Finding meaning in cliché: What really happens at SEC Media Days

The workers are very busy, the materials very raw. No, that's the wrong word. Raw would mean fresh, even dangerous, and the materials here are nothing like that. Tired, maybe. Dry or lifeless. One coach fades into another, one phrase into the next. A machine could deliver these lines. He would never misspeak.

The first game is so critical if you want to compete, he would say, in a tone of unwavering resolution, using actual words and phrases spoken by coaches at this year's SEC Media Days. We got to go play the games. Practice hard, play hard. Play every play, every game for 60 minutes. Step up and make those game-winning plays. Impact the game in a positive way. Going to play a tough team every single week. Week in, week out, on a consistent basis. From the beginning of the game 'till the end.

It's going to be a big game, he would continue. Hopefully we can play our best game there. Utilize our personnel. You got to go out and prove yourself. At the end of the day, you have to go out and play and compete at a very high intensity level. Speed level. Comfort level. Talent level. Meet the expectation level that we expect. Depth perspective. Proximity standpoint. Structural and schematic standpoint. Continue to move forward. With dedication, with buy-in, with a proven track record of success. Grow the offense. Grow the program. Build the program. Market the program. Fundamentally and structurally. Sky's the limit, sky's the limit, sky's the limit.

Should the coach take all the blame for this colorless tide of gobbledygook? No. They would rather be anywhere else, but they stand at the elevated lectern, staring at the arsenal of MacBooks and white-hot camera lights. They would rather be almost anywhere else: on the field in the sunshine, in a boat on a lake, in the kitchen with a daughter or son. But no. They must come here, a day or two earlier every year, to feed the hungry fans.

And with what? If one really has some secret plan to make his team better, would it really be smart to tell the whole world? If there's a freshman who just might win the Heisman, would it really be wise to brag about him before the first down is played? No. But they have to say something, anything, and the writers are waiting to pounce. They are not friends. They are strangers, hundreds of strangers, unpredictable in many regards, utterly predictable in this one: If and when a coach stumbles, they will tell everyone. Immediately. Probably via Twitter. This applies whether you're a newcomer, like Gary Pinkel of Missouri, and you fail to hate Joe Paterno enough to suit today's popular sentiment; or you're an old jackal, like Steve Spurrier, and you briefly (but conveniently!) forget Cam Newton's existence.

Look around. Writers may be at the event, but most of them aren't even looking at the speaker. They are staring at their MacBooks, doing Lord knows what. Probably watching each other lampoon coaches on Twitter. In the past, they might have been taking notes, but there's no need for that anymore. A stenographer sits in a chair banging on what looks like a tiny gray piano, giving each word the permanent weight of a court proceeding. These words will be sent to everyone, almost immediately, whether they bothered to sit here or not.

So, is this the writer's fault? Of course not. He is hungry, too. Hungry to do good work, to write a good story, to keep his editor and his legion of readers mollified with some shred of actual news. And here he gets none. Oh, he's working, all right, probably twelve hours a day, sleeping in a strange bed, texting his wife and children between these mind-numbing sessions. He's building clever vehicles for the transmission of these nonstories, but what is he really getting? From a proximity standpoint? From a depth perspective? Is his talent level being properly utilized? Is he impacting the game in a positive way? Well, he does have a certain comfort level. He can commiserate with other writers at the end of the day over a Sweetwater and a filet of Cajun-grilled snapper that is probably paid for by someone else. At least they can sit around and talk about what did not happen.

This thing lasts three days. According to several veteran guests, this year's event is especially uneventful. No tempests, no teapots, no mountains, no molehills. The highlight of Tuesday takes place not in the actual ballroom but on Twitter, of course, when the popular satirist Spencer Hall draws a crude picture of Steve Spurrier floating above the grass on the wings of an angel. This is a fairly appropriate commentary on Spurrier's talk, during which it became abundantly clear that he thought the Gamecocks were nothing before he arrived to save them all. So, in Spencer Hall's Twitter drawing, Steve Spurrier floats, and lightning pours from his staff, and it touches the head of a mindless Gamecocks fan. The fan thanks him for this precious gift.

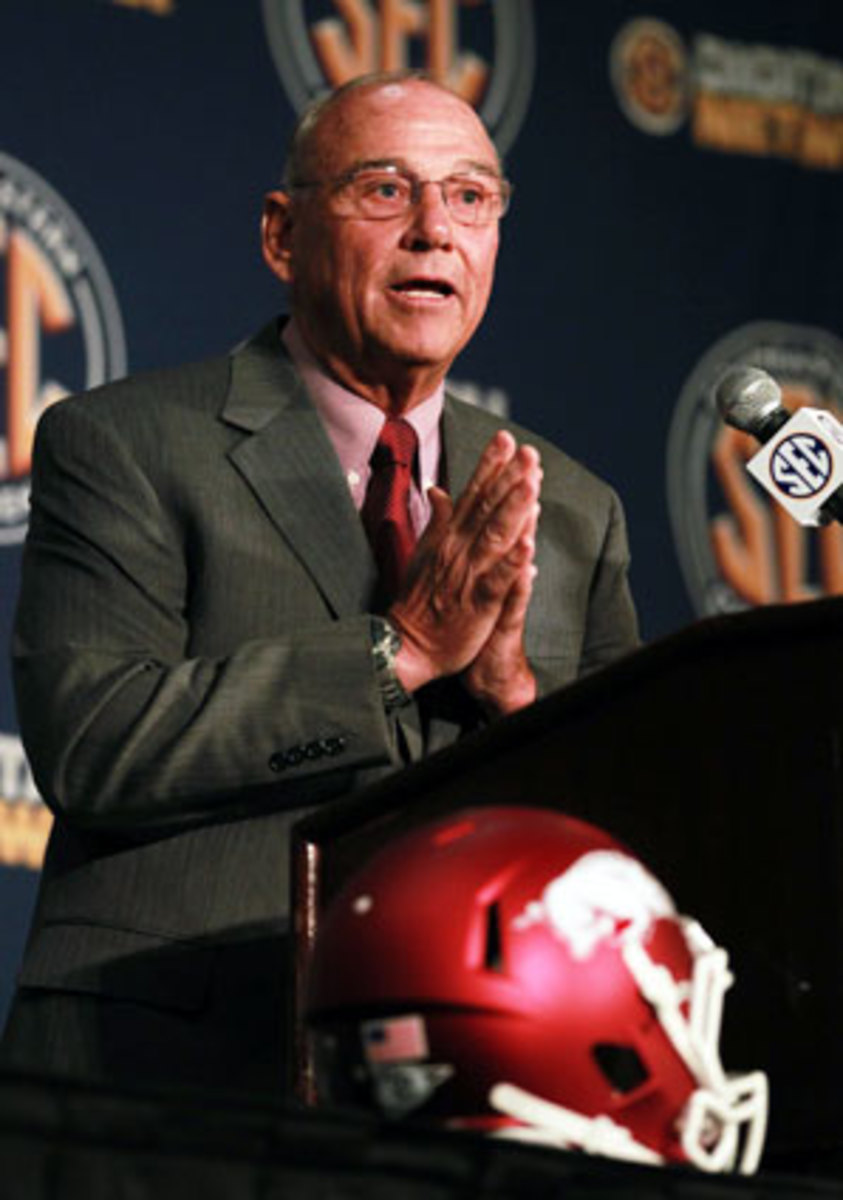

The second day is Wednesday and it shows some early promise. Everyone knows John L. Smith of Arkansas is coming, and everyone knows that he has the job because Bobby Petrino was fired in the aftermath of that thing with the blonde and the motorcycle. Everyone also knows that John L. Smith will get asked about Bobby Petrino, and that might cause some fireworks.

Now, another thing about these coaches. You'd think that a football coach in the SEC would have to be a good ol' boy, but that is no longer the case. Dan Mullen is not from Mississippi State; he's from New Hampshire. Les Miles is not from Louisiana State; he's from Ohio. John L. Smith of Arkansas could pass for a retired insurance adjuster from rural Pennsylvania and is, in fact, from Idaho. When he speaks the phrase Hog Nation, it sounds foreign on his lips.

The second question posed to Smith mentions "the Bobby Petrino stuff," but Smith gives a convincing non-answer that leaves him in the clear. Then, a few minutes later, it gets interesting. Someone asks, "Would you like to be the Arkansas coach for more than one season?"

"Well, certainly," Smith said. "Do I look stupid? Don't answer that." And he smiles, and the room fills with hearty laughter.

Then it gets more exciting. Some guy near the front starts to ask a question, and Smith promptly cuts him off.

"They still put up with you in Memphis?" he said.

This is highly unusual. So far most of the talk has been crushingly impersonal, like a Turing test in which both sides fail. Eye contact is rare; actual dialogue almost nonexistent. And now John L. Smith is acknowledging a writer's presence!

The man continues with his question. And it's a bold one.

"Was contact between you and Arkansas initiated before Petrino was officially dismissed or after? How was it initiated? Also, had you have any conversation or conversations with him about the football team?"

An open trap.

"Could we move on to the next question?" Smith said. "At least one with intelligence?"

Tension in the ballroom. Then Smith seems to soften, and he actually gives a firm answer. "No, to my knowledge, we did not have any interaction 'till after Bobby was gone."

Case closed. Still, a nonstory is better than nothing at all. Spencer Hall has something to Tweet about.

I wish I had a bear on a leash under this table because I would ask John L. to fight it and he would.

John L. is barking at an Arkansas conspiracy theorist right now. Like, literally barking.

And then the moment is gone, the session over. People begin to forget about the unknown "Arkansas conspiracy theorist" who dared to challenge John L. Smith. Who was this man? Where did he go? Do you know? Do you know? Zack Higbee, the director of football media relations for Arkansas, seems like a good person to ask. But he has no idea.

Doug Segrest, a veteran reporter for the Birmingham News, is standing by the escalator. He knows the guy. Sure, he says. That was George Lapides. He's right over there.

George Lapides (pronounced LA-PITAS) is a sprightly old man with close-cropped white hair, bifocals and a genuine old-time Southern accent. He is very friendly. As it turns out, he is also the single best person to ask about the history of this event. He's been covering it for nearly 50 years.

"I've been to every one," Lapides said. "I think there are only two of us still alive. And I'm the only one still working."

It was different back in the '60s. There were fewer than 40 people covering the SEC, as opposed to 800, and they could all fit in a Martin 4-0-4 airplane. Which they did. Instead of sitting around a hotel they flew together from one SEC school to the next, talking with coaches and players and getting to know the football landscape. In Gainesville, coach Ray Graves hosted them for dinner at his own home. Back then the coaches actually talked to you.

One day Lapides watched a scrimmage from the sideline with Georgia coach Vince Dooley, who was talking about a freshman running back. Dooley said the kid wouldn't be ready for another year. They stood together as the defensive lineman Eddie (Meat Cleaver) Weaver smashed the kid and forced a fumble.

I told you he's not ready, Dooley told Lapides.

The kid got the ball again, and got hit again, and fumbled again. Not ready? Well, maybe he was. On September 6, 1980, Georgia played Tennessee, and Dooley gave the kid another chance. That led to this immortal play-by-play call from Larry Munson, the voice of the Bulldogs:

Herschel Walker went 16 yards! He bowled right over orange shirts, just driving and running with those big thighs. My God, a freshman.

Another time, George Lapides was sitting in the school cafeteria with Auburn coach Pat Dye. And Dye said, I got me a running back right now who could start for the 49ers, Rams and Falcons.

Who's that? Lapides asked.

Vincent Jackson, Dye said.

Lapides asked if he could talk with Jackson. Dye said he didn't usually allow freshmen to talk to reporters. Lapides pushed a little, and Dye relented. Lapides got an interview with young Vincent. He wrote a column for the old Memphis Press-Scimitar proclaiming that he'd found the next Herschel Walker.

Well, not exactly. He had actually found Bo Jackson.

But Lapides may have been closest with Bear Bryant, the king of the Crimson Tide. Bryant used to call his house at night, and if his 10-year-old son, Michael, answered, then Michael and the Bear would chat like old friends for 20 or 30 minutes. When George Lapides was hospitalized for back surgery, Bryant sent him a framed picture with a note that said get well soon.

Those were the days.

Oh, by the way: that little conversation in the ballroom with John L. Smith? Not actually a confrontation. Lapides covered Smith when Smith was still at Louisville. They used to play in golf tournaments together. Smith called Lapides "Gorgeous George." They could go back and forth that way in the ballroom because they are something like old friends.

Smith confirmed all of this in a brief interview between visits with Fox Sports and ESPN.com. "You called each other by name," he said of the old days. "There were times when you could say, 'Don't print this,' and then say a few things, and they wouldn't print it."

Imagine saying that to several hundred news-starved reporters with their fingers hovering over the Tweet button.

The next morning, Alabama fans press seven and eight deep against the crowd-control barriers in the lobby. They want to see Nick Saban, the coach who has brought them two national titles in the last three years. Many people say Saban's arrival will be the highlight of the event, but George Lapides is not holding his breath. He does not know Saban. Nor does he really know Derek Dooley, the Tennessee coach, even though they live in the same state and Lapides was once close friends with Dooley's mother and father. "I don't even know 90 percent of these people," Lapides said the day before, "and I'll tell you 99 percent of them don't know me."

Now he's doing his radio program, live on Radio Row near the entrance to the Riverchase Galleria mall, for Sports 56 WHBQ in Memphis. He says it's the longest-running sports talk radio show in America, but it may not run much longer. It was once three hours long, then two, now one. Lapides will turn 73 in November. He was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and had five stents put in his heart, and had eight feet removed from his small intestine. Still, he looks happy this morning. He smiles often, and his feet tap the floor with excitement as a very large young man approaches the table and sits down.

"A wonderful young man," Lapides said. "Barrett Jones from Alabama."

"Six, seven minutes," warns one of Jones's handlers, a serious man in a dark suit.

And so they talk like old friends for six or seven minutes. Their relationship is something of a coincidence. They're both from Memphis, and they both love the Memphis Grizzlies, and Lapides has often seen Jones and his family at the games. Jones made first-team All-American for the Crimson Tide last year as a junior, and now Lapides looks at him like a grandfather beholding his grandson.

The coach is around here somewhere. In a few minutes he will address the crowd upstairs. It will be a perfectly nice speech, and perfectly bland, featuring liberal use of the words enhance and maximize and implement and forefront and beneficial and outcome. Then the great Nick Saban, heir to the throne of Bear Bryant, will walk off the stage just as remote and unknowable as he was when he arrived.

But here they are, Lapides and Jones, just an old man and a young man, just talking. This will probably be the last SEC Media Days for George Lapides. There is not much point in coming anymore.

The dark-suited handler waves a finger in a circular motion, indicating that time is up.

George Lapides looks at Barrett Jones.

"Always good to see you," he said. "Say hello to your folks for me."