MJ's record day in 1986: 63 points, a loss and a learning experience

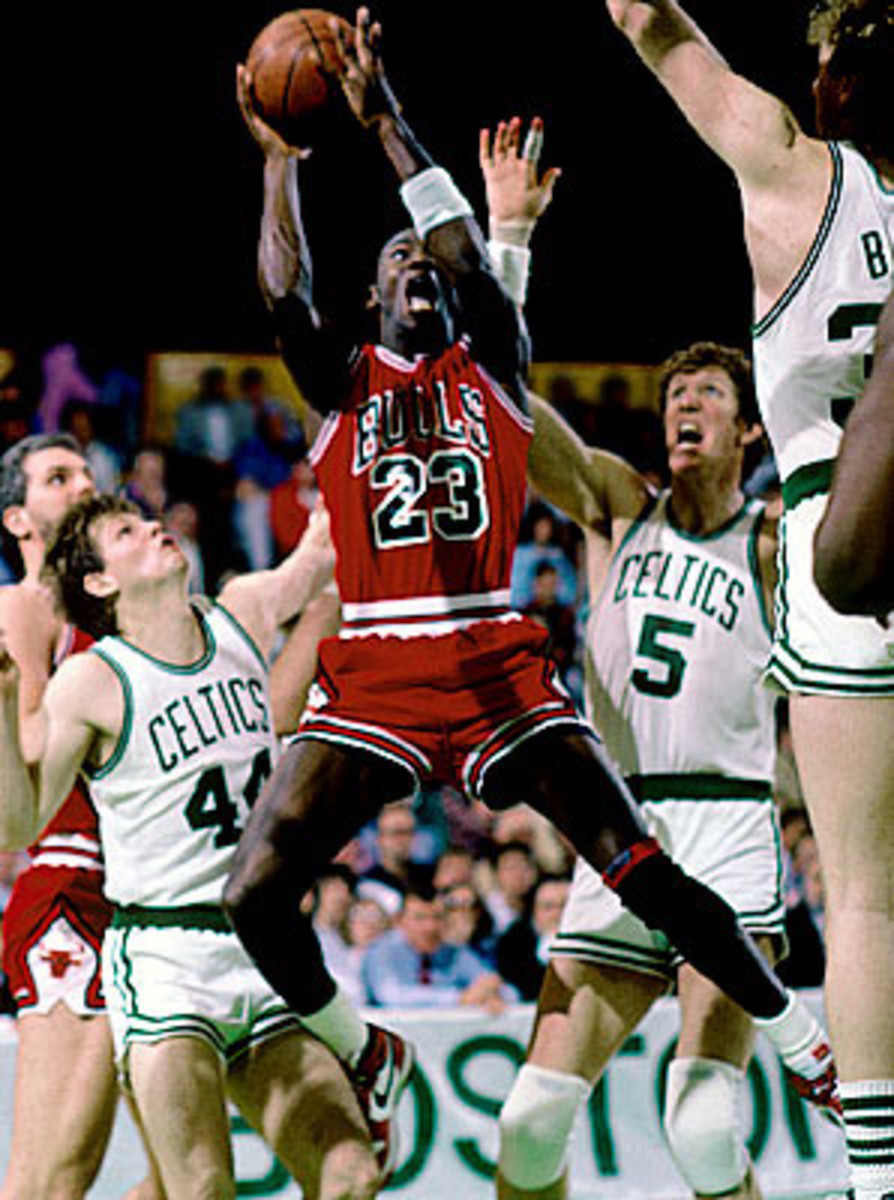

Exactly 25 years ago today I watched from behind the east baseline of Boston Garden, the parquet laid out before me, as Michael Jordan went for 63 points in a playoff game.

No player before him had scored as many on a postseason stage, not even Elgin Baylor, who once sprang for 61 in the same building. No one has scored as many since.

I should confess: I wasn't there to bear witness to His Airness. I was there to document the march to a title of the 1986 Boston Celtics, for which a sturdy case can be made as the greatest team of all time. Indeed, the Celtics beat the Bulls that day, even if only by 135-131 and the grace of double overtime.

But I knew enough not to let my eye stray from No. 23. To me, Jordan had already cemented a reputation as The Great Portender. I'd broken in at Sports Illustrated as a college basketball grunt, fact-checking Curry Kirkpatrick's 1982 Final Four story, which described how a gangly North Carolina freshman knocked down a mid-range jumper to deliver Dean Smith's first NCAA title.

A year later, because he was now a sophomore, Jordan had Smith's permission to engage in preseason conversation with the media, which included me. As we sat in the chairbacks of Carolina's old Carmichael Auditorium, he recounted how he picked up the habit of sticking his tongue out from watching his dad do the same whenever James Jordan concentrated on some task in the backyard of their home in Wilmington, N.C.

As a North Carolina junior, late in what would be his final season as a Tar Heel, Jordan visited Cole Field House to take on Len Bias' Maryland Terrapins, and everything I saw that day foreshadowed the success he would enjoy at the next level. Late in the game Jordan pounced on a lazy Maryland pass to the wing, and years later I wrote about what happened next: "He bounded down the floor and, wedging the ball in the crook of his wrist, described a pendulous arc with his arm before flushing the kind of dunk that, over his NBA career, would become a film-at-11 commonplace. It was a coda to what had already been a valedictory performance in Jordan's final visit to Cole. Afterward someone asked him if he intended to send some sort of message with that last one. Jordan replied like an efficient secretary: 'No messages.' "

For the 1984-85 season, like Mike I moved to the NBA, writing our first cover story on the new Bull, prosaically billed A STAR IS BORN. "I hope," he told me, as I followed the Chicago rookie during an early-season swing out West, "to play in at least one All-Star Game."

Gallery: Jordan's top 23 SI covers

Which brought us, in Year Five of our relationship, to North Station.

First, a little back story: Jordan had broken his left foot early in the 1985-86 season, and Bulls management -- to say nothing of the team's orthopedist and the various Mr. Ten Percenters who figured to cash in handsomely on MJ over the long haul -- all wanted to cut their losses, permit that be-swooshed foot to thoroughly heal, and start afresh in the fall.

All this had left Jordan appalled. He all but accused the Bulls of sandbagging, and vowed to spend the spring playing pick-up ball in Chapel Hill if they wouldn't let him come back for the season's final weeks. Rather than risk a prolonged rift with their young star, the Bulls took him back in mid-March, and he willed Chicago into the East's final playoff spot.

Jordan had scored 49 in the first game of the series against Boston, cycling through a mix of floaters, dunks and long jump shots, like a pitcher mixing sliders, changeups and curves. And now, having already laid waste to the best defensive guard in league, Dennis Johnson, he toyed with whichever Celtics big man -- Robert Parish, Kevin McHale, Bill Walton -- switched over to help. "I don't have a word for today," Boston coach K.C. Jones said after watching Jordan's performance in Game 2, and that pretty much gets my own thoughts on the afternoon.

Covering the early Jordan was like that. He would tax the sportswriter's powers of articulation. Jordan would lay down these markers, and as he did so you couldn't help but recognize them as such, in real time, as if you could see posterity seep into the cracks of the ground around them. That's how starkly they popped from their context, and how thoroughly you sensed that he was in the early stages of remaking the pro game. This was more than a matter of regarding the Portland Trail Blazers as witless for choosing Sam Bowie over MJ in the 1984 draft; any caller to sports-talk radio could do that. It was, rather, to behold that he could dominate a game from the wing, with a sally to the basket or an incursion into the passing lane, as much as anyone ever had from the post with a skyhook or a blocked shot. And it would all be much more sudden and electric and irresistible.

The markers he laid down later were substantial too, of course -- the first title and the sixth; the capstone of his post-baseball comeback, when he dropped what Spike Lee would call a "double nickel," 55 points, on the Knicks in a regular-season game at Madison Square Garden; the succession of foils (Craig Ehlo, John Starks, Bryon Russell) who help us remember his greatest moments by.

But here's the difference: Jordan walked away from all of those engagements a victor. There was something so much more human about Jordan's performance on April 20, 1986, because he lost. He and the Bulls were still in development. He would endure another four seasons of playoff disappointment under two more coaches, Doug Collins and Phil Jackson, before fully absorbing the Tao of Titledom that Jackson came to Chicago to peddle. Only in 1991 did Jordan finally learn to subordinate himself enough for the Bulls to win a championship.

Looking back, Jordan had to be a loser that day in Boston a quarter-century ago. Indeed, as the best team of all time, those Celtics had to be the winners, in the face of the greatest individual playoff performance of all time, to further the young Michael's education in that most essential of hoop truths: that, in the end, a full team will beat any single player, no matter how good.