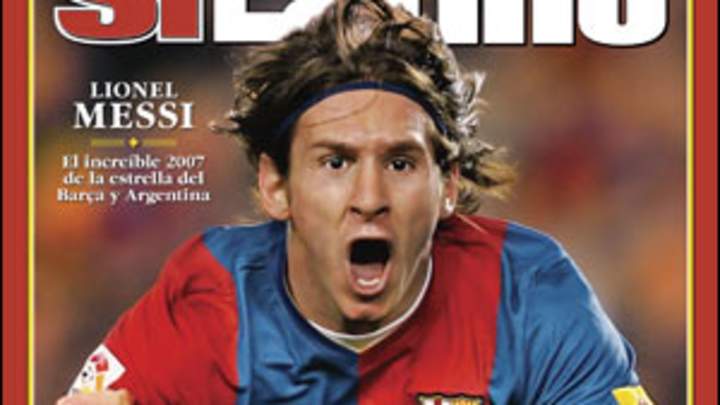

Hail the new king

All professional soccer players, except perhaps for goalkeepers, score at least one great goal during their career. The good strikers, if they're lucky, will score one that goes down in history.

The difference between them and 20-year-old Leo Messi is that he has his whole career ahead of him but has already scored three goals in 2007 that will endure as works of art to be admired in the museums of soccer 500 years from now, just like we admire Leonardo da Vinci today.

The first one was for Barcelona in March during the Spanish League derby against Real Madrid. It was the last minute of the game, and Barça, playing a man down, was losing 3-2. Messi got the ball outside the box. Madrid's attack and defense had retreated; its only objective now was to stop the equalizing goal.

With a lightning dribble to the left, Messi flew past one frozen opponent, left another one on the ground and penetrated the area. He still had to beat Sergio Ramos, the best Spanish defender, and Iker Casillas, the best keeper in the world. Messi sped past Ramos, who also fell to the pitch, and put a left-footed cross into the corner of the goal, just inside the far post. Casillas had no chance.

It all happened in the blink of an eye: Messi's third goal of the match, the equalizer that instantly made him, to the millions of fans following the game on TV, one of their favorite players in the world to watch.

That was the first course, light and tasty. The main dish, the following month, was pure protein, a juicy steak from the Pampas. It was the goal, that goal against Getafe in the Copa del Rey; the one that mimicked nearly step by step the best goal of all time: Diego Maradona's second score against England in the 1986 World Cup in Mexico.

There's no sense in describing it, since anybody who hasn't seen it would not be reading these lines. Suffice to say that Messi received the ball at midfield on the right flank and dribbled past the whole Getafe defense, including the keeper. Another goal seen around the planet. Twenty times.

And the third, dessert, was the one he scored for Argentina against Mexico in the Copa América semifinals in July. This one only needed two touches, the first one in order to control the ball while sprinting to the edge of the Mexican area; the second one, still in full speed, a sublime chip.

The whole stadium, including Mexican goalie Oswaldo Sánchez and defender Johnny Magallón, was expecting a low line shot or a pass down the middle to Carlos Tévez. Instead, Messi tapped the ball with the tip of his left cleat, lifting the ball in a geometrically perfect arch that grazed the crossbar before going into the net. It was pure instinct, pure genius. The connection between Messi's brain and his left foot -- at the moment his legs reached their full stride -- was a hymn to the marvelous complexity of human biology.

Away from the pitch, dressed as a civilian, with no ball in sight, Lionel Andrés Messi is unremarkable. Pale and on the short side -- but with ripped shoulders from working out at the gym -- he shows up for an interview in an anonymous room at Camp Nou, Barcelona's stadium, wearing a yellow T-shirt, jeans and white sneakers.

Without any piercings or visible tattoos, and with a haircut that lacks the faintest inkling of inspiration, Messi is the anti-Beckham. He is not a sex symbol; he is a soccer symbol. On the pitch, he is a god; outside of it, one more kid from Rosario, the industrial city 180 miles northwest of glamorous Buenos Aires.

How does one become so good at soccer? "Well," he says, with a thick Argentine accent that seven years in Barcelona have not changed a bit, "first of all you have to like it a lot." How much? "Well ... since I was 3 years old, I've been playing morning, afternoon and night. Inside the house as well. I would break things. My mom would get mad."

Does he continue playing inside the house? "I do," he says, with a slight and timid smile. (Messi is not Ronaldinho; his face lights up only when he scores.) "Yes, I'm still like that. At home, wherever, I have to have the ball near me, be able to touch it." Caress it, in the Brazilian style, as if it were a woman? Messi nods, but looks away to hide another smile.

Besides loving the game, Messi says, he had to work hard and sacrifice. Sacrifice? When he was making a living doing what he loved? He gets worked up for the first and only time in the interview, betraying a hint of indignation.

"Yes, sacrifice," he says. "I was 13 years old when I had to leave Argentina, leave behind my friends and a good part of my family to come to Barcelona. Though my parents came with me, it was hard at that age."

It was also necessary. Messi would have been even smaller and skinnier -- his nickname, after all, is Pulga, or flea -- had it not been for the human growth hormones doctors recommended for him as a kid. Those were prohibitively expensive for his family and the Rosario football club, Newell's Old Boys, that nurtured him as a player, but not for FC Barcelona, which ultimately paid for the treatment.

When Messi showed up at the Catalonian club in late 2000, coach and former player Carles Rexach watched only five minutes of his tryout before saying: We'll keep him. Messi had the physique of a 10-year-old but a prodigious talent that earned him his debut on the first team at age 16.

"The Barcelona youth system is one of the best in the world," he says. "They teach you not so much to play to win, but to grow as a player. That's why, as opposed to the experience I had in Argentina -- where it was more physical -- every day you would train with the ball. I barely did any running without the ball. It was an extremely technical training."

Barcelona's investment began to pay off in the '05 preseason, when Messi, then 18, cracked the starting 11 for the first time at Camp Nou in a friendly against Italian powerhouse Juventus.

"That," says Messi, "was the day people began to hear of me." Anybody who watched the game between these two star-filled teams knew that Messi was something special. He was the player of the match. Fabio Capello, then coach of Juve, added his voice to the chorus of praises by asking, Where did this diavolo come from?

Capello used the right word. There is diabolical mischief in Messi's game, a savage, indomitable quality. That's why, anticipating the next Barça-Real derby, on Dec. 23, current Madrid coach Bernd Schuster said, "I'll have to put my dog's leash on him to calm him down."

If David Beckham were a dog, the problem wouldn't be so much the collar as the hair. The Englishman, whose fame is utterly disproportional to his talent, is a great athlete who, through perseverance and repetition, has become a dead-ball expert. Messi is a live-ball expert. He is soccer in its natural state: the schoolyard genius, übertalented in the fundamental art of the dribble.

Even Ronaldinho, his brilliant teammate, is more of a studious player who deliberately, as he freely admits, imagines plays before they develop. Not Messi. Messi is spontaneity incarnate. "I don't watch games afterwards on TV," he says. "They say it helps you correct your mistakes, but not me."

He also doesn't fixate on other players, though he has a weakness for fellow Argentine Pablo Aimar. "But I don't try to imitate anybody; the way it comes out is how I play," Messi says.

That may be why neither his opponents nor his teammates ever know what to expect from his left foot. "Each game you ask yourself, How did he do that?" Gabriel Milito, Messi's teammate on Barça and the Argentine national team, told the Madrid newspaper El País. "In my first training session with the national team, I knew he was different from all the rest. I've played with some of the best, but no one like Leo."

That's saying a lot. With Argentina, Milito plays alongside players of the caliber of Tévez and Juan Román Riquelme, and in Barcelona he shares the pitch with the Fantastic Four. One of these is Messi; the others are Ronaldinho, Thierry Henry and Samuel Eto'o. But even they are struck dumb by talent of their young teammate. Eto'o says that Messi is like a cartoon character. Henry admits that when Messi is on the field he runs the risk of becoming a mere spectator: "I have to be careful not to stop to watch his moves."

Ronaldinho, who knows firsthand the virtues of fellow Brazilian Kaká, believes that no one is more deserving of the award for best player in Europe -- and by extension the world -- than the Argentine. "I've seen Messi's evolution, and I vote for Leo to win the Golden Ball," he said.

That evolution is manifest in the sheer range of Messi's skills. First of all, he is scoring more and more goals. After his hat trick against Real Madrid in March, he has scored an average of almost a goal per game. Second, to his incredible repertoire of dribbles he is adding a vision that befits -- and benefits -- Ronaldinho himself.

If you take a close look at the few bursts of magic that the Brazilian showed in '07 with Barcelona, they came from electrifying exchanges with Messi: give-and-gos or laserlike passes, the kind that create goals and that distinguished Maradona later in his career.

That's why Messi today is considered by his teammates and the Camp Nou faithful as the leader of Barcelona. He has ceased to be the lone ranger on the right wing and become -- despite being the youngest player in the starting 11 -- the sheriff, the one who inspires, creates and scores.

Yet he remains humble, a trait he must keep cultivating if he wants to fulfill his enormous potential and become not only the best player of his time but also a rival in the history books to his legendary predecessor at the Catalonian club, Johan Cruyff, and even to the sacred troika of Pelé, Maradona and Alfredo DiStéfano. For all of those reasons, Messi is SI Latino's 2007 Sportsman of the Year.

"There's much I need to improve," Messi says. "For instance, shooting with both feet. My right-footed shot still needs some work. And to be able to take free kicks like Ronnie."

Does he hope that someday everyone will consider him the best player in the world? "It would be nice, but it's not something I'm obsessed with," he says. "Most of all I think of how fortunate I am. I thank God for everything He gives me, and for having the good fortune to play alongside these teammates in Barcelona and the national team."

Their sentiments exactly.