Gibson among new managers changing culture of their clubs

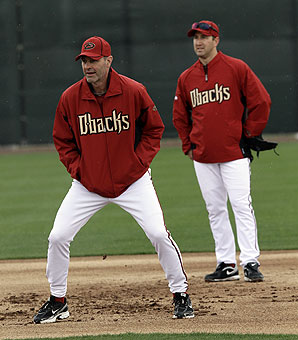

The cultural change is tangible. Gibson is pushing his players to hit the weight room more. He has instructed his pitchers to work more on their hitting and bunting. He has brought in Navy SEALS to talk about commitment and teamwork.

He has banned all cell phone conversations from the clubhouse -- and no texting, iPads and computer usage 30 minutes before the first pitch of games. That's a radical departure for a clubhouse that had been chock full of remote control vehicles, air soft guns and assorted other toys -- all gone now.

The Diamondbacks, a team that lost 97 games last year, could have known spring would be different by doing a little homework. The Dodgers signed Gibson as a free agent after they lost 89 games in 1987. Before the team's first spring training game, pitcher Jesse Orosco pulled a prank on Gibson by lining his cap with eyeblack. As Gibson began to sweat, the eyeblack dripped down his head and Gibson wiped it all over himself. Gibson did not laugh. He stormed off to the clubhouse, telling manager Tommy Lasorda, "You find out who did this, because I'll tear his head off."

Nonsense like that, Gibson figured, was why the Dodgers were losers. That year, with Gibson "changing the culture," they won 94 games and the world championship.

The Diamondbacks are unlikely to win the NL West, nevermind the World Series. Only the Pirates allowed more runs last year. But Arizona will be better, and Gibson and his coaching staff full of accomplished former big leaguers (Don Baylor, Alan Trammell, Charles Nagy, Eric Young) are just a start to the improvement. The bullpen (5.74 ERA, 62 homers) has to be better and Justin Upton, who turns 24 and has yet to play 140 games in a season, is a breakout year waiting to happen if he learns how to handle the mental and physical grind of a season.

"If we can take that into the 150s," Gibson said of Upton's games total, "the numbers will be there."

Gibson has no set lineup yet and plenty of jobs open, which suits his message about competing just fine. Last week the Diamondbacks worked out twice through rain, wind and chill. Said GM Kevin Towers while getting soaked himself, "The players know better by now not to expect an air horn to go off, sending everybody inside. Gibby said, 'We'll be playing in weather like this Opening Day in Denver. The only way we're coming off the field is if it snows -- maybe if it snows."'

Gibson isn't the only cultural change for the Diamondbacks. Their Scottsdale training complex, Salt River Fields, which they share with the Colorado Rockies, redefines state of the art by leaps and bounds. Nothing else comes close to Salt River Fields when it comes to design, functionality, resources, luxuries and sheer size.

The fascinating part is how Arizona and Colorado have put their own organizational personalities onto their halves of the complex. Arizona made its practice fields more fan-friendly in terms of access, installed a media workroom and separated its major and minor league workout and lunch rooms. Colorado chose not to include a media workroom in its massive four-story main building, opted for huge workout and lunch rooms so that minor and major leaguers could mingle and hung murals with inspirational words throughout the expansive corridors.

The Rockies' side has much more of a football flavor, a reflection of late Rockies president Keli McGregor, a former NFL player. The gigantic, stunning workout room -- think of it as the best health club in the Phoenix area -- is named for McGregor, who was instrumental in the design of the complex.

The Rockies also have a 200-seat theatre with a big screen for team meetings, just as you might find in a state of the art NFL facility. (The Diamondbacks don't have one.)

Why does a baseball team need an NFL-style theatre? Recently, manager Jim Tracy wanted to impress upon his players the importance of the kind of spring training drills that can seem tedious, such as pitchers' fielding practice, or PFP. He assembled his players in the theatre and rolled a video clip from a game last year in Atlanta on April 18.

The Rockies led the Braves, 3-2, when pitcher Franklin Morales obtained a grounder to first base that should have been a game-ending double play. But Morales was slow getting off the mound to cover first base, costing Colorado the last out that should have won the game. Two batters later, Jason Heyward hit a two-run single off Morales to give Atlanta the win, 4-3.

It was only one missed play in only the 12th game of the season. But then Tracy pointed out its importance: if the Rockies cover first properly, they win the game, and if they win the game, on the morning of Sept. 19 they are tied in the loss column with the Braves for the wild card lead -- instead of being 2 ½ games behind Atlanta. And there, for all to see on the big screen, is why the details are important.

Chalk up the Brewers as another team that is "changing the culture" and liking it. Manager Ron Roenicke, who replaced Ken Macha, is running a detail-oriented camp that, according to leftfielder Ryan Braun, "is just tremendous. Everything is positive. The outlook is just extremely positive every day. It's exciting."

Said another Brewer, "Ken is a great baseball man, but sometimes he just left the players on their own."

One area Roenicke and pitching coach Rick Kranitz are emphasizing is the pitchers' responsibility in defending the running game. Last year only the Cubs, Pirates and Diamondbacks threw out a lower percentage of basestealers in the NL than did Milwaukee (24 percent). Just behind the catchers where the Milwaukee pitchers throw their bullpens are two signs that read, "Milwaukee Brewers Pitching. Hold the ball. Hide the ball. Quick to the plate. See the runner. Vary your looks."