George Blanda was man of miracles

Al Davis is sitting across from me at the long table in his black, black office. We are dwelling in a gloriously silver-and-black past. He is more than eager to revisit the era. Without my asking, he is riffing from the cellulite reels that are still playing in his brain, like a Roman general remembering his greatest battles.

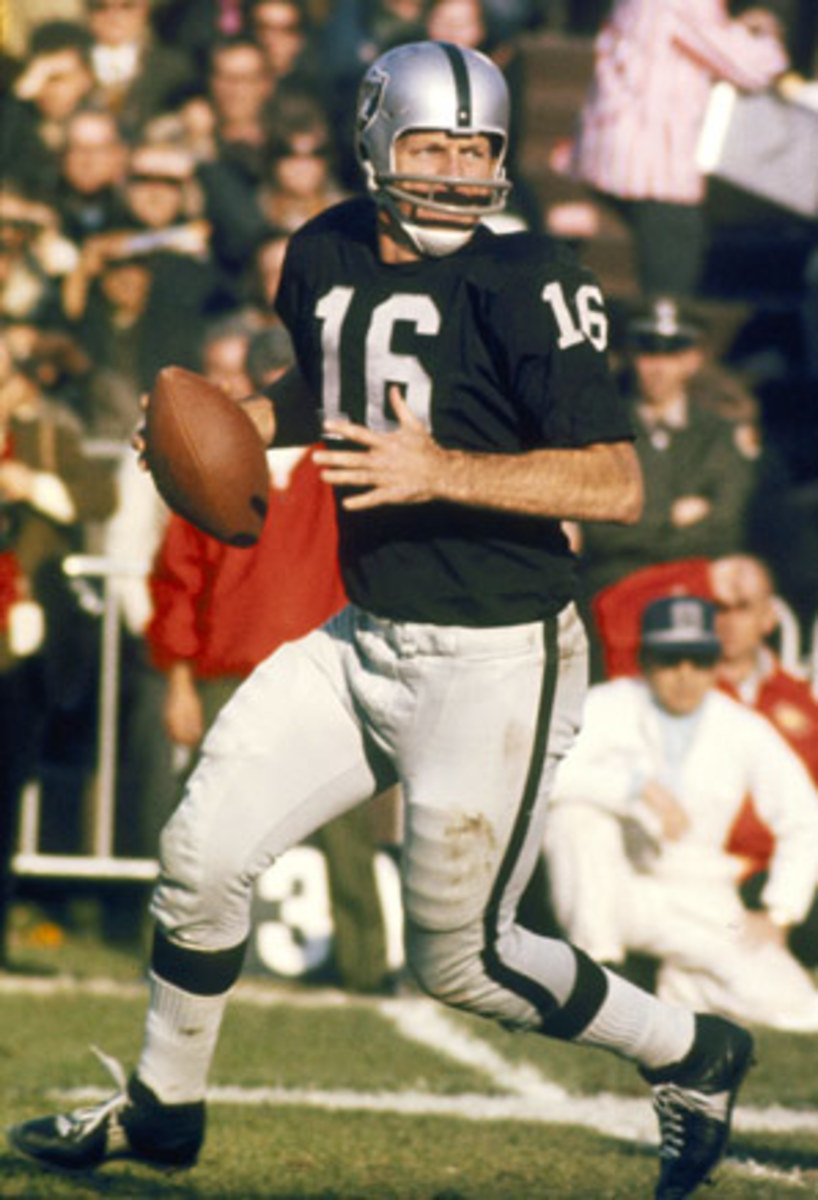

"The Heidi Game," he says. "The Immaculate Reception. The Sea of Hands. The Ghost to the Post. The Holy Roller. The miracles of Blanda."

Now, note: he could have said, "The Heidi Game, when Lamonica pulled off his miraculous fourth-quarter comeback." Or, "The Ghost to the Post, where Casper caught Stabler's pass in that miraculous six-quarter playoff win over the Colts." He didn't. The first name that jumped to Davis' head was George Blanda: the real man of miracles.

This conversation came to mind on Monday afternoon when the news broke that Blanda died at the age of 83 after a brief illness.

Technically, the Blanda miracles occurred in 1970, and numbered five. Blanda personally won five straight games that year for the Raiders, who reached the AFC Championship Game. The first miracle featured two late off-the-bench touchdown passes to Raymond Chester (who was 14 months old when Blanda played his first pro game), in an upset of the Steelers. The next four: a field goal to tie the hated Chiefs; a touchdown pass that tied a game against the Browns, and the field goal that won it; a touchdown pass to Fred Biletnikoff to beat the Broncos, and a late, winning field goal against the Chargers.

But the real miracle, of course, was that Blanda was 43 years old in 1970. The son of a coal miner born in Czechoslovakia, he played his first NFL game when Harry Truman was the president, The Lone Ranger premiered on TV and the most intriguing NFL rivalry in New York was between the New York Giants and the New York Bulldogs. In that season, Blanda, then with the Chicago Bears, helped his team beat the Chicago Cardinals. Twice.

But these are simple statistics, and, as history tells us, the truth lies not in the facts, but in the legend. And if you remember football as football, and not as entertainment, George Blanda was a mythic legend.

So flash forward to 1958, when the NFL caught hold with the nation, thanks to the historic overtime Giants-Colts championship game. Blanda, after 10 years in the NFL, quit the sport because Bears coach George Halas, a man who watched fights in Rush Street bars on Saturday nights and would sign the winners to Sunday's roster, had lost his faith in the Blanda's passing, and relegated him to kicking. The fledgling Houston Oilers of the AFL, in their first year, were more than happy to sign Blanda. In his first game in 1960, Blanda beat ... the Oakland Raiders, then led the Oilers to the AFL's first title.

There was ample reason for Davis to remember Blanda's name before all others in the Raider pantheon: Blanda was an emblem of the rebel AFL, of which Davis was commissioner for a few months in 1966, when, before the merger, Davis wanted no merger; he wanted to bring the NFL to its knees. For Davis, who has never put any faith in players who point to themselves, Blanda represented the men he had worshipped since childhood: football players.

Blanda wasn't boastful like Joe Namath, the first AFL --and pro football --entertainment superstar. Blanda was the sport's consummate icon: a man who reveled in the game itself, and was pissed off if he wasn't starting. Blanda was the old-world guy, with one foot back in the days of the Decatur Staleys, an athlete who would pass for the touchdown, kick the extra point, and then, if necessary kick the game-winning field goal. Blanda represented football. When the Oilers released him at the age of 40, Davis pounced.

To the Raiders, Blanda became an instant mentor. He was never beloved, and he never wanted to be. But people listened to him. And they revered him. When Blanda gave his old golf bag to Kenny Stabler, the gesture represented a beloved rite of passage.

Today, the players remember Blanda as a tough, sometimes surly competitor who had astounding confidence and was never afraid to speak his mind. If a pack of sportswriters interviewing Stabler spilled over into Blanda's locker space, he'd bite their heads off.

With apologies to Dylan Thomas, when the end came after 26 seasons, Blanda, characteristically, did not go gently into that good night. In 1976, Davis the businessman drafted a kicker from Germany named Fred Steinfort. In camp, contrary to rumors that Blanda and Steinfort never spoke during training camp, they actually did. Steinfort walked to Blanda's locker one day and said, "Hello, I'm Fred Steinfort."

"You didn't have to tell me," Blanda answered. "I knew who the f--- you were."

Blanda didn't play during the six-game exhibition season. And he wasn't reluctant to vent his frustration. "It's been embarrassing," Blanda told a writer from a lounge chair at the pool of the El Rancho Tropicana motel, the Raiders' wild and woolly summer-camp retreat. "It's like waiting to be beheaded. I'm like a cancer out on that field. The players treat me like I have leprosy. I have no animosity toward Al Davis or John Madden. I just don't care."

The words were hollow. He cared. Before the final preseason game against the Rams, Blanda was cut. He left camp during one of the final practices. Players came off the field to see a disarmingly empty locker.

"It's kind of sad," said Biletnikoff that day. "There should have been some way of having him leave that would give you a good feeling. There should have been something to bring a tear to your eye ... it's like the guy going to the electric chair."

"I was three years old when he started," said Stabler, about to lead the Raiders to their first Super Bowl. "I remember getting his autograph one time. As cold and hard as he was, I enjoyed being around him. He would tell you what he thought. If you liked him, fine. If you didn't like him, the hell with you. He had that certain quality a lot of people don't have. He was sort of like the Knute Rockne thing -- win one for the Gipper, work hard. Times have changed. Football isn't like that anymore."

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen's spin reflected the sentiments of the Raider Nation at large in his column a few days later: "Raider boss Al Davis' ticker has to be as hard as the 'Banker's Heart' sculpture outside the Bank of America headquarters," Caen wrote.

That 200-ton sculpture is made of granite. It will endure for a long, long time. Maybe back then, Al's heart was just as hard as Blanda's will to play. Today, Blanda's legacy lives on, lovingly, in the heart of Davis, now desperately searching for football players. If he's looking for Blandas, they no longer exist. But Al can't shake the memory of the man. And neither should we.