Global Warning

Osi Umenyiora fell asleep every night beneath a white blanket adorned with little one-eyed men. He'd pull the cover under his chin and stare at the faces, pondering who they were and where they came from. They had patches over their right eyes and two swords crossed behind their heads. They wore silver helmets with a black stripe down the center. Umenyiora wondered why they needed the helmets.

The blanket was a gift from his stepmother, Ijeoma, who'd picked it up on a trip to the U.S. and took it home to Lagos, Nigeria. Young Osi loved the blanket, even if its decorative origins eluded him. "I just thought it looked cool," he says.

Only after he had turned 14 and moved to the States did he make sense of those one-eyed men. Watching television on a Sunday afternoon at his new home in Auburn, Ala., Umenyiora stopped on a channel showing athletes running into each other. Two teams were playing American football. One was wearing silver-and-black helmets, with those same little men on the sides -- patches over their right eyes, swords crossed behind their heads. "I finally realized then who they were," Umenyiora says. "The Oakland Raiders."

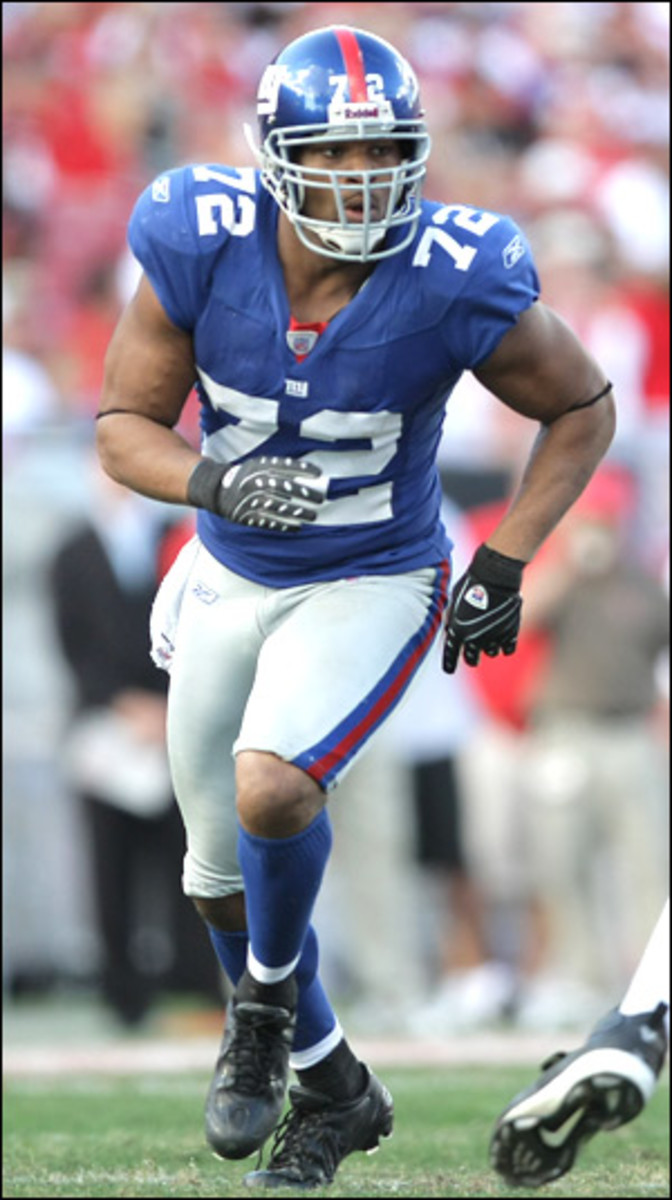

It was the beginning of an accelerated Western education. Born in London and raised in Nigeria, he will play in the most American of games on Sunday and could have a decisive role. The 26-year-old defensive end, who had 13 of the Giants' league-leading 53 sacks this season, is a key factor in the critical matchup of Super Bowl XLII: the Giants' pass rush against the Patriots' pass protection.

Umenyiora is an ideal representative of New York, a mash-up of cultures. Ask him where he comes from, and he hesitates. His passport says the United Kingdom. His family is from Nigeria. His pass-rush skills are from the Deep South. His accent has hints of cockney, Igbo and Southern drawl. "I feel like I come from everywhere," says Umenyiora, who now splits time between Atlanta and Edgewater, N.J. "But I've taken something different from all the places I've lived. I try to represent all of them to the fullest."

He is royalty from New York to Nigeria. Umenyiora's father, John, a retired telecommunications contractor, is a king in the village of Ogbunike, which makes Osi a reluctant prince. Last off-season, when Umenyiora returned to Nigeria for the first time since he left as a teen, the villagers made him an honorary chief -- not for his football achievements, but because of the 30 scholarships he endows each year for local schoolchildren. "It was a huge party," says Umenyiora's older brother Ejimofor. "There was a lot of music and dancing. It was very unusual for someone so young to be a chief."

Umenyiora earned his second Pro Bowl nod this season and made almost $6 million. But his gridiron success is largely an accident. He grew up in England playing soccer. When he was seven his family moved to Nigeria, and he played more soccer. But his father believed his children could get a better education in the U.S., so Osi traveled to Auburn, to live with Ejimofor and his older sister Nkem, who was attending nearby Tuskegee University.

Osi had no urge to play football, but in Alabama, a 14-year-old who weighs almost 250 pounds does not have much choice. He went out for the team when he was 15 and a junior at Auburn High. "The first day, I remember everybody was on the field for practice -- except Osi," says Clay McCall, then the school's defensive line coach. "I went to the locker room and saw him standing there with his pads next to him. He didn't know how to put them on."

He learned quickly and played extensively that year. But early in his senior season Umenyiora quit. Ejimofor and Nkem had pulled their brother off the team, believing football was the cause of his slipping grades. Osi spent two weeks pleading before they begrudgingly let him return. "The way we were brought up, sports was not a form of employment," Ejimofor says. "It was a form of recreation. I was totally against letting him play football. But in hindsight I guess it was a good decision."

Having drawn no interest from recruiters, Umenyiora was planning to enroll at Auburn. But when he saw Tracy Rocker, a scout from then Division I-AA Troy, in the hallway at his school, he introduced himself. "I am going to play for you," Umenyiora said. Rocker, a former All-America defensive lineman at Auburn, was too startled to laugh. He watched tape of Umenyiora and came away nonplussed. Umenyiora did not get to the quarterback. He did not make tackles. But he also never stopped chasing the ballcarrier, never stopped running. "If he was willing to do that," Rocker says, "I was willing to give him a chance."

Umenyiora red-shirted as a 16-year-old freshman at Troy, then shuttled between tackle and end for the next two seasons. Coaches remember the day he found his groove: Oct. 19, 2002, the eighth game of his senior year. Troy was playing at Marshall, and Umenyiora was lined up across from Steve Sciullo, a future NFL draft pick who hadn't given up a sack in two years. The week leading up to the game, Troy defensive ends coach Mike Pelton taunted Umenyiora: "No sacks in two years."

In the second quarter Umenyiora sprinted around Sciullo and tackled quarterback Byron Leftwich. As Umenyiora ran to the sideline, he howled, "I got him! I got him!" By the end of the season, Umenyiora had a school-record 16 sacks and was an NFL prospect. "That game changed everything," Pelton says. "It was the moment he took off."

Back in Nigeria, no one understood. Umenyiora's mother, Chinelo Chukwueke, had never seen him play. His father had come to Troy to watch a game, but it was so cold he never got out of his car. His large family was just learning the word sack.

Though Umenyiora was not invited to the NFL combine in 2003, Giants G.M. Ernie Accorsi drafted him in the second round. A year later, when Accorsi was negotiating the famous draft-day trade with the Chargers for quarterback Eli Manning, San Diego asked that Umenyiora be included in the package. Accorsi refused. "It would have been a deal-breaker," Accorsi says. "There was no way I was going to trade Umenyiora."

In Umenyiora, New York found a book-end for Michael Strahan, as well as a soulmate. Like Umenyiora, Strahan was raised overseas, in Germany. And like Umenyiora, Strahan played college football in relative obscurity, at Texas Southern. "The more we talked," Umenyiora says, "the more we realized we are almost the same person."

With Strahan rushing from the left and Umenyiora from the right, opponents have not known whom to double-team. In Week 4 this season the Eagles assigned primary responsibility for Umenyiora to 6' 6" left tackle Winston Justice, who was making his second start, in place of injured veteran William Thomas. Watching on television, Thomas was concerned. "When you're going up against Osi, he lines up really wide, about three or four feet away from you," Thomas says. "He gets down low in that sprinter's stance and takes a running start. If you don't get off the ball fast -- really fast -- he's already around you."

That night, Umenyiora was the next coming of Lawrence Taylor. He raced around Justice for one sack, then another, and another. The Eagles tried chipping him with a running back. They slid their protection toward him. But he kept finding quarterback Donovan McNabb. The 6' 3", 261-pound Umenyiora got so tired from sacking McNabb that he needed an IV before halftime.

On the way to the locker room for the treatment, he saw Taylor standing on the sideline. The two had never met. Umenyiora nodded. Taylor nodded back. "It was an amazing moment," Umenyiora says. "It was like I had his spirit inside of me." He finished the night with six sacks, one short of the NFL record.

If there is a game that can inspire hope in the Giants this week, and fear in the Patriots, it is that one. But whatever happens on Sunday, Umenyiora will have another game to play. He is going to the Pro Bowl, and his parents are coming along. His mother saw him play for the first time in October, when the Giants faced the Dolphins in London. His father will be watching too -- assuming, of course, it's not too cold in Hawaii.

After that, Umenyiora plans to return to Lagos and to Ogbunike. He will be greeted as a prince and a chief, but he is not comfortable with those titles. He prefers to be known simply as a Brit, an African and a Southerner, the havoc wreaker who comes at you from everywhere.