Dr. Z’s All-Time Team: Part II—Defense and Special Teams

This week The MMQB is celebrating the life and career of Paul Zimmerman, the longtime Sports Illustrated writer known as Dr. Z for bringing a groundbreaking analytical approach to coverage of pro football. For Part I of Dr. Z’s All-Time Team—Offense, click here. For all of the stories from Dr. Z week, click here.

* * *

ALL-TIME TEAM: DEFENSIVE END

We have flipped over to the defensive side of the ball, and we’re entering the world of specialization. This is what drove the editors crazy, my battery of designated skills. I wish to apologize, for those and for the various ties I’ve awarded, but there really are different positions within one label. Reggie White moved around all over the line during his career, but he always came home to the power side, left defensive end, because he could play the run, could stand up to a tight end with double-team intentions, could penetrate and throw a large shadow over the quarterback’s primary field of vision—the “front side,” it’s called.

Once I watched Eagles game film with him in his home in the Philadelphia suburbs, and he pointed out the minefield he had to dance through on practically every play. It was like watching a matador trying to take on three or four bulls. They set him up, turned him, dove at his knees, hung out and waited for blind-side hits, and I realized that this wasn’t just a big guy getting by with a variety of moves—speed rush, bull rush, his patented “hump move,” etc. It was a case of agility translating into survival. One particularly vicious looking play, against the Giants, when his back was half turned and one of the tackles drew a bead on the back of his knee and White just turned his body at the last minute to avoid the death blow, got me to instinctively cry out, “Watch out!” He got a laugh out of that.

“Is this normal?” I asked him.

“Not against every team,” he said. “With some others, though ... every game, every play.”

The argument against Deacon Jones and Richie Jackson is that they had the head slap to help them on their way to the quarterback. My argument is that even without that move they would have found a way to get in because they were such great competitors, such great athletic specimens. Neither argument is right or wrong, it’s just the admiration I share about the days when I was watching these two great players.

I think Deacon made more crawling sacks than any player who ever lived. When he was knocked off his feet the argument was just starting.

“The main thing is to keep going,” he said. “If I get blocked, I’ll claw my way in, even if I have to crawl.”

He was a run player, too, of course ... they all were in those days when the ground attack was big, not just a change of pace. Not many disputed the claim that he was the greatest defensive end of his era.

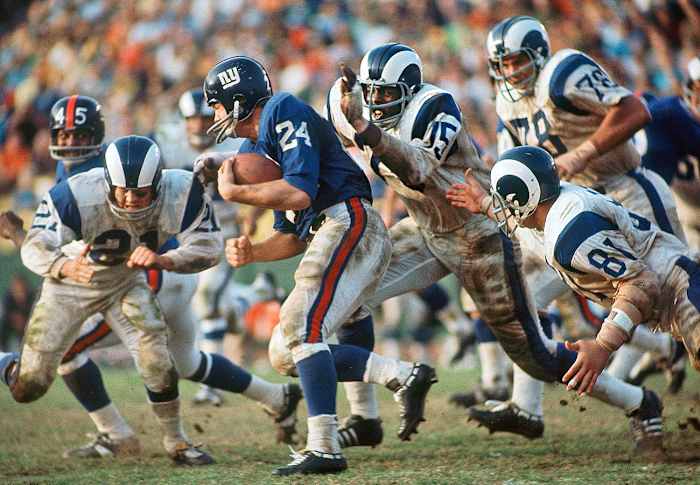

Deacon Jones attacking the Giants’ Tucker Frederickson, November 1968.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

But Jackson occupies a special place in my memory because 1) no one ever heard of him, since he was an outlander from one of the AFL’s backwater franchises, and 2) he has never reached any serious level of Hall of Fame consideration, despite my lobbying for him every year in the preliminary balloting, mainly because knee injuries took the heart out of what could have been a glorious career.

Two stories stay with me. The first one was told to me by Stan Jones, who was the Broncos’ defensive line coach in 1967. The team had gotten Jackson, a nondescript linebacker and tight end for the Raiders, in a five-player trade.

“I was sitting on the porch of our dorm after dinner,” Jones said. “He pulled up in this old jalopy he’d driven nonstop from Oakland, 24 hours over the mountains. I looked at him and told him, ‘You seem a little big for a linebacker. I think we’ll try you at defensive end.’

“He was 26 years old. He’d been in the minor leagues for a while. He just stared at me and said, ‘Mister, I’m gonna play somewhere. I’ve driven as far as I’m gonna drive. Here’s where I make my stand.”

And he did. He became “Tombstone,” one of the most respected DEs in the game, “He was our enforcer,” said Lyle Alzado, who’d been on the same defensive line. “If a guy was Hollywooding you—you know, trying to show you up—they’d move Richie over to him and he’d straighten the guy out. The Packers had this 6’8” tackle, Bill Hayhoe. I faced him when I was a rookie, and he was grabbing me, jerking me around, making fun of me. I was having a terrible time. Richie said, ‘Lyle, is he Hollywooding you?’ and I said yeah.

“He moved over for one play. That’s all it took. He knocked him to his knees and split his helmet wide open. Remember that famous picture of Y.A.Tittle on his knees, with blood dripping down his nose? That was Hayhoe. They had to help him off the field.”

Howie Long will not get many votes for the all-time team because it’s generally picked by sack totals, and his were not impressive. Oh, he’d line up on the power side and jam up the run, and then move inside and face the meat grinder when he was called upon. He’d do all the nasty things, and if they awarded sack statistics in a fair manner, by sacks caused, not inherited, his totals would be out of sight, because he flushed a million quarterbacks into other peoples’ arms. He just never was a great tackler himself. He used to register a certain amount of bitterness when he’d read about some defensive end who was being plugged in as a wide-, or open-side, pass rusher.

“Just once in my life I’d like to see what that’s like, spending a whole season rushing from the open side,” he’d said. “What’s the record for sacks in a season?”

One more DE and then I’ll let it go. This concerns a freak player who could rush the passer and do very little else that endeared him to his teammates. Mark Gastineau of the Jets, hated by his fellow linemen because he would not run his inside stunts, taking it inside where the big boys lived. “I’m doing my thing,” he’d tell them. But man, what a pass rusher.

First of all, he had speed in the 4.5s to go with his weight, which was in the 290s. I’ve watched him in practice, during half-line drills, put on a relaxed kind of rush, with a dreamy look on his face, and come in untouched. I mean clean. Over and over again, and I’ll swear that it looked as if he was just walking fast. The problem was that offensive linemen simply could not judge his speed or his change of pace. A freak.

* * *

ALL-TIME TEAM: DEFENSIVE TACKLE

Defensive tackle is a confusing position these days. You’ve got nose men playing a zero-technique, two-gap defense, and three-technique tackles, playing a one-gap, plus all manner of varieties. You’ve got base players who might be on the field for only the first play of a series and “reduced ends,” who would line up as a tackle, on the last one. It makes it confusing when you’re trying to pick an All-Pro team, because first, you have to locate your guy on the field, after you’ve made sure he was there in the first place. If you want, you could get real technical and pick a battery of players, one for each technique, or you could get lucky when someone makes it easy for you by excelling in all of them.

Such a player was Pat Williams, who started his NFL life as a sleek, mobile, 270-pound Buffalo Bill and gradually grew to a sturdy Minnesota Viking in the 320 to 330 range. In 2005 he had one of the greatest seasons I’ve ever seen a DT have. He could play the nose, and I saw him leave a trail of destroyed centers around the league, including Chicago’s All-Pro Olin Kreutz. He could move outside the guard in the three-technique and penetrate quicker than he could be blocked. He wasn’t like one of those typical, situation fat guys who gets yanked after his base, first or second down play, and spends the fourth quarter on the bench, sucking oxygen. He turned it on for all four periods.

I named him my defensive player of the year. I thought he was the most impressive power tackle I’d seen since the heyday of Merlin Olsen, and do you want to know what kind of postseason awards he reaped? None. Sackers get the glory. He had one sack. Of course, after he had established his credentials he got a steady diet of double-teams, but that was OK, he still collapsed the pocket and forced the QB onto other peoples’ sack statistics.

I’ve picked sacking tackles on my All-Pro team, but only if their run grades measured up. That’s why I never was as high as other people were on Alan Page, who had more sacks than any other tackle in history. Against the run, he was a liability. Pure rushers who, like ex-Viking John Randle, said they’d “pick up the run on the go,” were persona non grata. He never made the Sports Illustrated All-Pro list.

“All you’re doing,” said Mike Giddings, a high-powered personnel consultant for 13 NFL teams, “is neglecting the most dominant interior rusher in the game. And that’s what the game is, whether you like it or not ... pass rush and pass protection.”

My reasoning, which I tried to explain to him, was the following, and I had seen this so many times: First play the enemy runs is a trap at Randle. He’s so far out of position he takes himself and the guy next to him out of the play. Plus eight for the opponent. Second play is a draw aimed at you know who. He’s upfield and moving fast, when the back goes by without stopping to wave. Plus five. Third play is a pass, and Randle, showing a remarkable spin and burst move, sacks the QB for a six-yard loss and pounds his chest, to deafening roars (if it’s a home game). He has his sack and he can retire for the afternoon, and a season of those kind of games would give him 16 sacks, a huge number for a DT. All-Pro of course, but to me he is seven yards in the hole ... 13 allowed, six accounted for.

Now look at my trio, please— Merlin Olsen, Bob Lilly, Joe Greene. No excess weight hanging over the belt, skilled in all phases of the game, never off the field. Am I being simplistic? A lost soul crying for a less technical age? I don’t care. These are my guys. Lilly’s game represented near-perfect technique. A grabber and thrower, “hands that were so quick you just couldn’t beat him to the punch,” Dolphins guard Bob Kuechenberg said. A roughneck only when aroused or held to the point of madness. Tom Landry used to send weekly game films to the league office with special notations marked, “Holding fouls against Bob Lilly.”

Greene’s style was at variance with his name, Mean Joe. He could get nasty out there, but his game was based on quickness. So fast off the ball was Greene, so quick to penetrate, that the Steelers created a new alignment in his honor, the Cocked Nosetackle setup, in which Greene attacked the center-guard gap from an angle, or a tilted position. The bully boy on that defensive line, in fact the most feared player on the whole Steel Curtain Defense, was No. 63, Fats Holmes, the only player on that unit, oddly enough, who was never chosen for a Pro Bowl.

“After the game, just look at the condition of the guy who had to play against Fats,” Chuck Noll said. “That’ll tell you what kind of a player he was.”

Playing against Greene, the major fear was embarrassment, the whiff, the total miss, which happened more often than offensive linemen would like to recall.

Olsen was the quintessential bull rush tackle. Oh, you’ve got bull rushers now, but he did it play after play without letup, collapsing the pocket, piling up the run, breaking down the inside of the line while his teammate, Deacon Jones, mopped up outside. He was also one of the cleanest defensive linemen in the game. He hated nonstop holders, and especially cheap shot artists. The name of Cardinals’ guard Conrad Dobler would get him furious, even by casual reference. Once I told him that my newspaper, the New York Post, was doing a Dobler feature. And Merlin, who played all those gentle giants on TV, once his playing career was over, showed some real fury. “If you’re the one to write it,” he growled, “I’ll never speak to you again.”

Another time he admitted that Dobler’ s filthy tactics had forced him to do the only thing he ever regretted in 15 years of football.

“I arranged it with Jack Youngblood, the end playing next to me,” Olsen said, “that I’d set Dobler up and Jack would crash down from his blind side and cave in his ribs. Except that we weren’t very good at it. Dobler smelled it coming, he sensed it and turned at the last minute and Jack wound up hitting me. Dobler just laughed at us.”

“We should have practiced it a little more before we used it,” Youngblood said.

* * *

ALL-TIME TEAM: LINEBACKER

The year was 1968. I had just covered the Penn State-Miami game in State College, and I was in the Nittany Lions’ trainer’s room talking to Mike Reid, the junior defensive tackle. Miami DE Ted Hendricks would win an award for top collegiate defensive lineman that year, next year would be Reid’s turn, and we were discussing how a player as freaky looking as Hendricks could be so good. I mean, he was 6’7”, 215, and his technique was to kind of lean over things and pluck ball carriers out of space with his inordinately long arms. Even his nickname was freaky, “The Mad Stork,” not exactly designed to put fear into people, unless they were parents with too many kids, worried about more coming.

“He’s, well, the kind of guy you wouldn’t mind going down into the pit with,” Reid said, “but I don’t think you’d ever get a clean block on him, either.”

It proved to be a remarkably accurate forecast of what Hendricks’ life as an NFL linebacker became. He didn’t leave a trail of shattered bodies or a memory of ferocious hits, but he just played everything so well. He was seldom out of position, he could move backward and knock down passes with those long arms, or rush forward and smack them back at the quarterback. Everything was done from a plane of high intelligence; he had been a Rhodes Scholar finalist in college.

My lasting memory? Somebody, sorry but I can’t remember who, ran a reverse at him. Now this just wasn’t done, but it was tried, and Hendricks sniffed it out immediately, and when the ball carrier had finished moving parallel to the line of scrimmage and was ready to turn upfield, there was Hendricks, just standing there. All momentum had been lost. They faced each other. Hendricks shrugged and held out his hands, palm up, like, “OK, now what happens?” A huge roar went up from the Raiders crowd, which always cherished such moments. The runner dropped to a knee. Second and 16.

For a guy who played such a correct, technically sound game on the field, he was pretty wacky off it. I found out when I spent a hilarious week on Oahu’s North Shore one off-season, trying to do a piece on Hendricks, who was an instructor at John Wilbur’s football camp. It’s hard to remember everything that happened, or to read the notes I somehow managed to take. I seem to remember a place called Juju’s and something about fright masks and an amateur-hour type of evening...not sure I was involved in it or not, I do remember asking him about his place of birth, Guatemala City, where his father had been stationed.

“You’ve never seen flowers like that in your life,” he said, and then proceeded to name the species of Hawaiian flora in our area. Then he got this faraway look.

“You know something,” he said. “I really should have been a florist.”

OK, Hendricks, nicknamed “Kick ’Em” by his Raider teammates for one lamentable lapse of judgment, is my all-purpose outside linebacker. And now we move to the field of specialization. Jack Ham was the best pure coverage linebacker, with second place going to...oh, I guess I’d have to say Chuck Howley of the Cowboys’ Doomsday Defense. Ham lined up on the left side of the Steelers’ defense, which was kind of unusual, because usually that was reserved for the strongside LB, skilled at playing the tight end. Maybe it was Ham’s instinctive ability to cut through traffic and stack up the power sweeps to the right, a big part of NFL offenses in those days, that kept him there. Maybe it was because Andy Russell, the right-side linebacker, was also an open-side kind of player, but it worked out just fine. Ham was such a force in coverage, and against the wide plays, that even the All-Pro and Pro Bowl pickers, who usually grade linebackers on sack totals, could spot his greatness. He blitzed very seldom.

Coverage was so instinctive to him that it never seemed like much of a big deal. “Jack and I were sitting next to each other on the bench,” Russell said, “and we were talking about the market and he was telling me about some stock he really liked. Then we had to go out on defense. First play they ran, Jack read the pass and dropped into his zone, deflected the ball with one hand, caught it with the other as he stepped out of bounds, flipped it to the ref and overtook me on our way off the field.

“‘Like I was telling you,’ he said, as if nothing at all had happened, ‘you ought to look into that stock; it’s really a good deal.’ ”

Ham and I were once talking about Lawrence Taylor. “Sometimes,” Ham said, “I think his playbook was written on a match cover.” In other words, LT’s coverage responsibility, so important in Ham’s scheme of things, was almost zero. His career interception total was nine. Ham’s was 32. Taylor, basically a defensive end in college, wasn’t really a linebacker at all, although he is generally acclaimed to be the best ever. He was an outside rusher who would occasionally line up in a stand up position, the finest in history at this special role created by Bill Parcells and Bill Belichick on the Giants.

Later in their careers both coaches searched for other players to fill this role, which turned a 3-4 defense into a 4-3 and back again. Parcells tried it with Greg Ellis on the Cowboys, with Belichick’s Patriots it was Willie McGinest and then Roosevelt Colvin, basically down linemen who would stand up at times but really were pass rushers at heart. Taylor, of course, was the greatest.

I’ve written how LT, toward the close of his career, became introspective, even philosophical about the game. A couple of years from the end of his career, we got into a talk about how a player knows when the end is coming. “I’ll tell you how I know it,” he said. “The power rush starts going. That’s the thing that people never realized. I’d get lots of sacks in different ways, but the best came from straight power, driving right into a guy and lifting him, because he didn’t expect it from someone who weighs 245. It’s the starting point for everything, the base of operations. But when you feel that going, and right now I do, then you can tell things are coming to an end.”

I lobbied hard for Dave Wilcox at the Hall of Fame Seniors Committee meeting. His was an almost unnoticed skill as the eras changed, playing the tight end, actually nullifying him, avoiding getting hooked on running plays, the typical modus operandi of the classic strongside linebacker. I think the quote that swung it for him was one from Mike Ditka: “Wilcox was the reason I quit when I did.”

I had ammo from Mike Giddings, the super personnel guy, who’d been Wilcox’s linebacker coach on the 49ers. “Strongside linebackers get hooked to the inside now on running plays, and it just doesn’t seem to matter,” he said. “How many times do you think Wilkie got hooked? Never. It was a point of honor with him.”

That was part of it, of course, but trying to get him the nomination as the Senior candidate, and then getting through the major enshrinement voting, based on a platform of not getting hooked, well, I think half of them would have looked at me as if I were telling them that he stayed away from the ladies on Bourbon Street.

No, I think the strongest thing that emerged, in addition to the Ditka quote, was a battery of testimony that Giddings provided, statements from just about every Niner who ever lined up behind Wilcox, about how much he had done for their careers. Plus, of course, many quotes from opponents who respected the world of old-fashioned values that he represented. And to the credit of the selectors and the Seniors Committee members, there was just something about Wilcox and the humility he showed in doing a specialized skill better than anyone else ever had.

Oh, he could rush the passer if he had to. Giddings mentioned the game in which they decided to turn him loose on the quarterback and he had three sacks and two forced fumbles. It was just that he was too valuable in his regular job.

At one time middle linebacker was such a glamour position that All-Pro teams would have two, sometimes even three MLBs on them. The TV special, “The Violent World of Sam Huff,” brought the position into focus, but what a cast of characters. How about if I give you 10 names, each of whom was called, by some publication or rating service, the best ever at one time. Dick Butkus, Joe Schmidt, Ray Nitschke, Willie Lanier, Mike Singletary, Lee Roy Jordan, Tommy Nobis, Chuck Bednarik, and most recently, Ray Lewis and Brian Urlacher.

Believe me, each one had his supporters, and I can even throw in a couple more and make a case for them—Jack Lambert, the first MLB with really deep, downfield range, and Sam Mills, a personal favorite for his absolute genius on the field and ability to lift the performances of everyone around him.

OK, Dick Butkus is my No. 1, and I’ve spent many wee hours in press rooms and bar rooms waging the same battle over and over again. About 15 years ago, when run-stuffing middle backers started getting the hook on what were considered passing downs, I heard Butkus described as a player who would be on the field in base downs but not when it was time to throw the ball. That one has picked up momentum, and my only answer is to look at the people who are advancing it.

Butkus came up in 1965. That’s 42 years ago, as of this writing. In 1970 he suffered a serious knee injury that never was properly treated by the Bears and resulted in a six-figure settlement when Butkus sued them. He never was the same player after that, although, out of habit, they still put him on the All-Pro teams for two more seasons. So let’s say that his last good season was 1970, before he got hurt.

I look at some of the people who are issuing these pronouncements on what downs he would or would not play, and they weren’t born while he was in his prime. Or maybe some of them were in grade school, or teenagers. See what I’m getting at? They just don’t know nuttin’ about nuttin.’

Butkus had a reputation as some sort of Cro-Magnon who beat offensive linemen senseless and then did the same to ball carriers. “Not true,” said the Packers’ Jerry Kramer when I talked to him about Butkus. “The last thing he wanted to do was take you on. He tried to get rid of you as quickly as possible, so he could be in the best position to make the tackle. And when he was, yeah, the runners suffered.”

Sure, everyone knows he was hell on wheels against the run, but pass defense seems to be the point of contention. He didn’t have the range downfield of Lambert or Singletary. He wasn’t required to, because the Bears wouldn’t put him in zone coverage that would send him deep. He couldn’t close on a shallow receiver as Lewis could in his prime; Ray was the best I’ve ever seen at that. But Butkus didn’t get tied up in traffic, either, as Lewis occasionally would. He destroyed traffic; anything that would slow him down on his way to a tackle would infuriate him. The MLBs usual coverage responsibility in those days was second man out of the backfield, and speed usually wasn’t that big a factor because the assignment didn’t usually have him turning and running downfield with the back. By the time the second man out would turn upfield, the rush would have arrived.

Butkus covered the swing and flare routes, short stuff over the middle, and he knew angles and how to get through traffic and his coverage left nothing to be desired, even when he had to hustle downfield. He was fast enough. He had what Vince Lombardi called “competitive speed,” plus great instincts. But if I had to say what he did best, it was operate without a decent pair of tackles in front of him.

Lewis had a pair of 350-pound monsters, Tony Siragusa and Sam Adams, to keep the blockers off him in the ’01 Super Bowl. Urlacher played behind Tank Johnson and a very solid two-gapper, Ian Scott, and for most of the season, Pro Bowler Tommie Harris, in 2006, and a few years before that, Pro Bowler Ted Washington. Butkus’s tackles were nondescript guys such as Dick Evey and John Johnson and Willie Holman and Frank Cornish. He never played behind a Pro Bowl tackle in his entire career. And yet he could cut through whatever line scheme they had going against him in a flash, and get rid of the blockers and gather himself for the thundering hit. Yeah, I’ll stick with him.

* * *

ALL-TIME TEAM: CORNERBACK

They are legislating the cornerback position out of football. Interference rules get tighter every year, a push to produce more passing and scoring and offense that Tex Schramm and the Competition Committee started many years ago. The worst thing is that there’s no consistency to the calls. Basic things that coaches teach get flagged by one officiating crew, allowed by another. Players such as Champ Bailey, labeled a “shutdown corner,” still get beaten deep on occasion, when the Broncos are actually manning it up and not hiding in a Cover 2, everyone’s blue plate special these days. No, cornerbacks might have good streaks, or even a good run for a full season, but the following year they could come back and go into shock.

Here we go again ... all together now ... “It’s not the way it used to be!” OK, since my team dwells, depressingly, in the past perfect tense, let’s bring it as up to date much as I can. Deion Sanders. Timed in the high 4.2s. Greatest closing speed of any player, ever.

In 1994, when Sanders was 27 and presumably at the peak of his game, he had one season with the 49ers. I asked Merton Hanks, the free safety and a fellow with whom I was fond of discussing football and personnel and one thing and another, what he would write if he were doing a scouting report on his famous teammate.

“Don’t let him bait you into throwing the quick out against him. He’ll let two or three go and then take the next one back for six. It’s a cat-and-mouse game with him, and you’re not going to win. Don’t throw the deep sideline route on him. With the sideline for protection, he’ll either smother it or pick it off. You could try a deep post, just to keep him alert, but that’s risky, too, because it’ll look like a completion, and then he’ll close fast enough to get the pick.

“So what does that leave? You could try to run a pick play on him, but he’ll yell so loud that the officials will watch for it from then on and you won’t get it again. You could drag him across the middle on a shallow cross. He doesn’t like it inside much, but you’d better make sure your quarterback leads the guy just right, because if it’s a little bit off, a little bit behind him, Deion’s gonna grab it. If you complete a couple of those, you might force them to protect him in a zone, but anyone who coaches him has to know that’s the stupidest thing to do with him because he gets bored in zone coverage and loses a little concentration. But, if somehow you can manage to get them in some kind of a zone, well, it’s a big if. That’s how you get ready for Deion, the ‘if’ approach. Hasn’t worked too well so far, has it?”

Here is the problem with Jimmy Johnson, whom I will say without reservation is the greatest defensive back who ever lived: For the first eight years of his career, no one knew who he was. The 49ers weren’t in the postseason, they weren’t on national TV, he didn’t have big interception numbers (the only ones that define a cornerback) because everyone was afraid to throw at him. I was working in New York, as beat man covering the Jets for the Post, and the AFL didn’t face the NFL in the regular season in those days. I did have a friend, though, named Mike Hudson who’d been my classmate at Stanford and worked for the UPI in San Francisco during this period, a Niners fan, like me, and I’d get periodic letters from him saying, “You’ve got to see this cornerback we’ve got, J.J. Johnson. I’ve never seen anything like him.”

I remember seeing him once or twice during that period of 1961-68, his first eight years in the league, and I couldn’t record much of anything because he didn’t make any plays, and the reason for that was that no passes were thrown in his direction, or if there were, they amounted to maybe a couple of quick outs or something like that. That should have been the tipoff right there, but where’s the sign that says a former lineman had to be a keen evaluator of pass defenders?

Then the Niners got good with three straight playoff seasons, 1970-72. And a year or so before that, someone must have grabbed their PR director, George McFadden, by the throat and told him, “You’ve got to do something for J.J. He’s 31 years old and no one’s ever heard of him.” So in 1969, when Johnson already had passed his 31st birthday and had completed eight years in the league, the Niners’ press book listed an unusual statistic for him—passes thrown into his coverage, passes completed, yards gained. The numbers were 25 of 74 for 250. Broken down for his 13 games (he missed one) the average was 5.7 pass attempts (and there was no way of telling whether this was in man or zone coverage), 1.9 completions for 19.2 yards per game. Next year the press book did the same thing, and the two year stats came out to a per-game average of 5.9 attempts, 2.1 completions, 23.1 yards. I phoned my buddy, Mike. “Did he give up any TD’s?” I asked him.

“I never saw him give one up.”

Well, something must have kicked in because he made All-Pro for four straight years, starting in ’69, and led the defense on three straight division championship teams. By now I was watching him every chance I got, and I’d never seen anyone as smooth and graceful in his pass coverage. The Niners PR staff stopped listing those good stats after two years, but I saw games in which the opponent only threw at him two or three times. In ’71 he broke his wrist in the ninth contest and played the rest of the season with a cast on, and they still were afraid to test him, and when they did, he’d knock the ball down with his cast.

The fade started coming in ’73 when he banged up his knee, and for that season, and the following three, he slowly declined. But come on now ... those were his 13th through 16th years in the league, at age 35 through 38. I would talk to him by phone from time to time. A proud, dignified, humble person—a little sad, maybe, but able to hide his bitterness at being overlooked during the prime years of his career.

Then I became a Hall of Fame selector. Johnson’s name would surface briefly and then sink. I couldn’t understand it, but a decade and a half after his career ended he was still hardly known. I became strident, shrill, “You’ve got to understand that this guy...” etc. Wrong approach. After getting stiffed a few times, J.J. issued a statement that he would appreciate it if his name no longer would be proposed for enshrinement, just as Harry Carson did recently. Oh, my God. Something had to be done.

In 1994 my pitch was that this was J.J.’s last year as a “modern” candidate. After that he would go into a dismal swamp called the Seniors pool in which many were swallowed but few emerged. One per season, out of all the great, unrecognized names of history, would be pulled out of that groaning mass, that Dante’s vision of Hell, and presented for possible enshrinement. And that was the fate that would befall the greatest cornerback in history unless you, the selectors, acted and acted now.

Well, he made it. I saw him at the Pro Bowl in Hawaii. There was no more talk about how his name shouldn’t have been proposed, etc. He was in tears. I was in tears. End of story.

* * *

ALL-TIME TEAM: SAFETY

In the old days the strong safeties were sturdy fellows who were expected to lock on to tight ends, but still had to be gifted in zone coverage downfield. Free safeties were wispy guys with tremendous range. Then the monster safeties arrived, 220 to 230 pounds, strong or free, it didn’t matter. The big free safeties followed in the wake of the early “killer” types, Jack Tatum, Cliff Harris, the Chicago pair of Gary Fencik and Doug Plank. They were what Al Davis used to call “obstructionists,” a euphemism for roughnecks. The big strong safeties could either play “in the box,” as fourth linebackers in the base defense, or they could man the actual LB spot in nickel defenses.

At 6'3", 198, Ken Houston was a big strong safety in his era. You didn’t find many of them over 200 pounds. Even the Raiders’ intimidating pair of Tatum and SS George Atkinson weighed in at 200 and 180, respectively. The AFL knew all about Houston because he was the finest strong safety the league had ever produced, not just a big sticker, as most of them were, but a gifted cover man, too. But so what? AFL? AFC? It was all bush league to pro football’s old boys club. Even when Houston set a record for career interception TDs, which was broken by Rod Woodson 30 years later, nobody got very excited.

Then he was traded to George Allen’s Redskins. At 28 he wasn’t exactly a member of Allen’s Over the Hill Gang, but he finally got the exposure he needed to stake a reputation as the best ever at a position that is still not fully understood. I mean the 2006 AP All-Pro team didn’t even have a strong safety on it, preferring to go with two frees. Strong, free, what the hell’s the difference? Well, there is to me.

I’m still waiting for someone to come along and stake a claim at the position. Troy Polamalu looks promising, but he hadn’t done it long enough. Ed Reed has switched from strong to free. Nope, Ken Houston it is, until someone comes along to challenge him.

When I first started covering football, free safeties were what I call “range” types, players who patrolled vast patches of territory, basically small, wiry guys with tremendous ball instincts—Jimmy Patton, Yale Lary, One-Eyed Bobby Dillon, Willie Wood. Paul Krause, bigger and a bit slower, was the demon interceptor, but he wasn’t the tackler these other people were. It was hard to evaluate these players, at least it was for me, because we never knew what their responsibilities were on any play. So you let the interceptions do the work for you, if you were lazy, or you stacked up a whole pile of quotes, if you wanted to make it a popularity contest.

I lean toward Willie Wood as my range type because I just saw him as a more dynamic athlete, with an eye-catching burst to the ball, and a good measure of toughness. Emotionally, though, I’m drawn to Larry Wilson, who first popularized the safety blitz, a technique deemed insane at the time. So I’ve given him a designation termed “Combination,” since he was a terrific player in space, a fearless hitter and a safety whose techniques were near perfect.

But I can’t just neglect the dominant safetyman of our era, the Eagles’ Brian Dawkins, who does everything—blitzes, hits with real force, locks on to tight coverage downfield, and, here’s the thing that swings the election for him, seems to have an electric effect on everybody around him.

That brings us almost home, in this complicated category, but now it’s time to talk about hitters, because the free safety position appears in many guises, and it would be unfair to neglect the killer-type free safeties, because they can influence things in dramatic ways. Who was the greatest hitter who ever played—at any position? I’ve been asked that question on a million Mailbag columns for the Sports Illustrated website. In my Thinking Man’s Guide it was an easy one to answer because all I had to do was shut my eyes and I’d see Hardy Brown, an undersized, mean-spirited linebacker sending someone to dreamland.

They said he did it with a shoulder he could pop like a coiled spring. Some of the blows I saw him deliver looked more like forearm pops. The blow I remember best came when Brown’s 49ers played the Rams in Kezar Stadium and little Glenn Davis, Army’s famous Mister Outside, caught a swing pass and Brown popped him with the shoulder and he went down and stayed there. They took him out on a stretcher, and I had my binoculars on him and I can still see that deathly white face with the eyes closed. I thought he might be dead.

“Hardy Brown,” Y.A.Tittle once said, “had a shoulder that could numb a gorilla.”

I don’t know whether or not he could exist today. Technically a shoulder or forearm shot is not illegal, but too many of them aimed at the head would, I’m sure, generate some kind of legislation, Conduct Unbecoming, or Conduct Becoming Hazardous, or something like that.

The Colts’ middle linebacker, Mike Curtis, was nicknamed The Animal for obvious reasons, but I’d have to put him behind Brown in the mayhem sweepstakes ... except for one memorable shot I saw him deliver. In a 1971 playoff game against the Dolphins, a fan came out onto the Baltimore Memorial Stadium field just as Miami was about to run a play, grabbed the ball and started prancing around. Curtis’ blow, forearm to chest, sent him flying a good five yards.

I interviewed the fan in a police holding area after the game. He was still a bit drunk ... he’d taken a bus down from Rochester and had been drinking the whole way. He showed me his jacket. “Unzipped it, top to bottom,” he said. He seemed proud of it. Two weeks later he filed a lawsuit.

“Read and react. Everyone else just stood around, Curtis sprung like a panther,” Colt center Bill Curry said. “I felt like telling that fan, ‘That’s what I have to face in practice every day.’”

I don’t think the big guys generate enough speed to be considered the game’s most devastating hitters...OK, maybe the Broncos’ left defensive end, Richie “Tombstone” Jackson, who could split helmets with his head slap, might figure in there somewhere, but I think free safety has to rate as the player generating the biggest hits, replacing the linebackers.

Nowadays I’d give the nod to the Redskins’ free safety Sean Taylor, taking over from the Cowboys’ Roy Williams. But the all time No. 1, and I hate to go this route because I’m only reinforcing a negative, is Jack Tatum. The shot he delivered to Patriots wideout Darryl Stingley that paralyzed him was not, I believe, a clean blow, and I’ve argued this a million times. The pass was off target, Stingley was on his way to the ground when Tatum drilled him. He didn’t have to do it, but when someone has been trained in the guard dog mentality his whole career, don’t be surprised if he bites.

The first time I saw Tatum in the flesh was in the 1971 Rose Bowl, Stanford against Ohio State. The L.A. papers had been going with a pregame angle I thought was kind of silly—“Will Stanford dare to throw into Tatum’s territory?” I mean, you don’t just give up on an area of the field. Tatum played the open or wide-side cornerback in Woody Hayes’ defense. Right, and someone’s just going to avoid it. Silly, Southern California angle.

Stanford had a bunch of clever, pass catching backs, and on the game’s second series Jim Plunkett threw a five-yard swing pass to one of them, Jackie Brown, to the wide side. Uh oh. Tatum came up to meet him. It took 10 minutes to run the next play because an ambulance came out on the field to collect Jackie Brown and take him away. Right out there, red light flashing, while the Stanford guys stood around and watched. There were no more short passes into Tatum’s territory.

A footnote: I just looked at my play-by-play chart to make sure. Brown actually came back into the game and scored two touchdowns. But by running, not pass catching.

Were NFL players actually afraid of Tatum? Yes. Here’s a letter I received recently from his teammate, Todd Christensen, the All-Pro tight end:

“When I first came to the Raiders, I was a scrub, and as you well know, these are the guys who play offense for the defense, and vice-versa, on alternating days. So it was defensive day, and I was lined up in the slot to catch a slant. Plunkett timed it right, but so did Tatum, who had clearly lined me. He came in a blaze of color so fast that I actually shrieked a little aaahhhh, and then at the last second he veered off.

“He came over to me and said, ‘Don’t worry, young buck, I was just getting my timing down.’ I am not ashamed to tell you that fear made its way into my constitution.”

Tatum is not my all-timer. Cliff Harris is. His hitting was not quite on a par with Tatum’s—no one’s was—but Harris was a well-respected intimidator. Plus a fine cover guy. He started his NFL life as a cornerback. And I don’t think any player ever studied the science of hitting as he did.

The first time I ever got to know him, we had dinner at his restaurant in Arlington, Texas. We finally closed it at 2 a.m., and most of the time we had talked about an elaborate diagram he had drawn up, which I labeled “Cliff Harris and the Science of Hitting.” He had been an engineering major in college, and his chart was filled with notations such as “point of maximum impact.” It’s been awhile, but one thing I remember is his note on the swing pass, that the maximum impact does not come when the catch is first made. The idea is to wait until the back turns and starts upfield, then deliver your blow.

He used to hate the grades the coaches assigned. All it did, he said, was to induce a play-it-safe mentality. Don’t take chances, don’t screw up your grade. “I see a teammate in trouble, and I gamble,” he said. “I leave my assignment and cover for him, and I’ve guessed right and I knock the ball down. I grade a zero on the play. Same thing with a receiver coming across on a shallow route. I let him catch the ball and then I knock him out. Again, a zero on the play for allowing the completion. But the guy is out of the game.”

Harris has been up for the Hall of Fame a number of times. I’ve spoken on his behalf each time, but I’ve failed. He is now in the Senior pool. Pray for him.

* * *

ALL-TIME TEAM: SPECIALISTS

The last time I made up this list, Morten Andersen was my placekicker, based on all time numbers and percentage and whatever. But I’ve simplified it and zeroed in on one category. Clutch kicking. The greatest clutch kick I’ve ever seen was Adam Vinatieri’s 45-yarder in the howling snowstorm against Oakland that got the Patriots into overtime and subsequently into the Super Bowl, where his 48-yarder at the final whistle beat the Rams. Two years later his 41-yarder with four seconds left beat Carolina in the Super Bowl.

Thus he was three-for-three on the three most important kicks in the team’s history. A miss on any one of them could have affected the lives of many people. I don’t want to bog this down with a parade of numbers during Vinatieri’s whole career, but they are of Hall of Fame quality. Pressure kicking is the story. Just ask Mike Vanderjagt, who has the best lifetime percentage in history. When faced with the biggest pressure kick of his life, though, a 46-yarder that could have put the Colts into the AFC Championship Game, the result was a badly skunked low line drive, way wide right. The Colts got rid of him after the season.

Have you ever heard fans consistently cheer a punter and never boo him? Yes, if you’ve watched the Giants’ Jeff Feagles knock them out inside the five-yard line. Yes, if you were a 49ers fan in the late 1950s and 1960s when Tommy Davis was punting. Yes, emphatically yes, if you were sitting anywhere near me in the Kezar Stadium end zone, with the wind blowing in your face, watching Davis trying to get the Niners out of a hole ... “Come on, Tommy! Please, God, let him get one off!”... and hearing that sweet KABOOM! as he rockets another one into the gusts in the windiest stadium in the league. A high hanger into the wind, 48 yards from scrimmage, 4.8 on the stopwatch. Week after week of that, game after game.

Punting out of the end zone, into the wind, what’s the hang time? That’s one of many ways I judge punters, probably my favorite way. Davis was the best, and he’s my man. For years Sammy Baugh, with his phony gross average built on quick kicks, the old bounce-and-roll play, was the all-time career record-holder. Davis was second in gross yardage, punting in the worst conditions in football. Then Shane Lechler came along and forged to the lead with his 46.1 average. Nope Shane doesn’t do it for me. A middle-of-the-end-zone punter. Before they started calculating net yardage, it was a hidden statistic. Then finally bowing to the insistence of ex-Giants and Jets punter Dave Jennings, net started being counted, and the guys who couldn’t place the ball were exposed.

Lechler led the NFL by three yards on gross average in 2006, but he was 12th in net, which means that either, 1) he couldn’t keep the ball out of the end zone, which was true (19 touchbacks, high in the league and nearly double those of his nearest pursuer), or 2) the punt coverage team was crummy. But he’ll probably make the Hall of Fame some day if he keeps his gross up there. Ray Guy, a middle-of-the-end-zone punter with a lofty hang time, keeps coming up at the enshrinement meetings. Why, I don’t know. His career gross average is lower than that of anyone in the game today.

Glenn Dobbs of the old AAFC, with the top gross average ever, would be an exotic choice, but he really didn’t do it long enough, and I didn’t get to see him punt more than a couple of times in his career. Nope, it would take someone with an absolute thunderfoot to dislodge an emotional favorite such as Davis.

I’ll be really brief with the return men, since the numbers speak such a loud message. Right now Chicago’s Devin Hester is a one-year wonder. A few more seasons like his rookie year of 2006 and we’d have to take him seriously. Gale Sayers has the best career kick-return average in history. But it was a short career. Dante Hall has run a lot more kicks backs, but they’ve got the same number of TDs, and Sayers’ average is more than six yards higher. Sayers is my man.

Jack Christiansen, who doubled as the strong safety on the great Lions’ secondary nicknamed Chris’s Crew, burst onto the scene with a rookie and second-year season the likes of which never have been duplicated—punt return averages of 19.1 and 21.5 yards, with six touchdowns. He coasted in on those figures to give him the second-best career average in history. Well, I guess he’s my pick, even though Chicago’s great scatback, George McAfee, was three-hundredths of a yard higher. Hall was impressive for a while, but I’ve always liked him better returning kickoffs. So I guess that’s it, Christiansen over McAfee. Except for one man.

If I were down to my last punt return of the game, and I needed a single effort to get me back in position to win it ... that was it, one last shot ... who would I choose to be back there waiting for that kick? I can think of only one name, Deion Sanders. He might retreat and lose yards, and I’m sure that’s what brought his average down during his career. But that scene has been repeated just so many times, Sanders back there, kind of waving his hand from side to side, maybe clowning a bit, the crowd tense, expectant, the punt team nervous, and then, oh my God, he just might ... wait a minute, they’ve got him pinned. But those instincts of his, the excitement he generated...

His return average couldn’t match Christiansen’s. Career TDs were the same, six. But I just can’t get that picture out of my mind. I’m switching votes. Is it too late? Sanders is my all-time NFL punt returner.

If you wanted to break down the members of the special teams suicide squads into specific areas of expertise, as, say Buffalo coach Bobby April does, I’m sure you could give me a pretty efficient set of operatives, all going at a fully proficient level, pick one. But there’s a certain romance attached to this position, so for old times sake I’ll go with Henry Schmidt, one of the cast of unforgettable characters who decorated my Thinking Man’s Guide. I draw from it now.

I began covering the Jets full time in 1966. Schmidt was a reserve tackle. He was in his fourth pro camp, and by the time he hit New York he was just about playing out the string. His salary was $15,000. His face was craggy and lined, and it was painful to watch him getting out of the team bus after a 15-minute airport trip. His battered knees cramped and aching, he would hobble like a 60-year-old man.

When the Jets finally cut him, I was surprised to see that he was only 29. He looked like 40. And then I remembered who Henry Schmidt was. He was the greatest hot man, or wedge-buster, that I’d ever seen. I had watched him in his rookie year with the 49ers in 1959. He was inordinately fast coming down the field, for a guy 6’4”, 254 pounds. The Niners fans loved him, but when he’d hit the wedge and splinter it like kindling, it would draw a gasp, rather than a cheer, from the crowd. Usually the ball carrier would be part of the mob that Henry took down on his wild attacks. When people saw that he was actually able to get up and walk off the field, that’s when the cheers would come.

Seven years later I saw what all that wedge busting had done to Schmidt. The only miracle was how he had managed to survive as long as he did.

“The problem,” Jets linebacker Larry Grantham explained to me one day, “was that Henry was terribly near-sighted. He’d just aim at the biggest cluster he could find. Then someone fitted him with contact lenses. When he actually could see what was coming at him, well, that was it for Henry as a wedge-buster.

This ends the sad story of Henry Schmidt. And thus ends the roster of my all-time team.

Comments, thoughts or memories regarding Dr. Z? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.