Bolt's performance freezes time

Here then was a change in the course of sprinting history. Records fall, and then they fall again. But never in recent history has a 100-meter record record fallen like it fell on Saturday night in China.

If you are reading these words, you will watch NBC this evening in the United States. You will, in all likelihood, see Michael Phelps win his record-breaking eighth gold medal, completing a remarkable week at the Water Cube. You will also watch the final of the men's 100 meters and see something that stretches believability, one of those deliciously rare moments in sport when performance is so transcendent that it freezes time.

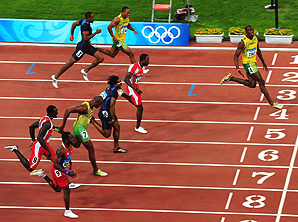

Bolt -- 21 years old, tall (6-foot-5) and slender by sprint standards, apparently immune to the pressure that might have slowed his ascension and, no small matter, Jamaican to his marrow -- won the gold medal in the Olympic 100 meters with a time of 9.69 seconds. He broke his own world record by .03 seconds and won by a full two-tenths of a second over Richard Thompson of Trinidad and Tobago, the widest margin of victory since Carl Lewis won by the same margin over countryman Sam Graddy in 1984 (Walter Dix of the USA was a surprising third in a personal best of 9.91 seconds). "[Bolt] is a phenomenal athlete,'' said Thompson. "It was a matter of time until he produced what he is producing now.''

Yet it was not just the time. And it was not just the margin. It was the manner in which Bolt did it, shutting down with at least 15 meters left in the race and celebrating in a sort of arrogant exuberance as he crossed the line (and then running another 100 meters around the turn, much like he did in New York on May 31, when he first broke the record). He did something that seems nearly impossible: Shattering the world record while leaving the impression that he could have done much more.

"That's not important,'' Bolt said outside the stadium, long after the race. "I came here to win a gold medal.''

Soon will come the inevitable innuendo about whether Bolt is free of banned performance-enhancing substances. Surely they have started somewhere already. Such is the nature of track and field and sprinting in particular. "I pray that everybody is above board [clean],'' said four-time Olympic medalist and current NBC sprint analyst Ato Boldon. "Because this kid is like something we've never seen before. We're seeing the future right here.''

The Olympics were just Bolt's eighth 100-meter final, and he has dropped from 10.03 last summer to 9.69. Lord knows what he might run in the 200 here on Wednesday night, or what he might do to the U.S. on the anchor leg of the 4x100-meter relay Friday night.

But for now, the sport embraces an epic moment. There had been a buzz in the air since the Games opened, growing more urgent as the 100 final approached. On Friday night, before Ethiopian distance runner Tirunesh Dibaba's Olympic record 10,000-meter win (and American Shalane Flanagan's bronze medal run), Bolt ran 9.92 in the quarterfinals while jogging the last 50 meters of the race.

In the press tribune above the track, 1996 Olympic gold medalist Donovan Bailey (a native of Jamaica who is doing sprint analysis for the Canadian Broadcasting Company and also knows Bolt well), walked over to Boldon and simply let his mouth hang agape. "I know,'' said Boldon to Bailey. "The easiest 9.92 we've ever seen.''

Tyson Gay, the double world champion who had entered 2008 as the Olympic favorite only to be ambushed by Bolt, had struggled through his first two rounds after suffering a hamstring injury in the 200 meters at the U.S. Trials on July 5 and missing four weeks of training. On Saturday afternoon, former British Olympic sprinter Darren Campbell said, "The guy who could pressure Bolt is Tyson. But the Tyson who's here isn't really Tyson.''

Those words proved prophetic when Gay failed to make the final, finishing fifth in his semi early Saturday evening. Gay, a class act in every regard, stood for interviews after his exit. He voice cracked as he told a group of writers, "I gave it my best, I just didn't come through. I talked to my mother [Saturday] and she mentioned I seemed a little bit down. Maybe it was because I just didn't have that 'pop,' you know what I mean, like at USAs. I feel like I let them down a little bit.''

Gay disappeared quietly through a doorway, a painful example of the capriciousness of the Games. Timing is everything and the Olympics show no mercy.

The heptathlon finished, and Hyleas Fountain of the U.S. hung for a desperate third by running a gutty personal best in the 800 meters. All of the heptathletes ran a lap together, and then sprinters entered near the 100-meter start. A scoreboard video montage focused on Bolt and countryman Asafa Powell, who was hoping to expunge the memory of a disappointing fifth in the '04 Games and a silver medal behind Gay at last year's worlds.

Music filled the stadium and Bolt rocked with it. He pointed to the country name on his yellow singlet. He made a grand gesture, pulling his hands apart as if preparing to shoot an arrow into the night sky. "I've been doing that all season,'' said Bolt. He answers inquisitors playfully, a big kid who was on the European circuit at age 17 and desperately homesick for his home in the Caribbean. (Six of the eight starters in the final were from the Caribbean, more than in any previous Olympic final).

At the gun, Bolt started with the pack, and he was no better than fourth at 30 meters. But his transition from a low drive to a full sprint was breathtaking. In five strides he was in the lead and in 10, he was gone. The stadium seemed to gasp.

In the aftermath, beaten rivals were peppered with questions asking them to predict what Bolt might have run and what he might run on some future day when he does not choose to celebrate early. (Thompson, for one, suggested 9.54). This is typical. Often track spoils a moment with statistical analysis or drug innuendo. There is place for both, and there is place to embrace magic, if only for a moment.