NFL and Players' Union at odds over validity of HGH test

The NFL Player's Association has confounded the NFL and science experts in recent weeks by debating the validity of an HGH test that has been widely stamped for a approval by independent scientists, leaving some of those involved in the meetings to suggest that union politics are obstructing the process of drug testing. On Friday, owners of all 32 NFL teams received notice from the league that the HGH test would not be in place for the start of the regular season, though that was the previously agreed upon goal of the NFL and the NFLPA.

In a letter to NFLPA lawyers obtained by SI.com, NFL lead counsel Jeffrey Pash wrote that "we have now almost certainly lost the opportunity to implement this testing by the start of the regular season, and would therefore request that you let us know at the earliest possible time whether there are any remaining issues."

Gerry Baumann, professor emeritus in medicine-endocrinology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and perhaps the world's foremost authority on human growth hormone, thought that any lingering scientific issues were answered in the NFL and NFLPA's meeting last month at World Anti-Doping Agency headquarters in Montreal, which he attended as an independent expert. "To my knowledge, in the scientific community there's very little disagreement about the [HGH] test," Baumann says. "From my perspective, it appears to be quite reliable and quite conservative in terms of it errs on the side of avoiding false positives."

The NFL and the Player's Union agreed in July to begin blood testing for HGH as part of the new collective bargaining agreement, but in recent weeks the union has taken a defensive stance regarding the testing. Until an agreement is reached, the NFL's usual drug testing will proceed without an HGH test.

Baumann, who agreed to speak about the meeting at WADA headquarters in general terms, has been studying and working with human growth hormone for 30 years. He is an expert in the use of growth hormone treatment in adults and has been at the forefront of a number of major human growth hormone-related breakthroughs, among them the first sequencing of the gene that codes for the body's growth hormone receptors. And he has no vested interest in either side. Baumann walked away from the Montreal meeting feeling that, at least among the scientists in the room, there were no outstanding issues about the validity of the HGH blood test. Baumann says that he was asked "very few questions" during the meeting and that "the Player's Association side didn't raise any questions."

David Howman, director general of WADA, got the same impression. "There was no suggestion of challenge to the science," says Howman. "There weren't any high degree science questions that came up with our scientists." Which is why Howman told The New York Times that the union's science team had "accepted the test's validity." That interpretation of the meeting earned him a public rebuke from union spokesman George Atallah who said that Howman "should not be so arrogant and presumptuous to speak on our behalf or on the behalf of anybody from our team." (View the WADA presentation here.)

The scientific team from the union included two scientists from Aegis labs in Nashville and Paul Scott, a lawyer with an undergraduate degree in chemistry and biology and head of Scott Analytics, an anti-doping services firm. When contacted, Scott was not allowed by the NFLPA's legal team to discuss the meeting. Maurice Suh, an attorney representing the NFLPA in the discussions, did not return a call seeking comment.

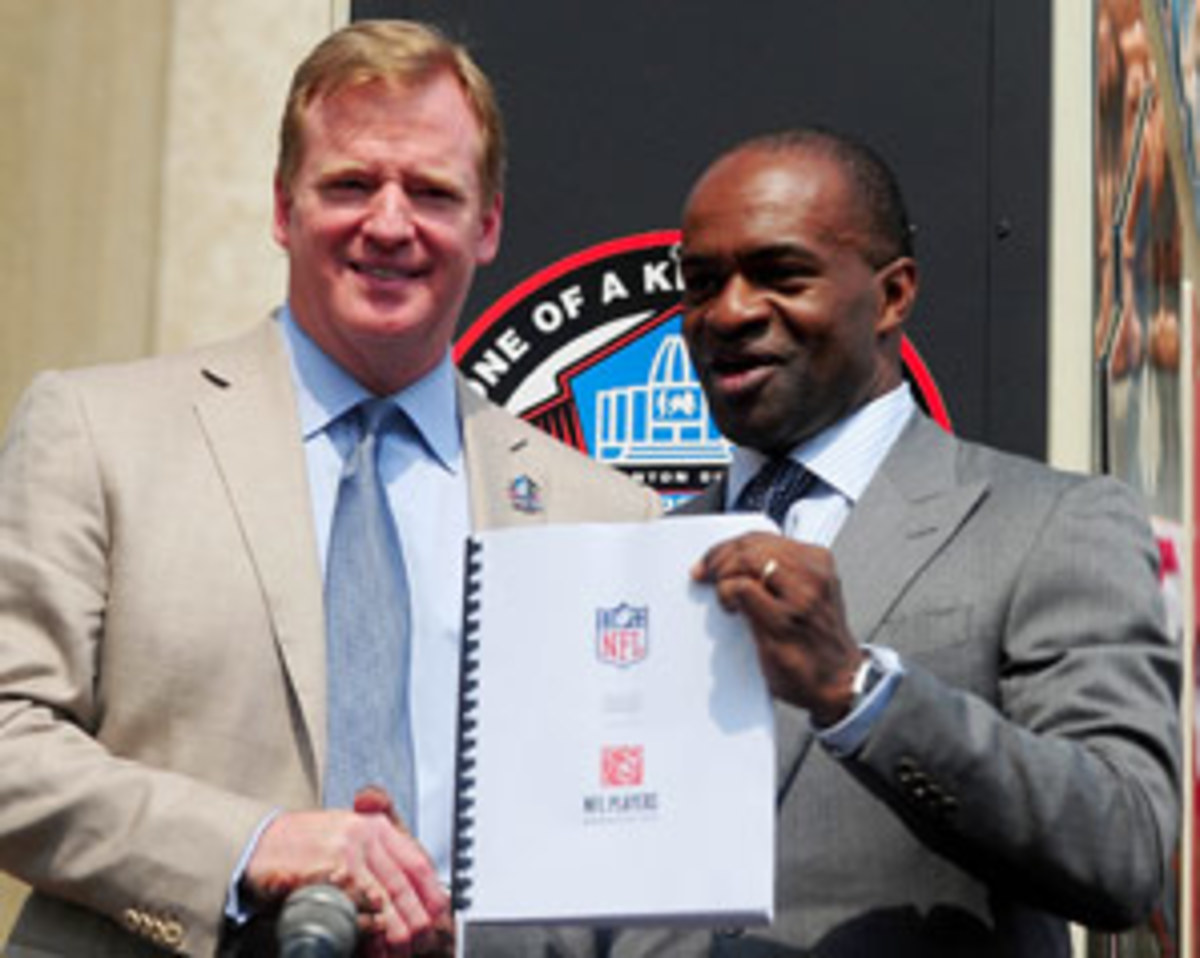

A conspicuous absence from the union's team at the meeting was NFLPA president DeMaurice Smith. According to three people who attended the meeting, Smith canceled the day before, to the dismay of commissioner Roger Goodell and NFL executives. (Atallah could not be reached by phone and another union spokesman did not return a message seeking comment.)

According to three people who are familiar with the HGH-testing discussions between the NFL and NFLPA, Smith has been under pressure to show some resistance on HGH testing because perception among some players is that the union hastily agreed to it in collective bargaining. As Steelers safety and player representative Ryan Clark put it: "I think people wanted to get a deal done so badly that it was overlooked ... In that sense, players kind of got screwed, for lack of a better word."

Says one source, who was not allowed to discuss the negotiations publicly, "This stand is to make DeMaurice Smith look tough where he caved originally." In a letter Goodell wrote to Smith on Tuesday, and which was obtained by SI.com, the commissioner notes that "Just prior to concluding the CBA, you raised for the first time your concerns regarding the reliability of the science underlying the tests." Regarding the meeting at WADA-headquarters, Goodell writes that he has "even greater comfort with the science underlying the testing."

The only significant critical questions about the HGH test at the meeting in Montreal, according to people who were present, were from Suh, the attorney who was brought in to work for the union on the matter. Suh is best known in the sports world for his tooth-and-nail defenses of athletes caught doping, most notably cyclist Floyd Landis, who was stripped of his Tour de France title and later admitted doping. Suh was part of the Landis legal group that was ordered by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) to pay $100,000 in legal fees to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency for disruptive tactics, the first and only defense team to suffer such a penalty before CAS, according to Michael Straubel, an attorney who has represented athletes before CAS and heads the Valparaiso University sports law clinic.

According to multiple sources familiar with the union representatives' discussions of the test, two issues that have been discussed among the union's science team are: the limited detection window of the test, and the one in 10,000 chance of a false positive. As far as the detection window, it is true that a football player who injects HGH may get away with it even if he is tested 36 hours later, as the testing window is probably two days at the very outside, which is longer than the window for some administration methods of testosterone and EPO.

"The only claim I can see is that the window for detecting HGH is narrow. Fair enough," says Christiane Ayotte, the director of the WADA-accredited lab in Montreal. "If we were only to test for substances that could be detected for [many months] later, then we would have only one test, for Nandrolone."

In a simplistic anti-doping nutshell, here's how the HGH test works: HGH comes in several different "isoforms" in the body. The isoform that comprises the majority of human growth hormone weighs 22 kilodaltons, and another form that makes up a smaller portion weighs 20 kilodaltons. These isoforms are produced naturally in a particular ratio, with the 20 kilodalton isoform comprising 5-10% of the human growth hormone in the body. Synthetic HGH comes only in the 22-kilodalton variety, such that injecting it upsets the natural ratio, and that's what the test looks for, an unnatural isoform ratio. Up until last year, the detection window was such that an athlete could have had HGH with his Cornflakes in the morning and not broken a sweat when tested at lunch.

At the start of the Vancouver Winter Olympics in '10, Ayotte said that the HGH test was so unlikely to produce a positive that "We rely on the fact that if you take growth hormone, you will certainly take something else that is easier to detect." But by early last year, anti-doping scientists had compiled enough data on the natural ratio of isoforms in the body that the trigger for a positive test went from a ratio that was over six-times normal to about three-times normal. Finally, positive tests began to roll in. Ayotte was present at the meeting last year where Major League Baseball discussed HGH testing with WADA, and the test was instituted in the minors, where it needn't be collectively bargained, shortly thereafter. There have now been eight positive tests worldwide, and in the four that have been fully adjudicated (that is, they are not under review or pending appeal), the athletes have admitted doping, most recently Mike Jacobs, a first basemen in the Colorado Rockies minor league system.

The only scientist who has publicly criticized the test is Don Catlin, founder of the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory. Regarding the potential for false positives, Catlin told the New York Daily News that "We understand that people are sometimes put in jail or even put to death because of mistakes. One in 10,000 - is that acceptable? It's not if you are that one person, but it's acceptable to most of us. But if it is 1 in 10, then you know we are not there yet." The false positive rate of the test is in fact, not 1 in 10, but 1 in 10,000. And Catlin might have a bone to pick with the blood test for HGH. As SI reported previously, the NFL was giving Catlin's nonprofit Anti-Doping Research up to $200,000 dollars a year to develop a urine test for HGH, but ended their funding a year prematurely because no progress was being made. "[Catlin] has done sterling work in the past, and I'm full of praise for the work he has done," Howman says. "But you can't work on memories. He did have a [financial deal with the NFL], and it was terminated and he probably regrets that...Therefore he's taken to speaking for the other side."

All medical and all anti-doping tests, like those for EPO and HCG, have the potential for a false positive. "You have to weigh the evidence," Baumann says. "From a scientific perspective, it seems very robust and conservative to me. I don't think this is any different from any other tests in the anti-doping world, and the consensus in the WADA meeting was that it's no different. [As anti-doping tests go], I think this is about as good as it gets."