competent replacement for Boldin.

One of the Ravens’ favorite ways to spring a big play last season was to put a safety in a bind by crossing Boldin and/or Pitta underneath him, while sending send Smith or Jones over the top. It’s a simple concept that all teams use, but the Ravens had all the pieces to make it work. If the safety chooses to cover the underneath route, the deep receiver should be one-on-one and looking for the end zone. If the safety stays deep to protect against the big play, Flacco should have an easy throw to the underneath crossing route.

It’s how Smith burned cornerback Champ Bailey early in the Ravens’ divisional playoff game against the Broncos, and it’s how Jones scored just before halftime in the Super Bowl. Each time, the safety cheated toward Boldin or Pitta.

Once Boldin left, the Ravens clearly thought Pitta could do a comparable job. He was poised to break out in his fourth season, and he certainly would have drawn coverage in the middle of the field. The Ravens would have continued with the same philosophy ... that is, until Pitta dislocated and fractured his right hip on July 27 while trying to catch a pass from Flacco.

Doubling Down on the Ground

It makes perfect sense for the Ravens to use running backs Ray Rice and Bernard Pierce at the same time in the post-Pitta/Boldin era. So why haven't they done it?

Peter King asked the champs about their backfield plans.

It was one thing to replace Boldin, but replacing

both

of the Ravens’ middle-depth threats is entirely different. Entering his fourth season, Dickson has made steady enough progress to take on a larger role, but he alone isn’t the answer.

The Ravens need two pass catchers who are capable of living in the middle of the field—the unforgiving ground that’s not for thinly built speedsters or for the faint of heart. It requires a rare breed who has the guts, the strength and the right feel for the game to excel in an area where defenders are looking to lay bodies out on the ground, or to jump short routes and turn them into a pick-six. That’s what made Boldin and Pitta so special last season, and what elevated the Ravens' offense to a championship level.

Dickson has many strengths, especially toughness, though he doesn’t have the same natural feel for route running and catching balls as Pitta. But let’s assume that Dickson makes the leap and proves himself equal to Pitta. Who is going to be the Ravens' other threat over the middle?

Visanthe Shiancoe has shown that ability at times in his career, but can he still do it at 33? The Patriots didn’t think so last season, and at the time they were trying to find a stopgap to fill in for tight ends Rob Gronkowski and Aaron Hernandez, their standout middle-of-the-field players. Do any of the Ravens’ young receivers possess the strength and intestinal fortitude to repeatedly catch passes down the middle of the field?

If not, the Ravens will have a hard time replicating one of the key factors that made them champs last season: they won’t have a passing attack that forces a defense to worry about the entire field.

It was one thing to part ways with Boldin. Losing Pitta just might put the Ravens back where they were under Cameron—a donut with good stuff on the outside, but nothing in the middle. Filling that hole was the secret ingredient that gave Baltimore its second world championship last season.

[si_video id="video_464C6019-178A-F7EA-9021-5427AF5C207F"]