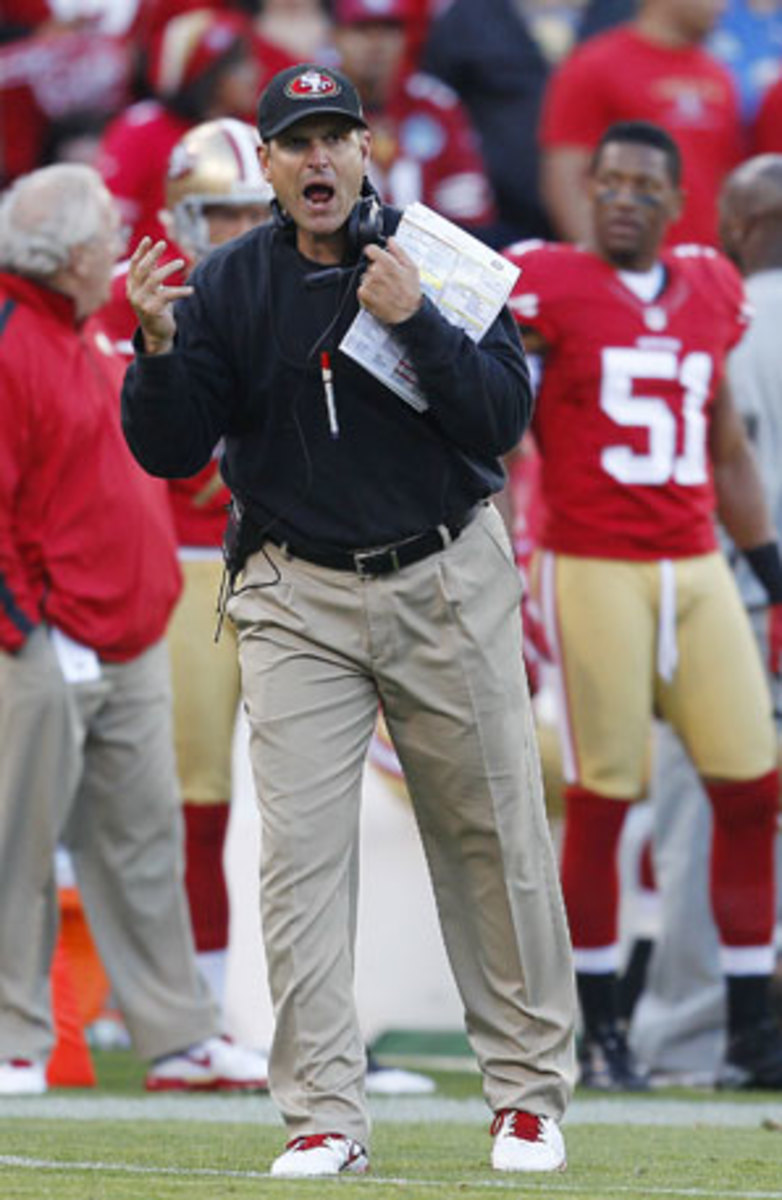

49ers coach Jim Harbaugh is Mr. Intensity -- all the time

One Saturday morning during the spring of 2011, a friend of mine named Ryan sat by a pool in Palo Alto, Calif., watching his two-year-old son flap around in the foot-deep kiddie area in that half-engaged way that fathers do. Though it was sunny and warm, only one other parent was present, a man with a baseball cap wedged low on his head who was feverishly texting on his phone. Nearby, the man's young daughter splashed about.

Ryan's son, who much like his father does not lack for energy, took hold of a small rubber toy and began chucking it to and fro. After a few throws, the boy turned, wound up and fired the toy directly at the little girl. It missed her head by less than an inch, whizzing by at great velocity. Sheepishly, Ryan prepared to warn his son about the perils of beaning other toddlers in the kiddie pool, but before he could, the man in the hat had jolted upright and turned toward Ryan, eyes blazing.

"That kid's got A HELL OF AN ARM!" the man announced. Then, looking at Ryan, he added: "You're either born with it or you're not."

And then Jim Harbaugh returned to hammering away at his phone

Depending on how you feel about Harbaugh, this anecdote either surprises you a little or not at all. If head coaches fall into various stereotypes -- the Intellectual, the Good ol' Boy, the Intimidator -- Harbaugh belongs in a category unto himself, half coach and half mascot. To watch him on the sideline during a game is to see a man who appears to be at all times on the verge of full-blown mania. Give most of us five shots of whiskey, a Red Bull and a high dose of Ritalin and I doubt we could approach Harbaugh's demonstrative intensity.

This, apparently, is how Harbaugh has been his whole life. According to my SI colleague Michael Rosenberg, when Harbaugh was young, his father, Jack, encouraged him to tackle every day with "an enthusiasm unknown to mankind" (he told the same thing to Jim's brother, John, who in the years since appears not to have taken the advice quite so literally). Jim was the type of boy who not only created his own basketball hoop out of a wire hanger in the basement and played imaginary games, but also kept stats and standings for those imaginary games. Whether he high-fived himself after made buckets is unknown.

The first time I saw Harbaugh coach was in Eugene, Ore., in 2008, when he was the coach at Stanford. At the time the Cardinal were still mediocre, and I was there with three friends, one of whom was a big Oregon Ducks fan. The idea was to tailgate with the Oregon faithful and experience the atmosphere. Nevertheless, by halftime three of us had all but stopped following the action on the field and were instead watching Harbaugh. He flailed his arms, sprinted down the sideline, bellowed at the referees and addressed his players like a full-contact revivalist preacher -- the entire game. It was the first, and only, time I've seen a coach head butt his punter.

As anyone who's watched the Niners recently knows, time has not mellowed Harbaugh. There is a clip of him from the first game of this season that is particularly defining: neck veins bulging, pen flying, spittle shooting from his mouth. It is one of many Harbaugh moments available for perusal on the web. There is the time last January when he prepared Alex Smith for a playoff game by ferociously pummeling his quarterback's torso; the moment in August when he appeared to be trying to scalp himself during a preseason game. And of course there's his infamous handshake/assault upon Lions coach Jim Schwartz.

Here in the Bay Area, where Harbaugh took a dormant franchise and revived it in one season, he is as revered as any athlete or coach since the era of Montana, Rice and Walsh. This is due in large part to his success -- a record of 16-5 as San Francisco's coach -- but also to his personality. After all, George Seifert, Tim Lincecum and Barry Bonds were all enormously successful, but none approached the game with Harbaugh's outward passion. (Similarly, Mike Singletary acted plenty intense but appeared to do so only for the sake of doing so; he neither won games nor won over his players).

Back in April, 49ers linebacker Patrick Willis described his coach in a radio interview as, "crazy," but "a good crazy." Said Willis: "He's the kind of crazy that there is not a player on that team that would not go to war with him. And when I say go to war with him I mean, he's crazy -- but most people would say, 'How could somebody be crazy but it's good?' He's crazy in that if he had to lay himself on the line to make sure that you'd live [he] would do that."

How could somebody be crazy but it's good? The answer depends on context, I suppose. Should professional football coaches be so intense that they act like madmen on the sideline, so focused that they scout toddlers in the wading pool? Do we want perspective from such men -- the acknowledgment that this is only a game, after all -- or do we want to live through them for a chunk of our Sunday afternoons, wrapped up and carried along in their tide of emotion?

With Harbaugh, there's no choice; he's all-in, all the time. Earlier this month, his youngest child, Jack Jr., was born. The boy weighed eight pounds and eight ounces. At that size and age, he could barely see, and was many months away from crawling. Still, his father was already sure of one thing. Addressing the media the next day, Harbaugh declared of his newborn, "He wants to win too."