Hot Stove Roundup: Trades reveal talent drought at shortstop

Stop and think about this question for a moment: How many really good shortstops are there in baseball right now? Troy Tulowitzki is pretty great. So is Hanley Ramirez. Who is the best in the game after those two? Derek Jeter and Marco Scutaro are good, and also old. Yunel Escobar has nice numbers, but was traded for a 33-year-old Alex Gonzalez who struggled to slug .330 in the middle of a pennant race last year. Stephen Drew and Alexei Ramirez are nice players, and not quite stars. Elvis Andrus and Starlin Castro are years from their primes; Jose Reyes has been injured during his.

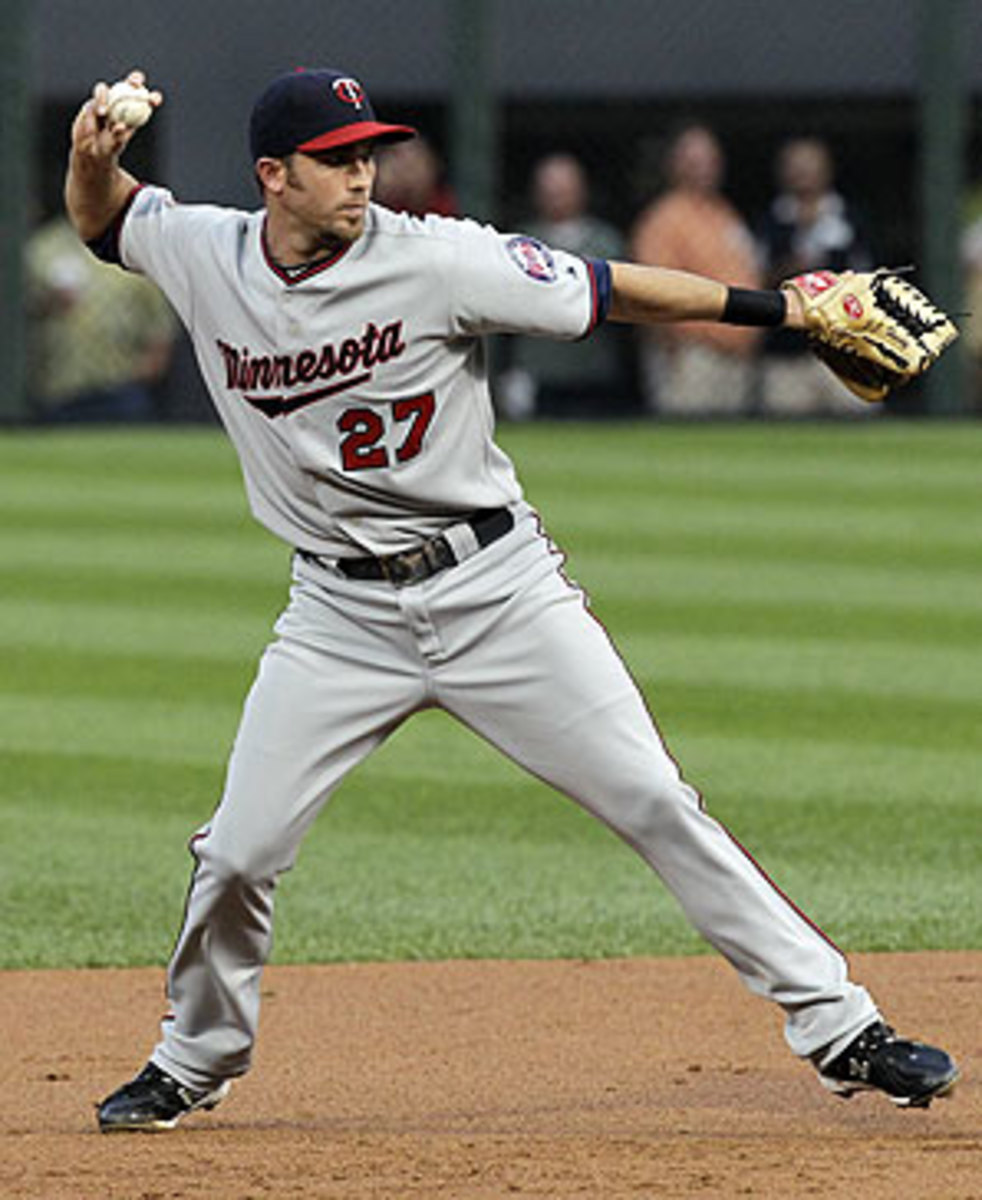

The point here is just that while good, sound, solid, harmless shortstops would seem to have some value these days, they apparently don't. The Minnesota Twins, by anyone's reckoning a strong contender, rid themselves of J.J. Hardy in exchange for the oft-traded "live arms," the same types that are also involved in a deal (which may or may not ever happen) that would move Jason Bartlett from the Tampa Bay Rays to the San Diego Padres. From this one can infer that we're just in a bit of a positional drought right now. Everyone other than the greats is part of a drab gray mass.

Here lies opportunity! You'll often hear it said of this or that infielder --Washington's Ryan Zimmerman, say, or free agent Adrian Beltre -- that he could handle shortstop. Someone should put the theory into practice. There just aren't a lot of top shortstops around right now. Make one of your own and you'll have one.

The Boston Red Sox have won a lot of games and made a lot of money during general manager Theo Epstein's tenure not just because they've had good players and high payrolls, but because, say what you like about it, they've had an ethos.

One tenet of it was not signing players to deals longer than five years. Another was not spending a lot of money on the wrong end of the defensive spectrum. After a week in which they signed left fielder Carl Crawford to one of the 10 largest contracts in history and traded several of their top prospects for first baseman Adrian Gonzalez, these are, in Boston at least, dead ideas.

If you were Epstein, you might do the same. Over the past several years, he's made his largest and chanciest investments in pitching, spending over $200 million on Josh Beckett, John Lackey and Daisuke Matsuzaka. Anyone who's done that will develop a fond regard for position players, who age more gently and reliably than pitchers.

Moreover, Epstein faces a new world. Baseball, as part of its ongoing quest to become more like the much-loved sport of hockey, is going to introduce a fourth round of playoffs. This affects the Red Sox more than any other team. For years they've been built not to be the best team in their division, but to be a playoff qualifier. Faced with the idea that a mere 95 wins might not be worth anything past the chance to get knocked out by a weak team in a three-game playoff, though, they're going to have to improve, and go head up with the New York Yankees. That means spending, even if it means you spend $142 million on the poor man's Tim Raines.

It makes a good testament to how well the Red Sox have been run that they can bring on two players like this without destroying their farm system or even really raising their payroll, and that there is more coming -- they have nearly $60 million in basically dead money coming free next year, and will surely spend it. Whether they'll look so smart years from now when they have several decrepit designated hitters on their roster earning tens upon tens of millions of dollars is a different question. I think they'll wish they had kept to their ethos.

This was a good week for Jayson Werth and his family and anyone who might be looking to sell them stakes in Arctic oil exploration outfits, personal missile silos and such, as the man signed a seven-year, $126 million contract with the Washington Nationals. It was an equally rotten one for the city of St. Louis and its many stout, cheerful citizens. Albert Pujols, the man with talent on loan from Xenu, is in the last year of his contract. If you can figure how the Cardinals will be able to pay out on a new one you ought to call them.

The problem is not the total value of Werth's risible contract, but its annual average value of $18 million per year, which is... clearly fair. It might be more than that. Had some team like the Red Sox been able to sign him to a three-year deal at $21 million per year, the baseball commentariat would have blown plastic horns in praise.

Sadly for St. Louis, Pujols is twice the player Werth is, which I don't mean in a figurative sense. By Baseball-Reference.com's math, Pujols has accounted for an average of 8.7 wins above replacement over the past three years, against Werth's 4.2. He is also younger than Werth by a year. If Washington's new outfielder is worth $18 million a year, Pujols is worth $36 million a year. Probably more.

A number like that doesn't work for anyone, and it certainly doesn't work with the Cardinals' payroll. In 2012, for example, they have $37 million already committed to Matt Holliday, Kyle Lohse and Jake Westbrook, as well as a $9 million option on ace Adam Wainwright, which they'll presumably use. Running a $110 million payroll -- that would be $11 million higher than any they've ever had, and $16 million higher than last year's -- they would still have just $28 million to fill out the rest of the roster if Pujols' salary came in at $36 million. That sounds like a lot, but in a market where Carlos Peña, a 32-year-old first baseman with a .196 batting average, costs $10 million, it's not.

Unhand the blowgun. The point isn't that St. Louis can't, shouldn't or won't retain their man; they can, should and probably will. Rather it means that his talent isn't on the same scale as baseball's economy. Former commissioner Fay Vincent recently wrote an article arguing that more clubs should offer top players equity stakes in lieu of salary. It seems silly until you consider this: Pujols' agent Dan Lozano can, right now, with a completely straight face, argue that his client is worth a 10-year, $400 million contract. According to Forbes magazine, the value of the St. Louis Cardinals franchise is $488 million.

While the Cardinals mull the fate of an inexpressibly great player, poor Arizona Diamondbacks GM Kevin Towers is stuck dealing with inexpressibly bad ones. Last year's Diamondbacks had a hilariously wretched bullpen, one of the worst anyone has ever seen. The top six offenders were Chad Qualls, Bob Howry (who knew he was still pitching?), Sam Demel, Leo Rosales, Esmerling Vasquez and Juan Gutierrez. They combined for a 6.31 ERA in 214 innings.

This makes Towers' late flurry of activity comprehensible. He traded third baseman Mark Reynolds to the Baltimore Orioles for pitchers David Hernandez, who has a 49/13 K/BB rate in 39 2/3 career relief innings and seems very much like the type who might thrive in one-inning stints, and Kam Mickolio, who throws hard. He signed Melvin Mora to replace Reynolds. (This is inoffensive; Mora is old and terrible but cheap, while Reynolds is young and okay but expensive.) He signed J.J. Putz, who was superb with the Chicago White Sox last year, to a one-year deal with a club option.

Because last year's relievers were so bad -- and this is the significant point -- all of this was the rough equivalent of adding Pujols while saving millions of dollars. While not as extreme, most rosters, including those of contenders, have a similar type of slack in them. Watching Towers at work should give the clue to would-be contenders with bum-riddled rosters.

The Diamondbacks, who lost 97 games last year, are still going to be flat bad. Add the real Pujols and they probably still wouldn't be a .500 team. Still, they should be a lot nearer to watchable. Next, Towers should get a real leftfielder. Nominal incumbent Gerardo Parra has slugged .389 in 253 career games. That doesn't make him the equivalent of a Snakes reliever, but he's close.

My favorite deal of the week, for reasons wonderfully described by my colleague Joe Posnanski, was Kansas City Royals GM Dayton Moore's signing of Jeff Francoeur. It was inevitable, like Teddy Wilson and Billie Holliday, except nothing at all like that. The eschaton is more near being immanentized now that this has happened.

My second-favorite deal of the week brought Miguel Cairo back to Dusty Baker's Cincinnati Reds. A man who has been 37 for dozens of years now, a man who can play everywhere nearly ably, a man who has inexplicably found sinecures on Joe Torre's Yankees, Tony La Russa's Cardinals and Charlie Manuel's Phillies while failing to get on base three times in 10, a man who when given the at-bats will surely rate among the league leaders in sacrifices, a man of no demonstrable value on a field, he is the perfect Baker player.

In 2003, when Baker was managing the Chicago Cubs, he made Lenny Harris, a 38-year-old career pinch hitter who hadn't had a starting job in more than a decade, his third baseman for a time. It was epic. At the end of May the man was hitting .209, and fielding like his hands were stuffed in small mouth jars. That got him out of the lineup, but not out of the game. Over the next two months he played in 34 more games, hitting .143 with a .159 slugging average and was eventually released. It was the most putrid stretch of hitting you'll ever see. Baker refused to stop using him. He believed in him.

Last year, a half-decade past the one decent year he had, when he bafflingly hit .292 with power for the Yankees, Cairo was again moderately useful. Under Baker's benevolent hand he hit .290, got into games at first base and rightfield and even designated hitter, and clouted more home runs (four) than he had from 2005 to 2009. I suspect that he will never lose Baker's loyalty, even if he hits .143.

As SI.com has reported, multiple teams, including the Yankees, are now offering Cliff Lee seven-year contracts, making happy days for all free agent aces who look like Walker Evans photographs of Depression-era migrant farmers. Whereas the Werths will be limited to only so many private spaceship rides, the Lee clan will doubtless be able to buy tickets in bulk and pass them out to Salvation Army bell ringers. Sad days are likely on the way, though, for whoever actually lands him. They will understand why snooty economists call it the winner's curse.

Take this as illustrative. From ages 29 to 31, Lee went 48-25 with a 2.98 ERA in 667 1/3 innings. At the same ages, Tom Glavine went 45-25 with a 3.00 ERA in 674 innings.

This isn't a perfect comparison; Lee has better stuff and truly freakish control, is not reliant on a personal strike zone, and has proven that he can pitch at his best in October. Still, from ages 32 to 38, Glavine went 109-72 with a 3.49 ERA, averaged 221 innings per year, won a Cy Young award and finished first runner-up another time. That is a pitcher who aged exceptionally well, and yet while Lee would be lucky to match his performance, if he did he would probably be a bit of a disappointment. Glavine, forever heaving balls in hopes they would be called strikes, is not quite the pitcher who comes to mind when one hears phrases like "$175 million" and "best-paid pitcher of all time."