The NFL and others need to stop coddling professional athletes

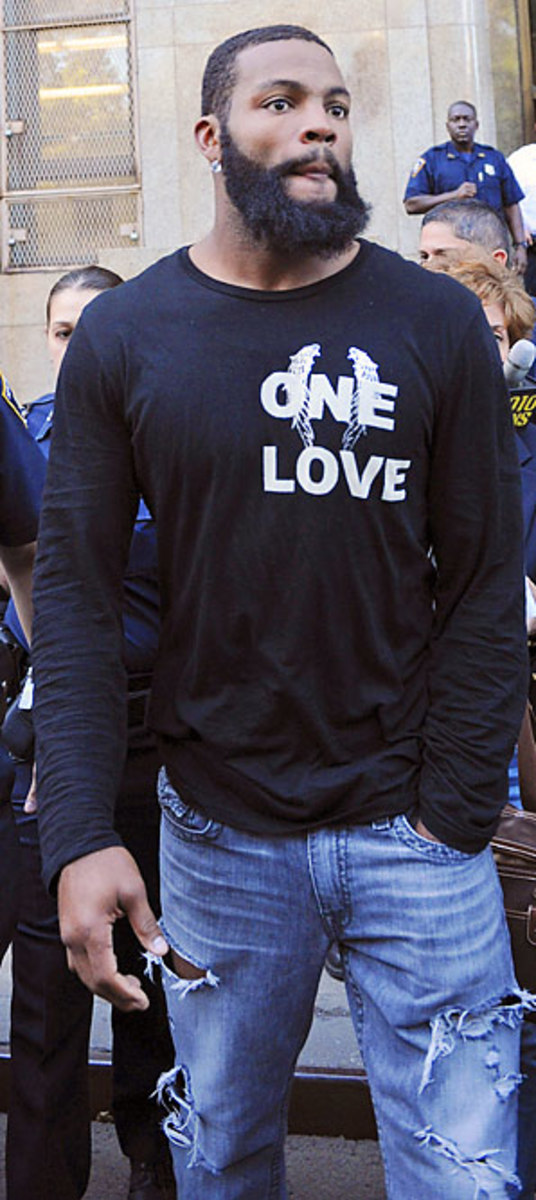

Here in New York, the big news this week has been Braylon Edwards, the thinks-he's-Wesley Walker-but-plays-like-Lam Jones Jets receiver who was arrested early Tuesday on drunken driving charges. The Big Apple's dueling talk radio stations are especially abuzz, with cries of Edwards' need to be suspended, to be released, to be traded, to be fined, to be signed by ABC's reality TV division and forced to Jell-O wrestle the guy who played Horshack on Welcome Back, Kotter.

Lost amid all the yelling and screaming and shouting, however, is a vital nugget of information that, quite frankly, blows my mind: The Jets, as well as the entire NFL, provide their players with free taxis.

Really -- free taxis! For everyone! Well, not for you or me. But for everyone who receives a (astonishingly bountiful) paycheck with the NFL insignia on it. The Jets call their system the Player Protect Program, which allows members of the team no-questions-asked rides at any time, day or night. The league, meanwhile has its own Safe Ride operation that extends Jet-like benefits to everyone on a roster.

High on crack? Taxi!

Busted with two transvestite hookers and Lyndon LaRouche? Taxi!

Wearing one of those ties designed by Kwame from The Apprentice? Taxi!

Thanks to the NFL, taxi drivers reign and taxis rain. Two blocks, three blocks, a trip to Waldbaums, a cross-country journey from the New Meadowlands Stadium (gaudy) to the old Oakland Coliseum (gross). Wherever a professional football player wants to go, the trip is taken care of. Literally.

But while I personally would love to wiggle my nose and have a free ride appear ("Take me to Cheryl Cole's house! Snap, snap!"), one must wonder how little the Jets and the NFL think of their players to have such a perk in place. Braylon Edwards, for example, is a 27-year-old adult who attended the University of Michigan. He runs his own charitable foundation. He makes $6.05 million this season. If he needs a free taxi to avoid driving drunk, well, what does that say about Braylon Edwards?

More to the point, what does it say about Edwards' irrefutable history as a coddled athlete? The commissioners of America's major professional leagues talk a good game about helping their players adjust to life after sport. They mention excellent health coverage and myriad career counseling opportunities and offseason internships galore. Yet if these operations truly want to do athletes right, they'll start with one easy step: Stop coddling.

Seriously, stop it. As of today, every active member of the four major professional sports leagues is at least 18. That means every active member of the four major professional sports leagues is an adult. That means you, Mr. Team Owner, no longer need to have a person who will book your players' offseason vacations, cook their meals, clean their laundry, provide investment advice, suggest spots to eat. You no longer have to give free shoes, gloves, T-shirts, pants, golf clubs, drinks or dinners.

Of the thousands of since-retired athletes I've covered through the years, only a handful have left their sports without encountering trouble. The rest walk into the bank without grasping how to write checks; enter a supermarket not knowing frozen waffles and frozen pancakes are usually side by side; enter marriage not realizing that maybe, just maybe, getting a lap dance at a strip club might no longer be kosher.

A couple of years ago I met Clayton Holmes, a former defensive back with the Dallas Cowboys who earned two Super Bowl rings in the 1990s. Like Edwards, Holmes had once signed a million-dollar contract. Like Edwards, Holmes liked to imbibe recklessly. Like Edwards, Holmes was treated as a 6-year old. Just as the Jets do for Edwards, the Cowboys took care of all of Holmes' needs. He was a king. An emperor. A God.

When we met in his hometown of Florence, S.C., Holmes was living in the front yard of his mother's house, beneath a rickety shed lacking running water or a single light bulb.

Without a car or bike, he had no means of transportation. Holmes was depressed, broke, isolated and alone.

He could have used that taxi.