The Year in Sports 2007

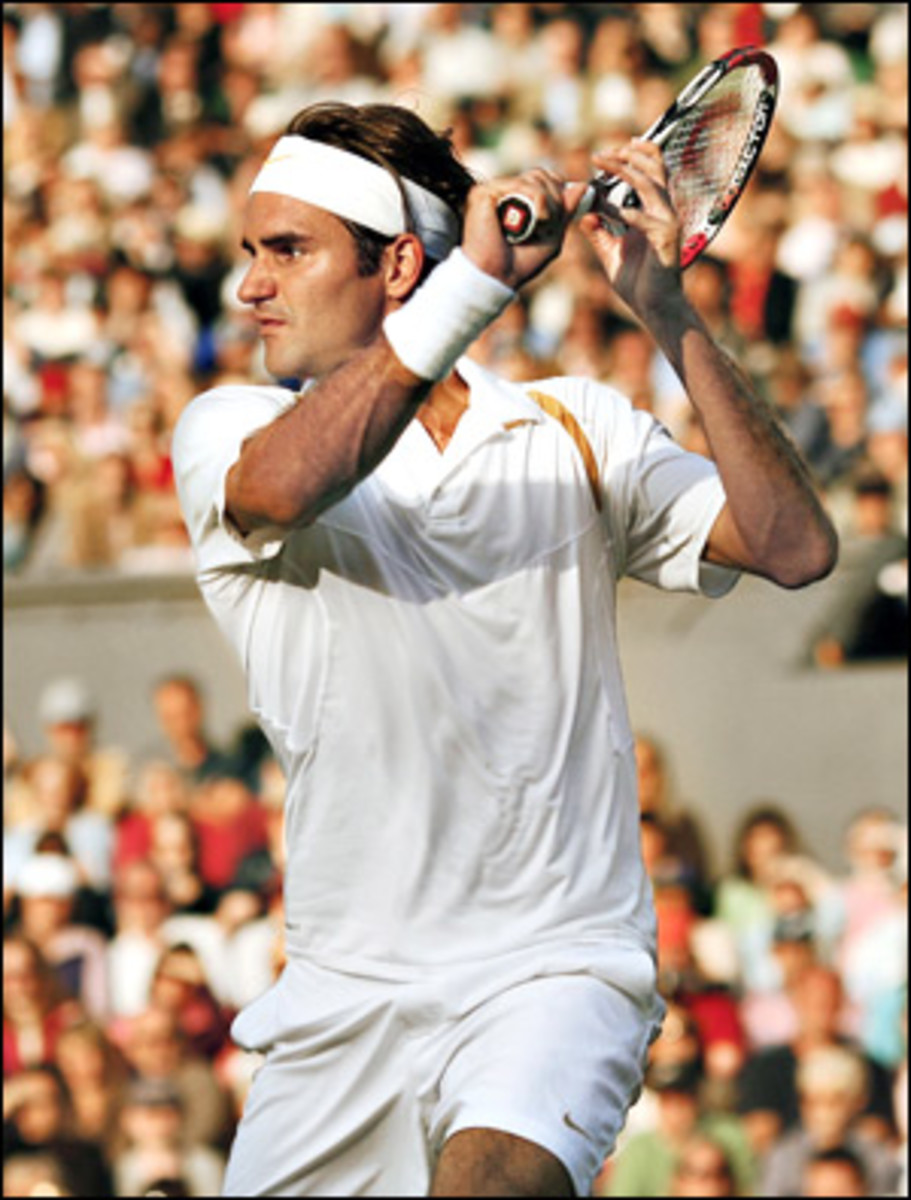

Cartwheeling with topspin, the ball made a hard left turn as it skidded off the grass, seemingly headed for the courtside flower boxes. In full stride Roger Federer caught up with it and, in one fluid motion, cocked his racket and fired a forehand past Rafael Nadal that nearly left a divot when it bounced inside the baseline. It was midway through the fifth set of the Wimbledon final: the most important moment of the most important match of the most important tournament in tennis. If ever there were time to conjure sensational shots, this was it.

Until that afternoon of July 8, 2007, one could have made the case that Federer had never had a moment of truth -- a gut check, as a high school football coach might call it. Sure, the Mighty Fed had done an almost absurd amount of winning over the past few years, taking 10 of the last 16 Grand Slam singles titles, reaching the finals of the last nine majors and, for all intents and purposes, ending the who's-the-greatest-player-ever debate. But it all seemed to come so easily to him. Consider the 2007 Australian Open, which Federer won without dropping a set. As James Blake joked last spring, "I still don't think I've seen Roger sweat."

That summer afternoon at the All England Club, Federer was sweating. Four weeks earlier he'd lost to Nadal, the grind-and-pound Spaniard, in the French Open final. While that defeat stung, it wasn't altogether unexpected given that clay is Federer's least favorite surface. But were Federer to fall to his rival on the lawn of Wimbledon -- well, that would alter the balance of power in men's tennis. And it would amplify the whispers that for all the calligraphic beauty of Federer's tennis, he lacked a taste for combat.

Yet fired up by that masterly running forehand, which broke Nadal's serve to give Federer a commanding 4-2 lead in the fifth set, the world No. 1 cruised through the next two games. Within 15 minutes he was dropping to his knees in victory, and all was right with the tennis world. Federer had won Wimbledon for the fifth straight time, and two months later he would win his fourth consecutive U.S. Open. He finished 2007 within two titles of tying Pete Sampras's record of 14 career majors.

All told, it was a typically gilded year for Federer, not appreciably better or worse than the preceding one. But his display of mettle in the critical moments of the Wimbledon final marked this season as the one in which Federer was not merely a winner but also a champion. -- L. Jon Wertheim

The first whiff of suspicion came as the money poured in. Playing a small ATP event in Poland last summer, Russia's Nikolay Davydenko, then the world's fourth-ranked player, faced Martín Vassallo Argüello, the 87th-ranked journeyman from Argentina. A match of this nature typically attracts about $700,000 in wagers, made largely online and mostly in Europe; yet nearly $7 million in bets, most of them by nine Russians, were placed against Davydenko. Then, when the match got under way, the alarms really clanged. Davydenko won the first set handily, yet bets against him kept coming in. Surprise, surprise: He lost the second set and retired in the third with a foot injury. In an unprecedented move, the British gambling company Betfair voided all bets, citing the dubious patterns. The fix, many suspected, had been in.

Despite his impressive ranking, Davydenko was so little known that he lacked a footwear sponsor. Suddenly his name made headlines around the world as he stood accused of throwing the match. (Davydenko has steadfastly asserted his innocence.) As the men's tour's CEO, Etienne de Villiers, repeatedly insisted that "the sport does not have a corruption problem," player after player emerged with accounts of phone calls in which they were asked if they'd like to make money by throwing a match. "I don't know if it's the same person, but I think everybody gets contacted," 32nd-ranked Dmitry Tursunov told SI in September. "And whether you act on it or not, it's a problem."

Tennis is a sport primed for a betting scandal. The players are individual contractors who need not conspire with teammates before throwing a match -- nor answer to owners afterward. And even the best players can commit dozens of unforced errors every time they take the court. Who's to say if a player is tanking or simply having an off day? Certainly not ATP officials, who docked Davydenko $2,000 for "lack of a best effort" in a loss to 71st-ranked Marin Cilic in St. Petersburg in October -- only to rescind the fine on appeal. If there's a silver lining to the match-fixing allegations, it's that they appear to be confined mostly to lesser players (Davydenko notwithstanding) at lesser events. Still, this is one racket that tennis could definitely do without. -- L. Jon Wertheim

Only in tennis does the de facto players' association profess ignorance when one of its biggest stars flunks a drug test. On Nov. 1 Martina Hingis announced that the International Tennis Federation (ITF) was reporting that she had tested positive for cocaine after a urine test at Wimbledon. And while Hingis claimed that a hair test had exonerated her, she said that rather than "fight this doping machinery," she would retire from the sport immediately. Mere moments later the WTA issued a press release contending that it had "not received any official information regarding the positive doping test." -- L. Jon Wertheim