Cut from the Same Cloth

To understand why Georgetown coach John Thompson III regards basketball the way he does -- as an accretion of details and small remediations -- it's worth revisiting a February night in Providence in 1988. Back then Thompson served as Princeton's senior co-captain, and the Tigers led Brown by two points with seconds to play. As he prepared to inbound under his own basket, Thompson began to experience what he calls "the loneliest feeling in basketball."

The referee had begun his five-second count. Teammates couldn't seem to shake themselves open. No timeouts remained. Finally, Thompson threw a pass down the floor.

"I could see the ball slide like a curveball as it came out of John's hand," remembers a teammate, Bob Scrabis, who watched helplessly from downcourt. (Scrabis says that Thompson had a bum hand with two taped fingers, but today the man who threw the pass won't even hint at an alibi.) A Brown player picked off the pass 50 feet away and heaved up a shot to beat the buzzer. From beneath the basket Thompson watched as the ball traced a path through the net, almost precisely to the spot where he stood.

This is the act in his basketball life that Thompson most wishes he could have back, when one of the best passing forwards in Princeton history failed at the skill he had made his own. It would be one of only 39 turnovers Thompson committed all season, against 103 assists. But as a result the Tigers suffered their third consecutive one-point loss in Ivy League play and second straight at the buzzer, relegating them to a third-place finish in the conference. Thompson's class of 1988 became the first Princeton team since 1959 not to play in a postseason tournament.

"Who told you about that?" Thompson says two decades later, sitting in the Georgetown basketball office. "That's never been written before."

He rises from his chair and makes his way to a window, where he inspects the bracken behind McDonough Arena. For a moment he's quiet, a captain again, feeling the weight of leadership. Then he turns. "I let the team down, the coach down, the program down," he says. "It still hurts. It's one of the things that drives me."

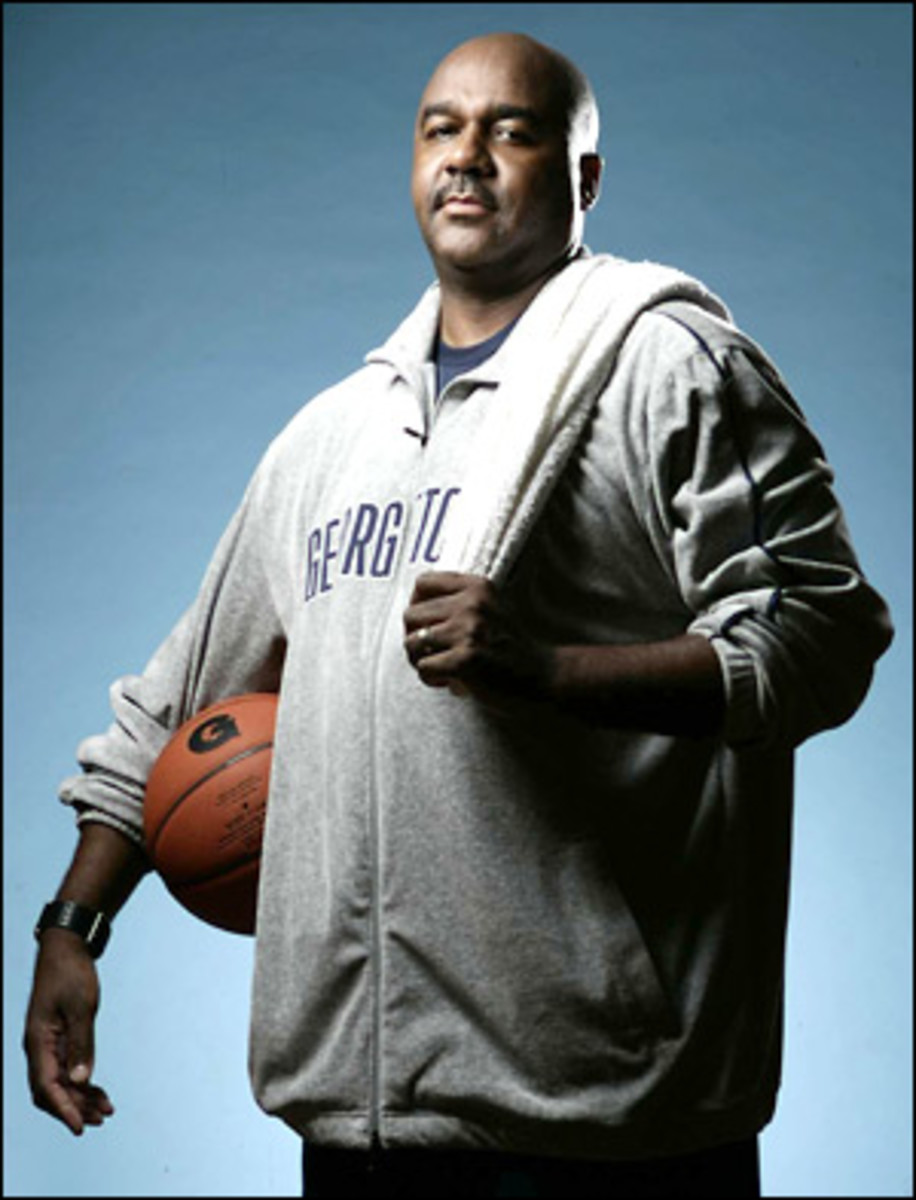

As he finishes his fourth season at Georgetown, fire and fastidiousness in equal measure have helped Thompson, 42, resurrect the program his father once built into an unlikely basketball power. Big John Thompson's eldest son guided the Hoyas to the NCAA Final Four last spring and to a repeat first-place finish in the Big East Conference this season (the latter a feat his father never accomplished). For next season John III has commitments from four of Rivals.com's top 100 high school recruits, including No. 1 Greg Monroe, a 6' 10" forward from Hayden, La., who chose Georgetown over Duke without even visiting Durham. And over the past two seasons the Hoyas have proved to be masters of both the comeback and the close game. A year ago they wiped out deficits in three straight NCAA tournament victories, including a defeat of Vanderbilt on forward Jeff Green's buzzer-beater, and an even more memorable 11-point recovery against North Carolina in regulation before winning in OT. This season the Hoyas made up six points in the final 3 1/2 minutes to beat Connecticut when 7' 2" center Roy Hibbert sank only the second three-pointer of his career; and they made up five points in the last 2 1/2 minutes to win at West Virginia. In all, they were 6-0 in games decided by three points or fewer in the regular season. In a tournament game that comes down to the short strokes, Georgetown might be the last team any title aspirant wants to face.

Thompson's attention to detail could be seen right from the season's first moments, when the freshman fans at Georgetown's Midnight Madness preseason practice made a mess of the "We are . . . Georgetown" chant that again resonates at home games. Thompson shook his head. "Fix it, Jon," he said, handing a wireless microphone to Jonathan Wallace, his senior point guard, so Wallace might lead the benighted first years through Cheering 101. Signs reading FIX IT, JON have appeared at Hoyas games ever since. "He lets you know every day that this is a game of inches, not feet," says guard Jessie Sapp. "You have to take it an inch at a time."

This isn't merely how Thompson's players learn in practice. It's how they've come to think in games. Consider that comeback win against West Virginia in late January. The Hoyas edged into the lead on Sapp's three-pointer in the final seconds, but during Georgetown's last defensive stand, Patrick Ewing Jr. failed to warn teammate Jeremiah Rivers of a screen, which opened a path to the basket for the Mountaineers ball handler. Fix it, Pat. Ewing desperately scampered over to block what would have been a game-winning layup. Later he told the press that all he could think of was atoning for his mistake.

"We don't get rattled," says Thompson, who attributes much of his endgame serenity to the teachings of his old coach at Princeton, Pete Carril. "I've been taught that that's what the game is, the situation before you. Our job is to teach. Their job is to figure it out, together. If we're going through that process, there's no time to get worried.

"That's how I operate. Good, bad, I don't know. But we must slowly, methodically prepare for the next opponent, the next possession. You understand what your goal is -- to win a national championship. Then you forget about it. Let's get better today. You can get lost if you wander."

It's a waste of time to ask Thompson why he's so dialed into the moment. "You are who you are," he says. "There's too much work to be done to go through self-analysis. You guys [in the press] can figure me out. I don't need to figure myself out."

But he'll talk expansively of his influences. "Pops, Coach, my mom, Marv," he says. "I hope you see a little of all of them when you see me."

A brief cast of characters: Pops is Georgetown's Hall of Fame patriarch, who was as devoted to the grand gesture as his son is to the tiny increment. Coach is Carril, another Hall of Famer and the fussbudget for whom John III played and later apprenticed at Princeton and of whom he says, "There aren't too many days I don't hear his voice in my head." Mom is Gwen Thompson, whom friends and family agree young John most takes after. (Gwen and John Jr. were divorced in 1999.) And Marv is Marvin Bressler, a world-weary sociology professor, now retired, and longtime faculty adviser to the Princeton basketball team. Which is to say, John III is two parts Thompson and two parts Tiger.

That probably accounts for why he's so different from his famous father. Pops never would have asked an end-of-the-bencher as they walked off at halftime what he thinks the team might do differently, or let a reportorial nostril anywhere near the scented candle that today burns in the office of the Georgetown coach. "John weighs things," says his father. "When he says, 'Uh-huh,' it means he's heard you, not that he agrees with you. When I say, 'Uh-huh,' I got my mind made up."

"He got along with everybody," remembers Carril, which couldn't have been said of him or Pops. "He gets along with officials too." (Some people think that this helps account for his teams' success in close games.)

As a hoops pedagogue, John III is most like Carril. The father's teams were primarily about defense played offensively; the son's are -- and Carril's were -- more about offense played defensively. When he arrived at Georgetown, John III knocked down a couple of walls in the basketball office to create a common space where coaches could swap ideas, as the staff did at Princeton.

Consider too one of the favorite maxims of the old Princeton coach, a riposte Carril delivered whenever someone suggested that students working toward an Ivy League degree couldn't also play basketball at an elite level: "Nothing is more important than what you're doing when you're doing it." It gets John III's approach precisely.

It would be a mistake to regard his twin influences as somehow debilitating. "Every second-level Freudian is trying to stick him with a double Oedipus for being the son of one Hall of Fame coach and playing for another," says Bressler. "I don't think that's troubled him for more than 30 seconds. He looked at both of them as resources. He accepted what he wanted and discarded the rest.

"John wants to win basketball games but not to 'vanquish the foe.' He wants to confirm that his analytical observations are correct. His intelligence is not a strategic intelligence. He believes in tactics, both within a game and over the course of a season. You win Friday. You win Saturday. If there are enough Fridays and Saturdays, lo and behold, you win the championship."

If this habitation of each moment leads to an obliviousness of the big picture, John III pleads guilty. He even says as much, remarking in early February, "We'll pick our heads up at the end of the Big East season and see where we are." Keep your head down, and any difficulty can be managed, even the diagnosis of breast cancer that John III's wife, Monica, then 38, received in November 2005, convulsing their lives for a year.

John Thompson Jr. was off on a road trip as a reserve center with the Boston Celtics on the day in 1966 that his first child was born. It was his wife's birthday, March 11, and Gwen drove herself to the hospital.

The Thompsons raised their children the same way the first John Robert Thompson raised John Jr. "I was trained what to want," Big John says of his own upbringing. "My father couldn't spell John Thompson, and we lived in public housing in almost every part of the District [of Columbia], yet I considered myself privileged -- safe and fed and taught."

John III was introduced to the discipline of parochial school and eventually Gonzaga College High, a Jesuit school in the heart of the District. Gonzaga made enough of an impression that returning there to recruit a player a few years ago, John III could recite the Lord's Prayer in Latin when he ran into an old classics teacher. Teammate Byron (Snoop) Harper remembers his friend as athletically limited and smart enough to compensate: "John was a landlubber but very efficient below the rim."

With Thompson calling defensive signals in a morphing zone and directing the offense as a 6' 3 1/2" forward, the Eagles went 24-6 his junior season, beating DeMatha Catholic and its star Danny Ferry one night as Pops' friend Dean Smith looked on. "That game epitomized why John is such a good coach," remembers Dick Myers, who was then Gonzaga's coach. "We were up six to eight points in the fourth with no shot clock and thought we'd work some clock in a spread offense. But during a timeout John said, 'We're doing so well, let's stay with what we're doing.' And we did. I got a very nice letter from Dean Smith afterward, and he said he was especially impressed that we kept running our stuff with the lead and didn't change tactics."

The one time Carril scouted him, Thompson regularly broke the press with a single pass. "He saw the floor," Carril recalls. Just the same, during Thompson's campus visit Carril spent most of an hour's conversation laying out his shortcomings. "He says if I don't do this and this and this, I'd play jayvee," John III recalls. "Part of me was wondering if he really wanted me to come. He reminded me a lot of my dad. One's a little white guy and one's a big black guy, but the pride, the caring, the commitment to their institutions -- they're very similar."

Was it really his choice to go to Princeton?

"That's a good question," John III says. "I think so. I know my mom wanted me to go, but my dad, he's more, 'We'll let you make your own decisions till you make a wrong one.' "

"He talks as if he made the decision," says his father. "But I can tell you this: If I didn't want him to go, he wouldn't have gone."

For his first two seasons John III underwent Carril's hazing in practice. "If you were any good, your father would have taken you" was among the milder gibes. "Shut up," Pops told his son when he complained to him. "I'm dealing with other people's kids."

"I hated Coach Carril, and I love him to death right now," John III says. "Everyone who's played for him goes through the same thing. You make those calls home. And then you grow up."

Upon graduation Thompson entered a dealer-training program with Ford. No one in the family even pretended it was his decision. "He needed to go into the world of work and see what it's about," Big John says. A few years later he edged his way back toward basketball, joining a sports-marketing firm near Philadelphia. But the high fives around a boardroom table after closing a deal rang hollow next to the real thing, and he jumped when Carril called in 1995 to say he had an opening for a volunteer assistant.

Seven years out of school, John III no longer had to fend off his father, beyond a barb that a Politics degree from Princeton seemed like an awfully pricey thing to be wasted on a profession like coaching. For that first season he kept his day job, driving from his office in Cherry Hill, N.J., to practices during a season capped by the Tigers' upset of UCLA in Carril's final NCAA tournament. Two years later, with Thompson a full assistant under Carril's successor, Bill Carmody, the Tigers went 27-2, finishing the regular season ranked No. 8.

But in 2000 things came a cropper. In short order Chris Young, the team's 6' 10" All-Ivy center but also a dominating righthanded pitcher, signed a $1.5 million contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates, which in the Ivies made him ineligible to play any sport. A few weeks before fall practice, Carmody lit out to become the coach at Northwestern. Spooked, Spencer Gloger, who had been recruited by UCLA before signing with the Tigers, suddenly decided to transfer and play for the Bruins. Princeton athletic director Gary Walters named Thompson to replace Carmody -- but three more would-be regulars wound up unavailable, one because of injury, another for academic reasons and a third after he quit the team.

Thompson gathered the survivors in a conference room and insisted that all the pieces to win an Ivy title sat around the table. "He never let on for a minute that playing for anything less was acceptable," remembers Nate Walton, the 6' 7" senior who would be pressed into playing center. In their opener at Duke the Tigers suffered a 37-point, nationally televised humiliation, the school's worst loss in more than 90 years. In practice the team ran numbing hours of drills on offense, and another player ended up quitting. "Success has a price, and that year we all paid it," recalls Ed Persia, a freshman on that team.

Yet along the way Princeton stole a December tournament at Ball State, beat Xavier and its star forward David West, and won six of its first seven league games. Later in the season, on the bus home after back-to-back 17-point losses at Columbia and Cornell, Thompson let a silent hour pass, then got up in the aisle to address his men. Recalls Walton, "Instead of beating us into the ground, it was, 'O.K., how do we get better?' And, 'We're still in first place in the league.' "

The Tigers stayed there, thanks to an alchemy of freshman energy and senior urgency. Of their 16 wins, seven came by single-digit margins. "A lot of it was just getting us to believe that we had a chance," says Kyle Wente, whose off-balance 25-footer won a game at Harvard. "When you went over to the bench, whether you were up a point or down a point, he was such a calming presence. Just, 'Guys, we've been here before. This is what we do.' You see that throughout his career, and it goes back to his demeanor and how it instills confidence."

After beating Penn to clinch the Ivy title, Thompson met the press alongside Walton, who had just put into the books a stat line that is emblematic of the Thompson approach -- a quadruple single of nine points, eight rebounds, seven assists and six steals. "Guess the cupboard wasn't as bare as people thought," said the coach.

His first team had won a berth in the NCAAs by launching more three-pointers than twos, by attempting the fewest free throws of any Division I team and by failing to throw down a single dunk -- offense played defensively, indeed. "He's the best game coach I've ever seen," says Walters, a former coach himself and past chair of the NCAA basketball committee. "He's passionate about his players but completely objective in how he manages the game. He's a great example of emotional intelligence."

By the end of his four-season run at Princeton, Thompson's teams would win with better rebounding, quicker shots and more isolation plays than the program's hidebound devotees were used to. Some fans weren't quite sure what to make of these stylistic apostasies, grumbling that Princeton no longer delivered as many of the signature backdoor baskets that they could frame and hang in the great rooms of their orange-and-black minds. But John III had begun to recruit athletes he believed would flourish with more autonomy and at a stepped-up pace, foreshadowing what he would create at Georgetown. A mind is a fine thing to deploy, but athletic ability is a terrible thing to waste.

Meanwhile, Thompson had his eye on something loftier. "One day I said to him, 'You're too competitive to want to stay at this level, aren't you?' " recalls Sonny Vaccaro, the shoe-company impresario and longtime Thompson family friend. "He said, 'Yes, Mr. Vaccaro. I want to go for the brass ring.' Obviously he couldn't do it at an Ivy League school. Once he got into coaching, the competitive Thompson blood took over."

In 2004 an opportunity arose at Georgetown, from which his father had abruptly retired in midseason five years earlier. The Hoyas had just lost their final nine games to finish 13-15, their worst record in more than three decades, and Pops' successor, Craig Esherick, was on his way out.

There would be the small matter of being a Thompson at Georgetown. But he has proved to be an adept curator of tradition. "I want those two trees there to shade me," John III told an interviewer in New Jersey earlier this season, referring to Coach and Pops. "I'll hide in the shadows."

Thompson's old boss at Princeton, Walters, likes to share with his coaches a copy of Walt Whitman's Song of Myself. When he does, he highlights this stanza:

I am the teacher of athletes,

He that by me spreads a wider breast than? my own proves the width of my own,

He most honors my style who learns under? it to destroy the teacher.

"People who are mentors understand those lines," Walters says. "You don't want replicates. You want originals. We're the sum total of the major influences in our life, but John is also his own man.

"By the way, one of the next lines is, 'My words itch at your ears till you understand them.' "

Princeton and Georgetown are braided through Thompson's life, and it was at the expense of one and for the other that he had already scored his greatest recruiting coup. When John III was a Princeton freshman, his resident adviser asked him to host a high school senior from New Jersey -- a young woman who was leaning toward Georgetown, believing Princeton to be too close to home. He showed her around campus, and she enrolled. "There wasn't even much of a conversation," Monica Moore Thompson recalls of the first time they met. "It boiled down to, 'Go to Princeton.' " By his senior year they were an item.

In May 1997 they were married in the chapel on campus. During her husband's days as a coach at Princeton, Monica worked in the university's development office, but with their move to D.C. she stopped working briefly while he guided the Hoyas to the NIT his first season.

Monica's diagnosis with breast cancer came during a routine physical on the eve of the 2005-06 season. The next few weeks were a blur of emotions, obligations and uncertainty for the whole family. But she was there for the season opener at Navy on Nov. 18, having driven to Annapolis with the three Thompson children: daughter Morgan, now 10, and sons, John Wallace, 6, and Matthew, 4. The following week she prepared Thanksgiving dinner for the team -- just as she'd done every year since John had become a head coach -- even though she was booked for surgery the next day. (The players didn't learn of her diagnosis until several days later.) "John and I had talked about him taking a leave," Monica says. "His dad mentioned it too. In the end we decided against it."

Her chemotherapy ran concurrently with the basketball season, from December to March. The night before a home loss to Vanderbilt, John III slept at the hospital in a recliner at her bedside. Says Monica, "Looking back, he says that was the least prepared he'd ever been for any game as a player or coach."

Her husband never missed a session of chemo all season, even as the Hoyas knocked off No. 1 Duke in January and reached the Sweet 16. "He would go to the doctor's office, to practice, back to the doctor's," says Ronny, John III's younger brother. "But John has an incredible ability to handle a lot of things and keep it all together. He's like our mom. He's very gathered."

Monica, whose mother died of lung cancer, says she's now "cancer-free." She consults for her alma mater and is the executive director of the John Thompson III Foundation, whose beneficiaries include the Capital Breast Care Center. "Looking back, I don't know how we got through it," she says. "Well, I do know -- we were given a support system of family, friends and neighbors."

The run to the Final Four last spring served as a Thompson family catharsis. For John III and Monica, says Ronny, "it was really the first time there was nothing major they were dealing with." The emotions rattling inside Big John, whose own father had died before Georgetown reached its three NCAA title games in four years during the early 1980s, left him speechless during the overtime win against North Carolina, even though Westwood One was paying him to do the game as a radio analyst.

As often as not, Big John, 66, may be found on winter afternoons in McDonough Arena. His son leaves a chair out for him. The father is usually in sweats, sometimes shrouded by a hoodie; and he's usually silent, a condition he so rarely submitted to during his coaching career. If he has any piece to say, he has unburdened himself of much of it earlier in the afternoon as cohost of his sports radio talk show.

"You notice," he says, in reference to his son, "he coaches without a whistle?" Big John had used three whistles -- different tones to signal different messages.

Simply by hanging around he can do himself a great pleasure, which he calls "meddling." This does not entail pelting his boy with X's and O's. A few weeks ago John III told Pops that he was headed off to watch a recruit. "You need to get home and get some rest," came the reply. "And there's reports of black ice out there."

John III went to the game anyway. "He's wrapped up in basketball, and I enjoy fussing," Big John says. "That's why I meddle. Now, he just has to keep from seeing me as seeing him as my little boy."

From his seat in McDonough, the elder Thompson sometimes reaches for the clipboard and pen that John III has hung on the wall beside the chair, so he might make a note to share. Sometimes he nods off to sleep. If he were to look up to his right, he could see where, during a game in his third season, in 1975, someone unfurled a bedsheet emblazoned with THOMPSON, THE N----- FLOP, MUST GO.

Growing up, John III saw his father bring home from the office a bag of hate mail every few months. "Wackos," as John III calls them, phoned and sometimes showed up at the family home. A sportswriter in Utah called his father "the Idi Amin of college basketball," while opposing fans greeted one of his dad's players, Patrick Ewing, with banana peels and signs alleging that he couldn't read. "For every positive John Thompson story there was a negative one," his son recalls. Given all that, what son, if he were to hold the same position at the same school as his father did, wouldn't burrow himself into each moment?

John III is not apolitical -- his senior thesis was on Black Separatists and Nationalists in the 1980s -- and one day he may be ready to pick a battle or two, but where exactly is the advantage now? Especially when there's a pass out there, waiting to be properly thrown.

Of course, all the father's trailblazing made the son's blinkered focus possible. You can get lost if you wander -- and Papa was a rolling stone, wading into issue after issue in a way his own father never could, for the first John Thompson had been yanked from school as a child to work the fields of southern Maryland. John Jr. pinned green ribbons on his players' uniforms in 1981 to raise awareness of the Atlanta child murders; he walked off the court in '89 to signal the injustice he saw in the NCAA's Proposition 42; and a year later he met with Rayful Edmonds III, the most notorious drug dealer in D.C., to tell him to stay away from his players. "I don't feel I was ever in a position where I could just be a basketball coach," he says. "If I were in a meeting or in public, I felt an obligation to speak up. People criticize Michael Jordan for not doing more in the public sphere. But Bill Russell and Jim Brown did what they did so Michael Jordan wouldn't have to."

For one generation, three different tones of whistle; for the next, no need for a whistle at all. Or if you prefer an alternative metaphor, listen to Bill Shapland, Georgetown basketball's longtime sports information official. "Like a lighthouse," he says of the father. "He focused on a whole realm of things. Now I work for a man who's a laser beam."

A year after John III arrived at Georgetown, the school hired a new athletic director. The coach could be forgiven for taking it personally. Bernard Muir had played for the Brown team that beat Princeton with that halfcourt shot in 1988.

When he arrived in D.C., Muir innocently asked Thompson if he had played in that game.

"I don't recall," Thompson replied, deadpan.

Not until two years later, when together they went to Brown for Thompson to collect the Black Coaches Association's Fritz Pollard Male Coach of the Year Award, did the Georgetown coach share with his boss his central role that night.

"John," Muir told him, "you're only as good as your last game."

Of course that's the way administrators see it, and fans and media and alumni. But there's an itch at the ears of a coach who knows better. Who knows that you're only as good as your next possession.