Is Kyle Busch the biggest troublemaker in NASCAR history?

Busch is dynamite on the racetrack with an incredible record: 30 wins in Trucks, 51 in Nationwide and 23 in Sprint Cup. But like a wild mustang, Busch is fast and furious and extremely hard to tame. This year alone, Busch has sparred with Kevin Harvick, Richard Childress, Elliott Sadler and Ron Hornaday Jr. The latter incident, which cost Hornaday a shot at the Camping World Series title, earned Busch the ire of NASCAR, which parked him for the remainder of the race and the following Nationwide and Sprint Cup races at Texas. The suspension mathematically eliminated Busch from this year's Chase for the Championship.

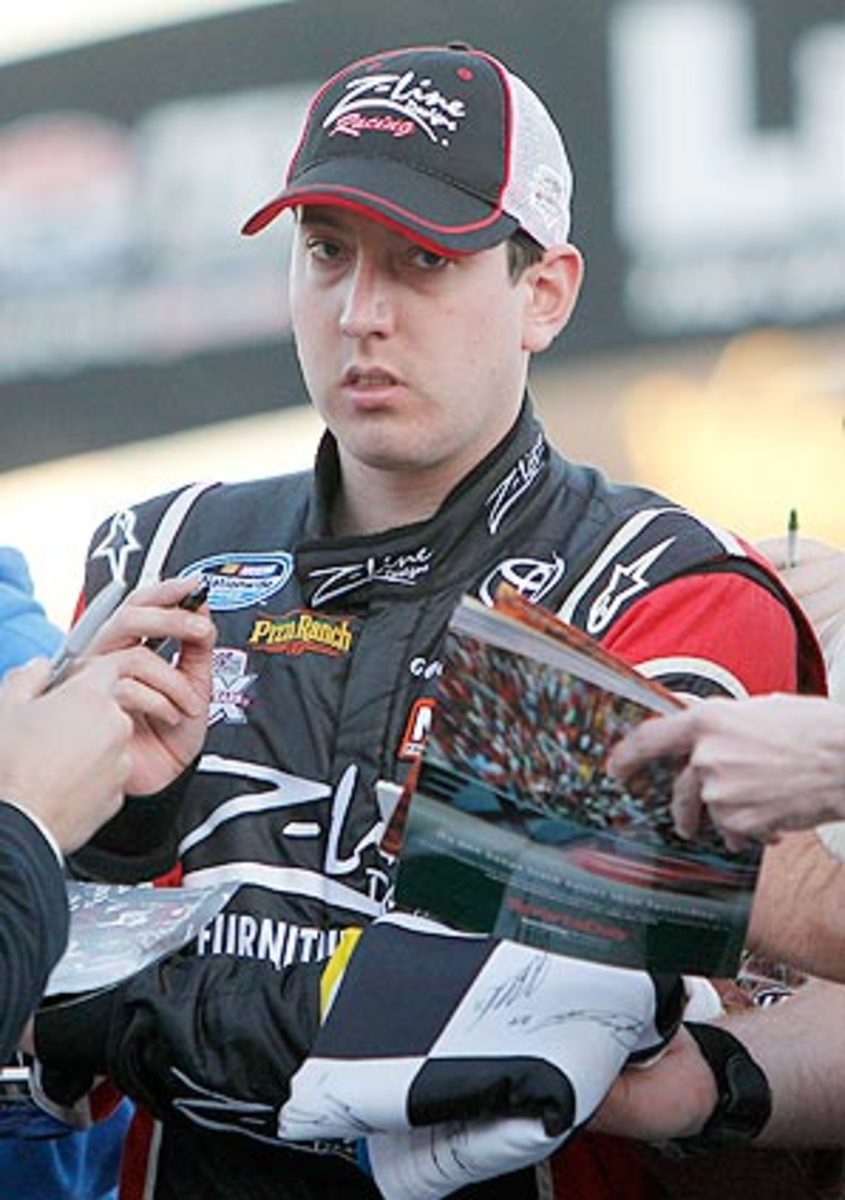

Supremely confident, the 26-year-old driver is among the greatest to ever climb behind the wheel of a race car. He is already the all-time victory leader in the Nationwide Series. To watch Busch at his best is a chance to marvel at a rare talent. There are times when it seems the only person who can stop Kyle Busch is himself. But lately that has been the problem.

Busch isn't the first successful driver with a mean streak. Dale Earnhardt is considered by many to be the greatest driver in NASCAR history. The seven-time Cup champion won 76 races in his career but was just as famous for a hard-nosed driving style that earned him the nickname "The Intimidator." Earnhardt wasn't afraid to put another driver into the wall and was willing to settle the score himself in an era in which NASCAR was a sport where only the bravest of the brave climbed behind the wheel of a stock car.

Earnhardt struck fear into the hearts of his competitors. From wrecking Darrell Waltrip on purpose at Richmond in 1986 to his infamous "I-didn't-mean-to-wreck-him; I-just-meant-to-rattle-his-cage" crash with Terry Labonte at Bristol in 1999, Earnhardt used fear and intimidation as key tactics of his racing arsenal.

Waltrip was a bit of a troublemaker himself, but his mouth got him into trouble more than any dirty driving. Waltrip was a master of psychological warfare with his rivals, and his main combatants were Bobby Allison, Richard Petty and even Earnhardt. His mouth was so active it earned him the nickname "Jaws."

While Richard Petty is one of the most beloved and revered drivers in the history of the NASCAR his father Lee was one of the most reviled. The Petty Patriarch was a hard-driving man who once protested a victory by his son so that Lee could be declared the winner.

Jimmy Spencer's nickname was "Mr. Excitement" because he didn't mind putting a fender into another driver or pitching them into the wall if it meant gaining an advantage. His favorite target was Kyle's older brother, Kurt. The two were involved in many a battle, and the hard feelings boiled over at Michigan in Aug. 2003, when Spencer reached through Busch's window and punched Busch several times in the face. Both drivers would meet with NASCAR officials after the incident, and even the Lenawee County (Mich.) Sheriff's Department got involved, but no charges were ever filed. Nevertheless, the incident between two of NASCAR's best troublemakers has taken on folklore status.

In a rare move, NASCAR parked Kevin Harvick for a Cup race as punishment for his actions in a Truck Series race in 2002. Harvick, angry at Greg Biffle, drove his wounded truck into the garage area in an attempt to run over his rival. NASCAR parked Harvick for the following day's Cup race, citing his "rough driving."

Cale Yarborough may have been short, but he was built like a sparkplug and was never afraid to rough it up on or off the racetrack. While fighting for the win on the final lap of the 1979 Daytona 500, Yarborough and Donnie Allison repeatedly slammed into each other, allowing Richard Petty to drive to his sixth career Daytona 500 victory. Afterward, while Petty was on his cool-down lap, Yarborough started a fight with Allison. Older brother Bobby jumped into the action and the images of Yarborough and Bobby Allison in a fight on the apron of Turn 3 helped launch the sport into mainstream recognition because it was the first time the race had been shown live, flag-to-flag, by CBS television.

With much of the eastern and midwestern United States snowed in by the Great Blizzard of 1979, the action of a few troublemakers helped popularize NASCAR to the masses.

Curtis Turner may have been one of NASCAR's ultimate troublemakers, but the rough-edged, hard-drinking and hard-partying driver was once banned for life for a relatively innocuous transgression: trying to organize the drivers as part of a union in 1961. NASCAR founder Bill France kicked Turner out of the sport, although the ban would eventually be lifted in 1965. Turner was later killed in an airplane crash near Punxsutawney, Pa. on Oct. 4, 1970.

Back in those days NASCAR was a sport for the oddballs, malcontents and troublemakers. It was considered a sport from the other side of the tracks, and those antics appealed to a crowd of fans who toiled in thankless jobs in the textile mills of the Southeast. Fines by NASCAR were rare and even then the penalties were nominal by today's standards.

Since the era of Earnhardt, NASCAR has attempted to become a much more sophisticated sport. There are hundreds of millions of dollars in corporate sponsorship supporting this series and that meant in many ways the sport had to clean up its act. It wanted its drivers to be clean cut and look good in Hugo Boss and Armani suits to get away from the image of a bunch of hell raisers.

But over time, its core group of fans became disillusioned by a sport that had been toned down. The personalities were missing and the racing had become mundane. NASCAR needed to go back to the formula that had worked so well in the first place and the solution was a combination of heroes and drivers who weren't afraid to wear the black hat and weren't afraid to settle the scores among themselves.

Kyle Busch not only fit both roles; he embraced them -- perhaps too well.

NASCAR fined Busch $50,000 for his latest transgression and put him on probation until Dec. 31 for violating Section 12-1 -- otherwise known as "actions detrimental to stock car racing." His main sponsor, M&M's, also penalized him, opting to pull its decals off his Toyota for the final two races of the season.

It's another indication that the sport hasn't changed as much as society has changed. A few decades earlier drivers such as Busch would have been hailed and revered by the hard-core, rough-cut group of NASCAR fans, who enjoyed watching a good fistfight after a race as much as the race itself.

In today's society a person can lose his or her job by hurting someone's feelings.

Busch still has tremendous appeal to a new segment of race fans. If he can control his impulsive behavior on the racetrack and think before taking action, this troublemaker can reform himself into a champion.

But a look back at NASCAR's raucous history shows that when it comes to getting into trouble, Kyle Busch is only the latest in a very long line of malcontents who have helped create a very colorful backdrop to this rough and tumble sport.