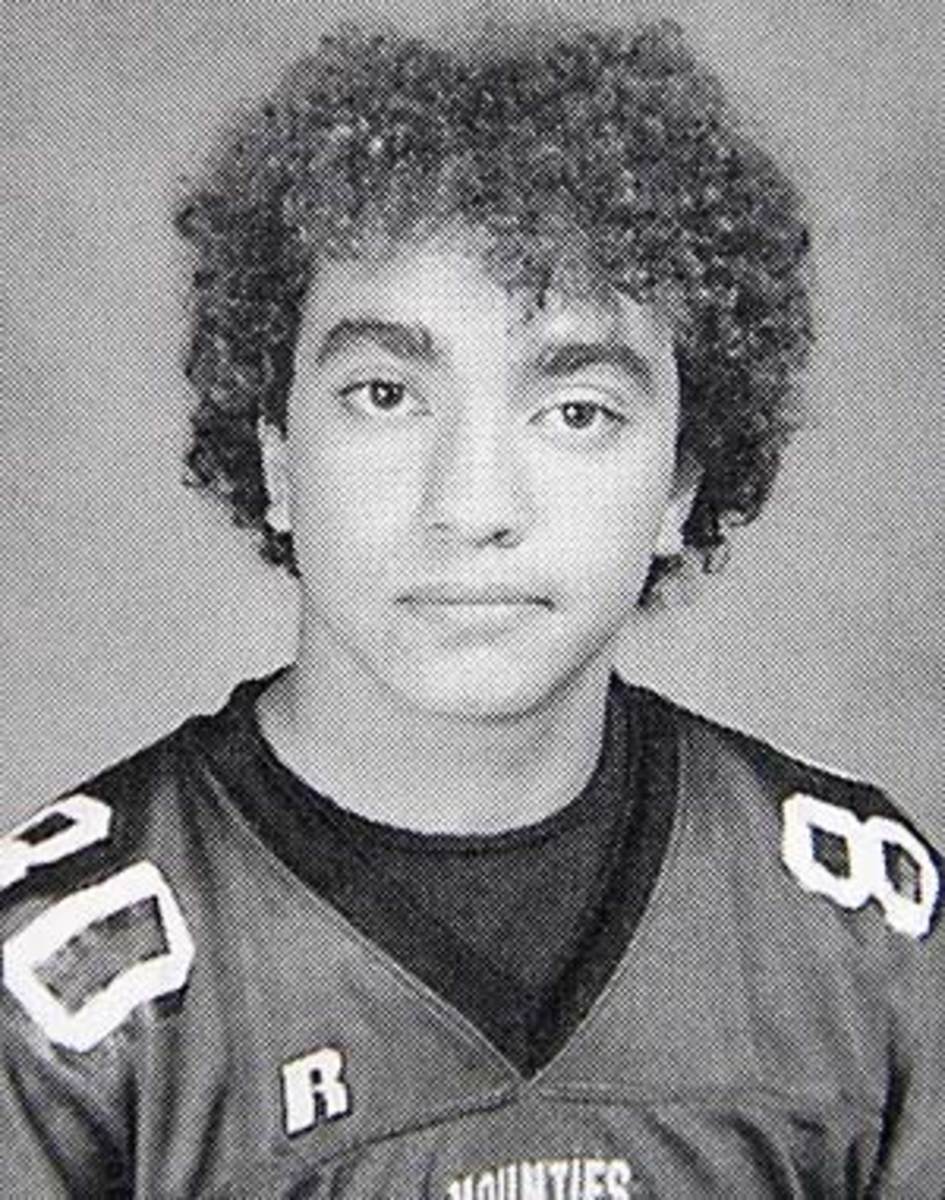

N.J. parents file lawsuit for son being cleared after concussion

Now, nearly a year after his death, Dougherty's parents have filed a lawsuit against Montclair High and their son's physician, who they say cleared him to play after the concussion. The lawsuit alleges that Dougherty failed a test that can detect lingering concussion symptoms -- a test that a Montclair High certified athletic trainer says was deemed invalid because a disruptive athlete distracted test-takers -- and that he should not have been allowed to return to play following the concussion.

The lawsuit, filed in Essex County civil court on Sept. 23, alleges that two weeks before he died -- after the first blow and before the second -- Dougherty failed an ImPACT test, a computer-based exam that tests memory and concentration to assess whether someone has fully recovered from a concussion.

According to Montclair High personnel, the fact that Dougherty took the test was coincidental to his having suffered a concussion -- last fall the school was beginning a program to test all athletes, and Dougherty was tested with a group of students -- and that it was not meant to determine whether he was still suffering from his prior concussion. Additionally, according to Michele Chemidlin, a certified athletic trainer at Montclair High, Dougherty's test was never evaluated and the score was deemed void. "We actually had a problem in the room he was taking it, and all those tests became invalid," Chemidlin says. "Another athlete [in the testing room] was being disruptive to everybody, so those people had to retake the test."

Dougherty took the test last fall as part of Montclair High's nascent effort to implement neurocognitive testing for concussions, and to have all athletes establish a baseline score on the ImPACT test. Once an athlete has a baseline, he retakes the test after a hit to the head, and if he does not score close enough to his baseline, then he should not return to play. A second concussion shortly after the first can cause serious and long-term effects, according to scientific studies. In rare cases, teenagers, whose brains are not yet fully developed, will die from "second impact syndrome," swelling in the brain that results from a second head trauma before symptoms of the first have completely cleared.

Even though Dougherty only took the test once, his test -- discounting distractions -- theoretically could have been used to gauge whether he was still suffering symptoms. According to Kenneth Podell, director of neuropsychology and the Sports Concussion Safety Program at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, and one of the creators of the ImPACT test, results come with national data divided by age-group, and a low percentile score could raise concern.

"It's up to interpretation what you consider low," Podell says, "but anything below the 16th percentile should raise eyebrows." Podell added that if a student who does well in school scores low, that might add to the suspicion that he or she has not recovered from a concussion. Dougherty was reportedly an honor student at Montclair.

Dougherty's ImPACT score is not public, but it could be revealed if the lawsuit goes to trial. An attorney representing Dougherty's parents declined comment on their behalf.

Because of the disruption during the test, Chemidlin says, the scores from that session were never analyzed. The ImPACT test requires a quiet environment that allows the test-taker to concentrate and react quickly to questions. According to the lawsuit, "Ryne's October 2, 2008 ImPACT test revealed objectively abnormal results," and had they been evaluated "Ryne would not have been permitted to play."

Dougherty suffered the initial concussion during a game on Sept. 19, 2008. According to the lawsuit, he took the ImPACT test at school on Oct. 2, and was examined by his personal physician, Michele Nitti, "on or around Oct. 3." It is unclear from the lawsuit whether or not Nitti was given Dougherty's ImPACT results, or even knew that he took the test.

The lawsuit alleges that Nitti cleared Dougherty to play "despite the fact that Ryne complained of fatigue," and that Montclair High allowed him to play even though he had allegedly "failed the ImPACT test from Oct. 2, 2008." Dougherty was cleared to play on Oct. 6, and suffered the fatal blow in a game a week later. Nitti did not respond to a message seeking comment.

Last year teammates said that Dougherty complained of headaches even after he was cleared, and in an interview last year with SI, Dougherty's mother, Marinalva Schnarr, suggested that her son hid symptoms from doctors so that he could return to the field. "He wanted to play football so bad," she said. "That's why he [told doctors] he felt fine."

The ImPACT test, however, is designed to reveal lingering concussion symptoms even if the test-taker is attempting to hide them. If, following a hit, an athlete cannot score close to the baseline, then the athlete is not ready to return. Only around 2,000 of the more than 23,000 high schools in America use the ImPACT test. Many schools do not employ the test because of the cost, the lack of a certified athletic trainer to administer the test or the fact that such testing is not considered part of the standard of care.

According to John Porcelli, Montclair High's assistant principal in charge of athletics, the school is currently requiring ImPACT baselines of all athletes before they are allowed to play. Porcelli said that he had heard that a lawsuit might be in the works, but was not aware that it had been filed until SI informed him of it this week. He noted that Montclair has been especially proactive since Dougherty's death. Last winter the school brought in Dean Filion, a doctor who works with the New York Giants, to educate coaches on concussion management.

According to Podell, who did not evaluate Dougherty and is not involved in the case, the timeline of events in the Dougherty case raises potential concerns. Since Dougherty had been concussed on Sept. 19, he should not have been taking a baseline test two weeks later. Any lingering symptoms or deficits would prevent the score from providing a valid baseline. Podell, who works with athletes ranging from high school to the pros, says that he tries never to give a baseline test to an athlete in-season, on the chance that the player has been dinged recently and will not score an accurate baseline. If he knows a player has been concussed, as Dougherty was, Podell will wait months before administering a baseline test. He added that if there are disruptions during the test, as Chemidlin says occurred during Dougherty's exam, the baseline test could be invalid and would have to be redone. Porcelli and Chemidlin say that Montclair High's ImPACT testing was just ramping up last fall, and Dougherty, who was simply taking the test along with other athletes as part of the new program, did not retake the test in the week and a half before he was hit and collapsed on the field.

Podell added that Montclair High should not have considered Dougherty's Oct. 2 test to be an accurate baseline in any case, because he was not cleared by Nitti to participate until Oct. 6 , and thus he could still have been suffering symptoms. Instead, Podell says, Dougherty could have been given another kind of ImPACT test -- a post-concussion test that the University of Florida recently used as part of its battery of exams to determine the readiness of quarterback Tim Tebow -- which is similar to a baseline test but is administered individually and by a doctor, not in a group at school.

After Dougherty died, Montclair's then-interim principal, Judith Weiss, told TheNew York Times that Dougherty had been given a CT scan by doctors before he returned to play. But according to medical experts, concussions do not typically show up on brain images, and a CT scan is not considered diagnostic for concussions. The details of how Nitti evaluated Dougherty before allegedly allowing him to return to competition are not currently public.

Podell says that doctors should be sure to test factors such as memory, concentration and balance, and that, upon exertion, symptoms could return to an athlete who was symptomless at rest. Thus, he says, clearance should not be granted until symptoms have disappeared not only at rest but also throughout a specific return-to-play protocol that includes cardio training, non-contact practice and, ultimately, contact practice. "When you're rested, sometimes the brain has enough power left in it to normalize," Podell says, "but as soon as a challenge to the body causes blood flow to be redirected, the brain can't compensate and symptoms return." Podell says that doctors who deal with athletes should be sure to do exertional testing, and not simply to "do a cranial nerve examination. You can check eye movement and pupil size...but the cranial nerves are intact unless you're really badly concussed."