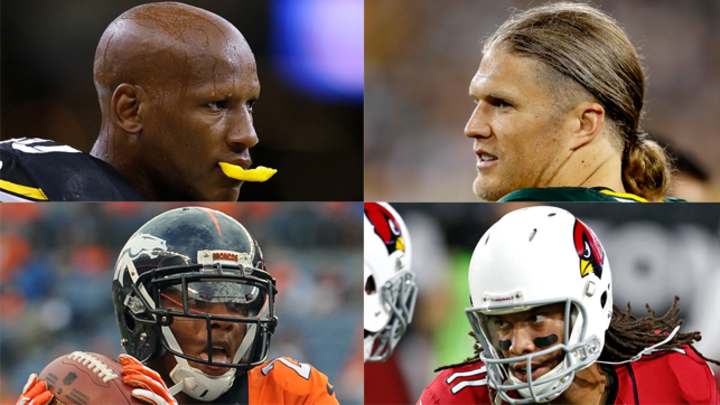

The 32 Pivotal Players for the 2016 Season

Introducing a new Friday column, All 32, in which The MMQB’s Andy Benoit weighs in on every NFL team. Content for this week’s piece, on each team’s pivotal player, appears in Sports Illustrated’s 2016 NFL Preview

Arizona: Larry Fitzgerald, WR

At 32, Fitzgerald has lost speed and quickness. But here’s what people forget: A receiver sets the pace; the cornerback must react to him. And so a wideout with polished mechanics, an understanding of spacing and coverages, plus a capacity for adjusting to and snagging balls in midair can thrive at almost any age. Indeed, Fitzgerald caught a career-high 109 passes last season, his 12th in the NFL. But Fitz’s contributions extend beyond numbers. Before coach Arians’s arrival in 2013, Fitzgerald was a pure outside receiver, often stationed on the weak side, where he’d have extra field to work with. Arians moved him to the Z receiver, aligning him closer to the formation or even in the slot, which meant he had to play a critical role in run blocking. That’s not an easy change for a longtime star wideout to embrace—but Fitzgerald has done that, not only by making more catches but also by becoming integral to the rushing attack as a blocker.

Atlanta: Desmond Trufant, CB

Second-year coach Dan Quinn wants to re‑create the type of defense he had in Seattle, where one of his core pieces was cornerback Richard Sherman. In Quinn’s system, the inside defenders play zone coverage while the outside corners often play press man. A premier press-man corner can essentially take away one side of the field; that, in turn, shrinks the space the inside defenders have to cover, allowing them to take more chances and swarm to the ball. Quinn is still trying to piece together his unit, but he already has his Sherman in the 25-year-old Trufant. The 2013 first-round pick from Washington is not brash like Sherman, so he doesn’t stand out. He also isn’t targeted as often, which is why he has only six career picks (just one in ’15). But a corner’s primary job is not to make plays; it’s to stop them. The 6-foot, 190-pound Trufant, with his short-area agility and feel for how receivers execute, is a true stopper.

Baltimore: Brandon Williams, DT

Meet the best football player you’ve probably never heard of. Williams is 6' 1", weighs 340 pounds and was drafted out of Missouri Southern (Division II) in the third round in 2013. He’s become a dominating force, but in a generally thankless role. That isn’t to say he can’t, and doesn’t, flash. Many think of the Ravens’ defense as a 3–4, which would make Williams a nosetackle, but in terms of gap responsibilities, it’s really more of a 4–3, and Williams is actually a nose shade, lining up over the center’s shoulder. His job is to plug the A-gap and take on the double teams that offenses like to dish inside. He still has the freedom to penetrate, though, and he often does. Maybe Williams will be more noticed after this year when he becomes a free agent; the bidding will make plain how formidable and valued he really is.

Buffalo: Stephon Gilmore, CB

It was news when Gilmore showed up to training camp. In the final year of his contract, he was expected to hold out for a long-term deal. Gilmore’s history of shoulder and wrist injuries makes it tough for GMs to assess his value, but when he’s on the field, there’s no doubt about his worth. With long arms, sturdy mechanics and short-area read-and-react ability, he’s a top-level corner. When Rex Ryan took over in Buffalo last year, he thought Gilmore would play the Darrelle Revis role in his blitz-happy defense. But with 2015 second-round pick Ronald Darby showing elite cover skills, the 6' 1", 190‑pound Gilmore didn’t need to shadow the top receiver. Instead he usually played the right side, Darby the left. For most teams, having two bona fide cover corners is a luxury. But in a scheme like Ryan’s, which relies on matchup coverages downfield, it is imperative. Without Gilmore, the Bills could not play their aggressive style of defense.

Carolina: Cam Newton, QB

For all his growth as a pocket passer, throwing the ball is not Newton’s most valuable skill. Running it is. It’s not just that Newton has a blend of speed and power never before seen at QB. It’s that defenses have to account for that combination on every down, while OC Mike Shula has done a masterly job designing plays to exploit it. Many of Carolina’s runs present a read-option look, forcing at least one defender to stand still and keep his eyes on Newton. But these plays don’t simply pose a handoff-or-no-handoff dilemma; variations of other running plays are built into them. The Panthers might feature a zone run on the front side for the tailback and a “power” run on the back side, in which a pulling lineman clears the way for Newton. The D has to account for entire play concepts moving in opposite directions. And it’s only possible because of Newton.

Chicago: Alshon Jeffery, WR

Fifth-year receiver Jeffery is 6' 3" and 218 pounds, with long arms, baseball-mitt-sized hands and a stride that covers about as much ground as the blast from a rotating sprinkler. His catching radius is equally huge. Though the Bears failed to sign him to a long-term deal—he’ll play 2016 under a $14.6 million franchise tag—Jeffery is more valuable to Chicago than he would be to any other team, especially with Jay Cutler at the helm. Last year Cutler played with discipline in the scheme installed by coordinator Adam Gase (and now run by Dowell Loggains). However, history suggests that the 33-year-old QB can turn back into a wild stallion at any moment. Cutler’s arm strength allows him to take chances, but inconsistent mechanics sometimes punish him when he does. A plus-sized receiver with Jeffery’s otherworldly leaping abilities and galactic catch radius can make those questionable throws look ingenious.

Cincinnati: Tyler Eifert, TE

Cincinnati’s offense really clicked last season. The scheme was the same, but everyone was more experienced playing together, and Eifert, a 2013 first-round pick, blossomed. After missing most of the ’14 season with a broken right elbow, the tight end emerged as a red zone weapon. He doesn’t have Julius Thomas’s length or Rob Gronkowski’s brawn, but the deceptively athletic Eifert hurt defenses running down the seams and on routes beginning from a wide-split position, where he was winning battles against some cornerbacks. He assumes an even more significant role in 2016, as quarterback Andy Dalton adjusts to new wide receivers Brandon LaFell and Tyler Boyd, a second-round pick from Pitt. Eifert is recovering from May surgery on his left ankle, and his return by September is in question. If he’s out, the Bengals’ schematic continuity and red zone flexibility will suffer.

Cleveland: Joe Thomas, T

Whenever a left tackle is drafted early in the first round, people love to say, “Here’s their 10-year starter.” But left tackles can go bust like players at any other position. Even if they don’t, having a rock-solid starter protecting the quarterback’s blind side does not solve every problem. Just ask the Browns. Thomas is now entering his 10th season. In 2007, after he was taken No. 3 out of Wisconsin, Cleveland went 10–6 and just missed the playoffs. Every year after that they have finished below .500. In all but one of those seasons they were 5–11 or worse. But don’t blame Thomas, 31. He’s one of the league’s steadiest blocking technicians. In pass protection he’s tremendous at moving his feet steadily and close to the ground—mowing the lawn, as it’s called. This is why he’s rarely off balance. And his football IQ is off the charts. The irony is that Thomas’s excellence makes him the best trade bait for rebuilding Cleveland.

Dallas: Travis Frederick, C

If the Cowboys are to regain their form of 2014, when their running backs averaged a league-best 142.9 yards per game, they’ll need 1) Tony Romo back healthy ASAP, calling run-play audibles at the line of scrimmage and 2) improved play from the most talented O-line in football. The group’s headliner is the spring-footed left tackle Tyron Smith. But the keystone is Frederick, the 25-year-old center. Dallas is primarily an outside zone running team, which requires the front five to stretch blocks toward the sideline and pin defenders back inside. The center’s job is the most difficult: Not only must he snap the ball before firing into his block, but opponents also align their largest D-linemen over his head or shoulder. Frederick is one of the NFL’s best at quickly getting around that defender. He’ll need to keep up that pace in ’16 to get the Dallas run game back on track.

Denver: Chris Harris Jr., CB

The Broncos’ strategy in the Super Bowl showed the sort of freedom that Harrisgives them. When the Panthers played three wide receivers, they did so expecting Denver to sub out a linebacker for a third corner. Instead, the Broncos subbed a safety, which kept their hybrid front seven intact and negated the advantage that Carolina hoped to create for its running game. This was huge, and it was only possible because Denver has three first-class corners who can cover one-on-one. The key CB is Harris, who shadows the quickest, and usually most versatile, wide receiver. Not only is he suffocating on the outside, but he’s also so comfortable inside that he’ll align at linebacker in the rare instances when his receiver goes into the backfield. Von Miller is the MVP up front, but Harris is the main man at the back end.

Detroit: DeAndre Levy, LB

In 2014 the Lions ranked first defending the run, and they finished 11–5. Last year their run defense fell to 19th, and their record to 7–9. Yes, some of that slide can be attributed to the free-agency departure of All-Pro defensive tackle Ndamukong Suh. But it was also due to a hip injury that sidelined Levy for nearly the whole season. When healthy, Levy is as keen as anyone in the league at identifying plays and picking angles to the ball. That’s important because it gives the Lions a run-stopping presence in their five-DB, two-LB nickel package. The plus side for a defense in the nickel: There’s more athleticism on the field, which helps in pass coverage. The downside: By subbing a corner for a linebacker, there’s less size in the box—and, often, one less body in the box—and that means more room to run. A ’backer with Levy’s range and instincts can offset this disadvantage.

Green Bay, Clay Matthews, LB

For the past year and a half Matthewshas been a good soldier and filled the perpetually iffy inside linebacker position in the Packers’ defense. There he faced more blocks, took on more coverage assignments and enjoyed less glamour than he would have rushing off the edge. In 2016 he returns to his natural outside spot. But if Green Bay strategizes wisely—and coordinator Dom Capers usually does—then on critical passing downs Matthews will see plenty of action back inside. One of the founding fathers of the venerated zone-blitz, Capers often rushes his linebackers right up the middle. That’s the shortest path to the quarterback—and if the pressure doesn’t get home, a blitzer can at least obstruct the QB’s line of vision. One of Capers’s favorite blitzes is Fire X, where two inside ’backers crisscross their blitzes to confuse and re-angle blockers. And Matthews is the most dangerous Fire X blitzer in football.

Houston: DeAndre Hopkins, WR

When the Saints visited Houston last November, they did something unusual: They often double-teamed Hopkins with their free safety. That left the middle of the field open and every other defender in one-on-one coverage. The strategy was not only a testament to Hopkins’s productivity—his 1,521 receiving yards in 2015 were third best in the NFL—but also a reflection of the Texans’ scarcity of other pass-catching threats. This is why Houston spent high draft picks this spring on two speedy receivers, Will Fuller and Braxton Miller. Their presence should benefit Hopkins. While he is great at tracking balls and making contested catches, he lacks great speed and is not always a reliable route runner. Receivers who can stretch and spread the field will create more operating room and more margin for error for the fourth-year pro as he learns the game’s nuances.

Indianapolis: Vontae Davis, CB

The idea of a blitz, if it doesn’t create a sack, is to force the quarterback to throw the ball early. When that happens, corners need to be up in receivers’ faces, or those quick passes will be easy completions. Coach Chuck Pagano, who excelled at manufacturing pressure through blitzes when he was a coordinator in Baltimore, hired former Ravens linebackers coach Ted Monachino during the off-season to serve as his DC in Indy. This should mean more blitzing, but only if Davis stays Davis is healthy. (He's currently out until at least October with an ankle injury.) It is hard to call the 5' 11", 207-pound Davis a true shutdown artist because he doesn’t travel with receivers when they motion into the slot, and he prefers to stay on the defense’s righthand side. But he’s very close to that status, and he will be essential to a pressure defense. Few corners are as physical and tight in their coverage as the eighth-year pro.

Jacksonville: Allen Robinson, WR

Last season the Jaguars had 72 pass plays of 20 yards or more, tying the Saints for the most in the NFL. The receiver on a league-leading 31 of those plays was Allen Robinson, who finished sixth in the NFL with 1,400 receiving yards and caught 14 touchdowns, tied for the league’s best. The 6' 3", 218‑pound Robinson, long in body and in stride, can snag balls that are away from his frame and eat up space with great build‑up speed late in routes. He’s a perfect fit for QB Blake Bortles, who has a lively arm but takes time to wind it up. To accommodate his slower release, the Jaguars have built their passing game around downfield play-action routes that take time to unfold—and allow Robinson time to get open. The beauty of play-action is that it’s almost always used on early downs, when defenses are in predictable coverages, giving the designs an even greater chance to succeed.

Kansas City, Derrick Johnson, LB

In 2015 inside linebacker Derrick Johnson quietly had one of the most remarkable seasons in the NFL, with 116 tackles, four sacks and two interceptions. At 33 and coming off a torn right Achilles suffered in Week 1 of 2014, Johnson showed no drop in the fluidity and swiftness that has long made him one of the game’s best all-around run defenders. As he’s aged, his football awareness has only grown. The Chiefs, like many teams seeking greater coverage versatility, prefer to play a “big dime” package featuring three cornerbacks, three safeties and one linebacker. The danger of doing so is that the undersized defense can be vulnerable to the run, even against an offense in a spread formation. Having a 6' 3", 242-pound ’backer with awareness and multidirectional movement skills like Johnson offsets much of that risk.

Los Angeles: Mark Barron, LB

One of pro football’s fastest-growing trends is the rise of three- and four-safety dime packages—replacing linebackers with box safeties. And there’s no greater beneficiary of this movement than the 6' 2", 213-pound Barron. The No. 7 pick in 2012 by the Buccaneers, Barron floundered for 21⁄2 years as a strong safety in a zone-based scheme before being traded to the Rams, who smartly recognized that he’s best on the attack, not reading and reacting. So they made him a linebacker who would blitz and chase ballcarriers behind a penetrating defensive line. Barron has flourished. Yes, there can be problems when a 310-pound run blocker gets his hands on him. But with the NFL presenting an increasingly space-oriented game, those sorts of matchups are more rare. Barron also provides flexibility with coverages because his experience at safety helps him to better guard tight ends.

Miami: Ndamukong Suh, DT

Suh’s first year as a Dolphin was tumultuous—there were reports that the former Lion was deviating from the scheme, Miami played poorly, and the coaching staff, including defensive coordinator Kevin Coyle, was fired last October. Now Suh has a chance at a fresh start with new DC Vance Joseph, who has promised a more attack-oriented approach—which means more blitzing on third down. But to do that the Dolphins need to get stops on first and second down, and that’s where the 6' 4", 305-pound Suh comes in. In Joseph’s 4–3, Suh will most likely often align on the same side as the tight end. Three blockers (the tight end, tackle and guard) will take on Suh and the defensive end, with Suh being the one who gets doubled. He’s seen plenty of this in his career, and his best attribute is the power he uses to wear down opponents late in the play. Miami’s system will be depending on it.

Minnesota: Adrian Peterson, RB

At 31, Peterson still has an unmatched ability to jump-cut laterally. But for all his greatness, Peterson is a remarkably limited runner stylistically. He doesn’t like rushing behind a lead blocker or out of the shotgun; those sets require that a ballcarrier wait for the action to unfold. He also doesn’t like to run outside by design; that, too, requires the patience to let blocks develop. Peterson’s aversions mean that Minnesota must eliminate several chapters from its playbook. Goodbye sweeps and stretch zone handoffs; hello, inside zone, “power” and “counter”—plays where blockers double-team in the trenches. From there, Peterson can take a handoff and immediately hit a hole. It’s predictable, but it doesn’t require highly athletic blockers, leaving the Vikings more flexibility to spend on D. All the while, their ground game remains dominant because Peterson is so obscenely effective, and he’ll have to be with Teddy Bridgewater gone for the year.

New England: Martellus Bennett, TE

Hear out my case for Bennett. He is one of the 10 best all-around tight ends in football, but this year he’ll be, unequivocally, the second-best one on his team. That doesn’t mean he can’t be almost as valuable as Rob Gronkowski. Bennett, 29, gives New England two tight ends who can run routes from anywhere as well as block in the run game. What makes the Patriots hard to defend is the way they use their tight ends to create mismatches for other players. New England is particularly clever in deploying them outside, which can result in a slot receiver being covered by a linebacker. With tight ends who can win their routes, such formations border on unstoppable. Even better: The Pats can run the ball with these same tight ends, allowing them to go from spread formations to condensed ones without substituting. With the addition of the 6' 6", 275‑pound Bennett defenses will struggle to match up.

New Orleans: Michael Thomas, WR

It’s possible that Thomas, the second-round pick out of Ohio State, will be a bust. But the role he’ll play in New Orleans gives him every chance to succeed. In the aggressive downfield designs that define coach Sean Payton’s system, Thomas will be the slot receiver. Most offenses these days use shifty, horizontal slot weapons—your Julian Edelmans, your Doug Baldwins. The Saints are different. They attack vertically and in the middle of the field, so they need a big-bodied wideout who can high-point the ball while running down the seam. Marques Colston, a seventh-round pick, became a perennial 1,000-yard receiver doing this. Thomas gets the first crack at being the new Colston. It can be an easy way to get rich because so few corners play inside, and even fewer have the size to match the 6' 3", 212-pound Thomas. The seam-route runner in New Orleans has a lot of advantages.

New York Giants: Odell Beckham Jr., WR

When your top receiver is the best in the world at tracking balls downfield and getting in and out of breaks, defenses are going to center their game plans around containing him. Just knowing this is an advantage to the Giants and their veteran QB, who excels at identifying mismatches and adjusting before the snap. First-year coach Ben McAdoo’s scheme uses three-WR formations regularly. When the offense spreads out, so does the defense, revealing where double teams are likely headed. Aligning Beckham’s wide often forces a safety to shade that way, leaving receivers one-on-one on the other side or down the middle. This is how average receivers can be made to look great. Big Blue won’t always keep Beckham wide, of course. They’ll also put him in the slot or backfield, forcing a linebacker to double-team him instead of a safety. The more ways they use him, the more pressure opposing defenses feel.

New York Jets, Darrelle Revis, CB

All-Pro cornerback Darrelle Revis hit some rough spots in 2015, with struggles against Raiders rookie Amari Cooper in Week 8, the Bills’ Sammy Watkins two weeks later and the Texans’ DeAndre Hopkins the following game. But Revis won plenty of battles too, taking on top receivers ranging from true slot Julian Edelman in New England to Jaguars perimeter weapon Allen Robinson. At 31, Revis might be a half-step slower, but his game has always been predicated on smarts and technique anyway. Which is why coach Todd Bowles builds his blitzes and coverages around Revis’s lockdown skills. He won’t be relied on this way every down; Bowles, while partial to man coverage, still calls plenty of zone. But on money downs—third-and-long or hurry-up situations—Bowles becomes aggressive with his pressures, and that’s where having a true No. 1 corner is crucial.

Oakland: Kelechi Osemele, G

When the Raiders shelled out $25.4 million guaranteed in free agency in March for Kelechi Osemele, many thought they would try to maximize their return on investment by moving him from left guard to the more valued position of left tackle. Late last season the injury-depleted Ravens actually had to play the 6' 5", 330-pound Osemele at that tackle spot, and he wasn’t bad. Still, Oakland smartly understood that it was better off keeping him inside, where he is utterly dominant. Osemele is phenomenal blocking on the move, and he gives the Raiders an interior offensive line that is second only to the Cowboys’ in mobility. Center Rodney Hudson is quick. Oakland’s other guard, Gabe Jackson, is not, but he moves efficiently at 335 pounds. Having three mobile blockers up the middle will be of great help to Latavius Murray, a running back who must have his rushing lanes clearly defined.

Philadelphia: Fletcher Cox, LB

In June, when the Eagles gave Fletcher Cox a six-year, $102.6 million extension ($63.3 million guaranteed), pundits gasped—but Cox is worth every penny. Aside from J.J. Watt, no pure D-lineman is more explosive in his initial step after disengaging a block. And like Watt, Cox (who has outstanding quickness off the snap and a hearty reserve of brute strength) is tremendous at disengaging from blocks. For his first four seasons Cox played on an Eagles D that used myriad looks up front and at times left him with the thankless job of simply trying to hold ground against two blockers. New coordinator Jim Schwartz is changing that with a true 4–3 scheme and fewer fronts, which will put the 6' 4", 310-pound Cox in all-out attack mode. The Eagles are good but not great at D-end. Normally that’s not enough. But it can be when you have a D-tackle like Cox, who consistently penetrates or demands extra attention.

Pittsburgh: Ryan Shazier, LB

The Steelers run an intricate zone scheme that demands their midfield defenders adjust their help coverages on the fly, disguise and execute complex blitzes, and, above all else, read and react in the run game. It takes veteran awareness and first-round talent to do this, which is why Pittsburgh’s model has been to draft linebackers early and defensive backs later—the opposite of how most teams do it. These linebackers need time to excel in the system, and the latest to blossom is 2014 first-round pick Ryan Shazier out of Ohio State. Last year injuries limited the 6' 1", 230-pound Shazier to only 12 games, but down the stretch he was the Steelers’ most dynamic defender. His straight-line speed is the best on the team. (Yes, the team; over the summer he beat wideouts Antonio Brown, Markus Wheaton and Sammie Coates in a race). Shazier could be an All-Pro in 2016.

San Diego: Jason Verrett, CB

Last season Verrett, San Diego’s 2014 first-round pick, out of Texas Christian, proved himself to be the rare corner who can cover No. 1 receivers one-on-one. His body control and understanding of coverage angles were outstanding. The 5' 10", 188-pound Verrett is also nimble enough to cover his man if he shifts into the slot, and that opens up another range of possibilities for the entire defense. Because San Diego’s other corners—Casey Hayward, who was signed from Green Bay this off-season, and returning veteran Brandon Flowers—also have slot skills, the Bolts can now play a true man-to-man, with each corner matched to a specific receiver no matter where he lines up. Defensive coordinator John Pagano prefers a scheme built on deception and aggression. Expect to see much of that with this trio, led by its top-shelf star.

San Francisco: NaVorro Bowman, LB

With rampant questions about the offense, the 49ers will lean heavily on their defense in 2016 (particularly considering how often Chip Kelly’s up-tempo O compels his D to be on the field). The best player on that unit is inside linebacker NaVorro Bowman. Last season, returning from a horrific left-ACL and -MCL injury suffered in the ’13 NFC championship game, Bowman was a first-team All-Pro—just as he was for three straight years before his injury. Perhaps because he was on the voters’ minds last year, they slightly overrated him; Bowman was up and down, especially early on. He was creaky when changing directions, and his typically razorlike play recognition sometimes failed him. (He excelled down the stretch.) At his best he is a difference-maker, not just against the run, but also as a blitzer and in coverage (usually defending backs). It’s imperative that Bowman play at his old high level for the Niners to succeed.

Seattle: Earl Thomas, S

Most pundits find it impossible to pinpoint a single most valuable player on the Seahawks’ stacked defense—but the name you hear most often is Earl Thomas. The seventh-year free safety is easy to overlook because so much of his impact is found in what doesn’t happen—the routes he takes away, the coverages he rotates in and out of, the rushing lanes he fills in order to turn a 30-yard run into a less damaging 12-yarder. One of the unique dimensions of Seattle’s scheme is that its deepest defender does not always play in straightaway centerfield. Against formations with extra wideouts Thomas cheats aggressively to the strong-receiver side. This puts him in a more direct line of help-coverage positioning—but it also means he has more ground to cover if the ball goes the other way. Many D’s can’t make that work, but Seattle’s can because Thomas’s range and awareness are unmatched.

Tampa Bay: Doug Martin, RB

In an era of wide-open passing, Doug Martin is a throwback runner in a throwback offense. Martin is at his best rushing between the tackles; no one locates and slithers through small cracks as effectively as he does. While today’s backs prefer to operate out of spread formations, which create more space in the box, Martin, who is shrewd at setting up blocks and reading angles, is better in heavier sets, with more bodies around him. The Bucs’ system is conducive to this. Because Jameis Winston is a slower-twitch fastball thrower who needs time in the pocket, and because receivers Mike Evans and Vincent Jackson are big-bodied but also slower-twitch playmakers, Tampa’s passing game features deep drop-backs and deep routes that use the heavier sets Martin prefers. It’s an old-school system, one in which the back’s style fits perfectly with that of the QB and receivers.

Tennessee: Jurrell Casey, DT

Take a gander at Casey, and you see a bowling ball with arms and legs. You’d never guess that the 6' 1" 305-pounder is one of the most versatile defensive players in football. Casey, a sixth-year tackle from USC, gets off the snap quickly, and he has a knack for getting under a blocker’s pads and disengaging from contact. He can change directions extremely well in confined areas, and he finishes plays with authority. Last season legendary Steelers defensive coordinator Dick LeBeau took over Tennessee’s unit and used Casey in a variety of ways. In addition to lining up inside, he occasionally set up wide off the edge and, even more surprisingly, sometimes stood up as a roving blitzer—and he looked good doing it, underlining the disconnect between his appearance and his play. Now that Casey has experience in LeBeau’s scheme, don’t be surprised if his role expands in 2016.

Washington: Jordan Reed, TE

The Redskins have one of the most creative downfield passing schemes in the NFL, and the biggest reason is the 26-year-old Reed. A third-round pick in 2013, Reed has blossomed into the preeminent route runner at his position, and it’s not even close. Coaches tend to pause when describing Reed because they can’t help but make awkward comparisons with Aaron Hernandez, Reed’s predecessor at Florida. Like Hernandez, Reed has an uncanny smoothness. No linebacker and few safeties can guard him one-on-one; even corners find him to be a handful. Washington builds formations around the mismatches Reed creates. You’ll often see him split wide, forcing the defense to tip its hand: If a safety lines up across from him, it’s likely man-to-man; if it’s a corner, it’s zone. Kirk Cousins not only benefits from that presnap information but also from having Reed in a favorable matchup outside.

Photos: AP and Getty Images