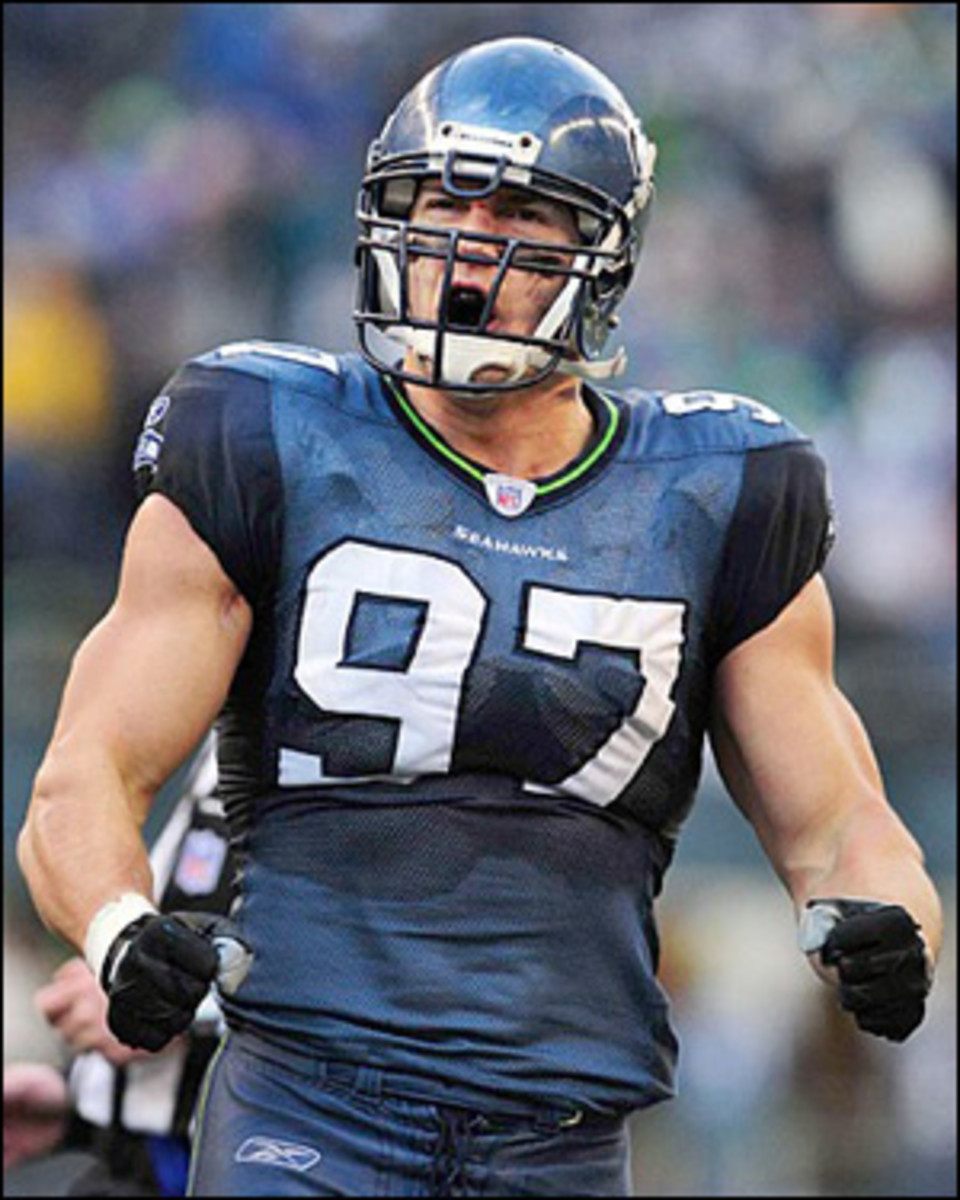

Full Blast

In the moments before kickoff, some players listen to metal and some listen to rap. Some talk to God and some talk to themselves.

Seattle Seahawks defensive end Patrick Kerney wraps a black graphite glove around his neck, wires it to the portable neuromuscular stimulator in his locker and sends small currents of electricity into his body. He literally energizes himself. "It fires you up -- your adrenal glands," Kerney says. He also freaks out some of his less tech-oriented teammates, who eye Kerney skeptically, as though he might be part man and part machine.

When Kerney goes home to his house in Bellevue, Wash., he climbs into a hyperbaric chamber to infuse his body with oxygen. Then he falls asleep under silver-threaded "earthing" sheets plugged into an electrical outlet, thus ostensibly neutralizing free radicals, those highly reactive particles that can damage cells. "I know this is going to make me sound ridiculous," says Kerney.

That might be true if he were not making so many others look ridiculous on the field. In his ninth NFL season Kerney, 31, led the NFC with 14 1/2 sacks, and in the wild-card playoff game at Qwest Field last Saturday the visiting Washington Redskins assigned two and sometimes three men to keep him out of their quarterback's face. It was no use. With his adrenal glands firing and no free radicals disrupting him, Kerney was a force, amassing seven tackles and four quarterback pressures in the Seahawks' 35-14 victory. This weekend he travels to Green Bay to face Brett Favre and the Packers in the divisional playoffs. The neuromuscular stimulator will be making the trip.

Kerney had a large role in wrecking the NFL's most inspiring plotline. The Redskins were playing for Sean Taylor, their teammate who was slain in late November. They were playing behind Todd Collins, a quarterback who until December had not started an NFL game in a decade. Washington, which had won four straight simply to reach the playoffs, took a one-point lead in the fourth quarter and, after recovering a kickoff that the Seahawks' return team somehow failed to touch, had third down at the Seattle 12-yard line with 11:44 left, and a chance to put the game away.

Washington positioned right tackle Stephon Heyer and fullback Mike Sellers across from Kerney, 604 pounds of pass protection. The Seahawks' end split them as if they were straw men and swiped at Collins's right hand, forcing an incomplete pass and a field goal attempt. Shaun Suisham's 30-yarder hooked left, and the Redskins lost their juju. Seattle scored three straight touchdowns -- two on interception returns -- to put an end to Washington's march. "You hurt more because you know the cause was bigger than this game," said Redskins wide receiver Santana Moss afterward, invoking Taylor's memory.

Kerney skipped off the field with blood on the bridge of his nose, cuts along both arms and eye black smeared across his cheeks. Turns out he didn't hurt his nose on any of the Redskins' double- and triple-teams but on a pregame head butt with fellow Seahawks outside the locker room. "It felt good," he said, poking at the fresh scab.

A first-round pick of the Falcons in 1999, Kerney had been a fixture on the defensive front in Atlanta, starting 105 consecutive games before tearing his right pectoral muscle in November 2006. He missed the final seven games of the '06 season but was nevertheless highly sought when the free-agent signing period opened in March. Kerney visited Denver and was expecting to sign with the Broncos, but he humored the Seahawks and took a flight to Seattle aboard owner Paul Allen's private plane. Jim Mora, who'd coached Kerney in Atlanta and is now an assistant with the Seahawks, went along for the ride. As the plane neared the Pacific Northwest, Mora asked Kerney a weighted question: "So, do you want to see Mount Saint Helens?"

He didn't need to wait for the answer. Mora ducked his head into the cockpit, the pilot called air traffic control for clearance, and the plane dipped its wing. For a volcanic defensive end, it was the ultimate joyride. "You could see the steam rising," Kerney says. "You could see the mountain blown out on one side and the trees all matted down. The sun was breaking through the clouds. An artist could not have painted it any better."

The Seahawks had an unfair advantage in their free-agent courtship. From his time with the Falcons, Mora knew that Kerney was a licensed pilot with his own four-seat Beechcraft, so the next day in Seattle, Kerney got a ride on Allen's seaplane, which landed in the middle of Puget Sound. Then he was taken to Allen's private hangar in Everett, Wash., which is stocked with vintage World War II fighter planes. Says Seattle linebacker Lofa Tatupu of his bosses, "They knew exactly what they were doing." On March 5 Kerney agreed to a six-year, $39.5 million contract with the Seahawks.

It was his first recruiting trip of any kind. Kerney, who grew up in Newtown, Pa., attended The Taft School in Watertown, Conn., which produces plenty of National Merit finalists but not so many edge pass rushers. He went to Virginia to play lacrosse and walked on to the football team. Somehow, a prep-school grad and history major whose favorite sports included lacrosse, hockey and wrestling became a first-round NFL draft pick.

Kerney is still exotic for his breed. In a league of Cadillac Escalades, he drives a Honda Accord hybrid. He regularly goes to sleep by 9:30 p.m. He hikes on off days -- his favorite spot in the Seattle area is Tiger Mountain because he can't get to the top without vomiting at least once. "I've been there with him," Seahawks defensive end Darryl Tapp says. "It's not a lot of fun."

But there's a reason why Tapp keeps following Kerney into weight rooms and up mountain peaks, even if the experience is usually painful and nauseating. Last season, without Kerney, Tapp had three sacks and 22 solo tackles. This season, with Kerney serving as his mentor and bookend, Tapp racked up seven sacks and 41 solo tackles.

After Saturday's playoff victory a few of Kerney's defensive teammates peered into his locker, checking out the graphite gloves and the muscle stimulator, as though the gadgets held some scientific secret to his dominance. "At first we all thought it was a little weird," tackle Rocky Bernard said. "Now it's almost normal."

And it's more than enough to fire up the Seahawks' adrenal glands for a deeper postseason run.