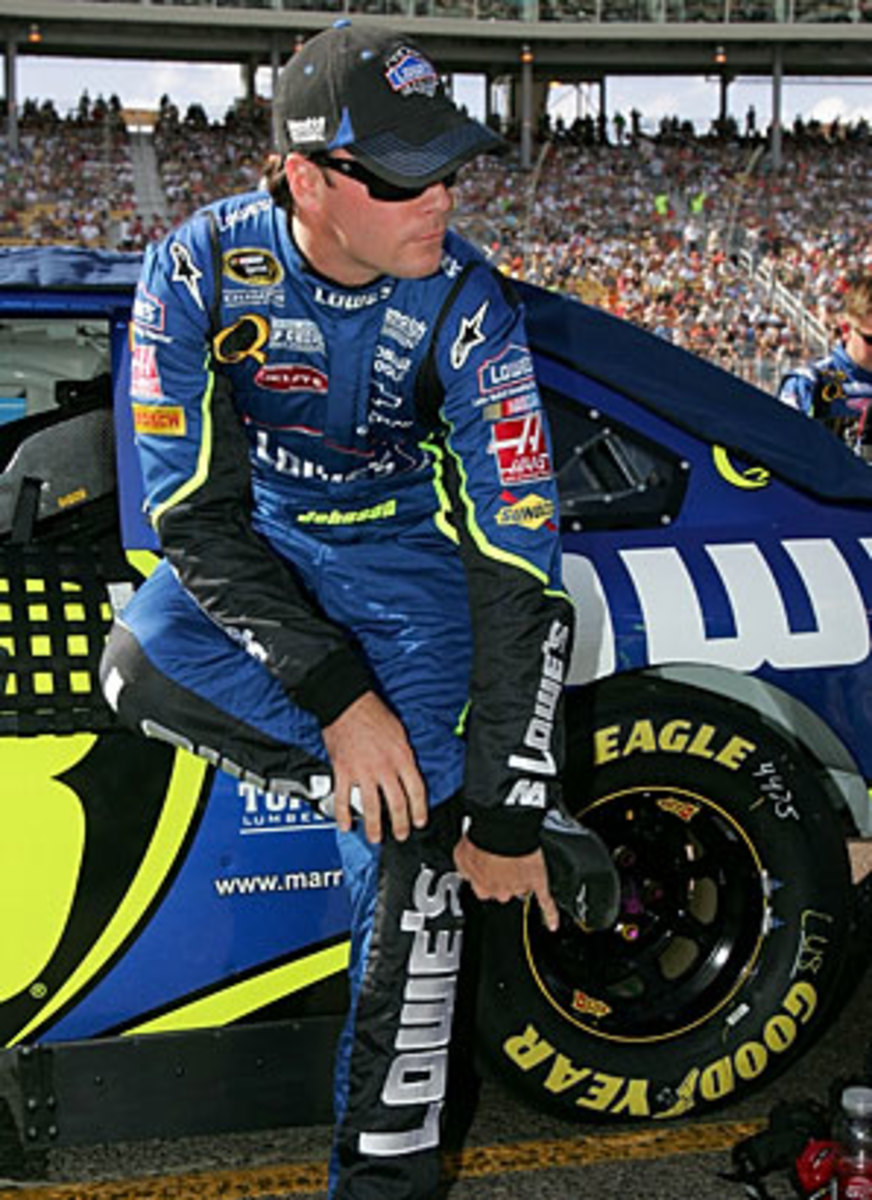

Don't let looks deceive you: Jimmie Johnson is a dangerous man

But Jimmie Johnson didn't box like the old driver Cale Yarborough. He didn't haul moonshine like the last American hero, Junior Johnson. The guy grew up on dirt bikes in California. He's approachable. He's friendly. He's savvy. He does not wear black. He types racing reports into his computer. He cuts business deals. He has a charitable foundation. He flies in a Gulfstream jet, he's married to a New York model, he plays himself on TV shows, he does commercials, and he never seems to have a bad week. And he's the Tiger Woods of his sport.

And that would make him the biggest thing going in just about any other sport. He should be Derek Jeter or Tom Brady. Only racin' is different. The fans, many of them, want something else, something risky. Jimmie Johnson isn't a dangerous man. At least that's what they see.

And so, they boo.

* * *

Junior Johnson hails from Wilkes County, N.C., and he learned to drive a car fast by delivering moonshine to customers on time. He would outrun federal agents, or outsmart them. Sometimes he sounded off a police siren as he closed in on roadblocks, and the Rosco P. Coltranes would open up the lane and then kick the dirt as Junior roared by.

"You used to keep us up nights, Junior," those agents would say years later after they had all retired from the madness.

"Why was you losing sleep?" Junior would tell them. "There wasn't no way you was going to catch me."

Jimmie Johnson grew up in El Cajon, Calif., out near San Diego. His father was a heavy equipment manager. His mother drove a school bus. Jimmie Johnson is so polished and well-spoken, he cannot help but give off this impression that he grew up rich, that he was the kid in the neighborhood with the tricked-out Soap Box Derby car.

Only that wasn't it at all. Jimmie Johnson invented this persona he has now, the way that Jimmy Gatz created the Great Gatsby. He was just a daredevil kid who wanted to go fast. Dirt bikes. Motorcycles. Jet Skis. In his school photos, Jimmie's the one off to the side wearing a cast, propped up by crutches, sitting in a wheelchair. He broke both of his feet in a motorcycle accident when he was 14. That's when his father, Gary, said, "Son, we need to get you in something with four wheels."

* * *

Cale Yarborough grew up on a tobacco farm in Timmonsville, S.C. He tried to sneak into the driver's seat of his first NASCAR race when he was 15 years old, only they caught him and sent him home. He drove in his first race at Darlington (next town over from Timmonsville) just after he turned 18. He finished 42nd out of 44 drivers.

Two years later he got into his second NASCAR race, Darlington again. Finished 27th. Next year, third NASCAR race, he finished 14th at Darlington. Year after that he finished 30th at Darlington. He didn't seem to be making much progress.

Only Cale Yarborough didn't need good finishes to know that he could drive a car fast as any son of a gun out there. He knew that in his gut -- it's something the great ones are born with -- knew that he'd win every race if they'd just give him a car that could hold up. He kept trying to find a good car, and in the meantime he filled his time boxing Golden Gloves, jumping out of planes, wrestling alligators and, once, landing a plane though he'd never actually flown one before. Well, Cale just needed some kind of thrill. He finally got a decent car in '68, when he was 29 years old, and he won six races. He figured that it was about damned time.

Six years after that Yarborough teamed up with car owner Junior Johnson, and they were a lot alike. They both needed to win. They won three straight championships together. "Cale," Junior says, "is one helluva man."

Jimmie Johnson got into big-time racing by working for ESPN. He, like Cale, felt like he was the fastest son of a gun out there, but there wasn't any point in the 1990s to wrestling alligators. That wasn't going to get you any closer to the track.

No, Jimmie figured if he was going to make a living at this racin' thing, he would need to impress the right people. He practiced his speech patterns, firmed up his handshake, and got a job as an ESPN pit-crew announcer for the SODA series -- Short-course Off-road Drivers Association. He was on TV at 2 a.m., when nobody was watching, but TV wasn't the point. He wanted to meet the racing people who could help him. He met the Herzogs, a racing family from Missouri, impressed the heck out of them, worked out a few business deals. Together, they moved up to the Busch Series, sort of the Triple A of stock car racing.

Then, it looked like it might fall apart -- a big sponsor abandoned Jimmie -- and so Jimmie did what he does best. He worked out a meeting with NASCAR star Jeff Gordon. Jimmie impressed the heck out of him, of course, and not long after that Jimmie was driving in the big time for Gordon and NASCAR's glamour owner, Rick Hendrick.

"I know people were saying, 'Who in the heck is this kid racing for Hendrick?'" Jimmie says. And it's true, he had not been all that special in the various stock car minor leagues. But once he had the muscle of Hendrick and Gordon behind him, Jimmie Johnson became an instant star. He won the pole position the first time he ever raced at Daytona. He finished fifth in the point standings his first year, and he has never finished lower than that ever since.

Now he's simply the most dominant race car driver in America. Jimmie Johnson has won 40 races since 2002, which is more than Dale Earnhardt Jr. and Jeff Gordon have won combined. He basically needs to stay on the track on Sunday in Homestead to win the championship for the third straight time.

"Lots of people can drive a car fast," Jimmie Johnson says. "You need something else these days. It has changed. NASCAR is big business now. You need something that sets you apart."

He shrugs: "I've never been afraid to approach people. Really, that's all I had."

* * *

Junior Johnson still meets with the boys for breakfast at his garage not far from the dead racetrack at North Wilkesboro, N.C. They eat a staggering assortment of bacon and sausage, and they drink hard coffee that could corrode steel, and they talk about politics and farming and the weather and, mostly, they talk about racin'.

"These drivers have gone Hollywood," one of the boys says.

"That's all right," Junior barks back. "They make a lot of money in Hollywood."

"They make too much money," says another.

"Hell, there ain't nothin' wrong with making money," Junior says.

"They can't drive like you did Junior," says a third.

"Some of them drive real good," Junior says.

After the good old boys have gone, Junior concedes that racing has changed. It ain't all for the better, of course. There isn't as much incentive as there used to be. There's a little bit too much whining for Junior's taste. Junior never thought there was anything wrong with running a man into the wall if he needed a lesson taught. He did that to Richard Petty once. "He spun me out," Junior explains. "Either he done it deliberate or he done it because he couldn't drive. Either way, I didn't like it. We didn't need NASCAR handing out penalties or whatever it is they do now. We handed out our own penalties."

But Junior says the main thing hasn't changed -- the main thing being that you charge hard into the turns or you're gonna get passed. He says there have always been American men, and women too, who need to go fast, who need to finish first. Cale Yarborough was like that. He would get his car out front, and he would fight like a rattlesnake to keep that lead. "Cale," Junior says, "had to win."

Jimmie Johnson's like that now. He idolized Cale ("More power to him," Yarborough said). He may not want to fight the Allison Brothers like Cale did after Daytona '78. But Jimmie drives a race car like Cale. He gets his car out front, and when it's the last 50 miles of a race everybody in NASCAR knows that the toughest thing in the sport to do is pass Jimmie Johnson.

And that's what matters. See, Junior said, not all the dangerous men come from the South, and they haven't all done jail time, and they haven't all pulled water moccasins out of swamps with their bare hands.

"If a guy can drive, a guy can drive," Junior Johnson says.

Tale of the tape: Jimmie Johnson and Cale Yarborough.