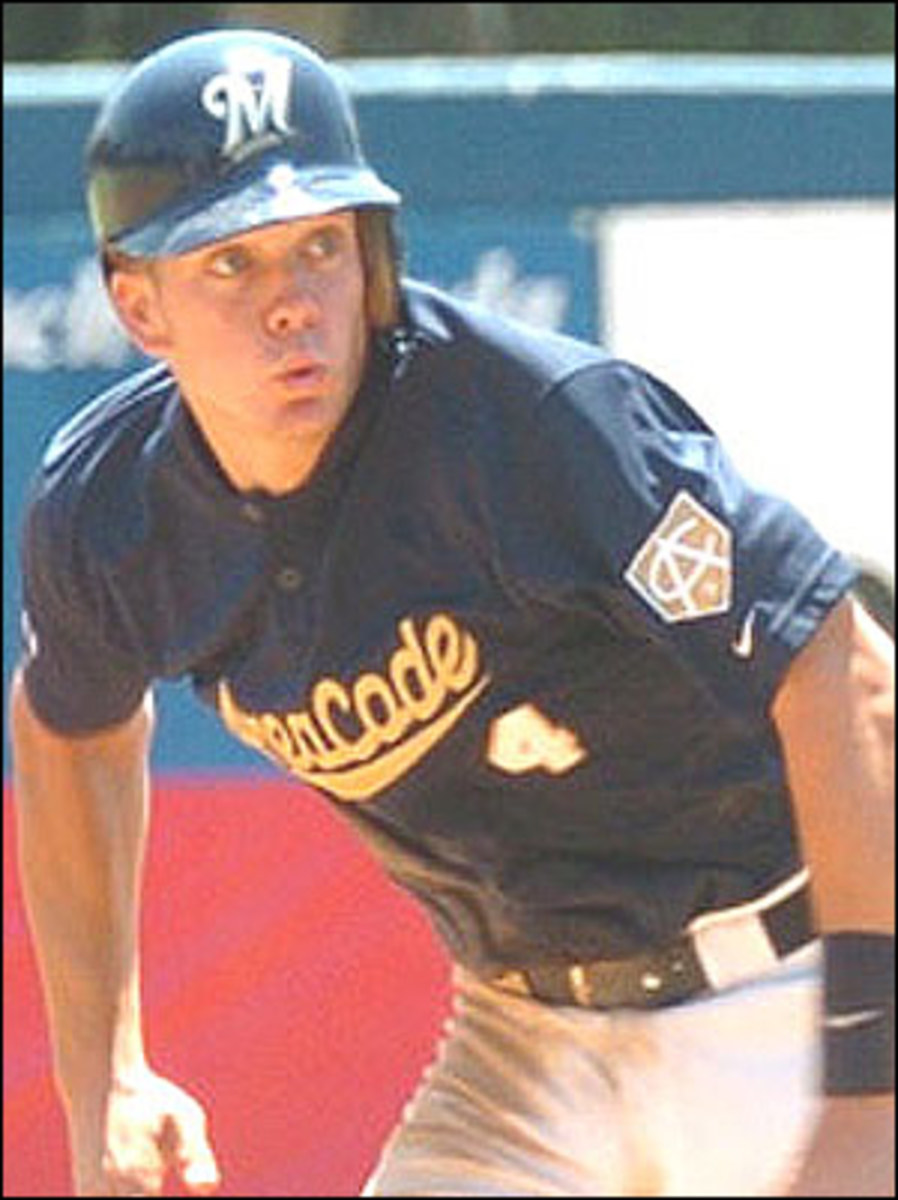

Cutter Dykstra following father's baseball path at Westlake High

Lenny Dykstra's kid loves the tag. He embraces it as if it were a style more than a birthright.

Cutter Dykstra, 18, loves the fact that DYKSTRA is stitched above a No. 4 on the back of his Westlake (Calif.) High jersey. His left hand is covered with blisters from hours spent in the batting cage, and his pants are cut up and speckled with blood stains from sliding aggressively into second base, all in homage to his famously frenetic father.

"You see that," says Cutter, pointing at his blood-stained pants. "I love that. I love it. I love always having my uniform dirty because that's how my dad did it. I kind of want to bring that style back to baseball -- a hard-nosed approach, a real blue-collar type. I throw my body around and do whatever it takes to win."

Cutter routinely references his famous father, who played with the New York Mets and Philadelphia Phillies from 1985-1996 and made it to a World Series with each club. Lenny Dykstra isn't so much a shadow as he is an outline of the player Cutter, a 5-foot-11, 175-pound center fielder, wants to become.

"I want people saying that's Lenny's son," says Cutter, taking off his cap and rubbing his matted brown mane. "I want people saying, 'He looks just like his dad. He's plays just like his dad. He approaches the game just like his dad.'"

Cutter, a speedy sparkplug who is batting .491 through 16 games this season, is projected to be a first- to third-round pick in MLB's amateur draft this June. Cutter already has shown more potential coming out of high school than his father did when he was selected by the Mets in the 13th round of the 1981 draft.

"Cutter has a lot more physical traits and power than I ever had," says Lenny, who also adds that he hit .550 and didn't strike out during his senior year. "Cutter's got better athletic skills than I had. He's been blessed."

While Cutter's baseball baptism came at an early age -- "From the time he was old enough to sit up, he wanted a ball," says his mother, Terri -- his father tried to steer him away from the game.

"The fact that Cutter plays baseball is not the most important thing to me," Lenny says. "I wanted him to do what he wanted to do and he came to the game on his own."

It was, at times, frustrating for Cutter's mother who knew her son wanted to play baseball. She had to prod her husband into helping their middle child learn the game.

"I think Lenny stood back too much. I would tell him, 'Go tell him to do this or that,' and Lenny would say, 'No, just leave him alone, let him have fun and play,'" says Terri, whose eldest son, Gavin, 26, played baseball at Cal State Northridge and youngest son, Luke, 11, is a switch-hitting seventh grader. "He's very relaxed out there about the whole thing. I'm the one in the stands going crazy."

Lenny initially signed Cutter up for golf, a sport that came fairly easily to him as he hit 260-yard drives and posted a 5.1 on his handicap sheet to his father's 10.8. "He wanted me to be a professional golfer because we lived on the Sherwood Country Club," Cutter says. "That's what he really wanted."

Cutter left his golf clubs in the closet after the eighth grade. Even so, Lenny was hesitant to be that overbearing father figure in the stands during ball games. Lenny didn't want the spotlight on himself.

"You'll never find my dad at a game," Cutter says. "No one will ever find him."

Cutter points to a car next to an oak tree nestled on a hill high above the baseball diamond, barely visible from his seat in the dugout.

"He's usually up there in his Maybach and I'm sure he has about three laptops lined up in front of him," he says, referencing his father's constant tracking of the stock market, which is a part of his second career as a successful businessman. Lenny is also launching a magazine for professional athletes, The Players Club. "But he always watches the games and he really watches them closely. I'll go into his office after games and we'll go over the counts; we'll go over all the mental stuff. He preaches that I should always play the game off the scoreboard. Being in the game and being a smart player."

Cutter has a scholarship offer from UCLA but says he'll likely go pro if he is drafted in the early rounds. He doesn't display any pretense as to his priorities in life.

"Everything I do is baseball," says Cutter. "Everything I do, I ask myself, 'How is thing going to help my game? How is this going to get me to the next level? How is this going to show everyone that I'm going to be a star?' Everything I do is all out."

Said Westlake High coach Zach Miller: "I haven't seen a kid who takes it as serious as he does. He wants to be the best and obviously a lot has to do with his last name but he's his own player. He's going to make a name for himself."

While Cutter would like to make his own mark in the majors, he envisions that will come as a result of playing the game with same reckless abandon that hasn't been seen since his father was scrapping with catchers and stealing bases.

"When I get on the field, I want to put on a show for people. I want people to pay to come watch me play," Cutter says. "I want to entertain people every time I'm on the field -- lay out for balls, run through walls, whatever it takes. That came from my dad."