The Kid Enters the Picture

Kevin Durant, looking like a 19-year-old who just got out of bed (which, at this moment, he is), ambles through the door of a Denver hotel and spots a half dozen autograph seekers armed with Sharpies. It is the morning of the rookie's first NBA shootaround, at the Pepsi Center some 10 hours before tip-off against the Nuggets. Durant scribbles his name on various collectibles, nods politely at a few comments ("I saw you play at Texas") and climbs slowly onto the Seattle SuperSonics' bus, at which point the hounds disperse. There is no beseeching of Nick Collison, no love for Chris Wilcox, no apparent eBay growth potential in Luke Ridnour.

And so it is for Kevin Durant, upon whom the spotlight will shine harshly this season, the Boy King of a faltering kingdom. The Sonics have no other marquee players, have gone 66-98 in the last two seasons and have their metaphorical bags packed for Oklahoma City, the team's ownership and the Emerald City having failed to reach a deal on a new arena. Moreover, with Portland Trail Blazers center Greg Oden out for the year after right knee surgery, Durant is the It rookie, the only first-year player on whom the league can focus its marketing muscle.

This amounts to a lot of attention for a teenager who's sharing a house with his mother, particularly since Durant's basketball trial will not be by fire but by conflagration. "Kevin is our focus," says coach P.J. Carlesimo, who was hired on July 5, one week after the Sonics made Durant the second pick (behind Oden) in the draft. "We can't hide that. We can't pretend he isn't. He will play 34 to 36 minutes and have a lot of rope."

This child-shall-lead-them approach is not new, of course, but Durant's task seems more burdensome than previous ones. Michael Jordan (1984-85) had three years of seasoning at North Carolina before he went to Chicago; Kevin Garnett ('95-96) could lean on mentors such as Sam Mitchell in Minnesota; Kobe Bryant ('96-97) had Shaquille O'Neal as a teammate in Los Angeles; and LeBron James (2003-04) arrived as the most physically imposing person in Cleveland (the Browns included). Remember, too, that Seattle said goodbye to two former All-Stars over the summer, when rookie general manager Sam Presti traded guard Ray Allen to the Boston Celtics and forward Rashard Lewis to the Orlando Magic. (The Sonics' coaches and brass share this grim-faced joke: We won 31 games last year and got rid of our two best players -- we've got to be better.)

Further, everything about the impossibly narrow-shouldered, 6' 9" Durant just says kid. The rookie Garnett was skinny, but he had (and still has) a granite toughness. Durant is a waif. He cops to 220 pounds, five more than he weighed at the predraft camp, but he looks as if he could be blown over by a stiff Northwest breeze, not to mention any future winds that might sweep through the Oklahoma plains.

Still, there is plenty of substance to Durant -- in his person (laid-back but tough), his marketing portfolio (about $80 million in deals with Nike, EA Sports and Gatorade) and his game (smooth, smart, versatile). That was clear in the opening days of a pro career that promises to be electric, no matter where the Sonics ultimately call home.

GAME 1: OCT. 31, AT DENVER NUGGETS

Durant commits a rookie mistake upon entering the Pepsi Center, carrying his backpack past a security guard at the players' entrance. "Let me look at that, son," he says to Durant, who complies.

During warmups Durant paces himself, the combination of mile-high elevation and opening-game nerves leaving him gasping. Carlesimo pulls him aside before the tip-off. "Good luck and just go out there and have a good time," the coach says. "Don't worry about anything else." As Durant stands outside the center circle -- Carlesimo had penciled him in as his starting shooting guard seconds after becoming coach -- his eye is drawn to the signature shoes worn by Nuggets forward Carmelo Anthony. "They the new ones?" Durant asks Melo, who says yes. Durant is tempted to ask if Anthony will autograph the sneakers for him afterward. "But I kind of stopped myself right in the middle, because I've got an NBA jersey on too," Durant explains later.

The game goes predictably, which is to say that Durant looks like a 19-year-old among men and the Sonics are gallant but outgunned, getting blown away down the stretch in a 120-103 loss. Durant shoots an airball from 10 feet, fails to finish near the basket several times and misses an opportunity to exploit a nine-inch advantage when Allen Iverson switches off on him. He begins aiming his shots and even hopping up and down in an effort to will them into the basket.

But Durant has his moments, too. He goes coast to coast for a layup, cleverly using 6' 9" rookie teammate Jeff Green as a screen when he gets in the lane. (Carlesimo wants Seattle to be an up-tempo team, having hired Mr. Transition, Paul Westhead, as his top assistant, and both can envision Durant taking off with a rebound on a one-man break or sprinting downcourt to finish off a long pass.) On one occasion Durant overplays Anthony to his left and effortlessly blocks Melo's jumper. It's unlikely that Durant will ever be a lockdown defender -- players so long have trouble getting into that cobra-strike position -- but Carlesimo will play a lot of scramble zone, trying to force tempo by creating turnovers and by making opponents take quick shots, a seemingly ideal defense for the long-armed Durant (he has a 7' 4 3/4" wingspan), who finishes with three steals.

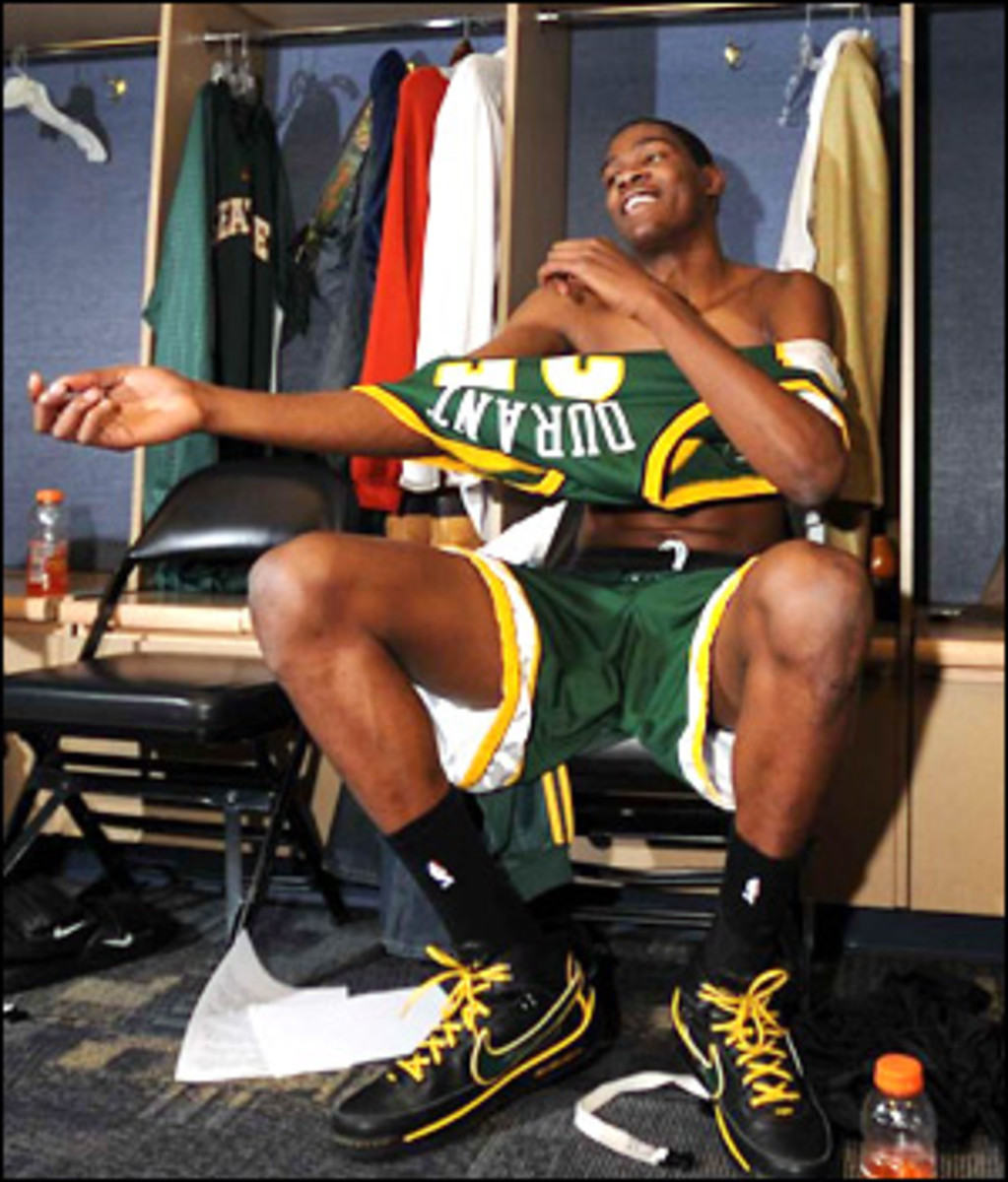

After the game, Durant sits at his locker staring at a box score that, steals aside, reads like a mediocre transcript from his one year at Texas: 18 points (on 7-of-22 shooting), five rebounds, one assist, one block. Durant will no doubt lead the known world in 7-of-22s this season; he is a perimeter shooter who won't get many easy baskets and a rookie who won't get many officials' calls. He showers and returns to find a crowd of reporters surrounding his locker, forcing him to execute that trickiest of maneuvers -- wriggling into boxer shorts while still wearing a towel. No other Sonic is of interest to the fourth estate, and there is a real danger that all the oxygen will be sucked out of the area immediately in front of Durant's locker. "KD," Wilcox shouts at his swarmed teammate in a good-natured but mocking tone, "I seeeee you!"

Many a team has been ruined by a vastly uneven distribution of publicity, particularly when the object is so callow; some Bulls deeply resented the notoriety surrounding Jordan, who was practically Lord of the NBA before he played his first game. Fellow rookie Green, the fifth pick, out of Georgetown, says it's no problem for him -- "Kevin and I are both just trying to get by, learn the game, find ourselves as pros" -- but Collison, the starting center and longest tenured Sonic at four seasons, acknowledges the potential for jealousy.

"Sure, guys notice it," he says. "But I don't sense anyone is worried about it. Kevin doesn't seem bothered by the attention, and in some way he's embraced it without being arrogant. But everything is so new here that we're all just trying to find our way. Including Kevin."

Durant's responses are blander than broth, but how much perspective can one expect from a teenager after one NBA game? I just told myself to go out and have fun. I was nervous but the butterflies went away. I learned a lot. There's 81 more games to go, and we're going to get better.

His parents, Wanda and Wayne Pratt, are waiting for him back in the arena. (Wanda Durant gave birth to Kevin before she married Wayne, so the son was a Durant; she changed her name after they tied the knot.) "You played great, baby," says Wanda as her son reaches down to hug her.

Wanda made the decision to live with Kevin this season, but her son was all for it. "She can make me a better person and make the transition easier," he says, "so why not?" It's a one-year deal, up for renewal after this season, but Durant says, "I'm probably going to sign her back up." Wanda, who will travel to several of Kevin's road games this season, says she won't stay if she's not wanted in the comfortable house they rent on a Mercer Island cul-de-sac. "A mother knows when to back off," she says. (Wayne will remain at the family home in Suitland, Md., to support their son Tony Durant, a junior forward at Towson State.)

But doesn't the arrangement hinder Kevin's, uh, social life? "He respects me enough that he does not bring anyone home," Wanda says. When her questioner raises an eyebrow, she quickly adds, "I'm not saying he doesn't meet women -- he's in the NBA, he's young and he's handsome, right? I'm just saying he doesn't bring them home." Kevin later confirms this.

GAME 2: NOV. 1, VS. PHOENIX SUNS

Durant crosses paths with Suns guard Steve Nash before the game at Key Arena. The two-time MVP nods at him and says, "Hey, Kevin," leaving the young man stupefied. "I couldn't believe he knew my name," Durant confides later. Phoenix assistant coach Alvin Gentry is taken aback by his first brush with Durant. "I just saw your two guard and he's taller than anybody we got," Gentry tells Westhead, "so I think we're going home."

Durant's height is striking; last week Wanda suddenly looked at him and said, "Son, you are tall." He always was among the tallest boys his age, yet, fortunately for him, no coach forced him to become a center, allowing him to concentrate on shooting, ball handling and finding seams. Durant is most often compared with Houston Rockets swingman Tracy McGrady, but he's not in T-Mac's league as a pure athlete. "The first player I really followed as a kid was Vince Carter," says Durant, "which is funny because he jumps out of the gym and I can't jump at all."

Carlesimo grabs Durant during warmups once again, and he makes this night's message more specific: "I want you to be aggressive and shoot the ball." Wearing his yellow-and-green home Nikes, Durant receives the honor of being the last starter announced. (Durant's agent, Aaron Goodwin, expects that the Swooshers -- who signed Durant to a six-year deal worth more than $50 million -- will have a Durant shoe and apparel line by next year.)

Against an elite team, albeit one without a strong defense, Durant looks comfortable. He makes Westhead's night by going end-to-end on a break one minute into the game. Then he delivers a slick pass to Collison for a hoop, gets a dunk in transition and hits a step-back jumper on Raja Bell, the Suns' down-and-dirty defender. "Kevin is really good," Bell will say later, "and really big."

In the second period, the crowd of 17,072 begins chanting "Save our SON-ics," directed at principal owner Clay Bennett, who is sitting in a luxury box with longtime Mercer Island resident (and former Seattle coach) Bill Russell. While Durant pays little attention to the ugly civic squabble, to fans he has a special role in it -- after waiting so long for a marketable young star, they don't want to lose him (and the team) after a year. However, Bennett insists that it is impossible to turn a profit in what he considers an outdated facility, and city leaders insist they will not finance a new one.

In an interview the next day Bennett bristles at the notion that current Sonics such as Durant and future free agents might not want to play in cowboy country. "You're coming at it from the perspective that Oklahoma City is necessarily an inferior market," he says, calling the question a "hypothetical some-may-say." Well, one "some" might be Goodwin. The agent wouldn't comment on the probable change of venue for his main man, but his history is to look for megadeals in major markets, of which OKC is not one.

Durant is the best player on the court for much of the game, but down the stretch Phoenix puts extra pressure on him. He coughs up the ball on a double team and commits a charging foul, and the Suns come from behind to win 106-99.

The rookie will need to get stronger to hold position in the post, so he can catch the ball close to the basket and get to the line more often. Plus, the Sonics are still sorting out who will be getting him the ball among a point-guard trio of Ridnour, Earl Watson and Delonte West. As Carlesimo says, "We have to find out who we're going to start, who we're going to use as a backup and who we're going to screw."

Still, Durant's line in the box score looks better than it did the night before (a game-high 27 points on 11-of-23 shooting), though the locker-room scene is exactly the same. I'm not thinking about Rookie of the Year or anything like that. I'm just trying to come out and help the team. There's 80 games to go, and we're going to get better.

It's unclear when the games-to-go calculations will begin to get foggy, but it will probably be soon.

GAME 3: NOV. 4, AT LOS ANGELES CLIPPERS

The best time to see that Durant is still a kid is before games. At Staples Center this morning he shoots for only 15 minutes, then plants himself on the scorer's table to check out the peripheral action, specifically the warmup routines of the Clippers' dance team. It's not what you think -- well, it's sort of what you think -- but Durant gets just as big a kick out of watching the junior team, swaying and bobbing his head to replicate the preteens' moves. He is already celebrated around Seattle for offering to play video games with any young neighbors who have the temerity to come knocking on his door. "Sometimes they bring him cookies," says his mother.

On his way to the locker room, Durant stops and signs items for fans: a sneaker, a photo, a ticket stub. "My, I hope that young man gets fed more," a woman in the crowd says. It's not as if Durant is trying to be a beanpole. Wanda, who prepares most of his meals, met with the team's nutritionist two days ago, and she briefed her son before he headed to L.A. "I'm supposed to eat the same stuff, only more of it," Durant said last Saturday at the team's hotel in Marina del Rey. "Four eggs instead of two. Four pieces of baked chicken instead of two. Four meals instead of three. But it's going to be lifting weights and just normal growth that will really put the weight on."

Durant looks like a man in this game. He sticks his head into the action and finishes with eight rebounds; through his first three games he was averaging 6.0, suggesting that someday he could get double figures by relying on his long arms and instincts. Offensively, he seems comfortable from the 12:30 p.m. tip-off, draining threes (he will hit three of six), sticking quick-release jumpers from the wing and, most promising for his potential superstardom, putting the ball on the floor and pulling up from midrange. On one play in the first quarter he hits a fall-back jumper despite being closely guarded by Clippers stopper Quinton Ross -- a shot that signals bad news for future Sonics opponents.

But this is bad news for the Sonics: L.A. outscores them 37-25 in the fourth quarter to pull away with a 115-101 victory. In the final 12 minutes of their three losses, Seattle has now been outscored 98-64. Durant, having played his best all-around game (24 points on 10-of-19 shooting, eight rebounds, five assists, only one turnover), is asked afterward if he feels burdened because his teammates rely on him too much. "I don't think they rely on me too much," Durant says immediately. "We're a team." His response might be programmed, but at least he's been programmed well. He takes responsibility for not getting out and defending the three-point shot (the Clippers hit seven), promises that he and his fellow Sonics will amp up the effort in the fourth quarter and, well, here it comes....

"We'll get better," says Durant. "We have 79 games to go."

And so the countdown continues. Durant's future seems limitless, but lots of long nights and hard times await the Boy King before he truly belongs among NBA royalty.